The Writer and Director

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Liana De Camarqo Leão Âk£ MA D, T994

Liana de Camarqo Leão METAVISION& ENTRANCES AND EXífS IN TOM Âk£ MA D, Dissertação apresentada ao Curso de Pós-Graduação em Literaturas de Língua Inglesa, do Setor de Ciências Humanas, Letras e Artes da Universidade Federal do Paraná, para a obtenção do grau dc Mestre cm Letras. Orientador: Proí1. Dr\ Anna Stegh Camati. t994 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS >1 man had need have sound ears to hear himseíffranifij criticised; and as títere are feu' who can endure to hear it without ùeing nett fed, those who hazard the undertaking of it to us manifest a singular effect of friendship; for 'tis . to (ove siticerehj indeed, to venture to wound and off end us, for our ou>ngood. (Montaigne) First of all, I would like to acknowledge the enlightening, patient and constructive guidance I have received, throughout my graduate studies, from my advisor, Dr. Anna Stegh Camati. I also wish to thank the generous commentaries and suggestions of Dr. Thomas Beebee from Pennsylvania State University and Dr. Graham Huggan from Harvard University. I am extremely grateful to Dr. David Shephard, and to my colleague Cristiane Busato, who patiently revised parts of this dissertation. Finally, my affection and gratitude to my husband, Luiz Otávio Leáo, for his support in providing free time for me to study. iii TADLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT vi ; RESUMO viii 1 INTRODUCTION: Till« CIUTICO' ANXllfiTY" FOH TOM STOPPARD'B ORIGINALrrY 1 2 THE FRAMEWORK OF ROSENCRANTZ AND OUILDENSTERN ARE DEAD: STOPPARJD'S VISION OF REALITY AS SET OF INTERCHANGEABLE FRAMES 20 3 TWO PRUFROCKEAN SHAKESPEARE CHARACTERS IN SEARCH OF GODOT 50 3.1 ELIOT'S INFLUENCE: A HUNDRED INDECISIONS BEFORE DYING 64 3.2 PIRANDELLO'S INFLUENCE: TWO CHARACTERS IN SEARCH OF THEMSELVES 58 3.3 BECKETT'S INFLUENCE: WAITING FOR A PLOT... -

The Playing Field the Basketball Court LAW II

LAW I – The Playing Field ● The Basketball Court LAW II - The Ball · Size #4 · Bounce: 55-65 cm on first bounce · Material: Leather or other suitable material (i.e., not dangerous) LAW III - Number of Players · Minimum Number of Players to Start Match: 5, one of whom shall be a goalkeeper and one of whom shall be female · Maximum Number of Players on the Field of Play: 6, one of whom shall be a goalkeeper and one of whom shall be female · Substitution Limit: None · Substitution Method: "Flying substitution" (all players but the goalkeeper enter and leave as they please; goalkeeper substitutions can only be made when the ball is out of play and with a referee's consent) LAW IV - Players' Equipment Usual Equipment: Numbered shirts, shorts, socks, protective shin-guards and footwear with rubber soles LAW V - Main Referee · Duties: Enforce the laws, apply the advantage rule, keep a record of all incidents before, during and after game, stop game when deemed necessary, caution or expel players guilty of misconduct, violent conduct or other ungentlemanly behavior, allow no others to enter the pitch, stop game to have injured players removed, signal for game to be restarted after every stoppage, decide that the ball meets with the stipulated requirements. · Position: The side opposite to the player benches LAW VI: Second Referee · Duties: Same as Main Referee , ensuring that substitutions are carried out properly, and keeping a check on the 1-minute time-out. · Position: The same side as the player benches LAW VII - Timekeeper · Duties: Start game clock after kick-off, stop it when the ball is out of play, and restart it after all restarts; keep a check on 2-minutepunishment for sending off; indicate end of first half and match with some sort of sound; record time-outs and fouls (and indicate when a team has exceeded the 5-foul limit); record game stoppages, scorers, players cautioned and sent off, and other information relevant to the game. -

E-ISSN: 2536-4596

e-ISSN: 2536-4596 KARE- Uluslararası Edebiyat, Tarih ve Düşünce Dergisi KARE- International Journal of Literature, History and Philosophy Başlık/ Title: Parody and Mystery in Tom Stoppard’s The Real Inspector Hound and Jumpers Yazar/ Author ORCID ID Kenan KOÇAK 0000-0002-6422-2329 Makale Türü / Type of Article: Araştırma Makalesi / Research Article Yayın Geliş Tarihi / Submission Date: 4 Ekim 2019 Yayına Kabul Tarihi / Acceptance Date: 18 Kasım 2019 Yayın Tarihi / Date Published: 25 Kasım 2019 Web Sitesi: https://karedergi.erciyes.edu.tr/ Makale göndermek için / Submit an Article: http://dergipark.gov.tr/kare Parody and Mystery in Tom Stoppard’s The Real Inspector Hound and Jumpers Yazar: Kenan KOÇAK ∗ Tom Stoppard’ın Gerçek Müfettiş Hound (The Real Inspector Hound) ve Akrobatlar (Jumpers) Oyunlarında Parodi ve Gizem1 Özet: Tom Stoppard, Çekoslavakya doğumlu ve İngilizce’yi sonradan öğrenmiş olması sebebiyle, anadili İngilizce olan yazarlara nazaran dile daha hâkim ve dilin imkanlarını daha iyi kullanabilen, kelimelerle oynamada mahir; komik diyaloglar, yanlış anlaşılmaya mahal vermeler ve beklenmedik cevaplar yaratabilen usta bir oyun yazarıdır. Kendisi öyle olduğunu reddetse de oyunlarında kimliğin ve hafızanın önemi, gerçek ve görünen arasındaki ilişki, hayatın sıkıntıları, kendinden ve kendinden önceki yazarlardan esinlenme ve ödünç alma gibi postmodern ve absürd tiyatronun tipik özelliklerini görmek mümkündür. İlk defa 1968 yılında sergilenen Gerçek Müfettiş Hound (The Real Inspector Hound) oyunu Agatha Christie’nin 1952 yapımı Fare Kapanı (The Mousetrap) oyununun bir parodisiyken Akrobatlar (Jumpers) akademik felsefenin satirik bir eleştirisidir. Stoppard, bu makalede incelenen Gerçek Müfettiş Hound ve Akrobatlar adlı oyunlarında kurgusunu oyunlarının başında yarattığı bir gizem üzerine inşa eder. Bu gizem Gerçek Müfettiş Hound’da sahneye diğer aktörlerce fark edilmeyen bir ceset koyarak gerçekleştirilirken Akrobatlar’ın en başında akrobatlardan birinin öldürülmesi ve kimin öldürdüğünün de oyun boyunca söylenmemesiyle sağlanır. -

Shakes in Love STUDYGUIDE

Study Guide for Educators Based on the screenplay by Marc Norman and Tom Stoppard Adapted for the stage by Lee Hall Lyrics by Carolyn Leigh Music by Paddy Cunneen This production of Shakespeare In Love is generously sponsored by: Emily and Dene Hurlbert Linda Stafford Burrows Ron and Mary Nanning Ron Tindall, RN Shakespeare in Love is presented by special arrangement with Samuel French Inc 1 Welcome to the Pacific Conservatory Theatre A NOTE TO THE TEACHER Thank you for bringing your students to the Pacific Conservatory Theatre at Allan Hancock College. Here are some helpful hints for your visit to the Marian Theatre. The top priority of our staff is to provide an enjoyable day of live theatre for you and your students. We offer you this study guide as a tool to prepare your students prior to the performance. SUGGESTIONS FOR STUDENT ETIQUETTE Note-able behavior is a vital part of theater for youth. Going to the theater is not a casual event. It is a special occasion. If students are prepared properly, it will be a memorable, educational experience they will remember for years. 1. Have students enter the theater in a single file. Chaperones should be one adult for every ten students. Our ushers will assist you with locating your seats. Please wait until the usher has seated your party before any rearranging of seats to avoid injury and confusion. While seated, teachers should space themselves so they are visible, between every groups of ten students. Teachers and adults must remain with their group during the entire performance. -

William and Mary Theatre Main Stage Productions

WILLIAM AND MARY THEATRE MAIN STAGE PRODUCTIONS 1926-1927 1934-1935 1941-1942 The Goose Hangs High The Ghosts of Windsor Park Gas Light Arms and the Man Family Portrait 1927-1928 The Romantic Age The School for Husbands You and I The Jealous Wife Hedda Gabler Outward Bound 1935-1936 1942-1943 1928-1929 The Unattainable Thunder Rock The Enemy The Lying Valet The Male Animal The Taming of the Shrew The Cradle Song *Bach to Methuselah, Part I Candida Twelfth Night *Man of Destiny Squaring the Circle 1929-1930 1936-1937 The Mollusc Squaring the Circle 1943-1944 Anna Christie Death Takes a Holiday Papa is All Twelfth Night The Gondoliers The Patriots The Royal Family A Trip to Scarborough Tartuffe Noah Candida 1930-1931 Vergilian Pageant 1937-1938 1944-1945 The Importance of Being Earnest The Night of January Sixteenth Quality Street Just Suppose First Lady Juno and the Paycock The Merchant of Venice The Mikado Volpone Enter Madame Liliom Private Lives 1931-1932 1938-1939 1945-1946 Sun-Up Post Road Pygmalion Berkeley Square RUR Murder in the Cathedral John Ferguson The Pirates of Penzance Ladies in Retirement As You Like It Dear Brutus Too Many Husbands 1932-1933 1939-1940 1946-1947 Outward Bound The Inspector General Arsenic and Old Lace Holiday Kind Lady Arms and the Man The Recruiting Officer Our Town The Comedy of Errors Much Ado About Nothing Hay Fever Joan of Lorraine 1933-1934 1940-1941 1947-1948 Quality Street You Can’t Take It with You The Skin of Our Teeth Hotel Universe Night Must Fall Blithe Spirit The Swan Mary of Scotland MacBeth -

Othello and Its Rewritings, from Nineteenth-Century Burlesque to Post- Colonial Tragedy

Black Rams and Extravagant Strangers: Shakespeare’s Othello and its Rewritings, from Nineteenth-Century Burlesque to Post- Colonial Tragedy Catherine Ann Rosario Goldsmiths, University of London PhD thesis 1 Declaration I declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own. 2 Acknowledgements Firstly, I want to thank my supervisor John London for his immense generosity, as it is through countless discussions with him that I have been able to crystallise and evolve my ideas. I should also like to thank my family who, as ever, have been so supportive, and my parents, in particular, for engaging with my research, and Ebi for being Ebi. Talking things over with my friends, and getting feedback, has also been very helpful. My particular thanks go to Lucy Jenks, Jay Luxembourg, Carrie Byrne, Corin Depper, Andrew Bryant, Emma Pask, Tony Crowley and Gareth Krisman, and to Rob Lapsley whose brilliant Theory evening classes first inspired me to return to academia. Lastly, I should like to thank all the assistance that I have had from Goldsmiths Library, the British Library, Senate House Library, the Birmingham Shakespeare Collection at Birmingham Central Library, Shakespeare’s Birthplace Trust and the Shakespeare Centre Library and Archive. 3 Abstract The labyrinthine levels through which Othello moves, as Shakespeare draws on myriad theatrical forms in adapting a bald little tale, gives his characters a scintillating energy, a refusal to be domesticated in language. They remain as Derridian monsters, evading any enclosures, with the tragedy teetering perilously close to farce. Because of this fragility of identity, and Shakespeare’s radical decision to have a black tragic protagonist, Othello has attracted subsequent dramatists caught in their own identity struggles. -

A Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2002 A Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays. Bonny Ball Copenhaver East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Copenhaver, Bonny Ball, "A Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays." (2002). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 632. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/632 This Dissertation - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays A dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Analysis East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Education in Educational Leadership and Policy Analysis by Bonny Ball Copenhaver May 2002 Dr. W. Hal Knight, Chair Dr. Jack Branscomb Dr. Nancy Dishner Dr. Russell West Keywords: Gender Roles, Feminism, Modernism, Postmodernism, American Theatre, Robbins, Glaspell, O'Neill, Miller, Williams, Hansbury, Kennedy, Wasserstein, Shange, Wilson, Mamet, Vogel ABSTRACT The Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays by Bonny Ball Copenhaver The purpose of this study was to describe how gender was portrayed and to determine how gender roles were depicted and defined in a selection of Modern and Postmodern American plays. -

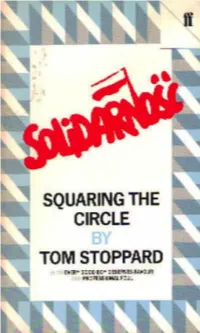

SQUARING the CIRCLE Also Available from Faber & Faber

SQUARING THE CIRCLE Also available from Faber & Faber by Tom Stoppard UNDISCOVERED COUNTRY (a version of Arthur Schnitzler's Das weite Land) ON THE RAZZLE (adapted from Johann Nestroy's Einen Jux will er sich machen) THE REAL THING THE DOG IT WAS THAT DIED and other plays FOUR PLAYS FOR RADIO Artist Descending a Staircase Where Are They Now? If You're Glad I'll be Frank Albert's Bridge SQUARING THE CIRCLE BY TOM STOPPARD t1 faber andfaber BOSTON • LONDON First published in the UK in 1984 First published in the USA in 1985 by Faber & Faber, Inc. 39 Thompson Street Winchester, MA 01890 © Tom Stoppard, 1984 All rights whatsoever in this play are strictly reserved, and all enquiries should be directed to Fraser and Dunlop (Scripts), Ltd., 91 Regent Street, London, WlR 8RU, England All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher, except for brief passages quoted by a reviewer Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Stoppard, Tom. Squaring the circle. I. Title. PR6069.T6S6 1985 822'.914 84-28732 ISBN 0-571-12538-7 (pbk.) IN TRODUC TION At the beginning of 1982, about a month after the imposition of martial law in Poland, a film producer named Fred Brogger suggested that I should write a television film about Solidarity. Thus began a saga, only moderately exceptional by these standards, which may be worth recounting as an example of the perils which sometimes attend the offspring of an Anglo-American marriage. -

On the Razzle by Tom Stoppard, Johann Nestroy #UL2XDHNVFOK

On the Razzle Tom Stoppard, Johann Nestroy Click here if your download doesn"t start automatically On the Razzle Tom Stoppard, Johann Nestroy On the Razzle Tom Stoppard, Johann Nestroy Comedy Characters: 15 male, 10 female, extras, plus 6 musicians. Various interior and exterior sets or unit set. This recent hit in London is a free adaptation of the 19th century farce by Johann Nestroy that provided the plot for Thornton Wilder's The Merchant of Yonkers, which led to The Matchmaker, which led to Hello, Dolly. The story is basically one long chase, chiefly after two naughty grocer's assistants who, when their master goes off on a binge with a new mistress, escape to Vienna on a spree. "While preserving the beautiful intricacies of this construction, Stoppard has embellished Razzle with a dazzle of verbal wit an unremitting firework display of puns, crossword puzzle tricks and sly sexual innuendos." London Daily Telegraph . "Apart from Jumpers and The Importance of Being Earnest there may be no script in English funnier than On the Razzle." London Observer. Download On the Razzle ...pdf Read Online On the Razzle ...pdf Download and Read Free Online On the Razzle Tom Stoppard, Johann Nestroy From reader reviews: Thomas Britton: Why don't make it to be your habit? Right now, try to prepare your time to do the important work, like looking for your favorite book and reading a guide. Beside you can solve your problem; you can add your knowledge by the publication entitled On the Razzle. Try to make book On the Razzle as your friend. -

Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Moral Luck in Medical Ethics and Practical Politics Thesis How to cite: Dickenson, Donna (1989). Moral Luck in Medical Ethics and Practical Politics. PhD thesis. The Open University. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 1989 The Author Version: Version of Record Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Luri Î umvtKbff y DX88774 11NRESTR\CTEB Moral Luck in Medical Ethics and Practical Politics Donna Dickenson, B.A., M.Sc. (Econ.) Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Philosophy Faculty of Arts June 1989 No part of this material has previously been submitted for a degree or other qualification at the Open University or any other institution. l^at(L oj SLibmis^ioA *. 2A bh J iin€/ I1S4 J^aké. û|. a w a ri ; L(-bH Ockûbe.P ProQ uest Number: 27758699 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. in the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 27758699 Published by ProQuest LLC (2019). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. -

This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from Explore Bristol Research

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from Explore Bristol Research, http://research-information.bristol.ac.uk Author: Park-Finch, Heebon Title: Hypertextuality and polyphony in Tom Stoppard's stage plays General rights Access to the thesis is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Public License. A copy of this may be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This license sets out your rights and the restrictions that apply to your access to the thesis so it is important you read this before proceeding. Take down policy Some pages of this thesis may have been removed for copyright restrictions prior to having it been deposited in Explore Bristol Research. However, if you have discovered material within the thesis that you consider to be unlawful e.g. breaches of copyright (either yours or that of a third party) or any other law, including but not limited to those relating to patent, trademark, confidentiality, data protection, obscenity, defamation, libel, then please contact [email protected] and include the following information in your message: •Your contact details •Bibliographic details for the item, including a URL •An outline nature of the complaint Your claim will be investigated and, where appropriate, the item in question will be removed from public view as soon as possible. Hypertextuality and Polyphony in Tom Stoppard's Stage Plays Heebon Park-Finch A dissertation submitted to the University of Bristol in