Performing History Studies in Theatre History & Culture Edited by Thomas Postlewait Performing HISTORY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Top 101 Inspirational Movies –

The Top 101 Inspirational Movies – http://www.SelfGrowth.com The Top 101 Inspirational Movies Ever Made – by David Riklan Published by Self Improvement Online, Inc. http://www.SelfGrowth.com 20 Arie Drive, Marlboro, NJ 07746 ©Copyright by David Riklan Manufactured in the United States No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without the prior written permission of the Publisher. Limit of Liability / Disclaimer of Warranty: While the authors have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents and specifically disclaim any implied warranties. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. The author shall not be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages. The Top 101 Inspirational Movies – http://www.SelfGrowth.com The Top 101 Inspirational Movies Ever Made – by David Riklan TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 6 Spiritual Cinema 8 About SelfGrowth.com 10 Newer Inspirational Movies 11 Ranking Movie Title # 1 It’s a Wonderful Life 13 # 2 Forrest Gump 16 # 3 Field of Dreams 19 # 4 Rudy 22 # 5 Rocky 24 # 6 Chariots of -

P.O.V. a Danish Journal of Film Studies

Institut for Informations og Medievidenskab Aarhus Universitet p.o.v. A Danish Journal of Film Studies Editor: Richard Raskin Number 8 December 1999 Department of Information and Media Studies University of Aarhus 2 p.o.v. number 8 December 1999 Udgiver: Institut for Informations- og Medievidenskab, Aarhus Universitet Niels Juelsgade 84 DK-8200 Aarhus N Oplag: 750 eksemplarer Trykkested: Trykkeriet i Hovedbygningen (Annette Hoffbeck) Aarhus Universitet ISSN-nr.: 1396-1160 Omslag & lay-out Richard Raskin Articles and interviews © the authors. Frame-grabs from Wings of Desire were made with the kind permission of Wim Wenders. The publication of p.o.v. is made possible by a grant from the Aarhus University Research Foundation. All correspondence should be addressed to: Richard Raskin Institut for Informations- og Medievidenskab Niels Juelsgade 84 8200 Aarhus N e-mail: [email protected] fax: (45) 89 42 1952 telefon: (45) 89 42 1973 This, as well as all previous issues of p.o.v. can be found on the Internet at: http://www.imv.aau.dk/publikationer/pov/POV.html This journal is included in the Film Literature Index. STATEMENT OF PURPOSE The principal purpose of p.o.v. is to provide a framework for collaborative publication for those of us who study and teach film at the Department of Information and Media Science at Aarhus University. We will also invite contributions from colleagues at other departments and at other universities. Our emphasis is on collaborative projects, enabling us to combine our efforts, each bringing his or her own point of view to bear on a given film or genre or theoretical problem. -

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read Aeschylus The Persians (472 BC) McCullers A Member of the Wedding The Orestia (458 BC) (1946) Prometheus Bound (456 BC) Miller Death of a Salesman (1949) Sophocles Antigone (442 BC) The Crucible (1953) Oedipus Rex (426 BC) A View From the Bridge (1955) Oedipus at Colonus (406 BC) The Price (1968) Euripdes Medea (431 BC) Ionesco The Bald Soprano (1950) Electra (417 BC) Rhinoceros (1960) The Trojan Women (415 BC) Inge Picnic (1953) The Bacchae (408 BC) Bus Stop (1955) Aristophanes The Birds (414 BC) Beckett Waiting for Godot (1953) Lysistrata (412 BC) Endgame (1957) The Frogs (405 BC) Osborne Look Back in Anger (1956) Plautus The Twin Menaechmi (195 BC) Frings Look Homeward Angel (1957) Terence The Brothers (160 BC) Pinter The Birthday Party (1958) Anonymous The Wakefield Creation The Homecoming (1965) (1350-1450) Hansberry A Raisin in the Sun (1959) Anonymous The Second Shepherd’s Play Weiss Marat/Sade (1959) (1350- 1450) Albee Zoo Story (1960 ) Anonymous Everyman (1500) Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf Machiavelli The Mandrake (1520) (1962) Udall Ralph Roister Doister Three Tall Women (1994) (1550-1553) Bolt A Man for All Seasons (1960) Stevenson Gammer Gurton’s Needle Orton What the Butler Saw (1969) (1552-1563) Marcus The Killing of Sister George Kyd The Spanish Tragedy (1586) (1965) Shakespeare Entire Collection of Plays Simon The Odd Couple (1965) Marlowe Dr. Faustus (1588) Brighton Beach Memoirs (1984 Jonson Volpone (1606) Biloxi Blues (1985) The Alchemist (1610) Broadway Bound (1986) -

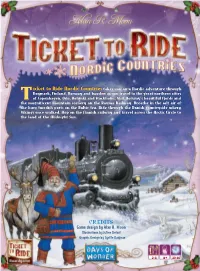

Rules EN 2015 TTR2 Rules Nordic EN 18/05/15 15:51 Page2

[T2RNordic] rules EN 2015_TTR2 rules Nordic EN 18/05/15 15:51 Page2 icket to Ride Nordic Countries takes you on a Nordic adventure through Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden as you travel to the great northern cities T of Copenhagen, Oslo, Helsinki and Stockholm. Visit Norway's beautiful fjords and the magnificent mountain scenery on the Rauma Railway. Breathe in the salt air of the busy Swedish ports on the Baltic Sea. Ride through the Danish countryside where Vikings once walked. Hop-on the Finnish railway and travel across the Arctic Circle to the land of the Midnight Sun. CREDITS Game design by Alan R. Moon Illustrations by Julien Delval Graphic Design by Cyrille Daujean 2-3 8+ 30-60’ [T2RNordic] rules EN 2015_TTR2 rules Nordic EN 18/05/15 15:52 Page3 Components 1 Globetrotter Bonus card u 1 Board map of Scandinavian train routes for the most completed tickets u 120 Colored Train cars (40 each in 3 different colors, plus a few spare) 46 Destination u 157 Illustrated cards: Ticket cards 110 Train cards : 12 of each color, plus 14 Locomotives ∫ ∂ u 3 Wooden Scoring Markers (1 for each player matching the train colors) u 1 Rules booklet Setting up the Game Place the board map in the center of the table. Each player takes a set of 40 Colored Train Cars along with its matching Scoring Marker. Each player places his Scoring Marker on the starting π location next to the 100 number ∂ on the Scoring Track running along the map's border. Throughout the game, each time a player scores points, he will advance his marker accordingly. -

Israel in 1982: the War in Lebanon

Israel in 1982: The War in Lebanon by RALPH MANDEL LS ISRAEL MOVED INTO its 36th year in 1982—the nation cele- brated 35 years of independence during the brief hiatus between the with- drawal from Sinai and the incursion into Lebanon—the country was deeply divided. Rocked by dissension over issues that in the past were the hallmark of unity, wracked by intensifying ethnic and religious-secular rifts, and through it all bedazzled by a bullish stock market that was at one and the same time fuel for and seeming haven from triple-digit inflation, Israelis found themselves living increasingly in a land of extremes, where the middle ground was often inhospitable when it was not totally inaccessible. Toward the end of the year, Amos Oz, one of Israel's leading novelists, set out on a journey in search of the true Israel and the genuine Israeli point of view. What he heard in his travels, as published in a series of articles in the daily Davar, seemed to confirm what many had sensed: Israel was deeply, perhaps irreconcilably, riven by two political philosophies, two attitudes toward Jewish historical destiny, two visions. "What will become of us all, I do not know," Oz wrote in concluding his article on the develop- ment town of Beit Shemesh in the Judean Hills, where the sons of the "Oriental" immigrants, now grown and prosperous, spewed out their loath- ing for the old Ashkenazi establishment. "If anyone has a solution, let him please step forward and spell it out—and the sooner the better. -

Fencing with Wildlife in Mind

COLORADO PARKS & WILDLIFE Fencing with Wildlife in Mind www.cpw.state.co.us ©PHOTO BY SHEILA LAMB©PHOTO BY “Good fences make good neighbors.” —Robert Frost, from Mending Walls A Conversation Starter, Not the Last Word Fences—thousands of types have been invented, and millions of miles have been erected. We live our lives between post, rail, chain link and wire. It’s difficult to imagine neighborhoods, farms, industry and ranches without fences. They define property, confine pets and livestock, and protect that which is dear to us, joining or separating the public and private. For humans, fences make space into place. For wildlife, fences limit travel and access to critical habitat. This publication provides guidelines and details for constructing fences with wildlife in mind. The information it contains has been contributed by wildlife managers, biologists, land managers, farmers, and ranchers. Over time, their observations and research have built a body of knowledge concerning wildlife and fences, including: •A basic understanding of how ungulates cross fences and the fence designs that cause problems for moose, elk, deer, pronghorn, and bighorn sheep. •Fence designs that adequately contain livestock without excluding wildlife. •Fence designs that effectively exclude ungulates, bears, beavers, and other small mammals. This information is intended to open the conversation about fences and wildlife. This is by no means the “last word.” New fencing materials and designs are continually developed. New research on the topic will invariably provide added and improved alternatives. Nonetheless, this publication provides viable options to those who wish to allow safe passage for wildlife or to exclude animals for specific reasons. -

NEW Media Document.Indd

MEDIA RELEASE WICKED is coming to Australia. The hottest musical in the world will open in Melbourne’s Regent Theatre in July 2008. With combined box office sales of $US 1/2 billion, WICKED is already one of the most successful shows in theatre history. WICKED opened on Broadway in October 2003. Since then over two and a half million people have seen WICKED in New York and just over another two million have seen the North American touring production. The smash-hit musical with music and lyrics by Stephen Schwartz (Godspell, Pippin, Academy Award-winner for Pocahontas and The Prince of Egypt) and book by Winnie Holzman (My So Called Life, Once And Again and thirtysomething) is based on the best-selling novel by Gregory Maguire. WICKED is produced by Marc Platt, Universal Pictures, The Araca Group, Jon B. Platt and David Stone. ‘We’re delighted that Melbourne is now set to follow WICKED productions in New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, the North American tour and London’s West End,’ Marc Platt and David Stone said in a joint statement from New York. ‘Melbourne will join new productions springing up around the world over the next 16 months, and we’re absolutely sure that Aussies – and international visitors to Melbourne – will be just as enchanted by WICKED as the audiences are in America and England.’ WICKED will premiere in Tokyo in June; Stuttgart in November; Melbourne in July 2008; and Amsterdam in 2008. Winner of 15 major awards including the Grammy Award and three Tony Awards, WICKED is the untold story of the witches of Oz. -

Download Download

ISSN 2002-3898 © Ken Nielsen and Nordic Theatre Studies DOI: https://doi.org/10.7146/nts.v25i1.110898 Published with support from Nordic Board for Periodicals in the Humanities and Social Sciences (NOP-HS) Gone With the Plague: Negotiating Sexual Citizenship in Crisis Ken Nielsen ABSTRACT This article suggests that two historical performances by the Danish subcultural theatre group Buddha og Bag- bordsindianerne should be understood not simply as underground, amateur cabarets, but rather that they should be theorized as creating a critical temporality, as theorized by David Román. As such, they function to complicate the past and the present in rejecting a discourse of decency and embracing a queerer, more radical sense of citizenship. In other words, conceptualizing these performances as critical temporalities allows us not only to understand two particular theatrical performances of gay male identity and AIDS in Copenhagen in the late 1980s, but also to theorize more deeply embedded tensions between queer identities, temporality, and citizenship. Furthermore, by reading these performances and other performances like them as critical temporalities we reject the willful blindness of traditional theatre histories and make a more radical theatre history possible. Keywords: BIOGRAPHY Ken Nielsen is a Postdoctoral lecturer in the Princeton Writing Program, Princeton University, where he is currently teaching classes ranging from contemporary confession culture to tragedy. He holds a PhD in the- atre studies from The Graduate Center, City University of New York, with an emphasis on Gay and Lesbian Studies from the Center for Lesbian and Gay Studies (CLAGS). In addition, he holds an MA in Theatre Research from the University of Copenhagen. -

Wenders Has Had Monumental Influence on Cinema

“WENDERS HAS HAD MONUMENTAL INFLUENCE ON CINEMA. THE TIME IS RIPE FOR A CELEBRATION OF HIS WORK.” —FORBES WIM WENDERS PORTRAITS ALONG THE ROAD A RETROSPECTIVE THE GOALIE’S ANXIETY AT THE PENALTY KICK / ALICE IN THE CITIES / WRONG MOVE / KINGS OF THE ROAD THE AMERICAN FRIEND / THE STATE OF THINGS / PARIS, TEXAS / TOKYO-GA / WINGS OF DESIRE DIRECTOR’S NOTEBOOK ON CITIES AND CLOTHES / UNTIL THE END OF THE WORLD ( CUT ) / BUENA VISTA SOCIAL CLUB JANUSFILMS.COM/WENDERS THE GOALIE’S ANXIETY AT THE PENALTY KICK PARIS, TEXAS ALICE IN THE CITIES TOKYO-GA WRONG MOVE WINGS OF DESIRE KINGS OF THE ROAD NOTEBOOK ON CITIES AND CLOTHES THE AMERICAN FRIEND UNTIL THE END OF THE WORLD (DIRECTOR’S CUT) THE STATE OF THINGS BUENA VISTA SOCIAL CLUB Wim Wenders is cinema’s preeminent poet of the open road, soulfully following the journeys of people as they search for themselves. During his over-forty-year career, Wenders has directed films in his native Germany and around the globe, making dramas both intense and whimsical, mysteries, fantasies, and documentaries. With this retrospective of twelve of his films—from early works of the New German Cinema Alice( in the Cities, Kings of the Road) to the art-house 1980s blockbusters that made him a household name (Paris, Texas; Wings of Desire) to inquisitive nonfiction looks at world culture (Tokyo-ga, Buena Vista Social Club)—audiences can rediscover Wenders’s vast cinematic world. Booking: [email protected] / Publicity: [email protected] janusfilms.com/wenders BIOGRAPHY Wim Wenders (born 1945) came to international prominence as one of the pioneers of the New German Cinema in the 1970s and is considered to be one of the most important figures in contemporary German film. -

Your Itinerary

Highlights of Scandinavia Your itinerary Start Location Visited Location Plane End Location Cruise Train Over night Ferry Day 1 it destroyed by the Gestapo. Arrive Copenhagen (2 Nights) Included Meals - Breakfast You're in for a whole lot of hygge when you hit the colourful, characterfilled streets of Day 7 Copenhagen, which kickstarts your journey across Scandinavia. This cool capital manages to mix fairy tale with function as you'll come to discover. Spend your day Bergen – Sognefjord (Hafslo) (1 Night) soaking up the sunshine in 17thcentury Nyhavn or rubbing shoulders with the fun Norway's fjord country takes centre stage today as you head to the 'King of the loving locals in Tivoli Gardens, Europe's second oldest amusement park. You'll meet Fjords', Sognefjord. Your scenic drive will pass Tvindefossen waterfall before arriving your Travel Director and fellow travellers for dinner later at your hotel. at the world's longest and deepest fjord. For nature lovers, there's an Optional Experience to board a cruise on the UNESCOlisted Nærøy Fjord whose stunning Comwell Portside Hotel - landscape has inspired painters for centuries. Later, you'll have a rare opportunity as part of an Optional Experience to meet a local Included Meals - Dinner family on their working farm against the backdrop of the fjord, sampling their Day 2 traditions that date back to Viking times. Tonight, join your travel companions for Copenhagen sightseeing and free time dinner at your hotel. Discover why Copenhagen earns its status as one of the world's most liveable cities Hotel - Eikum a place where work and play are perfectly balanced. -

The Danish People's High School

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BUREAU OF EDUCATION 131XLETIN, /1915, No.45 THE DANISH PEOPLE'S HIGH SCHOOL INCLUDING A GENERAL ACCOUNT OF THE EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM OF DENMARK . By MARTIN HEG D PRESIDENT WALDORF COLLEGE. FOREST CITY. IOWA WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1915 4 ,0 ADDITIONAL COPIES 07 THIS PGRLICATIA MAY Bb( RCURROaaoit TAIL SUPISSINAMDENTorDOCUMINTS 00VYRNMSNT PRINTING OPPICIL.,-' WASHINGTON, D. C. AT 20 CENTS COPX CONTENTS. Pass. Letter transmittal Prefat -v note 6 PART I. THE EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM OF DENMARK. Chapter I.Historical development 7 ILOrganization and administration of education 19 II 1. Elementary education 29 IV.Secondary education _ 53 V. University and vocational education 64 PART II. THE DANISH PEOPLE'S HIGH SCHOCIL. VI.Origin of the people's high schools 78 VII. growth of the people's high school 84 schools and their life 99 IX.Alms, curricula, and methods 113 X.Influence and results 129 XI. People's high schools in other countries 142 XII.--Conclusion 154 )tppendix A.Statistical tables 167 B.Bibliography 172 Irma 181 8 LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL DEPARTMENT OF TIIE INTERIOR, BUREAU OF EDUCATION, Washington, September E3, 1915: SIR: The folk high schools of Denmark and other Scandinavian countries are so unique and contain so much of interest to all who are concerned in the preparation,of young men and wothein for higher and better living and for more efficient citizenship that, although two or three' former bulletins of this bureau have been devoted to-a 'description of these schi)ols and their work, I recommend that the manuscript transmitted herewith be published as a bulletin of the Bureau of Education for the purpose of giving a still more com- Jorehensive account of the subject.Those who read this and the 114former bulletins referred to vij11 have a fairly complete account, not only of these.schools, but also of the whole system of rural education of which these sehooli tre an important wt. -

The German-Jewish Experience Revisited Perspectives on Jewish Texts and Contexts

The German-Jewish Experience Revisited Perspectives on Jewish Texts and Contexts Edited by Vivian Liska Editorial Board Robert Alter, Steven E. Aschheim, Richard I. Cohen, Mark H. Gelber, Moshe Halbertal, Geoffrey Hartman, Moshe Idel, Samuel Moyn, Ada Rapoport-Albert, Alvin Rosenfeld, David Ruderman, Bernd Witte Volume 3 The German-Jewish Experience Revisited Edited by Steven E. Aschheim Vivian Liska In cooperation with the Leo Baeck Institute Jerusalem In cooperation with the Leo Baeck Institute Jerusalem. An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. ISBN 978-3-11-037293-9 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-036719-5 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-039332-3 ISSN 2199-6962 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2015 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Cover image: bpk / Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin Typesetting: PTP-Berlin, Protago-TEX-Production GmbH, Berlin Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Preface The essays in this volume derive partially from the Robert Liberles International Summer Research Workshop of the Leo Baeck Institute Jerusalem, 11–25 July 2013.