The Stigma of Having an Abortion: Development of a Scale and Characteristics of Women Experiencing Abortion Stigma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bad Girls: Agency, Revenge, and Redemption in Contemporary Drama

e Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy Bad Girls: Agency, Revenge, and Redemption in Contemporary Drama Courtney Watson, Ph.D. Radford University Roanoke, Virginia, United States [email protected] ABSTRACT Cultural movements including #TimesUp and #MeToo have contributed momentum to the demand for and development of smart, justified female criminal characters in contemporary television drama. These women are representations of shifting power dynamics, and they possess agency as they channel their desires and fury into success, redemption, and revenge. Building on works including Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl and Netflix’s Orange is the New Black, dramas produced since 2016—including The Handmaid’s Tale, Ozark, and Killing Eve—have featured the rise of women who use rule-breaking, rebellion, and crime to enact positive change. Keywords: #TimesUp, #MeToo, crime, television, drama, power, Margaret Atwood, revenge, Gone Girl, Orange is the New Black, The Handmaid’s Tale, Ozark, Killing Eve Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy 37 Watson From the recent popularity of the anti-heroine in novels and films like Gone Girl to the treatment of complicit women and crime-as-rebellion in Hulu’s adaptation of The Handmaid’s Tale to the cultural watershed moments of the #TimesUp and #MeToo movements, there has been a groundswell of support for women seeking justice both within and outside the law. Behavior that once may have been dismissed as madness or instability—Beyoncé laughing wildly while swinging a baseball bat in her revenge-fantasy music video “Hold Up” in the wake of Jay-Z’s indiscretions comes to mind—can be examined with new understanding. -

![Sexuality Is Fluid''[1] a Close Reading of the First Two Seasons of the Series, Analysing Them from the Perspectives of Both Feminist Theory and Queer Theory](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4839/sexuality-is-fluid-1-a-close-reading-of-the-first-two-seasons-of-the-series-analysing-them-from-the-perspectives-of-both-feminist-theory-and-queer-theory-264839.webp)

Sexuality Is Fluid''[1] a Close Reading of the First Two Seasons of the Series, Analysing Them from the Perspectives of Both Feminist Theory and Queer Theory

''Sexuality is fluid''[1] a close reading of the first two seasons of the series, analysing them from the perspectives of both feminist theory and queer theory. It or is it? An analysis of television's The L Word from the demonstrates that even though the series deconstructs the perspectives of gender and sexuality normative boundaries of both gender and sexuality, it can also be said to maintain the ideals of a heteronormative society. The [1]Niina Kuorikoski argument is explored by paying attention to several aspects of the series. These include the series' advertising both in Finland and the ("Seksualność jest płynna" - czy rzeczywiście? Analiza United States and the normative femininity of the lesbian telewizyjnego "The L Word" z perspektywy płci i seksualności) characters. In addition, the article aims to highlight the manner in which the series depicts certain characters which can be said to STRESZCZENIE : Amerykański serial telewizyjny The L Word stretch the normative boundaries of gender and sexuality. Through (USA, emitowany od 2004) opowiada historię grupy lesbijek this, the article strives to give a diverse account of the series' first two i biseksualnych kobiet mieszkających w Los Angeles. Artykuł seasons and further critical discussion of The L Word and its analizuje pierwsze dwa sezony serialu z perspektywy teorii representations. feministycznej i teorii queer. Chociaż serial dekonstruuje normatywne kategorie płci kulturowej i seksualności, można ______________________ również twierdzić, że podtrzymuje on ideały heteronormatywnego The analysis in the article is grounded in feminist thinking and queer społeczeństwa. Przedstawiona argumentacja opiera się m. in. na theory. These theoretical disciplines provide it with two central analizie takich aspektów, jak promocja serialu w Finlandii i w USA concepts that are at the background of the analysis, namely those of oraz normatywna kobiecość postaci lesbijek. -

History of Legalization of Abortion in the United States of America in Political and Religious Context and Its Media Presentation

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DSpace at University of West Bohemia Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Bakalářská práce History of legalization of abortion in the United States of America in political and religious context and its media presentation Klára Čížková Plzeň 2017 Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Katedra románských jazyků Studijní program Filologie Studijní obor Cizí jazyky pro komerční praxi Kombinace angličtina – francouzština Bakalářská práce History of legalization of abortion in the United States of America in political and religious context and its media presentation Klára Čížková Vedoucí práce: Ing. BcA. Milan Kohout Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury Fakulta filozofická Západočeské univerzity v Plzni Plzeň 2017 Prohlašuji, že jsem práci zpracovala samostatně a použila jen uvedených pramenů a literatury. Plzeň, duben 2017 ……………………… Na tomto místě bych ráda poděkovala vedoucímu bakalářské práce Ing. BcA. Milanu Kohoutovi za cenné rady a odbornou pomoc, které mi při zpracování poskytl. Dále bych ráda poděkovala svému partnerovi a své rodině za podporu a trpělivost. Plzeň, duben 2017 ……………………… Table of contents 1 Introduction........................................................................................................1 2 History of abortion.............................................................................................3 2.1 19th Century.......................................................................................................3 -

Convent Slave Laundries? Magdalen Asylums in Australia

Convent slave laundries? Magdalen asylums in Australia James Franklin* A staple of extreme Protestant propaganda in the first half of the twentieth century was the accusation of ‘convent slave laundries’. Anti-Catholic organs like The Watchman and The Rock regularly alleged extremely harsh conditions in Roman Catholic convent laundries and reported stories of abductions into them and escapes from them.1 In Ireland, the scandal of Magdalen laundries has been the subject of extensive official inquiries.2 Allegations of widespread near-slave conditions and harsh punishments turned out to be substantially true.3 The Irish state has apologized,4 memoirs have been written, compensation paid, a movie made.5 Something similar occurred in England.6 1 ‘Attack on convents’, Argus 21/1/1907, http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/10610696; ‘Abbotsford convent again: another girl abducted’, The Watchman 22/7/1915, http:// trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/111806210; ‘Protestant Federation: Why it is needed: Charge of slavery in convents’, Maitland Daily Mercury 23/4/1921, http://trove.nla.gov. au/ndp/del/article/123726627; ‘Founder of “The Rock” at U.P.A. rally’, Northern Star 2/4/1947, http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/99154812. 2 Commission to Inquire into Child Abuse (Ireland, 2009), ch. 18, http://www. childabusecommission.ie/rpt/pdfs/CICA-VOL3-18.pdf; Report of the Inter-Departmental Committee to establish the facts of State involvement with the Magdalen Laundries (McAleese Report, 2013), http://www.justice.ie/en/ JELR/Pages/MagdalenRpt2013; summary at http://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/feb/05/magdalene-laundries-ireland-state- guilt 3 J.M. -

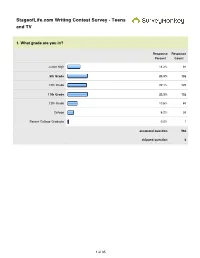

Stageoflife.Com Writing Contest Survey - Teens and TV

StageofLife.com Writing Contest Survey - Teens and TV 1. What grade are you in? Response Response Percent Count Junior High 14.3% 81 9th Grade 23.3% 132 10th Grade 22.1% 125 11th Grade 23.3% 132 12th Grade 10.6% 60 College 6.2% 35 Recent College Graduate 0.2% 1 answered question 566 skipped question 0 1 of 35 2. How many TV shows (30 - 60 minutes) do you watch in an average week during the school year? Response Response Percent Count 20+ (approx 3 shows per day) 21.7% 123 14 (approx 2 shows per day) 11.3% 64 10 (approx 1.5 shows per day) 9.0% 51 7 (approx. 1 show per day) 15.7% 89 3 (approx. 1 show every other 25.8% 146 day) 1 (you watch one show a week) 14.5% 82 0 (you never watch TV) 1.9% 11 answered question 566 skipped question 0 3. Do you watch TV before you leave for school in the morning? Response Response Percent Count Yes 15.7% 89 No 84.3% 477 answered question 566 skipped question 0 2 of 35 4. Do you have a TV in your bedroom? Response Response Percent Count Yes 38.7% 219 No 61.3% 347 answered question 566 skipped question 0 5. Do you watch TV with your parents? Response Response Percent Count Yes 60.6% 343 No 39.4% 223 If yes, which show(s) do you watch as a family? 302 answered question 566 skipped question 0 6. Overall, do you think TV is too violent? Response Response Percent Count Yes 28.3% 160 No 71.7% 406 answered question 566 skipped question 0 3 of 35 7. -

Andrew Scarborough

www.cam.co.uk Email [email protected] Address Andrew 55-59 Shaftesbury Avenue London Scarborough W1D 6LD Telephone +44 (0) 20 7292 0600 Television Title Role Director Production EMMERDALE Graham Various ITV WOLFBLOOD Hartington Jonathan Dower BBC VICTORIA Captain Childers Various Mammoth Screen JAMAICA INN Magistrate Bassatt Phillipa Lowthorne BBC Television DOWNTON ABBEY Tim Drewe Philip John Carnival for ITV Lightworkers Media for The THE BIBLE Joshua Tony Mitchell History Channel OUR GIRL Sergeant Peters David Drury BBC SILENT WITNESS DI Jeff Hart Richard Clark BBC Television SILK DS Adam Lambert Jeremy Webb BBC Television EASTENDERS Carter Dan Wilson BBC Television HIDDEN Ben Lander Niall McCormick BBC Television DOCTORS Martin Venning Sean Gleeson BBC Television HOLBY CITY Tim Campbell Paul Gibson BBC Television SPOOKS Stephen Hillier Alrick Riley BBC Television DOCTORS DS Vince Blackwell Piotr Szkopiak BBC Television Dr Jonathan Ormerod THE ROYAL TODAY - ITV (Regular) HOLBY CITY - - BBC TELEVISION ROMAN MYTHS Jo Sephus - BBC Television Stuart Diamond (Regular SURBURBIAN SHOOT OUT - Channel 5 series 2) BAD GIRLS (Series 7) Kevin Spears (Regular) Shed Productions for ITV - Stuart Diamond (Regular SUBURBIAN SHOOT OUT - Channel 5 series 1) ROME Milo - BBC Television/ HBO EYES DOWN Philip - BBC TELEVISION HEARTS AND BONES SERIES 2 Michael OWen (Regular) - BBC Television CORONATION STREET Harvey - ITV HEARTS AND BONES SERIES 1 Michael Owen (Regular) - BBC Television THE INNOCENT Mark - Yorkshire Television HEARTBEAT Martin Weller - -

Teachers' Responsibilities for Responding to Bullying

Journal of Instruct ional Pedagogies Making a difference for the bullied: teachers’ responsibilities for responding to bullying Janet F. McCarra Mississippi State University —Meridian Campus Jeanne Forrester Albuquerque Public Schools, NM Abstract Bullying continues to be a challenging issue for classroom teachers. The authors provide seven recommendations to prevent bullying and for intervention if bullying occurs: (a) know the forms of bullying and recognize the effects, (b) promote a positive classroom environment, (c) teach a variety of conflict resolution strategies, (d) use bibliotherapy, (e) respond to incidents of bullying, (f) help student s develop new roles, and (g) provide positive role modeling. Keywords: bullying, cyberbullying, teachers’ roles, conflict resolution, bibliotherapy Making a difference, Page 1 Journal of Instruct ional Pedagogies Another child has died —not due to a deadly disease or a horrible car accident but by his own hand. He committed suicide because of bullying ( Tresniowski, A., Egan, N. W., Herbst, D., Triggs, C., Messer, L., Fowler, J., Levy, D. S., & Shabeeb, N., 2010). Bullying is certainly not a new issue (Graham, 20 10). Perhaps everyone can think of a time or man y times when he/she was bullied (or was the bully). Education Week (2010) reported these statistics released by the Josephson Institute of Ethics: (a) 435 of 43,000 high school students said they had been bu llied, and (b) 50% admitted to bullying. Bullying is “a chronic institutional problem leading to psychological impairment, depression and suicide” (Olson, 2008, p. 9). The United States Department of Education held a bullying summit in August 2010 an d encouraged school leaders to take action against bullying (Da vis, 2011). -

Known Nursery Rhymes Residencies Fruit Eaten Remembered World

13 Nov. 1995 – Leah Betts in coma after taking ecstasy 26 Sep. 2007 – Myanmar government, using extreme force, cracks down on protests Blockbusters Bestall, A. – Rupert Annual 1982 Pratchett, T. – Soul Music Celery Hilden, Linda The Tortoise and the Eagle Beverly Hills Cop Goodfellas Speed Peanut Brittle Dial M for Murder Russ Abbott Arena Coast To Coast Gary Numan Live Rammstein Vast Ready to Rumble (Dreamcast) Known Nursery Rhymes 22 Nov. 1995 – Rosemary West sentenced to life imprisonment 06 Oct. 2007 – Musharraf breezes to easy re-election in Pakistan Buckaroo Bestall, A. – Rupert Annual 1984 Pratchett, T. - Sorcery Chard Hill, Debbie The Jackdaw and the Fox Beverly Hills Cop 2 The Goonies Speed 2 Pear Drops Dinnerladies The Ruth Rendell Mysteries Aretha Franklin Cochine Gene McDaniels The Living End Ramones Vegastones Resident Evil (Various) All Around the Mulberry Bush 14 Dec. 1995 – Bosnia peace accord 05 Nov. 2007 – Thousands of lawyers take to the streets to protest the state of emergency rule in Pakistan. Chess Bestall, A. – Rupert Annual 1985 Pratchett, T. – The Streets of Ankh-Morpork Chickpea Hiscock, Anna-Marie The Boy and the Wolf Bicentennial Man The Good, The Bad and the Ugly Spider Man Picnic Doctor Who The Saint Armand Van Helden Cockney Rebel Gene Pitney Lizzy Mercier Descloux Randy Crawford The Velvet Underground Robocop (Commodore 64) As I Was Going to St. Ives 02 Jan. 1996 – US Peacekeepers enter Bosnia 09 Nov. 2007 – Police barricade the city of Rawalpindi where opposition leader Benazir Bhutto plans a protest Chinese Checkers Bestall, A. – Rupert Annual 1988 Pratchett, T. -

Global Project Newsletter

July 2020 Advocating for Safe Abortion project SHARING BEST PRACTICES The Advocating for Safe Abortion project (ASAP) has just entered the 2nd year of implementation and we want to celebrate the achievements so far. It has been a year full of action that has seen all 10 member societies setting up their Project Monitoring Units (PMUs), strengthening their capacities in project management and advocacy, and beginning the implementation of their action plans. The year ended with the unexpected outbreak of COVID-19, a pandemic that has changed our ways of working and some of our plans for the future, but that has also thought us more than ever the importance of adapting our work to a constantly changing environment where women’s right to safe abortion remains a priority. This newsletter has the objective to bring the 10 countries involved in the project closer to each other and ensure that they have the opportunity to share their work and to learn from each other’s experiences. This newsletter is in no way attempting to be comprehensive and to represent all the aspects of the work done by the member societies involved, but hopefully it will bring to your attention some interesting examples of what has been done so far. Also, the way the information is presented for each society is a bit different since the best practices have been extrapolated from different activities. Some of them have been shared during the regional learning workshops in the form of Power Point presentations, and some were more extensive documents or reports. So if at any point you would like to learn more about any of the featured examples, feel free to get in touch directly with your colleagues within the relevant society. -

Bad Girls Handout Revised

STEPHANIE DRAY LILY OF THE NILE A NOVEL OF www.stephaniedray.com CLEOPATRA’S : DAUGHTER Hits Bookshelves January 2011 A survey of women’s history through the eyes of a historical fiction Bad Girls of the Ancient World novelist. HOW TO FALL AFOUL OF THE PATRIARCHY IN THREE EASY STEPS PICK UP A WEAPON Though examples of warrior women can be found in ancient literature even before the appearance of the Amazons in Homer’s tales, women who fought were considered to be unnatural. DABBLE IN PHILOSOPHY, RELIGION OR MAGIC For the ancients, religion was mostly a matter Queen Cleopatra VII, of Egypt for the state. The idea that a god of the pantheon might take a personal interest in a woman beyond seducing her or punishing her was preposterous. Consequently, priestesses were often viewed with suspicion. Alexander the Great’s mother, Olympias, was always suspected of sorcery, in part, because King Phillip fell in love with her during a religious initiation. Queen Zenobia of Palmyra Olympias of Macedonia BE SEXY Ancient man feared female sexuality and the These historical women have been painted and sway it might have over his better judgment. sculpted throughout the ages. If well-behaved The surest propaganda against an ancient women seldom make history, this should tell you queen was to depict her as a licentious seductress; a charge that has never clung with something about these ladies. more tenacity to any woman than it has to Cleopatra VII of Egypt. Copyright © 2011 Stephanie Dray, All Rights Reserved BAD GIRLS OF THE ANCIENT WORLD! PAGE2 Queen Dido commits suicide Pierre-Narcisse, baron Guérin’s painting of the famous but fictional romance between Dido and Aeneas Timeline & Relationships Dido of Carthage 800 BC Cleopatra Selene’s husband, King Dido Juba II, claimed descent from this legendary queen Queen Dido of Carthage (also Olympias of Macedonia 375 BC Alexander the Great was the son known as Elissa) was of this ambitious woman. -

“Bad Girls Changed My Life”: Homonormativity in a Women's

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Herman, Didi (2003) ”Bad Girls Changed My Life”: Homonormativity in a Women’s Prison Drama. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 20 (2). pp. 141-159. ISSN 1529-5036. DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/07393180302779 Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/1570/ Document Version UNSPECIFIED Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Kent Academic Repository – http://kar.kent.ac.uk “Bad Girls Changed My Life”: Homonormativity in a Women’s Prison Drama Didi Herman â Critical Studies in Media Communication 20 (2) pp 141 – 159 2003 Not Published Version Abstract: This paper explores representations of sexuality in a popular British television drama. The author argues that the program in question, Bad Girls, a drama set in a women’s prison, conveys a set of values that are homonormative. -

Karaoke Listing by Song Title

Karaoke Listing by Song Title Title Artiste 3 Britney Spears 11 Cassadee Pope 18 One Direction 22 Lily Allen 22 Taylor Swift 679 Fetty Wap ft Remy Boyz 1234 Feist 1973 James Blunt 1994 Jason Aldean 1999 Prince #1 Crush Garbage #thatPOWER Will.i.Am ft Justin Bieber 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay-Z & Beyonce 1 Thing Amerie 1, 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott 10,000 Nights Alphabeat 10/10 Paolo Nutini 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan & Miami Sound Machine 1-2-3 Len Barry 18 And Life Skid Row 19-2000 Gorillaz 2 Become 1 Spice Girls To Make A Request: Either hand me a completed Karaoke Request Slip or come over and let me know what song you would like to sing A full up-to-date list can be downloaded on a smart phone from www.southportdj.co.uk/karaoke-dj Karaoke Listing by Song Title Title Artiste 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue 2 Minutes To Midnight Iron Maiden 2 Pints Of Lager & A Packet Of Crisps Please Splognessabounds 2000 Miles The Pretenders 2-4-6-8 Motorway Tom Robinson Band 24K Magic Bruno Mars 3 Words (Duet Version) Cheryl Cole ft Will.I.Am 30 Days The Saturdays 30 Minute Love Affair Paloma Faith 3AM Busted 4 In The Morning Gwen Stefani 5 Colours In Her Hair McFly 5, 6, 7, 8 Steps 5-4-3-2-1 Manfred Mann 57 Chevrolet Billie Jo Spears 6 Words Wretch 32 6345 789 Blues Brothers 68 Guns The Alarm 7 Things Miley Cyrus 7 Years Lukas Graham 7/11 Beyonce 74-75 The Connells To Make A Request: Either hand me a completed Karaoke Request Slip or come over and let me know what song you would like to sing A full up-to-date list can be downloaded on a smart phone from www.southportdj.co.uk/karaoke-dj