The Regeneration of London's Docklands: New Riverside

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rotherhithe Cycleway Consultation • Southwark.Gov.Uk • Page 01 Rotherhithe Cycleway Consultation

APPENDIX B Rotherhithe Cycleway consultation • southwark.gov.uk • Page 01 Rotherhithe Cycleway consultation Summary Report November 2019 Rotherhithe Cycleway consultation • southwark.gov.uk • Page 02 How we consulted What was consulted? This report summarises the consultation feedback for the The distribution area was large enough to gain views Rotherhithe Cycleway which links Cycleway 4 and from the wider community that may be considered to be Quietway 14 as a first phase and we are exploring affected by the proposed measures. A copy of the potential connections towards Peckham. The proposals postcards is appended. are located in Rotherhithe and Surrey Docks Wards. Consultees were invited to attend drop in sessions as Future cycling demand is predicting there will be a listed below and advised to respond to the consultation significant desire to\from Peckham and beyond, with up via the online consultation portal. They were also given to 150 cyclists using this section of the route during the an email address and telephone number by which to peak period, in the event of a free ferry crossing being respond: developed. a. 23 Jul 2019 at 17:30 to 20:00 at Canada Water The proposals include: Library b. 8 Aug 2019 at 18:00 to 20:00 at Osprey Estate a. Existing roundabouts at Redriff Road junctions TRA Hall with Surrey Quays Road and Quebec Way c. 30 Aug 2019 at 12:00 to 18:00 at Canada Water replaced with traffic signals with pedestrian Library crossings on each arm of the junction d. 7 Sep 2019 at 12:00 to 18:00 at Bacon's College b. -

Residential Update

Residential update UK Residential Research | January 2018 South East London has benefitted from a significant facelift in recent years. A number of regeneration projects, including the redevelopment of ex-council estates, has not only transformed the local area, but has attracted in other developers. More affordable pricing compared with many other locations in London has also played its part. The prospects for South East London are bright, with plenty of residential developments raising the bar even further whilst also providing a more diverse choice for residents. Regeneration catalyst Pricing attraction Facelift boosts outlook South East London is a hive of residential Pricing has been critical in the residential The outlook for South East London is development activity. Almost 5,000 revolution in South East London. also bright. new private residential units are under Indeed pricing is so competitive relative While several of the major regeneration construction. There are also over 29,000 to many other parts of the capital, projects are completed or nearly private units in the planning pipeline or especially compared with north of the river, completed there are still others to come. unbuilt in existing developments, making it has meant that the residential product For example, Convoys Wharf has the it one of London’s most active residential developed has appealed to both residents potential to deliver around 3,500 homes development regions. within the area as well as people from and British Land plan to develop a similar Large regeneration projects are playing further afield. number at Canada Water. a key role in the delivery of much needed The competitively-priced Lewisham is But given the facelift that has already housing but are also vital in the uprating a prime example of where people have taken place and the enhanced perception and gentrification of many parts of moved within South East London to a more of South East London as a desirable and South East London. -

Witness Statement of Stuart Sherbrooke Wortley Dated April 2021 Urbex Activity Since 21 September 2020

Party: Claimant Witness: SS Wortley Statement: First Exhibits: “SSW1” - “SSW7” Date: 27.04.21 Claim Number: IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE QUEEN’S BENCH DIVISION B E T W E E N (1) MULTIPLEX CONSTRUCTION EUROPE LIMITED (2) 30 GS NOMINEE 1 LIMITED (3) 30 GS NOMINEE 2 LIMITED Claimants and PERSONS UNKNOWN ENTERING IN OR REMAINING AT THE 30 GROSVENOR SQUARE CONSTRUCTION SITE WITHOUT THE CLAIMANTS’ PERMISSION Defendants ______________________________________ WITNESS STATEMENT OF STUART SHERBROOKE WORTLEY ________________________________________ I, STUART SHERBROOKE WORTLEY of One Wood Street, London, EC2V 7WS WILL SAY as follows:- 1. I am a partner of Eversheds Sutherland LLP, solicitors for the Claimants. 2. I make this witness statement in support of the Claimants’ application for an injunction to prevent the Defendants from trespassing on the 30 Grosvenor Square Construction Site (as defined in the Particulars of Claim). cam_1b\7357799\3 1 3. Where the facts referred to in this witness statement are within my own knowledge they are true; where the facts are not within my own knowledge, I believe them to be true and I have provided the source of my information. 4. I have read a copy of the witness statement of Martin Philip Wilshire. 5. In this witness statement, I provide the following evidence:- 5.1 in paragraphs 8-21, some recent videos and photographs of incidents of trespass uploaded to social media by urban explorers at construction sites in London; 5.2 in paragraphs 22-27, information concerning injunctions which my team has obtained -

Worthington Steel

Worthington Steel (Division of Worthington Industries) Historical Load Volume March - May, 2002 Carrier Weekly Estimated Truck ORIGIN DESTINATION DST Historical Load Volume Capacity BALTIMORE DECATUR AL 8 BALTIMORE BRISTOL CT 2 BALTIMORE FARMINGTON CT 1 BALTIMORE PLANTSVILLE CT 2 BALTIMORE SOUTHINGTON CT 7 BALTIMORE THOMASTON CT 5 BALTIMORE WATERBURY CT 6 BALTIMORE WATERTOWN CT 3 BALTIMORE WEST HAVEN CT 2 BALTIMORE WINSTED CT 2 BALTIMORE DOVER DE 1 BALTIMORE CARTERSVILLE GA 2 BALTIMORE COLUMBUS GA 1 BALTIMORE LAWRENCEVILL GA 1 BALTIMORE ROME GA 4 BALTIMORE ROYSTON GA 2 BALTIMORE ELK GROVE IL 3 BALTIMORE FRANKLIN IL 2 BALTIMORE FORT WAYNE IN 2 BALTIMORE GREENFIELD IN 0 BALTIMORE PORTER IN 1 BALTIMORE LOUISVILLE KY 2 BALTIMORE ATTLEBORO MA 3 BALTIMORE EAST MA 16 BALTIMORE FITCHBURG MA 1 BALTIMORE GARDNER MA 3 BALTIMORE S. ATTLEBORO MA 4 BALTIMORE SOUTH MA 4 BALTIMORE SOUTHWICK MA 2 BALTIMORE WORCESTER MA 26 BALTIMORE BALTIMORE MD 58 BALTIMORE COCKEYSVILLE MD 1 BALTIMORE CUMBERLAND MD 2 BALTIMORE HAMSTEAD MD 15 BALTIMORE JESSUP MD 29 BALTIMORE SEVERN MD 1 BALTIMORE SPARROWS MD 173 BALTIMORE TANEYTOWN MD 18 BALTIMORE WEST MD 35 BALTIMORE WESTMINISTER MD 6 BALTIMORE WESTMINSTER MD 56 BALTIMORE JACKSON MI 2 BALTIMORE KENTWOOD MI 5 BALTIMORE MONROE MI 3 BALTIMORE DENTON NC 2 Worthington Steel (Division of Worthington Industries) Historical Load Volume March - May, 2002 Carrier Weekly Estimated Truck ORIGIN DESTINATION DST Historical Load Volume Capacity BALTIMORE GASTONIA NC 23 BALTIMORE HAMILTON NC 4 BALTIMORE HIGH POINT NC 12 BALTIMORE NEWTON -

LONDON WALK No. 125 – THURSDAY 18Th JULY 2019 TRINITY BUOY WHARF & WEST INDIA DOCKS

E LONDON WALK No. 125 – THURSDAY 18th JULY 2019 TRINITY BUOY WHARF & WEST INDIA DOCKS LED BY: MARY AND IAN NICHOLSON 18 members met at Tonbridge station to catch the 9.31 train to London Bridge. We were joined by Brenda and John Boyman who had travelled from Tunbridge Wells. At London Bridge we met Carol Roberts and Pat McKay, making 22 of us for the day out. Leaving the station, we were greeted by a downpour of rain as we made a dash for our first stop which as usual was for coffee. By the time we met up again the rain had fortunately stopped. It was lovely to have Jean with us as she had been unwell and we were not sure if she would be able to come. We made our way to the underground to catch a train to Bank where we caught the DLR to take us to East India, where the walk started in earnest. The first point of interest was Meridian Point. Greenwich Prime Meridian was established by Sir George Airy in 1851. Ian asked “which side of the Meridian Line is Tonbridge?” and was given more than one answer, the correct one being west. Our group photograph was taken with everyone straddling the line and with the O2 building in the background. There was a good view across to the O2. To the left of the O2 is a steel wire sculpture created by Antony Gormley. It is called the Quantum Cloud and was completed in 1999. It is 30 metres high (taller than the Angel of the North). -

Outer East London

A Broad Rental Market Area is an area ‘within which a person could reasonably be expected to live having regard to facilities and services for the purposes of health, education, recreation, personal banking and shopping, taking account of the distance of travel, by public and private transport, to and from those facilities and services.’ A BRMA must contain ‘residential premises of a variety of types, including such premises held on a variety of tenures’, plus ‘sufficient privately rented residential premises, to ensure that, in the rent officer’s opinion, the LHA for the area is representative of the rents that a landlord might reasonably be expected to obtain in that area’. [Legislation - Rent Officers (Housing Benefit Functions) Amendment (No.2) Order 2008] OUTER EAST LONDON Broad Rental Market Area (BRMA) implemented on 1st October 2009 Map of the BRMA Overview of the BRMA The above map shows Stratford, Walthamstow, Leyton, West Ham, East Ham and their surroundings within a boundary marked in red. Predominantly residential, the BRMA measures approximately nine miles from north to south and about four miles from east to west. As Stratford will host the Olympic Games in 2012, investment is currently underway to bring commercial, employment and transport improvements to the area. Docklands is located further south and contains City Airport and the Excel Centre. Docklands is a business district of significance and of importance for the country as a whole. This BRMA is situated in Transport for London Zone 3. Public transport is plentiful with four underground lines connecting in all directions, supplemented by an overground rail system connecting Walthamstow to Stratford and then eastwards towards Leytonstone. -

List of Accessible Overground Stations Grouped by Overground Line

List of Accessible Overground Stations Grouped by Overground Line Legend: Page | 1 = Step-free access street to platform = Step-free access street to train This information was correct at time of publication. Please check Transport for London for further information regarding station access. This list was compiled by Benjamin Holt, Transport for All 29/05/2019. Canada Water Step-free access street to train East London line Haggerston Step-free access street to platform Dalston Hoxton Step-free access street to platform Junction - New New Cross Step-free access street to platform Cross Canada Water Step-free access street to platform Clapham High Street Step-free access street to platform Denmark Hill Step-free access street to platform Haggerston Step-free access street to platform Hoxton Step-free access street to platform Peckham Rye Step-free access street to platform Queens Road Peckham Step-free access street to platform East London line Rotherhithe Step-free access street to platform Shadwell Step-free access street to platform Dalston Canada Water Step-free access street to train Junction - Canonbury Step-free access street to train Clapham Crystal Palace Step-free access street to platform Junction Dalston Junction Step-free access street to train Forest Hill Step-free access street to platform Haggerston Step-free access street to train Highbury & Islington Step-free access street to platform Honor Oak Park Step-free access street to platform Hoxton Step-free access street to train New Cross Gate Step-free access street to platform -

THOMSON REUTERS MAP.Ai

PUBLIC TRANSPORT PUBLIC TRANSPORT Watford M Hatfield A1 2 LIMEHOUSE DOCKLAND 1 M25 1 DLR 1 N TRAIN STATION LIGHT RAILWAY M Hendon A1 27 Situated on Commercial Road Canary Wharf Station. Situated High A406 (A13), walk to the Limehouse at the centre of North and South Wycombe Basildon The Thomson Reuters Building M 2 DLR Station and catch a Colonnade. The Station is a two M4 5 South Colonnade 0 A40 A1 3 connecting train to Canary minute walk from our building. A1 3 Slough Canary Wharf Wharf. CITY OF • London C ity LONDON Airport London M4 Tilbury LONDON CITY LONDON UNDERGROUND • A20 5 2 E14 5ep CANARY WHARF • AIRPORT Heathrow A205 M Airport Jubilee Line Extention – links Catch a connecting London Gravesend A3 Croydon Canary Wharf with Waterloo City Airport shuttle bus to SECTION M 2 +44 (0)20 7250 1122 0 Station and London Bridge, Canary Wharf DETAILED M3 BELOW M25 thomsonreuters.com also other tube lines. Wok ing Limehouse MANOR Train Station A Docklands B BURDETT 1 ROAD 1 0 A1 206 2 ROAD Blackwell Tunnel 2 Isle of Dogs 1 Dover A1 02 N C anary Wharf WESTFERRY C IRC US (A1 3) Folkestone COMMERCIAL Royal Docks ROAD C ity 3 C anary A1 Wharf Airport C . London A1 3 One Way COMMERCIAL EAST INDIA ROAD C abot Square DOCK ROAD A1 3 L I M E H O U S E P P C anary Wharf Start here DLR A1 3 A1 3 From the East To Tower Gateway A L L (A1 3) & Central London 6 S A I N T S 0 2 1 P O P L A R Start here W E S T F E R R Y A C . -

YPG2EL Newspaper

THE YOUNG PERSON’S GUIDE TO EAST LONDON East London places they don’t put in travel guides! Recipient of a Media Trust Community Voices award A BIG THANK YOU TO OUR SPONSORS This organisation has been awarded a Transformers grant, funded by the National Lottery through the Olympic Lottery Distributor and managed by ELBA Café Verde @ Riverside > The Mosaic, 45 Narrow Street, Limehouse, London E14 8DN > Fresh food, authentic Italian menu, nice surroundings – a good place to hang out, sit with an ice cream and watch the fountain. For the full review and travel information go to page 5. great places to visit in East London reviewed by the EY ETCH FO P UN K D C A JA T I E O H N Discover T B 9 teenagers who live there. In this guide you’ll find reviews, A C 9 K 9 1 I N E G C N YO I U E S travel information and photos of over 200 places to visit, NG PEOPL all within the five London 2012 Olympic boroughs. WWW.YPG2EL.ORG Young Persons Guide to East London 3 About the Project How to use the guide ind an East London that won’t be All sites are listed A-Z order. Each place entry in the travel guides. This guide begins with the areas of interest to which it F will take you to the places most relates: visited by East London teenagers, whether Arts and Culture, Beckton District Park South to eat, shop, play or just hang out. Hanging Out, Parks, clubs, sport, arts and music Great Views, venues, mosques, temples and churches, Sport, Let’s youth centres, markets, places of history Shop, Transport, and heritage are all here. -

CANADA WATER Issue 01 | Spring 2016

CANADA WATER Issue 01 | Spring 2016 Canada Water Decathlon leads Seeding the future Masterplan the pack Rural pursuits for young Have your say on the Designing a new people in the heart plans that will shape town centre of the city the developments VOX POPS FOREWORD 02 03 MY CANADA WATER Locals tell us what they Cllr Mark Williams Cabinet member for love about Canada Water regeneration and new homes Dominika I love this area as you are in a city but it doesn’t feel like a city. I grew up in the countryside in Poland so I like to be near nature and here there are so many lovely green spaces. I like photography and take photos of the birds and flowers and trees. Welcome to the first edition of the the future. It is crucial that we hear It’s also nice living so close to the river. Josue Phaik Canada Water magazine which your thoughts as local residents It is very relaxing and it’s great to be Over the years I have seen lots of The library is my favourite place. I was celebrates the rich history and hidden on the emerging plans and there able to get the boat to Canary Wharf. changes and it has created a different eager to see how they were going to treasures of the local area, while is information on how you can get and better vibe. More communities do it and it’s excellent. The shape is also looking at the opportunities the involved in the discussions and plans are exposed to each other and are unique and the interior is good as future holds. -

Buses from Bromley-By-Bow and Devons Road

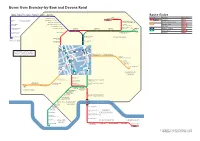

Buses from Bromley-by-Bow and Devons Road Homerton Brooksbys Walk Kenworthy Hackney Wick Hackney Monier Road Hospital Homerton Road Eastway Wick Wansbeck Road Route finder Bus route Towards Bus stops Jodrell Road Wick Lane Stratford International Á Â Clapton Parnell Road Waterside Close 108 108 Lewisham Pond HACKNEY Stratford City Bus Station Parnell Road Old Ford Road for Stratford Stratford International » ½ Hackney Downs Parnell Road Roman Road Market Pool Street 323 Canning Town · ¸ ¹ Downs Road London Aquatics Centre Fairfield Road Tredegar Road Mile End ³ µ ¶ Carpenters Road Kingsland High Street Fairfield Road Bow Bus Garage Bow Road High Street High Street Gibbins Road 488 Dalston Junction ¬ ° Shacklewell Lane Bow Church Marshgate Lane Warton Road Stratford Bus Station D8 Crossharbour ¬ ® Stratford High Street D8 Dalston Kingsland Bow Church Carpenters Road Stratford ¯ ° Bromley High Street Dalston Junction Bow Interchange 488 Campbell Road STRATFORD Bow Road DALSTON St. Leonards Street Campbell Road Grace Street Rounton Road D R K EET C STR O N C LWI N TA HA AY BL ILL W Bromley-by-Bow NH AC RAI K C WA The yellow tinted area includes every bus P A DE ° UR M ROU R stop up to about one-and-a-half miles from V L EEV ¬ P D L TU ONS RD Bromley-by-Bow and Devons Road. Main B Y S NTON E E Twelvetrees Crescent Twelvetrees Crescent L S T N stops are shown in the white area outside. L R ¹ ProLogis Park Crown Records Building REET D NEL N R School O REET D A ¸ S ST A ³ Cody Road D ON R DEV T SWA ROA ½ Á School O North Crescent Business Centre R T µ H D G ER I ET LL Devons N STRE ¯ SO APPR N Star Lane EMP EN Road RD D S D P E T RD Manor Road . -

Days out on a Budget

Days Out on a Budget Royal Greenwich Families Information Service. Tel: 020 8921 6921 Email: [email protected] 1 This listing provides some ideas of places to visit within the local area and central London with your child(ren). We have selected places that are free or low cost. This is a developing list and we would be pleased to receive details of any other places or activities you can recommend. Please contact us, tel. 020 8921 6921, email [email protected]. Please note that this information is correct at time of print but is liable to change at any time. With regards Royal Greenwich Families Information Service Contents Museums & galleries Pages 3 – 9 Local venues 3-4 Venues around London 5-9 Parks, gardens & farms 10 – 18 Local venues 10-14 Venues around London 15-18 Visit the woods 19 Other 20 Travel information 20 Royal Greenwich Families Information Service. Tel: 020 8921 6921 Email: [email protected] 2 Museums & Galleries – Local Venues Firepower The Royal Artillery Museum, Royal Arsenal, Woolwich, SE18 6ST. Tel. 020 8855 7755 Email: [email protected]; Web: www.firepower.org.uk Price: Adult £5.30 / Child £2.50 / Concessions £4.60 (ES40, Seniors 60+; Students – ID required) Inclusive child admission during holidays - access to all activities £6.50. Tuesday-Saturday: 10am-5pm, last admission 4pm. Closed Sunday & Monday Buses: 177, 180, 472, 161, 96, 99, 469, 51, 54 / Rail/DLR: Woolwich Arsenal The Museum offers an insight into artillery and the role that the Gunners and their equipment have played in our Nation’s History.