The Semiotics of Visible Face Make-Up: the Masks Women Wear

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NC-NY-Pricing-And-Details-2-53Hl

Congratulations on your engagement and thank you for your interest in Nancy Caroline Bridal Beauty. With 20 years experience in bridal hair and makeup, Nancy’s team of artists can create any style you’ve dreamed of for your special day. Our expertise in weddings and photoshoots will provide you with a hair and makeup style that will hold all day and night long and photograph perfectly. Please read on for our pricing information and booking details. Investment Hairstyling Nancy Associate Bride Hairstyling $400 $250 Formal Hairstyling (bridesmaids, mothers, guests) $150 $150 Short Hair Blowdry (above the chin only) $100 $100 Flower Girl Hairstyling $50 $50 Bridal Hair Preview - In Studio $150 $135 Extension Placement/Styling $20 $20 (no charge for extension placement if purchased from NCBB) Mens hair styling (neck/ear trim, brows, pomade styling) $50 $50 Boys hair styling (neck trim, pomade styling) $25 $25 Makeup Bridal Makeup Application $400 $250 Includes airbrush foundation, individual lashes, and full sized lipstick to keep Makeup Application (bridesmaids, mothers, guests) $150 $150 Includes airbrush foundation and complementary lashes Bridal Makeup Preview -In Studio $150 $135 Tattoo/Scar/Bruise Covering *starting at $80 $80 Mens Makeup $50 $50 Minimum in Wedding Day Services (Friday thru Sunday) $1600 $600 Wedding Day Extended Beauty $350/hr $150/hr We will stay to ensure your hair and makeup look is refreshed for your grand reception entrance. Hourly rate begins once the last person from your party is completed for photos. Early Weddings (ready by 10:30am or earlier) fee $450 $450 Holiday Fee $500 $300 Holidays include - Friday thru Monday of Labor Day and Memorial Day weekends, Thanksgiving, Christmas Eve and Day, New Year’s Eve and Day, Easter, and Fourth of July How to Book First - Read over this entire document, most of the answers to your questions are right here. -

SAS Flightshop Great Offers on Board

SAS Flightshop Great offers on board. Valid 8 September 2006 –7February 2007 www.georgjensen.com Best deals on board Welcome on board this SAS flight. Wherever you are flying to, you are in for some great deals, up to 20% cheaper than downtown! We have made our selection from some of the world’s top suppliers of Scandinavian design, perfumes, confectionery, jewelry, toys and fashion, some of them only available on board SAS. We can offer you some great savings on many purchases. But don’t wait around – due to the space on is board, most items are only available in a limited number. Hurry – treat yourself and your family and friends to some great gifts now! there anything more Selected Favorites! seductive See page 14–15 than purity? 7 For More Style 25 Assortment outside the EU 22 For the Kids 4 At Home & Away 24 For Good Taste 20 For Him Please note – sales will only take place on board flights longer than: 1h 45 min CELEBRATION OF THE HEART from Copenhagen Each year, Georg Jensen selects one designer to interpret the heart – the world’s oldest symbol of love – as the ANNUAL ARTIST HEART COLLECTION 2006 ARTIST HEART 1h 35 min from Stockholm and Oslo Pendant in sterling silver. 12 For Her Design Karim Rashid. 4 At Home & Away Save up to 20% compared to down-town retail prices Save up to 20% compared to down-town retail prices At Home & Away 5 606 Scorpio Mini Travel Speakers New! Never before has such small speakers produced such superb sound quality! Even the most demanding listener will appreciate the slim and portable design, ideal for trave- ling. -

Sociology of Fashion: Order and Change

SO39CH09-Aspers ARI 24 June 2013 14:3 Sociology of Fashion: Order and Change Patrik Aspers1,2 and Fred´ eric´ Godart3 1Department of Sociology, Uppsala University, SE-751 26 Uppsala, Sweden 2Swedish School of Textiles, University of Bora˚s, SE-501 90 Bora˚s, Sweden; email: [email protected] 3Organisational Behaviour Department, INSEAD, 77305 Fontainebleau, France; email: [email protected] Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2013. 39:171–92 Keywords First published online as a Review in Advance on diffusion, distinction, identity, imitation, structure May 22, 2013 The Annual Review of Sociology is online at Abstract http://soc.annualreviews.org In this article, we synthesize and analyze sociological understanding Access provided by Emory University on 10/05/16. For personal use only. This article’s doi: Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2013.39:171-192. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org of fashion, with the main part of the review devoted to classical and 10.1146/annurev-soc-071811-145526 recent sociological work. To further the development of this largely Copyright c 2013 by Annual Reviews. interdisciplinary field, we also highlight the key points of research in All rights reserved other disciplines. We define fashion as an unplanned process of re- current change against a backdrop of order in the public realm. We clarify this definition after tracing fashion’s origins and history. As a social phenomenon, fashion has been culturally and economically sig- nificant since the dawn of Modernity and has increased in importance with the emergence of mass markets, in terms of both production and consumption. Most research on this topic is concerned with dress, but we argue that there are no domain restrictions that should constrain fashion theories. -

Cosmetics, Fast Fashion to Gain from Luxury Decline

MACAU PASS TO JOIN UMAC STUDENTS PROTEST 50 CITIES IN SMART DURING UNION INAUGURATION GREAT FIGO CARD NETWORK 2 students held a sign calling on the IN THE RACE Macau Pass is expected union to take a tough stance and FOR FIFA’S to join the nationwide pressure uni leaders to come clean TOP POST integrated City Union card scheme this July on alleged political oppression P3 P7 P19 THU.29 Jan 2015 T. 16º/ 21º C H. 70/ 95% Blackberry email service powered by CTM MOP 5.00 2239 N.º HKD 7.50 FOUNDER & PUBLISHER Kowie Geldenhuys EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Paulo Coutinho “ THE TIMES THEY ARE A-CHANGIN’ ” WORLD BRIEFS Cosmetics, fast fashion to AP PHOTO gain from luxury decline P2 JLL FORECAST NORTH KOREAN leader Kim Jong Un will make his first foreign trip since coming to power three years ago to attend AP PHOTO celebrations for the 70th anniversary of Russia’s victory in World War II, the Interfax news agency reported. Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov confirmed to Interfax that the Korean leader would attend the event to be held on May 9. Chinese President Xi Jinping and about 20 foreign leaders are also expected to attend, the Itar-Tass news agency reported on Jan. 21. CHINA A man admitted yesterday that he set a fire that spread through a bus in eastern China and injured 33, entering his plea from a hospital bed wheeled into a courtroom because of his own injuries in the blaze, a court said. Bao Laixu said he started the fire last July in the city of Hangzhou to take revenge against society and because he wanted to end his own life after a relapse of tuberculosis, the Hangzhou Intermediate People’s Court said on its microblog. -

In Japan and the US and Portrayals of Women's Roles in Makeup

Megumi Taruta (1M151151-3) Graduation Thesis Definition of “Beauty” in Japan and the US and Portrayals of women’s roles in Makeup Video Advertisements of America and Japan ~Comparative Case Study on Cosmetic Brands: Maybelline New York and Maquillage ~ Graduation Thesis for Bachelors of Arts Degree Waseda University, School of International Liberal Studies, 2019 Megumi Taruta (1M151151-3) Professor Graham Law Media History/ Media Studies Seminar July 2019 1 Megumi Taruta (1M151151-3) Graduation Thesis Abstract This paper is written in order to achieve two aims: 1) find out the extent to which perceptions of beauty is similar in contemporary Japan and the US and 2) discover how the portrayals of women regarding their roles and lifestyles in recent beauty advertisements (within the last two decades) differ depending on different countries. It is a comparative case study on cosmetic brands using one brand for each country- Maybelline New York (the U.S) and Maquillage (Japan). The paper starts off with introducing the two brands by providing the history and the background information of each brand. Company information of the owners of the brands (L’Oréal and Shiseido) is also included. In addition, an overview of current makeup market in the US and Japan is also written as extra background information. The two brands are chosen due to many similarities making it a fair comparison. They are similar in terms of price, the target market and the fact that they are both owned by global beauty companies. In terms of definition of beauty, the analysis is divided into body parts: skin, lips and eyes- specifically, eyeshadow for the eyes. -

People's Democratic Republic of Algeria Ministry of Higher Education

People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research University Abd El Hamid Ibn Badis Faculty of Foreign Languages Department of English Master in Literature and Interdisciplinary Approaches The US Beauty Industry and the Other Face of Racism towards the 21st Century African -American Women Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Master in Literature and Interdisciplinary Approaches Submitted By: Reguig Khadidja Board of Examiners: Chairperson: Ms. Bellel Hanane Supervisor: Mr. Teguia Cherif Examiner: Mrs. Adnani Rajaa 2018-2019 Dedication It is my genuine gratefulness and warmest regard that I dedicate this work to my beloved people who have meant and continue to mean so much to me. Although some of them are no longer in this world, their memories will always stay engraved in my heart. First and foremost, to my dear late grandmother Fatma who taught me kindness. To my family: my parents, my brothers and sisters for believing in me and for their unceasing encouragements and support. I would like to dedicate my work to my friends from secondary school days: Sarra and Omar. Unfortunately, I cannot mention everyone by name, it would take a lifetime. Just make sure you all count so much to me. Without your prayers, benedictions, sincere love and help, I would have never completed this dissertation. i Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor Mr. Teguia Cherif for his continuous support, patience, motivation, and immense knowledge. His guidance helped me all the time of research and writing of this dissertation. -

Penilaian Saham Pt. Alliance Cosmetics Per 31 Desember 2020

Graha STH Jl. Mandala Raya No. 20, Jakarta 11440 Tel : 021 – 563 7373 (Hunting) Fax : 021 – 563 6404 Email : [email protected] [email protected] Izin Usaha KJPP : No. 2.08.0007 Bidang Jasa : Penilaian Properti & Bisnis Wilayah Kerja : Indonesia PENILAIAN SAHAM PT. ALLIANCE COSMETICS PER 31 DESEMBER 2020 Professional Services in Valuation and Financial Consultancy Graha STH Jl. Mandala Raya No. 20, Jakarta 11440 Tel : 021 – 563 7373 (Hunting) Fax : 021 – 563 6404 Email : [email protected] [email protected] Izin Usaha KJPP : No. 2.08.0007 Jakarta, 8 Juni 2021 Bidang Jasa : Penilaian Properti & Bisnis Wilayah Kerja : Indonesia Direksi PT Mandom Indonesia Tbk. Wisma 46 Kota BNI Lantai 7 Suite 7.01 Jl. Jend. Sudirman Kav. 1, Karet Tengsin, Jakarta 10220 Dengan hormat, Ref. : File No. 00044/2.0007-00/BS/04/0027/1/VI/2021 Penilaian Saham PT Alliance Cosmetics Menindak lanjuti Surat Perjanjian Kerja No. STH-039/PR.012/SG/I/2021, kami sebagai Kantor Jasa Penilai Publik resmi berdasarkan Izin Usaha Kantor Penilai Publik No.2.08.0007 dan Surat Izin Penilai Publik No.: PB-1.08.00027 yang dikeluarkan oleh Menteri Keuangan Republik Indonesia serta Surat Tanda Terdaftar Profesi Penunjang Pasar Modal STTD PPPM-OJK No.: STTD.PPB-38/PM.223/2019 yang dikeluarkan oleh Otoritas Jasa Keuangan (“OJK”), telah melakukan revisi terhadap laporan penilaian kami atas Nilai Pasar saham PT Alliance Cosmetics (“PTA”) dengan File No. 00041/2.0007-00/BS/04/0027/1/IV/2021 yang kami lakukan per tanggal 31 Desember 2020, sehubungan dengan adanya perubahan dan atau tambahan informasi atas Rencana Transaksi PT Mandom Indonesia Tbk. -

UNIVERZITA KARLOVA V PRAZE Semiotics and Fashion Studies

UNIVERZITA KARLOVA V PRAZE FAKULTA HUMANITNÍCH STUDIÍ Katedra elektronicke kultury a semiotiky Mgr. Daria Mikerina Semiotics and Fashion Studies: Limits and possibilities of a systemic approach to contemporary fashion Diplomová práce Vedoucí práce: doc. Mgr. Benedetta Zaccarello, Ph.D. et Ph.D. Praha 2016 Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem práci vypracoval/a samostatně. Všechny použite prameny a literatura byly řádně citovány. Práce nebyla využita k získání jineho nebo stejneho titulu. V Praze dne 08. 1. 2016 Mgr. Daria Mikerina …............................................ Acknowledgement I would like to thank my supervisor, doc. Mgr. Benedetta Zaccarello, Ph.D. et Ph.D. for guidance, encouragement, advice and support. I would also like to thank my friend J. Christian Odehnal for proofreading the thesis and continued support. Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: The concept of system in semiotics. Fashion as an open and dynamic system ….................................................................. 7 Linguistic system according to Saussure ● The role of the system in structuralism ● Cultural systems ● The place of language in non-linguistic systems ● Typology of systems in semiotics ● Systems and codes ● Fashion as open and dynamic system ● The critique of structure and system Chapter 2: How fashion is produced. The phenomenon of named signifieds in Barthes' Fashion System …....................... 15 Part I. Finding a new methodology. “Fashion is nothing except what it is said to be” ….......................................................... 15 Sociology of fashion and semiology of fashion ● Dress and dressing. Fashion as “a langue without parole” ● Clothing and fashion ● Is dress an index? ● Semiology and its relation to other ways of analysis of fashion ●“To accept a simplification in all its openness” ● To describe fashion as a system we need to modify it ● Research object ● The necessity of “translation” Part II. -

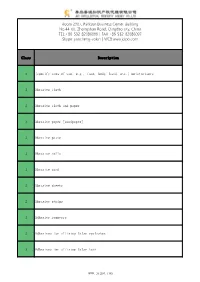

Class Description 3 {Specify Area of Use, E.G., Face, Body, Hand, Etc

Room 2907, Parkson Business Center Building No.44-60, Zhongshan Road, Qingdao city, China TEL:+86-532-82086099|FAX:+86-532-82086097 Skype: jiancheng-cokin|WEB:www.jcipo.com Class Description 3 {specify area of use, e.g., face, body, hand, etc.} moisturizers 3 Abrasive cloth 3 Abrasive cloth and paper 3 Abrasive paper [sandpaper] 3 Abrasive paste 3 Abrasive rolls 3 Abrasive sand 3 Abrasive sheets 3 Abrasive strips 3 Adhesive removers 3 Adhesives for affixing false eyelashes 3 Adhesives for affixing false hair www.jcipo.com 3 Adhesives for affixing false eyebrows 3 Adhesives for artificial nails 3 Adhesives for attaching artificial fingernails and/or eyelashes 3 Adhesives for cosmetic use 3 Adhesives for false eyelashes, hair and nails Aerosol spray for cleaning condenser coils of air filters for air conditioning, 3 heating and air filtration units 3 After shave lotions 3 After sun creams 3 After sun moisturisers 3 Aftershave 3 Aftershave cologne 3 Aftershave moisturising cream 3 Aftershave preparations 3 After-shave 3 After-shave balms www.jcipo.com 3 After-shave creams 3 After-shave emulsions 3 After-shave gel 3 After-shave liquid 3 After-shave lotions 3 After-sun gels [cosmetics] 3 After-sun lotions 3 After-sun milks [cosmetics] 3 After-sun oils [cosmetics] 3 Age retardant gel 3 Age retardant lotion 3 Age spot reducing creams 3 Air fragrancing preparations 3 Alcohol for cleaning purposes 3 All purpose cleaning preparations www.jcipo.com 3 All purpose cleaning preparation with deodorizing properties 3 All purpose cotton swabs for personal -

Feminist Media Studies

UPPSALA UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF INFORMATION SCIENCE DIVISION OF MEDIA AND COMMUNICATION MASTER THESIS IN MEDIA AND COMMUNICATION STUDIES D-LEVEL, SPRING TERM 2007 FASHIONING THE FEMALE An Analysis of the “Fashionable Woman” in ELLE Magazine – Now and Then Author: Heidi Marie Nömm Tutor: Ylva Ekström ABSTRACT Title: FASHIONING THE FEMALE - An Analysis of the “Fashionable Woman” in ELLE Magazine - Now and Then Number of pages: 57 (including diagrams and figures, excluding enclosures) Author: Heidi Marie Nömm Tutor: Ylva Ekström Course: Media and Communication Studies D Level, Master Thesis Period: Spring term 2007 University: Uppsala University Division of Media and Communication Department of Information Science Purpose/Aim: The purpose of this master thesis is to investigate how fashion can function as a communication channel and how the modern Swedish woman is represented in ELLE magazine within two different fashion decades, in 1992 and 2007. Material: Swedish ELLE magazines No. 1-4 1992 and No. 1-4 2007. Method: A complementary combination of quantitative content analysis, semiotics and critical discourse analysis. Main results: A number of differences, as well as similarities can be recognised between the fashions of 1992 and 2007. The latter one is characterised by women looking serious, sometimes even austere while 1992 shows often happy women. The fashion styles are much more casual, colourful and more accessorised by jewellery etc. in 1992, while the clothing in 2007 is often tight, body hugging and reveals more skin. Concerning ethnicity, 2007 only shows white women, often very feminine and wearing mostly dresses and rarely pants, whereas 1992 is characterised by ELLE’s effort to show a more multicultural and diversified picture of the female. -

MPC MAJOR RESEARCH PAPER Why My Dad Is Not Dangerously

MPC MAJOR RESEARCH PAPER Why My Dad Is Not Dangerously Regular: Normcore and The Communication of Identity Brittney Brightman Professor Jessica Mudry The Major Research Paper is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Professional Communication Ryerson University Toronto, Ontario, Canada August 2015 AUTHOR'S DECLARATION I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this Major Research Paper and the accompanying Research Poster. This is a true copy of the MRP and the research poster, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this major research paper and/or poster to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this MRP and/or poster by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my MRP and/or my MRP research poster may be made electronically available to the public. ii ABSTRACT Background: Using descriptors such as “dangerously regular”, K-Hole’s style movement has been making waves in the fashion industry for its unique, yet familiar Jerry Seinfeld-esque style. This de rigueur ensemble of the 90’s has been revamped into today’s Normcore. A Normcore enthusiast is someone who has mastered the coolness and individuality of fashion and is now interested in blending in. Purpose: The goal of this research was to understand the cultural relevance of the fashion trend Normcore, its subsequent relationship to fashion and identity, as well as what it reveals about contemporary Western culture and the communicative abilities of fashion. -

Elizabeth Arden Ingredients

Elizabeth Arden Ingredients Water, Sodium Cocoyl Isethionate, Glycerin, PEG 120 Methyl Glucose Dioleate, Elizabeth Arden 2 in 1 Myristic Acid, Sodium Myrisoyl Sarcosinate, Rosemary Extract, Sage Extract, Cleanser for All Skin Types - Witch Hazel Distillate, Propylene Glycol, Sodium Myristate, Trihydroxystearin, Unboxed 5oz/150ml-ARD-02 Hydroxypropyl, Methylce Glycerin - Intensely moisturizes the skin by attracting water to the surface of the skin. Shea Butter - Triglycerides in the shea butter helps to replace some of the fatty acids that are deficient in the skin. Skin is smoother, less flaky and more moisturized. Sodium Hyaluronate and Imperete Cylindrica Extract Provides deep moisturization. Water/Aqua/Eau, Butyrospermum Parkii (Shea Butter), Cetearyl Glucoside, Glycerin, Myristyl Myristate, Cyclopentasiloxane, Butylene Glycol, Cetyl Alcohol, Octyldodecyl Myristate, Cetearyl Alcohol, Cetyl Palmitate, Dimethicone, Isostearyl Neopentanoate, Imperata Cylindrica Root Extract, Sodium Hyaluronate, Tocopheryl Acetate, Cetyl Myristate, Cetyl Elizabeth Arden 8 Hour Cream Stearate, Cholesterol, Peg-8, Acrylates/C10-30 Alkyl Acrylate Crosspolymer, Intensive Moisturizing Body Carbomer, Polymethyl Methacrylate, Xanthan Gum, Sodium Hydroxide, Bht, Treatment Tube - Boxed Disodium Edta, Cyclohexasiloxane, Parfum/Fragrance, Citral, Citronellol, 6.8oz/200ml-ARD-03 Geraniol, Limonene, Linalool, Phenoxyethanol Butylene Glycol, Dimethicone: Powerful humectants that help to keep the skin moist and hydrated by attracting water to the skin. The result is