Convent Slave Laundries? Magdalen Asylums in Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bad Girls: Agency, Revenge, and Redemption in Contemporary Drama

e Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy Bad Girls: Agency, Revenge, and Redemption in Contemporary Drama Courtney Watson, Ph.D. Radford University Roanoke, Virginia, United States [email protected] ABSTRACT Cultural movements including #TimesUp and #MeToo have contributed momentum to the demand for and development of smart, justified female criminal characters in contemporary television drama. These women are representations of shifting power dynamics, and they possess agency as they channel their desires and fury into success, redemption, and revenge. Building on works including Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl and Netflix’s Orange is the New Black, dramas produced since 2016—including The Handmaid’s Tale, Ozark, and Killing Eve—have featured the rise of women who use rule-breaking, rebellion, and crime to enact positive change. Keywords: #TimesUp, #MeToo, crime, television, drama, power, Margaret Atwood, revenge, Gone Girl, Orange is the New Black, The Handmaid’s Tale, Ozark, Killing Eve Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy 37 Watson From the recent popularity of the anti-heroine in novels and films like Gone Girl to the treatment of complicit women and crime-as-rebellion in Hulu’s adaptation of The Handmaid’s Tale to the cultural watershed moments of the #TimesUp and #MeToo movements, there has been a groundswell of support for women seeking justice both within and outside the law. Behavior that once may have been dismissed as madness or instability—Beyoncé laughing wildly while swinging a baseball bat in her revenge-fantasy music video “Hold Up” in the wake of Jay-Z’s indiscretions comes to mind—can be examined with new understanding. -

![Sexuality Is Fluid''[1] a Close Reading of the First Two Seasons of the Series, Analysing Them from the Perspectives of Both Feminist Theory and Queer Theory](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4839/sexuality-is-fluid-1-a-close-reading-of-the-first-two-seasons-of-the-series-analysing-them-from-the-perspectives-of-both-feminist-theory-and-queer-theory-264839.webp)

Sexuality Is Fluid''[1] a Close Reading of the First Two Seasons of the Series, Analysing Them from the Perspectives of Both Feminist Theory and Queer Theory

''Sexuality is fluid''[1] a close reading of the first two seasons of the series, analysing them from the perspectives of both feminist theory and queer theory. It or is it? An analysis of television's The L Word from the demonstrates that even though the series deconstructs the perspectives of gender and sexuality normative boundaries of both gender and sexuality, it can also be said to maintain the ideals of a heteronormative society. The [1]Niina Kuorikoski argument is explored by paying attention to several aspects of the series. These include the series' advertising both in Finland and the ("Seksualność jest płynna" - czy rzeczywiście? Analiza United States and the normative femininity of the lesbian telewizyjnego "The L Word" z perspektywy płci i seksualności) characters. In addition, the article aims to highlight the manner in which the series depicts certain characters which can be said to STRESZCZENIE : Amerykański serial telewizyjny The L Word stretch the normative boundaries of gender and sexuality. Through (USA, emitowany od 2004) opowiada historię grupy lesbijek this, the article strives to give a diverse account of the series' first two i biseksualnych kobiet mieszkających w Los Angeles. Artykuł seasons and further critical discussion of The L Word and its analizuje pierwsze dwa sezony serialu z perspektywy teorii representations. feministycznej i teorii queer. Chociaż serial dekonstruuje normatywne kategorie płci kulturowej i seksualności, można ______________________ również twierdzić, że podtrzymuje on ideały heteronormatywnego The analysis in the article is grounded in feminist thinking and queer społeczeństwa. Przedstawiona argumentacja opiera się m. in. na theory. These theoretical disciplines provide it with two central analizie takich aspektów, jak promocja serialu w Finlandii i w USA concepts that are at the background of the analysis, namely those of oraz normatywna kobiecość postaci lesbijek. -

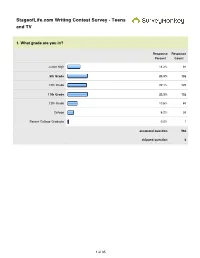

Stageoflife.Com Writing Contest Survey - Teens and TV

StageofLife.com Writing Contest Survey - Teens and TV 1. What grade are you in? Response Response Percent Count Junior High 14.3% 81 9th Grade 23.3% 132 10th Grade 22.1% 125 11th Grade 23.3% 132 12th Grade 10.6% 60 College 6.2% 35 Recent College Graduate 0.2% 1 answered question 566 skipped question 0 1 of 35 2. How many TV shows (30 - 60 minutes) do you watch in an average week during the school year? Response Response Percent Count 20+ (approx 3 shows per day) 21.7% 123 14 (approx 2 shows per day) 11.3% 64 10 (approx 1.5 shows per day) 9.0% 51 7 (approx. 1 show per day) 15.7% 89 3 (approx. 1 show every other 25.8% 146 day) 1 (you watch one show a week) 14.5% 82 0 (you never watch TV) 1.9% 11 answered question 566 skipped question 0 3. Do you watch TV before you leave for school in the morning? Response Response Percent Count Yes 15.7% 89 No 84.3% 477 answered question 566 skipped question 0 2 of 35 4. Do you have a TV in your bedroom? Response Response Percent Count Yes 38.7% 219 No 61.3% 347 answered question 566 skipped question 0 5. Do you watch TV with your parents? Response Response Percent Count Yes 60.6% 343 No 39.4% 223 If yes, which show(s) do you watch as a family? 302 answered question 566 skipped question 0 6. Overall, do you think TV is too violent? Response Response Percent Count Yes 28.3% 160 No 71.7% 406 answered question 566 skipped question 0 3 of 35 7. -

Tribeca Film in Partnership with American Express Presents with Film 4, UK Film Council, Scottish Screen and Wild Bunch a Bluel

Tribeca Film in Partnership with American Express presents with Film 4, UK Film Council, Scottish Screen and Wild Bunch a blueLight, Fidelite Films, Studio Urania production NEDS Winner – Best Film, Evening Standard British Film Awards Winner – Golden Shell for Best Film, San Sebastian Film Festival Winner – Silver Shell for Best Actor, Conor McCarron San Sebastian Film Festival Winner- Young British Performer of the Year, Conor McCarron London Film Critics’ Circle Awards US Premiere Tribeca Film Festival 2011 Available on VOD Nationwide: April 20-June 23, 2011 May 13, 2011- Los Angeles June 17, 2011 – Miami Available August 23 on DVD PRESS CONTACTS Distributor: Publicity: ID PR Tammie Rosen Dani Weinstein Tribeca Film Sara Serlen 212-941-2003 Sheri Goldberg [email protected] 212-334-0333 375 Greenwich Street [email protected] New York, NY 10013 150 West 30th Street, 19th Floor New York, NY 10001 1 SYNOPSIS “If you want a NED, I‟ll give you a fucking NED!” Directed by the acclaimed actor/director Peter Mullan (MY NAME IS JOE, THE MAGDALENE SISTERS) NEDS, so called Non-Educated Delinquents, takes place in the gritty, savage and often violent world of 1970‟s Glasgow. On the brink of adolescence, young John McGill is a bright and sensitive boy, eager to learn and full of promise. But, the cards are stacked against him. Most of the adults in his life fail him in one way or another. His father is a drunken violent bully and his teachers – punishing John for the „sins‟ of his older brother, Benny – are down on him from the start. -

Andrew Scarborough

www.cam.co.uk Email [email protected] Address Andrew 55-59 Shaftesbury Avenue London Scarborough W1D 6LD Telephone +44 (0) 20 7292 0600 Television Title Role Director Production EMMERDALE Graham Various ITV WOLFBLOOD Hartington Jonathan Dower BBC VICTORIA Captain Childers Various Mammoth Screen JAMAICA INN Magistrate Bassatt Phillipa Lowthorne BBC Television DOWNTON ABBEY Tim Drewe Philip John Carnival for ITV Lightworkers Media for The THE BIBLE Joshua Tony Mitchell History Channel OUR GIRL Sergeant Peters David Drury BBC SILENT WITNESS DI Jeff Hart Richard Clark BBC Television SILK DS Adam Lambert Jeremy Webb BBC Television EASTENDERS Carter Dan Wilson BBC Television HIDDEN Ben Lander Niall McCormick BBC Television DOCTORS Martin Venning Sean Gleeson BBC Television HOLBY CITY Tim Campbell Paul Gibson BBC Television SPOOKS Stephen Hillier Alrick Riley BBC Television DOCTORS DS Vince Blackwell Piotr Szkopiak BBC Television Dr Jonathan Ormerod THE ROYAL TODAY - ITV (Regular) HOLBY CITY - - BBC TELEVISION ROMAN MYTHS Jo Sephus - BBC Television Stuart Diamond (Regular SURBURBIAN SHOOT OUT - Channel 5 series 2) BAD GIRLS (Series 7) Kevin Spears (Regular) Shed Productions for ITV - Stuart Diamond (Regular SUBURBIAN SHOOT OUT - Channel 5 series 1) ROME Milo - BBC Television/ HBO EYES DOWN Philip - BBC TELEVISION HEARTS AND BONES SERIES 2 Michael OWen (Regular) - BBC Television CORONATION STREET Harvey - ITV HEARTS AND BONES SERIES 1 Michael Owen (Regular) - BBC Television THE INNOCENT Mark - Yorkshire Television HEARTBEAT Martin Weller - -

Teachers' Responsibilities for Responding to Bullying

Journal of Instruct ional Pedagogies Making a difference for the bullied: teachers’ responsibilities for responding to bullying Janet F. McCarra Mississippi State University —Meridian Campus Jeanne Forrester Albuquerque Public Schools, NM Abstract Bullying continues to be a challenging issue for classroom teachers. The authors provide seven recommendations to prevent bullying and for intervention if bullying occurs: (a) know the forms of bullying and recognize the effects, (b) promote a positive classroom environment, (c) teach a variety of conflict resolution strategies, (d) use bibliotherapy, (e) respond to incidents of bullying, (f) help student s develop new roles, and (g) provide positive role modeling. Keywords: bullying, cyberbullying, teachers’ roles, conflict resolution, bibliotherapy Making a difference, Page 1 Journal of Instruct ional Pedagogies Another child has died —not due to a deadly disease or a horrible car accident but by his own hand. He committed suicide because of bullying ( Tresniowski, A., Egan, N. W., Herbst, D., Triggs, C., Messer, L., Fowler, J., Levy, D. S., & Shabeeb, N., 2010). Bullying is certainly not a new issue (Graham, 20 10). Perhaps everyone can think of a time or man y times when he/she was bullied (or was the bully). Education Week (2010) reported these statistics released by the Josephson Institute of Ethics: (a) 435 of 43,000 high school students said they had been bu llied, and (b) 50% admitted to bullying. Bullying is “a chronic institutional problem leading to psychological impairment, depression and suicide” (Olson, 2008, p. 9). The United States Department of Education held a bullying summit in August 2010 an d encouraged school leaders to take action against bullying (Da vis, 2011). -

Known Nursery Rhymes Residencies Fruit Eaten Remembered World

13 Nov. 1995 – Leah Betts in coma after taking ecstasy 26 Sep. 2007 – Myanmar government, using extreme force, cracks down on protests Blockbusters Bestall, A. – Rupert Annual 1982 Pratchett, T. – Soul Music Celery Hilden, Linda The Tortoise and the Eagle Beverly Hills Cop Goodfellas Speed Peanut Brittle Dial M for Murder Russ Abbott Arena Coast To Coast Gary Numan Live Rammstein Vast Ready to Rumble (Dreamcast) Known Nursery Rhymes 22 Nov. 1995 – Rosemary West sentenced to life imprisonment 06 Oct. 2007 – Musharraf breezes to easy re-election in Pakistan Buckaroo Bestall, A. – Rupert Annual 1984 Pratchett, T. - Sorcery Chard Hill, Debbie The Jackdaw and the Fox Beverly Hills Cop 2 The Goonies Speed 2 Pear Drops Dinnerladies The Ruth Rendell Mysteries Aretha Franklin Cochine Gene McDaniels The Living End Ramones Vegastones Resident Evil (Various) All Around the Mulberry Bush 14 Dec. 1995 – Bosnia peace accord 05 Nov. 2007 – Thousands of lawyers take to the streets to protest the state of emergency rule in Pakistan. Chess Bestall, A. – Rupert Annual 1985 Pratchett, T. – The Streets of Ankh-Morpork Chickpea Hiscock, Anna-Marie The Boy and the Wolf Bicentennial Man The Good, The Bad and the Ugly Spider Man Picnic Doctor Who The Saint Armand Van Helden Cockney Rebel Gene Pitney Lizzy Mercier Descloux Randy Crawford The Velvet Underground Robocop (Commodore 64) As I Was Going to St. Ives 02 Jan. 1996 – US Peacekeepers enter Bosnia 09 Nov. 2007 – Police barricade the city of Rawalpindi where opposition leader Benazir Bhutto plans a protest Chinese Checkers Bestall, A. – Rupert Annual 1988 Pratchett, T. -

Irish Film Institute What Happened After? 15

Irish Film Studyguide Tony Tracy Contents SECTION ONE A brief history of Irish film 3 Recurring Themes 6 SECTION TWO Inside I’m Dancing INTRODUCTION Cast & Synopsis 7 This studyguide has been devised to accompany the Irish film strand of our Transition Year Moving Image Module, the pilot project of the Story and Structure 7 Arts Council Working Group on Film and Young People. In keeping Key Scene Analysis I 7 with TY Guidelines which suggest a curriculum that relates to the Themes 8 world outside school, this strand offers students and teachers an opportunity to engage with and question various representations Key Scene Analysis II 9 of Ireland on screen. The guide commences with a brief history Student Worksheet 11 of the film industry in Ireland, highlighting recurrent themes and stories as well as mentioning key figures. Detailed analyses of two films – Bloody Sunday Inside I'm Dancing and Bloody Sunday – follow, along with student worksheets. Finally, Lenny Abrahamson, director of the highly Cast & Synopsis 12 successful Adam & Paul, gives an illuminating interview in which he Making & Filming History 12/13 outlines the background to the story, his approach as a filmmaker and Characters 13/14 his response to the film’s achievements. We hope you find this guide a useful and stimulating accompaniment to your teaching of Irish film. Key Scene Analysis 14 Alicia McGivern Style 15 Irish FIlm Institute What happened after? 15 References 16 WRITER – TONY TRACY Student Worksheet 17 Tony Tracy was former Senior Education Officer at the Irish Film Institute. During his time at IFI, he wrote the very popular Adam & Paul Introduction to Film Studies as well as notes for teachers on a range Interview with Lenny Abrahamson, director 18 of films including My Left Foot, The Third Man, and French Cinema. -

The Stigma of Having an Abortion: Development of a Scale and Characteristics of Women Experiencing Abortion Stigma

The Stigma of Having an Abortion: Development of a Scale and Characteristics of Women Experiencing Abortion Stigma CONTEXT: Although abortion is common in the United States, women who have abortions report signifi cant social By Kate Cockrill, stigma. Currently, there is no standard measure for individual-level abortion stigma, and little is known about the Ushma D. social and demographic characteristics associated with it. Upadhyay, Janet Turan and Diana METHODS: To create a measure of abortion stigma, an initial item pool was generated using abortion story content Greene Foster analysis and refi ned using cognitive interviews. In 2011, the fi nal item pool was used to assess individual-level abor- tion stigma among 627 women at 13 U.S. Planned Parenthood health centers who reported a previous abortion. Factor analysis was conducted on the survey responses to reduce the number of items and to establish scale validity Kate Cockrill is research analyst, and reliability. Diff erences in level of reported abortion stigma were examined with multivariable linear regression. Ushma D. Upadhyay is assistant research RESULTS: Factor analysis revealed a four-factor model for individual-level abortion stigma: worries about judg- scientist, and Diana ment, isolation, self-judgment and community condemnation (Cronbach’s alphas, 0.8–0.9). Catholic and Protestant Greene Foster is women experienced higher levels of stigma than nonreligious women (coeffi cients, 0.23 and 0.18, respectively). On associate professor, all at Advancing the subscales, women with the strongest religious beliefs had higher levels of self-judgment and greater perception New Standards in of community condemnation than only somewhat religious women. -

Resources for Teaching Magdalene Laundries.Pdf

RESOURCES FOR TEACHING IRELAND’S MAGDALENE LAUNDRIES JUSTICE FOR MAGDALENES RESEARCH • Justice for Magdalenes Research Website (2014-): http://jfmresearch.com/ • Justice for Magdalenes Website (2008-2013): http://www.magdalenelaundries.com/index.htm • Justice for Magdalenes Research Archive: http://repository.wit.ie/JFMA/ • Adoption Rights Alliance: http://www.adoptionrightsalliance.com/ • Clann Project (JFMR/ARA): http://clannproject.org/ JUSTICE FOR MAGDALENES CAMPAIGN, 2009-2013 • http://jfmresearch.com/home/jfm-political-campaign-2009-2013/ ACADEMIC ARTICLES ON THE JUSTICE FOR MAGDALENES CAMPAIGN • O’Donnell, Katherine. “Academics Becoming Activists: Reflections on Some Ethical Issues of the Justice for Magdalenes Campaign.” Irishness on the Margins: Minority and Dissident Identities, edited by Pilar Villar-Argáiz, Palgrave-Macmillan, 2018, pp. 77-100. • O’Rouke, Maeve and James M. Smith. “Ireland’s Magdalene Laundries: Confronting a History Not Yet in the Past.” A Century of Progress? Irish Women Reflect, edited by Alan Hayes and Máire Meagher, Arlen House, 2016, pp. 107-34. • O’Rourke, Maeve. “The Justice for Magdalenes Campaign.” Implementing International Human Rights: Perspectives from Ireland, edited by S. Egan, Bloomsbury, 2016. • Smith, James. “The Justice for Magdalenes Campaign.” In Plain Sight: Responding to the Ferns, Ryan, Murphy and Cloyne Reports, edited by Carole Holohan, Amnesty International-Ireland, 2011. Pp. 372- 77. ADVOCACY JOURNALISM BY JUSTICE FOR MAGDALENES RESEARCH • http://jfmresearch.com/publications/opinion-editorials/ ADVOCACY LECTURES/TALKS BY JUSTICE FOR MAGDALENE RESEARCH • O’Rourke, Maeve. “Why apologise today for historic abuse?” TEDxUCD, 2015. o https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OgjH7zCXFok ——. “Ireland’s Magdalene Laundries.” TEDxHolborn, 2014. o https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xb0d-lOJx9U • Smith, James M. -

Guest Biographies: * Distribution, Sales and Financing Executives * Other Panel & Roundtable Moderators/Speakers London

Guest biographies: * Distribution, sales and financing executives * Other Panel & Roundtable moderators/speakers London Production Finance Market (PFM) Company Profile The London Production Finance Market (PFM) occurs each October in association with The BFI London Film Festival and is supported by the London Development Agency, UK Film Council, UK Trade and Investment (UKTI), Skillset, City of London Corporation and Peacefulfish. The invitation-only PFM last year registered 50 producers and more than 150 projects with US$1.16 billion of production value and nearly 60 financing guests including UGC, Rai Cinema, Miramax, Studio Canal, Lionsgate, Nordisk, Ingenious, Celluloid Dreams, Aramid, Focus, Natixis, Bank of Ireland, Sony Pictures Classics, Warner Bros. and Paramount. Film London is the UK capital's film and media agency. It sustains, promotes and develops London as a major international film-making and film cultural capital. This includes all the screen industries based in London - film, television, video, commercials and new interactive media. Helena MacKenzie Helena Mackenzie started her career in the film industry at the age of 19 when she thought she would try and get a job in the entertainment industry as a way out of going to Medical School. It worked! Many years and a few jobs later she is now the Head of International at Film London. Her journey to Film London has crossed many paths of international production, distribution and international sales. At Film London, she devised and runs the Film Passport Programme, runs the London UK Film Focus and the Production Finance Market (PFM), as well as working with emerging markets such as China, India and Russia. -

Bad Girls Handout Revised

STEPHANIE DRAY LILY OF THE NILE A NOVEL OF www.stephaniedray.com CLEOPATRA’S : DAUGHTER Hits Bookshelves January 2011 A survey of women’s history through the eyes of a historical fiction Bad Girls of the Ancient World novelist. HOW TO FALL AFOUL OF THE PATRIARCHY IN THREE EASY STEPS PICK UP A WEAPON Though examples of warrior women can be found in ancient literature even before the appearance of the Amazons in Homer’s tales, women who fought were considered to be unnatural. DABBLE IN PHILOSOPHY, RELIGION OR MAGIC For the ancients, religion was mostly a matter Queen Cleopatra VII, of Egypt for the state. The idea that a god of the pantheon might take a personal interest in a woman beyond seducing her or punishing her was preposterous. Consequently, priestesses were often viewed with suspicion. Alexander the Great’s mother, Olympias, was always suspected of sorcery, in part, because King Phillip fell in love with her during a religious initiation. Queen Zenobia of Palmyra Olympias of Macedonia BE SEXY Ancient man feared female sexuality and the These historical women have been painted and sway it might have over his better judgment. sculpted throughout the ages. If well-behaved The surest propaganda against an ancient women seldom make history, this should tell you queen was to depict her as a licentious seductress; a charge that has never clung with something about these ladies. more tenacity to any woman than it has to Cleopatra VII of Egypt. Copyright © 2011 Stephanie Dray, All Rights Reserved BAD GIRLS OF THE ANCIENT WORLD! PAGE2 Queen Dido commits suicide Pierre-Narcisse, baron Guérin’s painting of the famous but fictional romance between Dido and Aeneas Timeline & Relationships Dido of Carthage 800 BC Cleopatra Selene’s husband, King Dido Juba II, claimed descent from this legendary queen Queen Dido of Carthage (also Olympias of Macedonia 375 BC Alexander the Great was the son known as Elissa) was of this ambitious woman.