Sex, Politics, and Comedy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bad Girls: Agency, Revenge, and Redemption in Contemporary Drama

e Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy Bad Girls: Agency, Revenge, and Redemption in Contemporary Drama Courtney Watson, Ph.D. Radford University Roanoke, Virginia, United States [email protected] ABSTRACT Cultural movements including #TimesUp and #MeToo have contributed momentum to the demand for and development of smart, justified female criminal characters in contemporary television drama. These women are representations of shifting power dynamics, and they possess agency as they channel their desires and fury into success, redemption, and revenge. Building on works including Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl and Netflix’s Orange is the New Black, dramas produced since 2016—including The Handmaid’s Tale, Ozark, and Killing Eve—have featured the rise of women who use rule-breaking, rebellion, and crime to enact positive change. Keywords: #TimesUp, #MeToo, crime, television, drama, power, Margaret Atwood, revenge, Gone Girl, Orange is the New Black, The Handmaid’s Tale, Ozark, Killing Eve Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy 37 Watson From the recent popularity of the anti-heroine in novels and films like Gone Girl to the treatment of complicit women and crime-as-rebellion in Hulu’s adaptation of The Handmaid’s Tale to the cultural watershed moments of the #TimesUp and #MeToo movements, there has been a groundswell of support for women seeking justice both within and outside the law. Behavior that once may have been dismissed as madness or instability—Beyoncé laughing wildly while swinging a baseball bat in her revenge-fantasy music video “Hold Up” in the wake of Jay-Z’s indiscretions comes to mind—can be examined with new understanding. -

The Top 101 Inspirational Movies –

The Top 101 Inspirational Movies – http://www.SelfGrowth.com The Top 101 Inspirational Movies Ever Made – by David Riklan Published by Self Improvement Online, Inc. http://www.SelfGrowth.com 20 Arie Drive, Marlboro, NJ 07746 ©Copyright by David Riklan Manufactured in the United States No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without the prior written permission of the Publisher. Limit of Liability / Disclaimer of Warranty: While the authors have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents and specifically disclaim any implied warranties. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. The author shall not be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages. The Top 101 Inspirational Movies – http://www.SelfGrowth.com The Top 101 Inspirational Movies Ever Made – by David Riklan TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 6 Spiritual Cinema 8 About SelfGrowth.com 10 Newer Inspirational Movies 11 Ranking Movie Title # 1 It’s a Wonderful Life 13 # 2 Forrest Gump 16 # 3 Field of Dreams 19 # 4 Rudy 22 # 5 Rocky 24 # 6 Chariots of -

P.O.V. a Danish Journal of Film Studies

Institut for Informations og Medievidenskab Aarhus Universitet p.o.v. A Danish Journal of Film Studies Editor: Richard Raskin Number 8 December 1999 Department of Information and Media Studies University of Aarhus 2 p.o.v. number 8 December 1999 Udgiver: Institut for Informations- og Medievidenskab, Aarhus Universitet Niels Juelsgade 84 DK-8200 Aarhus N Oplag: 750 eksemplarer Trykkested: Trykkeriet i Hovedbygningen (Annette Hoffbeck) Aarhus Universitet ISSN-nr.: 1396-1160 Omslag & lay-out Richard Raskin Articles and interviews © the authors. Frame-grabs from Wings of Desire were made with the kind permission of Wim Wenders. The publication of p.o.v. is made possible by a grant from the Aarhus University Research Foundation. All correspondence should be addressed to: Richard Raskin Institut for Informations- og Medievidenskab Niels Juelsgade 84 8200 Aarhus N e-mail: [email protected] fax: (45) 89 42 1952 telefon: (45) 89 42 1973 This, as well as all previous issues of p.o.v. can be found on the Internet at: http://www.imv.aau.dk/publikationer/pov/POV.html This journal is included in the Film Literature Index. STATEMENT OF PURPOSE The principal purpose of p.o.v. is to provide a framework for collaborative publication for those of us who study and teach film at the Department of Information and Media Science at Aarhus University. We will also invite contributions from colleagues at other departments and at other universities. Our emphasis is on collaborative projects, enabling us to combine our efforts, each bringing his or her own point of view to bear on a given film or genre or theoretical problem. -

OMC | Data Export

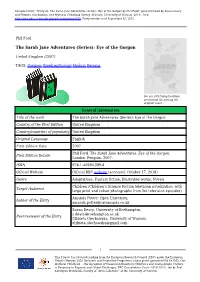

Amanda Potter, "Entry on: The Sarah Jane Adventures (Series): Eye of the Gorgon by Phil Ford", peer-reviewed by Susan Deacy and Elżbieta Olechowska. Our Mythical Childhood Survey (Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2018). Link: http://omc.obta.al.uw.edu.pl/myth-survey/item/550. Entry version as of September 25, 2021. Phil Ford The Sarah Jane Adventures (Series): Eye of the Gorgon United Kingdom (2007) TAGS: Gorgons Greek mythology Medusa Perseus We are still trying to obtain permission for posting the original cover. General information Title of the work The Sarah Jane Adventures (Series): Eye of the Gorgon Country of the First Edition United Kingdom Country/countries of popularity United Kingdom Original Language English First Edition Date 2007 Phil Ford. The Sarah Jane Adventures: Eye of the Gorgon. First Edition Details London: Penguin, 2007. ISBN 978-1-40590-399-8 Official Website Official BBC website (accessed: October 17, 2018) Genre Adaptations, Fantasy fiction, Illustrated works, Novels Children (Children’s Science Fiction television novelization, with Target Audience large print and colour photographs from the television episodes) Amanda Potter, Open University, Author of the Entry [email protected] Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, [email protected] Peer-reviewer of the Entry Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, [email protected] 1 This Project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement No 681202, Our Mythical Childhood... The Reception of Classical Antiquity in Children’s and Young Adults’ Culture in Response to Regional and Global Challenges, ERC Consolidator Grant (2016–2021), led by Prof. -

![Sexuality Is Fluid''[1] a Close Reading of the First Two Seasons of the Series, Analysing Them from the Perspectives of Both Feminist Theory and Queer Theory](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4839/sexuality-is-fluid-1-a-close-reading-of-the-first-two-seasons-of-the-series-analysing-them-from-the-perspectives-of-both-feminist-theory-and-queer-theory-264839.webp)

Sexuality Is Fluid''[1] a Close Reading of the First Two Seasons of the Series, Analysing Them from the Perspectives of Both Feminist Theory and Queer Theory

''Sexuality is fluid''[1] a close reading of the first two seasons of the series, analysing them from the perspectives of both feminist theory and queer theory. It or is it? An analysis of television's The L Word from the demonstrates that even though the series deconstructs the perspectives of gender and sexuality normative boundaries of both gender and sexuality, it can also be said to maintain the ideals of a heteronormative society. The [1]Niina Kuorikoski argument is explored by paying attention to several aspects of the series. These include the series' advertising both in Finland and the ("Seksualność jest płynna" - czy rzeczywiście? Analiza United States and the normative femininity of the lesbian telewizyjnego "The L Word" z perspektywy płci i seksualności) characters. In addition, the article aims to highlight the manner in which the series depicts certain characters which can be said to STRESZCZENIE : Amerykański serial telewizyjny The L Word stretch the normative boundaries of gender and sexuality. Through (USA, emitowany od 2004) opowiada historię grupy lesbijek this, the article strives to give a diverse account of the series' first two i biseksualnych kobiet mieszkających w Los Angeles. Artykuł seasons and further critical discussion of The L Word and its analizuje pierwsze dwa sezony serialu z perspektywy teorii representations. feministycznej i teorii queer. Chociaż serial dekonstruuje normatywne kategorie płci kulturowej i seksualności, można ______________________ również twierdzić, że podtrzymuje on ideały heteronormatywnego The analysis in the article is grounded in feminist thinking and queer społeczeństwa. Przedstawiona argumentacja opiera się m. in. na theory. These theoretical disciplines provide it with two central analizie takich aspektów, jak promocja serialu w Finlandii i w USA concepts that are at the background of the analysis, namely those of oraz normatywna kobiecość postaci lesbijek. -

REALLY BAD GIRLS of the BIBLE the Contemporary Story in Each Chapter Is Fiction

Higg_9781601428615_xp_all_r1_MASTER.template5.5x8.25 5/16/16 9:03 AM Page i Praise for the Bad Girls of the Bible series “Liz Curtis Higgs’s unique use of fiction combined with Scripture and modern application helped me see myself, my past, and my future in a whole new light. A stunning, awesome book.” —R OBIN LEE HATCHER author of Whispers from Yesterday “In her creative, fun-loving way, Liz retells the stories of the Bible. She deliv - ers a knock-out punch of conviction as she clearly illustrates the lessons of Scripture.” —L ORNA DUECK former co-host of 100 Huntley Street “The opening was a page-turner. I know that women are going to read this and look at these women of the Bible with fresh eyes.” —D EE BRESTIN author of The Friendships of Women “This book is a ‘good read’ directed straight at the ‘bad girl’ in all of us.” —E LISA MORGAN president emerita, MOPS International “With a skillful pen and engaging candor Liz paints pictures of modern sit u ations, then uniquely parallels them with the Bible’s ‘bad girls.’ She doesn’t condemn, but rather encourages and equips her readers to become godly women, regardless of the past.” —M ARY HUNT author of Mary Hunt’s Debt-Proof Living Higg_9781601428615_xp_all_r1_MASTER.template5.5x8.25 5/16/16 9:03 AM Page ii “Bad Girls is more than an entertaining romp through fascinating charac - ters. It is a bona fide Bible study in which women (and men!) will see them - selves revealed and restored through the matchless and amazing grace of God.” —A NGELA ELWELL HUNT author of The Immortal “Liz had me from the first paragraph. -

The German/American Exchange on Nazi-Era Art Provenance Research

2017 PREP Exchanges The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (February 5–10) Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (September 24–29) 2018 PREP Exchanges The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (February 25–March 2) Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte, Munich (October 8–12) 2019 PREP Exchanges Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden (Spring) Smithsonian Institution, Provenance Research Initiative, Washington, D.C. (Fall) Major support for the German/American Provenance Research Exchange Program comes from The German Program for Transatlantic Encounters, financed by the European Recovery Program through Germany's Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy, and its Commissioner for Culture and the Media Additional funding comes from the PREP Partner Institutions, The German/American Exchange on the Smithsonian Women's Committee, James P. Hayes, Nazi-Era Art Provenance Research Suzanne and Norman Cohn, and the Ferdinand-Möller-Stiftung, Berlin 3RD PREP Exchange in Los Angeles February 25 — March 2, 2018 Front cover: Photos and auction catalogs from the 1910s in the Getty Research Institute’s provenance research holdings The Getty Research Institute 1200 Getty Center Drive Los Angeles, CA 90049 © 2018Paul J.Getty Trust ORGANIZING PARTNERS Smithsonian Provenance Research Initiative, Smithsonian Institution Washington, D.C. Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz—Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation—National Museums in Berlin) PARTNERS The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York The Getty Research -

Convent Slave Laundries? Magdalen Asylums in Australia

Convent slave laundries? Magdalen asylums in Australia James Franklin* A staple of extreme Protestant propaganda in the first half of the twentieth century was the accusation of ‘convent slave laundries’. Anti-Catholic organs like The Watchman and The Rock regularly alleged extremely harsh conditions in Roman Catholic convent laundries and reported stories of abductions into them and escapes from them.1 In Ireland, the scandal of Magdalen laundries has been the subject of extensive official inquiries.2 Allegations of widespread near-slave conditions and harsh punishments turned out to be substantially true.3 The Irish state has apologized,4 memoirs have been written, compensation paid, a movie made.5 Something similar occurred in England.6 1 ‘Attack on convents’, Argus 21/1/1907, http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/10610696; ‘Abbotsford convent again: another girl abducted’, The Watchman 22/7/1915, http:// trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/111806210; ‘Protestant Federation: Why it is needed: Charge of slavery in convents’, Maitland Daily Mercury 23/4/1921, http://trove.nla.gov. au/ndp/del/article/123726627; ‘Founder of “The Rock” at U.P.A. rally’, Northern Star 2/4/1947, http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/99154812. 2 Commission to Inquire into Child Abuse (Ireland, 2009), ch. 18, http://www. childabusecommission.ie/rpt/pdfs/CICA-VOL3-18.pdf; Report of the Inter-Departmental Committee to establish the facts of State involvement with the Magdalen Laundries (McAleese Report, 2013), http://www.justice.ie/en/ JELR/Pages/MagdalenRpt2013; summary at http://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/feb/05/magdalene-laundries-ireland-state- guilt 3 J.M. -

Mickey Mayhew Phd Final2018.Pdf

‘Skewed intimacies and subcultural identities: Anne Boleyn and the expression of fealty in a social media forum’ Mickey Mayhew A Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Sociology at London South Bank University Supervisors: Doctor Shaminder Takhar (Director of Studies) and Doctor Jenny Owen Faculty of Arts and Human Sciences, Department of Social Sciences & Department of Media and Cultural Studies, London South Bank University 1 Abstract The aim of this research project was the investigation of a subculture surrounding the famous Tudor queen Anne Boleyn; what that possible subculture means for those involved, and if it constituted part of a new phenomenon of female orientated online subcultures; cybersubcultures. Through the analysis of film, TV, historical literature and fiction, the research illustrates how subcultures are perpetuated through generations cyclically. The research then documents the transition from the traditional or ‘classic’ subcultural model of the 60s to the 21st century cybersubculture and fandom, suggesting a new way of thinking about subcultures in a post-subcultural age. The research suggests that the positioning of Anne Boleyn as a feminist icon/role model, based mainly on a media-mediated image, has formed a subculture which thrives on disjointed imagery and discourse in order to form a subculture of peculiarly subtle resistance. This new cybersubculture reflects the ways in which women are now able to use social media to form communities and to communicate, sharing concerns over men and marriage, all whilst percolating around the media-mediated image of Anne Boleyn as their starting point. These interactions – and the similarities they shared with the ‘classic’ subcultural style - form the data for this research project. -

BFI Southbank Will Mark the Centenary of the Weimar Republic with a Major Two-Month Season Running Friday 3 May – Sunday 30 June

Thursday 28 March 2019, London. BFI Southbank will mark the centenary of the Weimar Republic with a major two-month season running Friday 3 May – Sunday 30 June. BEYOND YOUR WILDEST DREAMS: WEIMAR CINEMA 1919-1933 will celebrate one of the most innovative and ground-breaking chapters in the history of cinema. The first major survey of Weimar cinema in London for many years, the season will reveal that the influential body of cinematic work which emerged from this remarkably turbulent era is even richer and more diverse than generally thought. Thanks to brilliant aesthetic and technical innovations, Germany’s film industry was soon second only to Hollywood, catering to a new mass audience through a dazzling range of styles and genres – not only the ‘haunted screen’ horror for which it is still chiefly renowned, but exotic adventure films, historical epics, urban tales, romantic melodramas, social realism and avant-garde experiments. Most surprising perhaps is the wealth of comedies, with gender-bending farces and sparkling musicals such as I Don't Want to Be a Man (Ernst Lubitsch, 1918) and A Blonde Dream (Paul Martin, 1932). But Weimar cinema wasn’t just dazzling entertainment: throughout this period of polarised politics, which was increasingly overshadowed by the rise of Nazism, it also posed vital questions. From an early plea for gay rights – Different from the Others (Richard Oswald, 1919) – to stirring critiques of the capitalist system such as The Threepenny Opera (GW Pabst, 1931) and Kuhle Wampe (Slatan Dudow, 1932) the films still speak urgently to contemporary concerns about a range of social issues. -

La Grande Avventura Di Raoul Walsh

LA GRANDE AVVENTURA DI RAOUL WALSH The Big Adventure of Raoul Walsh Programma.a.cura.di./.Programme curated by. Peter von Bagh Note.di./.Notes by. Paola Cristalli,.Dave Kehr.e.Peter von Bagh 176 Dopo gli omaggi a Josef von Sternberg, Frank Capra, John Ford e After Sternberg, Capra, Ford and Hawks, the name that symbolizes Howard Hawks, ecco il nome che rappresenta l’avventura e il cine- the sense of adventure and pure cinema, action and meditation, ma puro, l’azione e la meditazione, lo spettacolo e il silenzio: Raoul spectacle and silence – Raoul Walsh (1887-1980). In the words of Walsh (1887-1980). Come ha scritto Jean Douchet, i film di Walsh Jean Douchet, Walsh’s films are “an inner adventure”: “This pas- sono “un’avventura interiore”: “Questo shakespeariano passionale sionate Shakespearian is so intensely phisical because, above all, è un regista intensamente fisico perché dipinge prima di tutto il he is painting the tumultuous mental world”. Our series consists tumultuoso mondo mentale”. Il nostro programma si compone di of a full set of silents, too often ignored as indifferent sketches on una selezione di film muti, importanti quanto spesso trascurati, e the way to things to come, plus selected treasures of the sound di alcuni tesori del periodo sonoro, a partire dalla magnifica avven- period, especially the early years which include the magnificent tura in formato panoramico di The Big Trail del 1930. 1930 adventure in widescreen The Big Trail plus some brilliant A Hollywood Walsh fu un ribelle solitario: rifiutò la rete di sicurezza bonuses from later years. -

Information & Bibliothek

DVD / Blu-Ray-Gesamtkatalog der Bibliothek / Catálogo Completo de DVDs e Blu-Rays da Biblioteca Abkürzungen / Abreviações: B = Buch / Roteiro; D = Darsteller / Atores; R = Regie / Diretor; UT = Untertitel / Legendas; dtsch. = deutsch / alemão; engl. = englisch / inglês; port. = portugiesisch / português; franz. = französisch / francês; russ. = russisch / russo; span. = spanisch / espanhol; chin. = chinesisch / chinês; jap. = japanisch / japonês; mehrsprach. = mehrsprachig / plurilingüe; M = Musiker / M úsico; Dir. = Dirigent / Regente; Inter. = Interprete / Intérprete; EST = Einheitssachtitel / Título Original; Zwischent. = Zwischentitel / Entretítulos ● = Audio + Untertitel deutsch / áudio e legendas em alemão Periodika / Periódicos ------------------------------- 05 Kub KuBus. - Bonn: Inter Nationes ● 68. Film 1: Eine Frage des Vertrauens - Die Auflösung des Deutschen Bundestags. Film 2: Stelen im Herzen Berlins - Das Denkmal für die ermordeten Juden Europas. - 2005. - DVD: 30 Min. : farb. ; dtsch., engl., franz., span., + mehrspr. Begleitbuch ; dtsch., russ., chin. UT ; NTSC ; V+Ö. (KuBus , 68) ● 69: Film 1: Im Vorwärtsgang - Frauenfußball in Deutschland. Film 2: Faktor X - Die Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft und die digitale Zukunft. - 2005.- DVD: 30 Min. : farb. ; dtsch., engl., franz., span., + mehrspr. Begleitbuch ; dtsch., russ., chin. UT ; NTSC ; V+Ö. (KuBus ; 69) ● 70. Film 1: Wie deutsch darf man singen? Film 2: Traumberuf Dirigentin. - 2006. - DVD: 30 Min. : farb. ; dtsch., engl., franz., span., + mehrspr. Begleitbuch ; dtsch., russ., chin. UT ; NTSC ; V+Ö. (KuBus ; 70) ● 71. Film 1: Der Maler Jörg Immendorff. Film 2: Der junge deutsche Jazz. - 2006. - DVD: 30 Min. : farb. ; dtsch., engl., franz., span., + mehrspr. Begleitbuch ; dtsch., russ., chin. UT ; NTSC ; V+Ö. (KuBus ; 71) ● 72. Film 1: Die Kunst des Bierbrauens. Film 2: Fortschritt unter der Karosserie. - 2006. - DVD: 30 Min. : farb. ; dtsch., engl., franz., span., + mehrspr.