This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from Explore Bristol Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mccrimmon Mccrimmon

ISSUE #14 APRIL 2010 FREE! NOT FOR RESALE MARC PLATT chats about Point of Entry RICHARD EARL on his roles in Doctor Who and Sherlock Holmes MAGGIE staBLES is back in the studio as Evelyn Smythe! RETURN OF THE McCRIMMON FRazER HINEs Is baCk IN THE TaRdIs! PLUS: Sneak Previews • Exclusive Photos • Interviews and more! EDITORIAL Well, as you read this, Holmes and the Ripper will I do adore it. But it is all-consuming. And it reminded finally be out. As I write this, I have not long finished me of how hard the work is and how dedicated all our doing the sound design, which made me realize one sound designers are. There’s quite an army of them thing in particular: that being executive producer of now. When I became exec producer we only had a Big Finish really does mean that I don’t have time to do handful, but over the last couple of years I have been the sound design for a whole double-CD production. on a recruitment drive, and now we have some great That makes me a bit sad. But what really lifts my spirits new people with us, including Daniel Brett, Howard is listening to the music, which is, at this very moment, Carter, Jamie Robertson and Kelly and Steve at Fool being added by Jamie Robertson. Only ten more Circle Productions, all joining the great guys we’ve been minutes of music to go… although I’m just about to working with for years. Sound design is a very special, download the bulk of Part Two in a about half an hour’s crazy world in which you find yourself listening to every time. -

George Harrison

COPYRIGHT 4th Estate An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF www.4thEstate.co.uk This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2020 Copyright © Craig Brown 2020 Cover design by Jack Smyth Cover image © Michael Ochs Archives/Handout/Getty Images Craig Brown asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins. Source ISBN: 9780008340001 Ebook Edition © April 2020 ISBN: 9780008340025 Version: 2020-03-11 DEDICATION For Frances, Silas, Tallulah and Tom EPIGRAPHS In five-score summers! All new eyes, New minds, new modes, new fools, new wise; New woes to weep, new joys to prize; With nothing left of me and you In that live century’s vivid view Beyond a pinch of dust or two; A century which, if not sublime, Will show, I doubt not, at its prime, A scope above this blinkered time. From ‘1967’, by Thomas Hardy (written in 1867) ‘What a remarkable fifty years they -

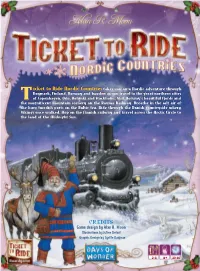

Rules EN 2015 TTR2 Rules Nordic EN 18/05/15 15:51 Page2

[T2RNordic] rules EN 2015_TTR2 rules Nordic EN 18/05/15 15:51 Page2 icket to Ride Nordic Countries takes you on a Nordic adventure through Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden as you travel to the great northern cities T of Copenhagen, Oslo, Helsinki and Stockholm. Visit Norway's beautiful fjords and the magnificent mountain scenery on the Rauma Railway. Breathe in the salt air of the busy Swedish ports on the Baltic Sea. Ride through the Danish countryside where Vikings once walked. Hop-on the Finnish railway and travel across the Arctic Circle to the land of the Midnight Sun. CREDITS Game design by Alan R. Moon Illustrations by Julien Delval Graphic Design by Cyrille Daujean 2-3 8+ 30-60’ [T2RNordic] rules EN 2015_TTR2 rules Nordic EN 18/05/15 15:52 Page3 Components 1 Globetrotter Bonus card u 1 Board map of Scandinavian train routes for the most completed tickets u 120 Colored Train cars (40 each in 3 different colors, plus a few spare) 46 Destination u 157 Illustrated cards: Ticket cards 110 Train cards : 12 of each color, plus 14 Locomotives ∫ ∂ u 3 Wooden Scoring Markers (1 for each player matching the train colors) u 1 Rules booklet Setting up the Game Place the board map in the center of the table. Each player takes a set of 40 Colored Train Cars along with its matching Scoring Marker. Each player places his Scoring Marker on the starting π location next to the 100 number ∂ on the Scoring Track running along the map's border. Throughout the game, each time a player scores points, he will advance his marker accordingly. -

E-ISSN: 2536-4596

e-ISSN: 2536-4596 KARE- Uluslararası Edebiyat, Tarih ve Düşünce Dergisi KARE- International Journal of Literature, History and Philosophy Başlık/ Title: Parody and Mystery in Tom Stoppard’s The Real Inspector Hound and Jumpers Yazar/ Author ORCID ID Kenan KOÇAK 0000-0002-6422-2329 Makale Türü / Type of Article: Araştırma Makalesi / Research Article Yayın Geliş Tarihi / Submission Date: 4 Ekim 2019 Yayına Kabul Tarihi / Acceptance Date: 18 Kasım 2019 Yayın Tarihi / Date Published: 25 Kasım 2019 Web Sitesi: https://karedergi.erciyes.edu.tr/ Makale göndermek için / Submit an Article: http://dergipark.gov.tr/kare Parody and Mystery in Tom Stoppard’s The Real Inspector Hound and Jumpers Yazar: Kenan KOÇAK ∗ Tom Stoppard’ın Gerçek Müfettiş Hound (The Real Inspector Hound) ve Akrobatlar (Jumpers) Oyunlarında Parodi ve Gizem1 Özet: Tom Stoppard, Çekoslavakya doğumlu ve İngilizce’yi sonradan öğrenmiş olması sebebiyle, anadili İngilizce olan yazarlara nazaran dile daha hâkim ve dilin imkanlarını daha iyi kullanabilen, kelimelerle oynamada mahir; komik diyaloglar, yanlış anlaşılmaya mahal vermeler ve beklenmedik cevaplar yaratabilen usta bir oyun yazarıdır. Kendisi öyle olduğunu reddetse de oyunlarında kimliğin ve hafızanın önemi, gerçek ve görünen arasındaki ilişki, hayatın sıkıntıları, kendinden ve kendinden önceki yazarlardan esinlenme ve ödünç alma gibi postmodern ve absürd tiyatronun tipik özelliklerini görmek mümkündür. İlk defa 1968 yılında sergilenen Gerçek Müfettiş Hound (The Real Inspector Hound) oyunu Agatha Christie’nin 1952 yapımı Fare Kapanı (The Mousetrap) oyununun bir parodisiyken Akrobatlar (Jumpers) akademik felsefenin satirik bir eleştirisidir. Stoppard, bu makalede incelenen Gerçek Müfettiş Hound ve Akrobatlar adlı oyunlarında kurgusunu oyunlarının başında yarattığı bir gizem üzerine inşa eder. Bu gizem Gerçek Müfettiş Hound’da sahneye diğer aktörlerce fark edilmeyen bir ceset koyarak gerçekleştirilirken Akrobatlar’ın en başında akrobatlardan birinin öldürülmesi ve kimin öldürdüğünün de oyun boyunca söylenmemesiyle sağlanır. -

Shakes in Love STUDYGUIDE

Study Guide for Educators Based on the screenplay by Marc Norman and Tom Stoppard Adapted for the stage by Lee Hall Lyrics by Carolyn Leigh Music by Paddy Cunneen This production of Shakespeare In Love is generously sponsored by: Emily and Dene Hurlbert Linda Stafford Burrows Ron and Mary Nanning Ron Tindall, RN Shakespeare in Love is presented by special arrangement with Samuel French Inc 1 Welcome to the Pacific Conservatory Theatre A NOTE TO THE TEACHER Thank you for bringing your students to the Pacific Conservatory Theatre at Allan Hancock College. Here are some helpful hints for your visit to the Marian Theatre. The top priority of our staff is to provide an enjoyable day of live theatre for you and your students. We offer you this study guide as a tool to prepare your students prior to the performance. SUGGESTIONS FOR STUDENT ETIQUETTE Note-able behavior is a vital part of theater for youth. Going to the theater is not a casual event. It is a special occasion. If students are prepared properly, it will be a memorable, educational experience they will remember for years. 1. Have students enter the theater in a single file. Chaperones should be one adult for every ten students. Our ushers will assist you with locating your seats. Please wait until the usher has seated your party before any rearranging of seats to avoid injury and confusion. While seated, teachers should space themselves so they are visible, between every groups of ten students. Teachers and adults must remain with their group during the entire performance. -

Plays to Read for Furman Theatre Arts Majors

1 PLAYS TO READ FOR FURMAN THEATRE ARTS MAJORS Aeschylus Agamemnon Greek 458 BCE Euripides Medea Greek 431 BCE Sophocles Oedipus Rex Greek 429 BCE Aristophanes Lysistrata Greek 411 BCE Terence The Brothers Roman 160 BCE Kan-ami Matsukaze Japanese c 1300 anonymous Everyman Medieval 1495 Wakefield master The Second Shepherds' Play Medieval c 1500 Shakespeare, William Hamlet Elizabethan 1599 Shakespeare, William Twelfth Night Elizabethan 1601 Marlowe, Christopher Doctor Faustus Jacobean 1604 Jonson, Ben Volpone Jacobean 1606 Webster, John The Duchess of Malfi Jacobean 1612 Calderon, Pedro Life is a Dream Spanish Golden Age 1635 Moliere Tartuffe French Neoclassicism 1664 Wycherley, William The Country Wife Restoration 1675 Racine, Jean Baptiste Phedra French Neoclassicism 1677 Centlivre, Susanna A Bold Stroke for a Wife English 18th century 1717 Goldoni, Carlo The Servant of Two Masters Italian 18th century 1753 Gogol, Nikolai The Inspector General Russian 1842 Ibsen, Henrik A Doll's House Modern 1879 Strindberg, August Miss Julie Modern 1888 Shaw, George Bernard Mrs. Warren's Profession Modern Irish 1893 Wilde, Oscar The Importance of Being Earnest Modern Irish 1895 Chekhov, Anton The Cherry Orchard Russian 1904 Pirandello, Luigi Six Characters in Search of an Author Italian 20th century 1921 Wilder, Thorton Our Town Modern 1938 Brecht, Bertolt Mother Courage and Her Children Epic Theatre 1939 Rodgers, Richard & Oscar Hammerstein Oklahoma! Musical 1943 Sartre, Jean-Paul No Exit Anti-realism 1944 Williams, Tennessee The Glass Menagerie Modern -

Performing History Studies in Theatre History & Culture Edited by Thomas Postlewait Performing HISTORY

Performing history studies in theatre history & culture Edited by Thomas Postlewait Performing HISTORY theatrical representations of the past in contemporary theatre Freddie Rokem University of Iowa Press Iowa City University of Iowa Press, Library of Congress Iowa City 52242 Cataloging-in-Publication Data Copyright © 2000 by the Rokem, Freddie, 1945– University of Iowa Press Performing history: theatrical All rights reserved representations of the past in Printed in the contemporary theatre / by Freddie United States of America Rokem. Design by Richard Hendel p. cm.—(Studies in theatre http://www.uiowa.edu/~uipress history and culture) No part of this book may be repro- Includes bibliographical references duced or used in any form or by any and index. means, without permission in writing isbn 0-87745-737-5 (cloth) from the publisher. All reasonable steps 1. Historical drama—20th have been taken to contact copyright century—History and criticism. holders of material used in this book. 2. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945), The publisher would be pleased to make in literature. 3. France—His- suitable arrangements with any whom tory—Revolution, 1789–1799— it has not been possible to reach. Literature and the revolution. I. Title. II. Series. The publication of this book was generously supported by the pn1879.h65r65 2000 University of Iowa Foundation. 809.2Ј9358—dc21 00-039248 Printed on acid-free paper 00 01 02 03 04 c 54321 for naama & ariel, and in memory of amitai contents Preface, ix Introduction, 1 1 Refractions of the Shoah on Israeli Stages: -

NEW Media Document.Indd

MEDIA RELEASE WICKED is coming to Australia. The hottest musical in the world will open in Melbourne’s Regent Theatre in July 2008. With combined box office sales of $US 1/2 billion, WICKED is already one of the most successful shows in theatre history. WICKED opened on Broadway in October 2003. Since then over two and a half million people have seen WICKED in New York and just over another two million have seen the North American touring production. The smash-hit musical with music and lyrics by Stephen Schwartz (Godspell, Pippin, Academy Award-winner for Pocahontas and The Prince of Egypt) and book by Winnie Holzman (My So Called Life, Once And Again and thirtysomething) is based on the best-selling novel by Gregory Maguire. WICKED is produced by Marc Platt, Universal Pictures, The Araca Group, Jon B. Platt and David Stone. ‘We’re delighted that Melbourne is now set to follow WICKED productions in New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, the North American tour and London’s West End,’ Marc Platt and David Stone said in a joint statement from New York. ‘Melbourne will join new productions springing up around the world over the next 16 months, and we’re absolutely sure that Aussies – and international visitors to Melbourne – will be just as enchanted by WICKED as the audiences are in America and England.’ WICKED will premiere in Tokyo in June; Stuttgart in November; Melbourne in July 2008; and Amsterdam in 2008. Winner of 15 major awards including the Grammy Award and three Tony Awards, WICKED is the untold story of the witches of Oz. -

Written by Ben Woolf Edited by Sam Maynard and Katherine Igoe-Ewer Rehearsal and Production Photography by Johan Persson CONTENTS BACKGROUNDPRODUCTIONRESOURCES

Written by Ben Woolf Edited by Sam Maynard and Katherine Igoe-Ewer Rehearsal and Production Photography by Johan Persson CONTENTS BACKGROUNDPRODUCTIONRESOURCES Contents Introduction 3 Section 1: Background to CLOSER 4 CLOSER: An introduction 5 Characters 6 CLOSER in Context 10 Section 2: The Donmar’s Production 15 Cast and Creative Team 16 Rehearsal Diaries 17 An Interview with Playwright Patrick Marber 21 An Interview with the Cast of CLOSER 26 Section 3: Resources 30 Spotlight on Deborah Andrews, Costume Supervisor 31 Workshop Exercises 35 Bibliography 39 2 CONTENTS BACKGROUNDPRODUCTIONRESOURCES Introduction Welcome to this Behind the Scenes Guide to the Donmar Warehouse production of Patrick Marber’s CLOSER, directed by David Leveaux. The following pages contain an exclusive insight into the process of bringing this production from page to stage. Written by playwright and director Patrick Marber, CLOSER was critically acclaimed when it premiered at the National Theatre in 1997, winning Olivier, Evening Standard and New York Drama Critic’s Circle Awards. It has since been produced in the West End, Broadway, around the world and adapted into an international movie. This is its first major London revival. This guide aims to set the play and the production in context. It includes conversations with Patrick Marber and the cast who bring the characters to life. There are also extracts from Resident Assistant Director Zoé Ford’s rehearsal diary and practical exercises designed for use in the classroom. The guide has a particular focus on costume and includes a conversation with Deborah Andrews, the production’s costume supervisor, whose role is crucial in finding the right look for each character. -

Objects in Tom Stoppard's Arcadia

Cercles 22 (2012) ANIMAL, VEGETABLE OR MINERAL? OBJECTS IN TOM STOPPARD’S ARCADIA SUSAN BLATTÈS Université Stendhal—Grenoble 3 The simplicity of the single set in Arcadia1 with its rather austere furniture, bare floor and uncurtained windows has been pointed out by critics, notably in comparison with some of Stoppard’s earlier work. This relatively timeless set provides, on one level, an unchanging backdrop for the play’s multiple complexities in terms of plot, ideas and temporal structure. However we should not conclude that the set plays a secondary role in the play since the mysteries at the centre of the plot can only be solved here and with this particular group of characters. Furthermore, I would like to suggest that the on-stage objects play a similarly vital role by gradually transforming our first impressions and contributing to the multi-layered meaning of the play. In his study on the theatre from a phenomenological perspective, Bert O. States writes: “Theater is the medium, par excellence, that consumes the real in its realest forms […] Its permanent spectacle is the parade of objects and processes in transit from environment to imagery” [STATES 1985 : 40]. This paper will look at some of the parading or paraded objects in Arcadia. The objects are many and various, as can be seen in the list provided in the Samuel French acting edition (along with lists of lighting and sound effects). We will see that there are not only many different objects, but also that each object can be called upon to assume different functions at different moments, hence the rather playful question in the title of this paper (an allusion to the popular game “Twenty Questions” in which the identity of an object has to be guessed), suggesting we consider the objects as a kind of challenge to the spectator, who is set the task of identifying and interpreting them. -

Synesthetic Landscapes in Harold Pinter's Theatre

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2010 Synesthetic Landscapes in Harold Pinter’s Theatre: A Symbolist Legacy Graça Corrêa Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1645 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Synesthetic Landscapes in Harold Pinter’s Theatre: A Symbolist Legacy Graça Corrêa A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Theatre in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2010 ii © 2010 GRAÇA CORRÊA All Rights Reserved iii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Theatre in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________ ______________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Daniel Gerould ______________ ______________________________ Date Executive Officer Jean Graham-Jones Supervisory Committee ______________________________ Mary Ann Caws ______________________________ Daniel Gerould ______________________________ Jean Graham-Jones THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iv Abstract Synesthetic Landscapes in Harold Pinter’s Theatre: A Symbolist Legacy Graça Corrêa Adviser: Professor Daniel Gerould In the light of recent interdisciplinary critical approaches to landscape and space , and adopting phenomenological methods of sensory analysis, this dissertation explores interconnected or synesthetic sensory “scapes” in contemporary British playwright Harold Pinter’s theatre. By studying its dramatic landscapes and probing into their multi-sensory manifestations in line with Symbolist theory and aesthetics , I argue that Pinter’s theatre articulates an ecocritical stance and a micropolitical critique. -

Past Productions

Past Productions 2017-18 2012-2013 2008-2009 A Doll’s House Born Yesterday The History Boys Robert Frost: This Verse Sleuth Deathtrap Business Peter Pan Les Misérables Disney’s The Little The Importance of Being The Year of Magical Mermaid Earnest Thinking Only Yesterday Race Laughter on the 23rd Disgraced No Sex Please, We're Floor Noises Off British The Glass Menagerie Nunsense Take Two 2016-17 Macbeth 2011-2012 2007-2008 A Christmas Carol Romeo and Juliet How the Other Half Trick or Treat Boeing-Boeing Loves Red Hot Lovers Annie Doubt Grounded Les Liaisons Beauty & the Beast Mamma Mia! Dangereuses The Price M. Butterfly Driving Miss Daisy 2015-16 Red The Elephant Man Our Town Chicago The Full Monty Mary Poppins Mad Love 2010-2011 2006-2007 Hound of the Amadeus Moon Over Buffalo Baskervilles The 39 Steps I Am My Own Wife The Mountaintop The Wizard of Oz Cats Living Together The Search for Signs of Dancing At Lughnasa Intelligent Life in the The Crucible 2014-15 Universe A Chorus Line A Christmas Carol The Real Thing Mid-Life! The Crisis Blithe Spirit The Rainmaker Musical Clybourne Park Evita Into the Woods 2005-2006 Orwell In America 2009-2010 Lend Me A Tenor Songs for a New World Hamlet A Number Parallel Lives Guys And Dolls 2013-14 The 25th Annual I Love You, You're Twelve Angry Men Putnam County Perfect, Now Change God of Carnage Spelling Bee The Lion in Winter White Christmas I Hate Hamlet Of Mice and Men Fox on the Fairway Damascus Cabaret Good People A Walk in the Woods Spitfire Grill Greater Tuna Past Productions 2004-2005 2000-2001