Remarks on the Formation Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LONDON WALK No. 125 – THURSDAY 18Th JULY 2019 TRINITY BUOY WHARF & WEST INDIA DOCKS

E LONDON WALK No. 125 – THURSDAY 18th JULY 2019 TRINITY BUOY WHARF & WEST INDIA DOCKS LED BY: MARY AND IAN NICHOLSON 18 members met at Tonbridge station to catch the 9.31 train to London Bridge. We were joined by Brenda and John Boyman who had travelled from Tunbridge Wells. At London Bridge we met Carol Roberts and Pat McKay, making 22 of us for the day out. Leaving the station, we were greeted by a downpour of rain as we made a dash for our first stop which as usual was for coffee. By the time we met up again the rain had fortunately stopped. It was lovely to have Jean with us as she had been unwell and we were not sure if she would be able to come. We made our way to the underground to catch a train to Bank where we caught the DLR to take us to East India, where the walk started in earnest. The first point of interest was Meridian Point. Greenwich Prime Meridian was established by Sir George Airy in 1851. Ian asked “which side of the Meridian Line is Tonbridge?” and was given more than one answer, the correct one being west. Our group photograph was taken with everyone straddling the line and with the O2 building in the background. There was a good view across to the O2. To the left of the O2 is a steel wire sculpture created by Antony Gormley. It is called the Quantum Cloud and was completed in 1999. It is 30 metres high (taller than the Angel of the North). -

Download Directions

Getting to PKF Westferry (DLR) By Underground nk d e Li a us o Take the Jubilee line to Canary ho R A e sp im y en L r W Wharf. On leaving the station’s main r a e y f A t 12 s 61 exit, bear right onto Upper Bank e Poplar (DLR) W Hertsmere Road Street, left onto South Colonnade A1 203 and into West India Avenue. At the On top of West India Avenue, bear left tario W ay West India Quay (DLR) into Westferry Circus. rry C e ir tf c s u e s W W India N Colonnade By Docklands Ave Sq N Colonnade Cabot W Light Railway e s kr aP lP Canary Wharf e tf c e P Sq CANARY WHARF a r l r y (DLR) Canada (DLR) S Colonnade P R PIER l o l a i d h DLR to Canary Wharf S Colonnade rc u Exit the station via the double Ch Upper Bank St doors signposted “Exit to Cabot Heron Quay Canary Wharf Bank St P Place West”. Go past the shops and through the next set of double Heron doors into Cabot Square. Walk Marsh Wall Quays (DLR) through Cabot Square and into A1206 WEST INDIA DOCKS West India Avenue. At the top of West India Avenue, bear left into Westferry Circus. From the East Take the last exit to the car park By Air Approach along Aspen Way signposted Canary Riverside. Take DLR to Westferry Circus Littlejohn’s offices can the pedestrian steps at the car park following the signs to “The be accessed from all four London From the City entrance to Canary Riverside and City, Canary Wharf”. -

Explore West India Docks Little Adventures West India Docks Were the First on Your Doorstep Purpose-Built Docks to Be Built in London

Explore West India Docks Little adventures West India Docks were the first on your doorstep purpose-built docks to be built in London. Closed in 1980, the Limehouse West India Quay DLR old docks were regenerated as Northern Canary Wharf, the capital’s hi-tech Branch Dock business area. Museum of London A 126 Docklands 1 As pen Way Canary Westferry One Canada Wharf Billingsgate d Poplar Dock Road Square Market Underground a o shopping centre R s Canary ’ Wharf Pier Jubilee n o Riverboats Park t s STAY SAFE: e Middle r Stay Away From P the Edge Branch Dock Blackwall Basin Heron Wood Quays Wharf Westferry Road South Dock Wood Wharf Road River Thames West India Docks Blue Bridge Marsh Wall South Manchester Road Quay A1206 Canary Wharf Map not to scale: covers approx 0.5 miles/0.8km Isle of Dogs Millwall Inner Dock A little bit of history West India Docks were built in 1802. Here, for nearly 200 years, ships unloaded rum, sugar and coffee from the Caribbean. Cargo was loaded into warehouses, transferred on to barges and delivered all over the country via the canal system. Best of all it’s FREE!* Five things t o do Information at We st I West India Docks ndia D Spot barges and leisure river craft mooredoc ink sWest Lawn House Close India Docks. E14 9YQ Look out for the Blue Bridge which lifts up in to West Parking India Docks to allow huge ships to enter the lock. Toilets Find the old Victorian warehouses, now listed buildings, amongst the many cafés and restaurants. -

Meeting 10-16

Docklands History Group meeting Wednesday 5th November 2014 The East Country Dock By Chris Ellmers, our President Chris Ellmers, said that the East Country Dock (ECD), Rotherhithe, at the southern end of what became the Surrey Commercial Docks. He was interested in curiosities and enigmas of port history and this was a dock with very little recorded history. John Broodbank, for instance, in his monumental 1921 history of the Port of London, had only devoted half a page to it. The reason for this appears to have been the fact that the ECD archive had been previously destroyed. Around 1702 the Howland Dock (later the Greenland Dock) had opened. It was intended for the laying-up and re-fitting of East India ships, and there were also shipbuilding slips and dry docks on either side of the entrance. From the mid-1720 it was used by Greenland whalers. The estate belonged to the Russell family. Early plans and views show a rope walk to the south of the dock and beyond that the very distinctively shaped, long and narrow, Rope Walk Field. In 1763 most of the estate was sold to the Wells’ family, who were shipbuilders. The Greenland Dock continued to re-fit trading vessels and handle Greenland whalers. Later in the century some South Sea whalers were also handled there, along with grain and timber cargos. In 1803 the Wells sold the estate. By 1804, Moses Agar, an owner of East Indiamen and one of the original investors in the East India Dock Company, owned the Rope Walk field, but there is no evidence to indicate why exactly he had purchased it. -

RCHS Journal Combined Index 1955-2019

JOURNAL of the RAILWAYRAILWAY and CANALCANAL HISTORICALHISTORICAL SOCIETYSOCIETY DECENNIAL INDEX No.1No.1 Volumes I to X INTRODUCTIONINTRODUC TION The first volumevolume ofof thethe JournalJournal ofof thethe RailwayRailway andand Canal Historical SocietySociety was published inin 1955; itit consistedconsisted of fourfour issuesissues of duplicated typescript in quarto format. CommencingCommencing withwith the secondsecond volume, six issues werewere publishedpublished eacheach year until the end of thethe tenthtenth volume,volume, after which thethe Journal was published asas aa prinprin- ted quarterly. AA slight slight change change in in the the method method of of reproduction reproduction was was introducedintroduced withwith volume IX; thisthis and thethe succeeding volumevolume werewere producedproduced byby offset-lithooffset-litho process.process. The first fourfour volumesvolumes included notnot onlyonly original original articles,articles, compilations,compilations, book reviewsreviews and correspondence,correspondence, but also materialmaterial concerned concerned with with thethe day-to-dayday-to-day running of thethe Society,Society, suchsuch as announcementsannouncements of forthcoming events,events, accountsaccounts of meetings andand visits,visits, listslists of of new new membersmembers andand the like. CommencingCommencing withwith volume V,V, all such material waswas transferred to to a a new new andand separateseparate monthly monthly pub-pub lication, thethe R.R. di& C.C.H.S. H. S. Bulletin, aa practicepractice which which hashas continuedcontinued to the present time. The purpose of the present publicationpublication is toto provideprovide aa comprehensivecomprehensive andand detailed Index toto allall thethe originaloriginal material in the first tenten volumesvolumes ofof the Society'sSociety's JournallikelJournal likely y to be of interestinterest toto thethe canalcanal oror railwayrailway historian historian or or student.student. -

NQ.PA.15. Heritage Assessment – July 2020

NQ.PA.15 NQ.LBC.03 North Quay Heritage Assessment Peter Stewart Consultancy July 2020 North Quay – Heritage Assessment Contents Executive Summary 1 1 Introduction 3 2 Heritage planning policy and guidance 7 3 The Site and its heritage context 15 4 Assessment of effect of proposals 34 5 Conclusion 41 Appendix 1 Abbreviations 43 July 2020 | 1 North Quay – Heritage Assessment Executive Summary This Heritage Assessment has been prepared in support of the application proposals for the Site, which is located in Canary Wharf, in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets (”LBTH”). The assessment considers the effect of the Proposed Development in the context of heritage legislation and policy on a number of designated heritage assets, all of which are less than 500m from the boundary of the Site. These designated heritage assets have been identified as those which could be potentially affected, in terms of their ‘significance’ as defined in the NPPF, as a result of development on the Site. It should be read in conjunction with the Built Heritage Assessment (“BHA”), which assesses the effect of the Proposed Development on the setting of heritage assets in the wider area, and the Townscape and visual impact assessment (“TVIA”), both within the Environmental Statement Volume II (ref NQ.PA.08 Vol. 2), also prepared by Peter Stewart Consultancy. A section of the grade I listed Dock wall runs below ground through the Site. This aspect of the project is assessed in detail in the Archaeological Desk Based Assessment accompanying the outline planning application and LBC (ref. NQ.PA.26/ NQ.LBC.07) and the Outline Sequence of Works for Banana Wall Listed Building Consent report (ref. -

London's Infrastructure of Import

09 Difference and the Docklands: London’s Infrastructure of Import Elizabeth Bishop 56 By the beginning of the 19th century the British Empire had Elihu Yale, hailed as the founder of Yale University after his donation of West India Docks, were not employed until the mid-to-late 18th century, when “… the tide of commerce—the 57 been embracing contact with difference from overseas for some time. valuable East India goods to Cotton Mather, was one such servant of the life-stream of the capital—began to leave, so to speak, an architectural deposit in its course.”9 Along with the The Empire had grown to include an array of colonies and dependen- East India Company. Yale, then governor of Madras, employed a variety external forces of trade, the increasing chaos of the port itself enacted change on the city.10 Shipping traffic cies and British culture, especially in London, had enjoyed imports of questionable administrative techniques that eventually caused him crowded into the port, including the merchant ships (known as East and West Indiamen), the coal colliers 01 from these territories for years. No longer did England rely on entrepôt to step down from his post and retire to London.5 that traveled between London and other British ports, and lighters, the smaller, flat-bottomed boats used to cities such as Amsterdam and Venice. By 1800 the British Empire had unload the larger ships. In addition to this increased traffic, the Thames was difficult to navigate because of “An elevated view of the West India Docks” (1800), strengthened its naval forces and developed its own import and export As similar as the two major companies were, there were some its tidal nature. -

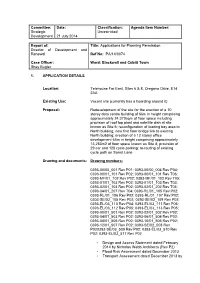

Report Of: Title: Applications for Planning Permission Director of Development and Renewal Ref No: PA/14/0074

Committee: Date: Classification: Agenda Item Number: Strategic Unrestricted Development 21 July 2014 Report of: Title: Applications for Planning Permission Director of Development and Renewal Ref No: PA/14/0074 Case Officer: Ward: Blackwall and Cubitt Town Shay Bugler 1. APPLICATION DETAILS Location: Telehouse Far East, Sites 6 & 8, Oregano Drive, E14 2AA Existing Use: Vacant site (currently has a hoarding around it) Proposal: Redevelopment of the site for the erection of a 10 storey data centre building of 66m in height comprising approximately 24,370sqm of floor space including provision of roof top plant and satellite dish at site known as Site 6; reconfiguration of loading bay area to North building; new first floor bridge link to existing North building; erection of a 12 storey office development 65m in height comprising approximately 13,283m2 of floor space known as Site 8; provision of 29 car and 128 cycle parking; re-routing of existing cycle path on Sorrel Lane. Drawing and documents: Drawing numbers: 0393-00/00_001 Rev P01; 0393-00/00_004 Rev P04; 0393-00/01_101 Rev P02; 0393-00/01_101 Rev T06; 0393-MF/01_102 Rev P02; 0393-MF/01_102 Rev T05; 0393-01/01_103 Rev P02; 0393-01/01_103 Rev T03; 0393-02/01_104 Rev P02; 0393-02/01_202 Rev T04; 0393-04/01_207 Rev T04; 0393-RL/01_105 Rev P02; 0393-RL/01_106 Rev P02; 0393-RL/01_107 Rev P02; 0303-SE/02_108 Rev P02; 0393-SE/02_109 Rev P02; 0393-EL/03_110 Rev P04; 0393-EL/03_111 Rev P05; 0393-EL/03_112 Rev P05; 0393-EL/03_113 Rev P05; 0393-00/01_501 Rev P02; 0393-02/01_502 Rev P02; 0393-04/01_503 -

North Quay Archaeological Desk Based Assessment

NQ.PA.26 NQ.LBC.07 North Quay Archaeological Desk Based Assessment RPS July 2020 ARCHAEOLOGICAL DESK BASED ASSESSMENT Executive Summary Canary Wharf (North Quay) Ltd (“the Applicant”) are submitting applications for Outline Planning Permission (OPP) and Listed Building Consent (LBC) to enable the redevelopment of the North Quay site, Aspen Way, London (“the Site”). Two separate applications are being submitted for the works. The applications will seek permission for: • Application NQ.1: Outline Planning Application (all matters reserved) (“OPA”) - Application for the mixed-use redevelopment of the Site comprising demolition of existing buildings and structures and the erection of buildings comprising business floorspace, hotel/serviced apartments, residential, co- living, student housing, retail, community and leisure and sui generis uses with associated infrastructure, parking and servicing space, public realm, highways and access works; and • Application NQ.2: Listed Building Consent (“LBCA”) - Application to stabilise listed quay wall and any associated/necessary remedial works as well as demolition of the false quay in connection with Application NQ.1. The study site lies within the Isle of Dogs Tier 3 Lea Valley Archaeological Priority Area associated with palaeoenvironmental evidence for past wetland and riverine environments and potential for prehistoric remains. It was also an extensive area of historic industry and trade in the 19th and 20th centuries. A Grade I Listed heritage asset (‘Banana’ Dock Wall) survives buried within the site. The proposed development has been designed to preserve in situ the remains of the Grade I Listed Banana Wall. Consequently, there will be no adverse impact to this designated heritage asset from the proposed development. -

DLR YEARS30 of EXCELLENCE This Celebration of 30 Years of the Docklands Light Railway Is Produced in Association with Tramways & Urban Transit © 2017

A special focus in association with DLR YEARS30 OF EXCELLENCE This celebration of 30 years of the Docklands Light Railway is produced in association with Tramways & Urban Transit © 2017 Supplement Editor: Neil Pulling Design: Debbie Nolan Production: Lanna Blyth Commercial: Geoff Butler TAUT Editor: Simon Johnston Inside back cover images courtesy of Express Photo Services/KeolisAmey Docklands; all other images by Neil Pulling unless otherwise stated. With thanks to the staff of Docklands Light Railway Limited and KeolisAmey Docklands, in particular: Faisal Ahmed, David Arquati, Abdellah Chajai, Dave Collins, Mark Davis, Clare Donovan, Anna Hirst, Sara Kent, Bridget Lawrence, Jon Miller, Geoff Mitchell, Rob Niven, Danny Price, Kevin Thomas, Mike Turner and David West. LOOKING FORWARD, LOOKING BACK n 1987, the Docklands Light Railway (DLR) Above: TfL’s DLR performing teams work to deliver service excellence opened for service in east London. Upgrade Plan every day, and our Community Ambassadors work I This automated, driverless railway has been contemplates the effects with local communities and help people to get around at the heart of the development of the Docklands area on demand of future on the DLR. From arranging accessibility trips, holding for 30 years. Kick-starting the regeneration of the ‘Manhattan densities’ open days in community centres and supermarkets, area, the railway has been the transport backbone for around South Quay. through to attending local events, coffee mornings east London communities and has been integral to and forums to give travel advice and answer the continuing increase in both residential and questions, they play an important role in bringing commercial populations within the Docklands. -

Docklands History Group Meeting Wednesday 1St August 2007 London Locks, Docks, and Marinas by Jeremy Batch

Docklands History Group meeting Wednesday 1st August 2007 London Locks, Docks, and Marinas By Jeremy Batch Jeremy gave us a very interesting whistle stop tour through the history of the area from BC up to date. He started with the effects of war and Roman invaders defeating the Belgae, despite fierce resistance. The Romans then built London Bridge. He made the point that there was not a tide of 20 feet in those days where the bridge was sited. Some bridge remains had been found when the Jubilee Line Station near London Bridge had been excavated. In 410 AD the legions withdrew, but not all the Romans. In 890 the Danes raided up the Lee to Hertford, sacked it and built a fort. At Ware King Alfred built a dam and diverted the river to maroon their ships. In 984 in China, Qiao Weiyue had a problem, grain barges were being raided and the Emperor was unhappy. He did what many men do in times of crises, he built a shed. This shed was the first pound lock. In 1016 when Cnut raided up the Thames and found his way blocked by London Bridge, he did what another invader would do 900 years later when faced with the impregnable Maginot Line, he went round it. The Vikings did this by digging a channel to the south. The channel was subsequently used as a diversion for the river water when London Bridge was re-built. In 1076 the White Tower was built by the Normans and in 1150 Queen Matilda established a Hospital on a tidal inlet, which was known as the Royal Foundation of St Katharine by the Tower. -

Chronicles of Blackwall Yard

^^^VlBEDi^,^ %»*i?' ^^ PART • 1 University of Calil Southern Regioi Library Facility^ £x Libris C. K. OGDEN ^^i^-^-i^^ / /st^ , ^ ^ THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES CHRONICLES OF BLACKWALL YARD PART I. BY HENRY GREEN and ROBERT WIGRAM. " Nos .... nee gravem Pelidcc stomaclium, cedere nescii. Nee ciirsus diiplicU per mare U/ixei, Nee sava»i Pelopis domiim Coiiannir, teniies grandia ; . " Hor., Lib. I.. Car. IV. PUBLISHED BY WHITEHEAD, MORRIS AND LOWE. lS8l. 2>0l @^ronicIc6 of '^iackxxxxii ^ar6. AT the time when our Chronicles commence, the Hamlet of Poplar and Blackwall, in which the dockyard whose history we propose to sketch is situated, was, together with the Hamlets of Ratclifie and Mile End, included in the old Parish of Stebunhethe, now Stepney, in the hundred of Ossulston. The Manor of Stebunhethe is stated in 1067. the Survey of Doomsday to have been parcel of the ancient demesnes of the Bishopric of London. It is there described as of large extent, 1299. and valued at ^48 per annum! In the year 1299 a Parliament was held Lyson's En- by King Edward I., at Stebunhethe, in the house of Henry Walleis, virons^ Mayor of London, when that monarch confirmed the charter of liberties. p. 678. Stebunhethe Marsh adjoining to Blackwall, which was subsequently called Stows but the Isle of years after this Annals. the South Marsh, now Dogs, was some described as a tract of land lying within the curve the P- 319- which Thames forms between Ratcliffe and Blackwall. Continual reference is made in local records to the embankments of this marsh, and to the frequent 1307- breaches in them.