The Crystal Palace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (2399Kb)

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/ 84893 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications Culture is a Weapon: Popular Music, Protest and Opposition to Apartheid in Britain David Toulson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History University of Warwick Department of History January 2016 Table of Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………...iv Declaration………………………………………………………………………….v Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….vi Introduction………………………………………………………………………..1 ‘A rock concert with a cause’……………………………………………………….1 Come Together……………………………………………………………………...7 Methodology………………………………………………………………………13 Research Questions and Structure…………………………………………………22 1)“Culture is a weapon that we can use against the apartheid regime”……...25 The Cultural Boycott and the Anti-Apartheid Movement…………………………25 ‘The Times They Are A Changing’………………………………………………..34 ‘Culture is a weapon of struggle’………………………………………………….47 Rock Against Racism……………………………………………………………...54 ‘We need less airy fairy freedom music and more action.’………………………..72 2) ‘The Myth -

The Potential for Urban Logistics Hubs in Central London

Final report December 2020 The Potential for Urban Logistics Hubs in Central London Steer has prepared this material for Cross River Partnership. This material may only be used within the context and scope for which Steer has prepared it and may not be relied upon in part or whole by any third party or be used for any other purpose. Any person choosing to use any part of this material without the express and written permission of Steer shall be deemed to confirm their agreement to indemnify Steer for all loss or damage resulting therefrom. Steer has prepared this material using professional practices and procedures using information available to it at the time and as such any new information could alter the validity of the results and conclusions made. The Potential for Urban Logistics Hubs in Central London Prepared by: Prepared for: Steer Cross River Partnership 28-32 Upper Ground Westminster City Hall London SE1 9PD 64 Victoria Street LondonSW1E 6QP +44 20 7910 5000 www.steergroup.com 23957801 Click here to enter text. Steer has prepared this material for Cross River Partnership. This material may only be used within the context and scope for which Steer has prepared it and may not be relied upon in part or whole by any third party or be used for any other purpose. Any person choosing to use any part of this material without the express and written permission of Steer shall be deemed to confirm their agreement to indemnify Steer for all loss or damage resulting therefrom. Steer has prepared this material using professional practices and procedures using information available to it at the time and as such any new information could alter the validity of the results and conclusions made. -

Key Bus Routes in Central London

Route 8 Route 9 Key bus routes in central London 24 88 390 43 to Stoke Newington Route 11 to Hampstead Heath to Parliament to to 73 Route 14 Hill Fields Archway Friern Camden Lock 38 Route 15 139 to Golders Green ZSL Market Barnet London Zoo Route 23 23 to Clapton Westbourne Park Abbey Road Camden York Way Caledonian Pond Route 24 ZSL Camden Town Agar Grove Lord’s Cricket London Road Road & Route 25 Ground Zoo Barnsbury Essex Road Route 38 Ladbroke Grove Lisson Grove Albany Street Sainsbury’s for ZSL London Zoo Islington Angel Route 43 Sherlock Mornington London Crescent Route 59 Holmes Regent’s Park Canal to Bow 8 Museum Museum 274 Route 73 Ladbroke Grove Madame Tussauds Route 74 King’s St. John Old Street Street Telecom Euston Cross Sadler’s Wells Route 88 205 Marylebone Tower Theatre Route 139 Charles Dickens Paddington Shoreditch Route 148 Great Warren Street St. Pancras Museum High Street 453 74 Baker Regent’s Portland and 59 International Barbican Route 159 Street Park Centre Liverpool St Street Euston Square (390 only) Route 188 Moorgate Appold Street Edgware Road 11 Route 205 Pollock’s 14 188 Theobald’s Toy Museum Russell Road Route 274 Square British Museum Route 390 Goodge Street of London Museum Liverpool St Route 453 Marble Lancaster Arch Bloomsbury Way Bank Notting Hill 25 Gate Gate Bond Oxford Holborn Chancery 25 to Ilford Queensway Tottenham 8 148 274 Street 159 Circus Court Road/ Lane Holborn St. 205 to Bow 73 Viaduct Paul’s to Shepherd’s Marble Cambridge Hyde Arch for City Bush/ Park Circus Thameslink White City Kensington Regent Street Aldgate (night Park Lane Eros journeys Gardens Covent Garden Market 15 only) Albert Shaftesbury to Blackwall Memorial Avenue Kingsway to Royal Tower Hammersmith Academy Nelson’s Leicester Cannon Hill 9 Royal Column Piccadilly Circus Square Street Monument 23 Albert Hall Knightsbridge London St. -

Core Strategy

APPENDIX 2 AREA PEN PORTRAITS 1 Beckenham Copers Cope & Kangley Bridge 2 Bickley 3 Bromley Common 4 Chislehurst 5 Clock House, Elmers End & Eden Park 6 Cray Valley, St Paul's Cray & St. Mary Cray 7 Crofton and Farnborough 8 Crystal Palace, Penge & Anerley 9 Hayes 10 Keston 11 Mottingham 12 Shortlands, Park Langley & Pickhurst 13 West Wickham & Coney Hall Places within the London Borough of Bromley Ravensbourne, Plaistow & Sundridge Mottingham Beckenham Copers Cope Bromley Bickley & Kangley Bridge Town Chislehurst Crystal Palace Cray Valley, St Paul's Penge and Anerley Cray & St. Mary Cray Shortlands, Park Eastern Green Belt Langley & Pickhurst Clock House, Elmers Petts Wood & Poverest End & Eden Park Orpington, Ramsden West Wickham & Coney Hall & Goddington Hayes Crofton & Farnborough Bromley Common Chelsfield, Green Street Green & Pratts Bottom Keston Darwin & Green Belt Biggin Hill Settlements Reproduced by permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of HMSO. © Crown copyright and database 2011. Ordnance Survey Licence number 100017661. BECKENHAM COPERS COPE & KANGLEY BRIDGE Character The introduction of the railway in mid-Victorian times saw Beckenham develop from a small village into a town on the edge of suburbia. The majority of dwellings in the area are Victorian with some 1940’s and 50’s flats and houses. On the whole houses tend to have fair sized gardens; however, where there are smaller dwellings and flatted developments there is a lack of available off-street parking. During the later part of the 20th century a significant number of Victorian villas were converted or replaced by modern blocks of flats or housing. Ten conservation areas have been established to help preserve and enhance the appearance of the area reflecting the historic character of the area. -

Walks Programme: July to September 2021

LONDON STROLLERS WALKS PROGRAMME: JULY TO SEPTEMBER 2021 NOTES AND ANNOUNCEMENTS IMPORTANT NOTE REGARDING COVID-19: Following discussions with Ramblers’ Central Office, it has been confirmed that as organized ‘outdoor physical activity events’, Ramblers’ group walks are exempt from other restrictions on social gatherings. This means that group walks in London can continue to go ahead. Each walk is required to meet certain requirements, including maintenance of a register for Test and Trace purposes, and completion of risk assessments. There is no longer a formal upper limit on numbers for walks; however, since Walk Leaders are still expected to enforce social distancing, and given the difficulties of doing this with large numbers, we are continuing to use a compulsory booking system to limit numbers for the time being. Ramblers’ Central Office has published guidance for those wishing to join group walks. Please be sure to read this carefully before going on a walk. It is available on the main Ramblers’ website at www.ramblers.org.uk. The advice may be summarised as: - face masks must be carried and used, for travel to and from a walk on public transport, and in case of an unexpected incident; - appropriate social distancing must be maintained at all times, especially at stiles or gates; - you should consider bringing your own supply of hand sanitiser, and - don’t share food, drink or equipment with others. Some other important points are as follows: 1. BOOKING YOUR PLACE ON A WALK If you would like to join one of the walks listed below, please book a place by following the instructions given below. -

202 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

202 bus time schedule & line map 202 Blackheath, Royal Standard - Crystal Palace View In Website Mode The 202 bus line (Blackheath, Royal Standard - Crystal Palace) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Blackheath, Royal Standard: 12:00 AM - 11:45 PM (2) Crystal Palace: 12:00 AM - 11:45 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 202 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 202 bus arriving. Direction: Blackheath, Royal Standard 202 bus Time Schedule 40 stops Blackheath, Royal Standard Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:00 AM - 11:45 PM Monday 12:00 AM - 11:45 PM Crystal Palace Parade (B), Crystal Palace Bowley Close, London Tuesday 12:00 AM - 11:45 PM Westwood Hill (F) Wednesday 12:00 AM - 11:45 PM Wavel Place, London Thursday 12:00 AM - 11:45 PM Dome Hill Park (G), Upper Sydenham Friday 12:00 AM - 11:45 PM 1 - 7 Woodsyre, London Saturday 12:00 AM - 11:45 PM Wells Park Road (H), Dulwich Crouchmans Close, London Canbury Mews (U), Upper Sydenham Droitwich Close, London 202 bus Info Direction: Blackheath, Royal Standard Sydenham Hill Estate (V) Stops: 40 Trip Duration: 50 min Coombe Road (W), Upper Sydenham Line Summary: Crystal Palace Parade (B), Crystal Bradford Close, London Palace, Westwood Hill (F), Dome Hill Park (G), Upper Sydenham, Wells Park Road (H), Dulwich, Canbury Churchley Road (X) Mews (U), Upper Sydenham, Sydenham Hill Estate (V), Coombe Road (W), Upper Sydenham, Churchley Peak Hill (Z) Road (X), Peak Hill (Z), Sydenham Station / Kirkdale Kirkdale, London (F), Sydenham, Newlands -

358 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

358 bus time schedule & line map 358 Crystal Palace View In Website Mode The 358 bus line (Crystal Palace) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Crystal Palace: 12:00 AM - 11:40 PM (2) Orpington Station: 12:00 AM - 11:40 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 358 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 358 bus arriving. Direction: Crystal Palace 358 bus Time Schedule 76 stops Crystal Palace Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:00 AM - 11:40 PM Monday 12:00 AM - 11:40 PM Orpington Bus Station (E) Station Approach, London Tuesday 12:00 AM - 11:40 PM High Storpington War Memorial (R) Wednesday 12:00 AM - 11:40 PM 299-301 High Street, London Thursday 12:00 AM - 11:40 PM Orpington / Walnuts Centre (X) Friday 12:00 AM - 11:40 PM High Storpington War Memorial (S) Saturday 12:00 AM - 11:40 PM 299-301 High Street, London Hillcrest Road Orpington (M) Sevenoaks Road, London 358 bus Info Sevenoaks Road / Tower Road (D) Direction: Crystal Palace Stops: 76 Sevenoaks Road Orpington Hospital Orpington Trip Duration: 77 min (E) Line Summary: Orpington Bus Station (E), High Helegan Close, London Storpington War Memorial (R), Orpington / Walnuts Centre (X), High Storpington War Memorial (S), Sevenoaks Road Cloonmore Avenue Orpington Hillcrest Road Orpington (M), Sevenoaks Road / (F) Tower Road (D), Sevenoaks Road Orpington Hospital Orpington (E), Sevenoaks Road Cloonmore Avenue Crescent Way (G) Orpington (F), Crescent Way (G), Glentrammon Road Green Street Green (E), Farnborough Hill Bus Garage Glentrammon -

Buses from Battersea Park

Buses from Battersea Park 452 Kensal Rise Ladbroke Grove Ladbroke Grove Notting Hill Gate High Street Kensington St Charles Square 344 Kensington Gore Marble Arch CITY OF Liverpool Street LADBROKE Royal Albert Hall 137 GROVE N137 LONDON Hyde Park Corner Aldwych Monument Knightsbridge for Covent Garden N44 Whitehall Victoria Street Horse Guards Parade Westminster City Hall Trafalgar Square Route fi nder Sloane Street Pont Street for Charing Cross Southwark Bridge Road Southwark Street 44 Victoria Street Day buses including 24-hour services Westminster Cathedral Sloane Square Victoria Elephant & Castle Bus route Towards Bus stops Lower Sloane Street Buckingham Palace Road Sloane Square Eccleston Bridge Tooting Lambeth Road 44 Victoria Coach Station CHELSEA Imperial War Museum Victoria Lower Sloane Street Royal Hospital Road Ebury Bridge Road Albert Embankment Lambeth Bridge 137 Marble Arch Albert Embankment Chelsea Bridge Road Prince Consort House Lister Hospital Streatham Hill 156 Albert Embankment Vauxhall Cross Vauxhall River Thames 156 Vauxhall Wimbledon Queenstown Road Nine Elms Lane VAUXHALL 24 hour Chelsea Bridge Wandsworth Road 344 service Clapham Junction Nine Elms Lane Liverpool Street CA Q Battersea Power Elm Quay Court R UE R Station (Disused) IA G EN Battersea Park Road E Kensal Rise D ST Cringle Street 452 R I OWN V E Battersea Park Road Wandsworth Road E A Sleaford Street XXX ROAD S T Battersea Gas Works Dogs and Cats Home D A Night buses O H F R T PRINCE O U DRIVE H O WALES A S K V Bus route Towards Bus stops E R E IV A L R Battersea P O D C E E A K G Park T A RIV QUEENST E E I D S R RR S R The yellow tinted area includes every Aldwych A E N44 C T TLOCKI bus stop up to about one-and-a-half F WALE BA miles from Battersea Park. -

Catford Town Centre Local Plan Introduction and Background Note: This Does Not Form Part of the Local Plan but Has Been Included for Information Purposes

Lewisham local development framework Catford Town Centre Local Plan INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND Note: This does not form part of the local plan but has been included for information purposes. Catford Town Centre, home of the council’s services and the civic heart of the borough, will be a lively, attractive town centre focused around a high quality network of public spaces. Driven by the redevelopment of key opportunity areas, including the redevelopment of the former Catford Greyhound Stadium site and the Shopping Centre, Catford will have an improved retail offer and will be home to a diverse residential community. The Broadway Theatre and Studio will continue to be a focus for arts and cultural activities and the market will continue to contribute to Catford’s identity. This is the vision for Catford Town Centre; a vision that has This document is the Council’s ‘Proposed Submission been developed over a number of years in conjunction Version’ of the Catford Town Centre Local Plan; it is with may different stakeholders. The Council is committed the version the Council has prepared following public to ensuring regeneration and significant improvement consultation earlier in 2013 on a ‘further options report’ takes place in Catford and there are now a number of key and responds to the comments and suggestions that redevelopment opportunities that provide an exciting were made. It is this version of the Catford Plan that the prospect to change the town centre for the better. Council intends to submit to the Secretary of State who will then appoint an independent Planning Inspector In order to help steer the regeneration of the area, the to determine whether the plan is ‘sound’ and can be Council has updated its planning strategy for the town adopted by the Council. -

AMERICAN PALE Bianca Road APA 4.6% (Bermondsey) a Classic Deep

AMERICAN PALE Bianca Road APA 4.6% (Bermondsey) A classic deep amber APA with fruity and refreshing flavours £4.50 Brixton Atlantic APA 5.4% (Brixton) Burst of tropical fruits for a refreshing American pale finish £4.50 INDIAN PALE ALE Mondo Kemosabe IPA 6.4% (Battersea) Dry, malty IPA, a mingle of flavours on the nose classic £4.50 Pressure Drop Mimic 6.2% (Tottenham) A rye IPA, zesty with a subtle spice £4.50 Hackney Push Eject 6.5 (Hackney) Heavily hopped, unfiltered & unfined. Hazy with tropical notes £4.50 SESSION IPA Mondo Little Victories 4.3% (Battersea) A well balanced session IPA, nice body and a hint of sweetness £4.50 LAGER Portobello Pils 4.6% (White City) Full rounded continental flavoured pilsner £3.95 Mondo All Caps 4.9% (Battersea) Corn like sweetness for this American pils £4.50 Brick Peckham Pils 4.8% (Peckham Rye) Czech style pilsner, light & refreshing £4.50 AMBER Gipsy Hill Southpaw 4.2% (Gipsy Hill) Mouthful of malt and hops meet citrus balance £4.50 SOUR Signature Jam Sour 4% (Leyton) A dry hopped raspberry sour, sharp, sweet, topical and zingy £4.50 Weird Beard Sour Slave 4% (Hanwell) Dry hopped kettle sour with a clean citrus acidity (Vg) £4.50 PALE ALE Hackney Kapow! 4.5% (Hackney) Juicy, tropical dry hopped pal. Unfiltered for bigger flavours £4.50 PORTER Bianca Road Vanilla Coffee Porter 4.5% (Bermondsey) Bitter and sweet combine with a hint of vanilla £4.50 BELGIAN & GRISETTE Structure of Matter 4.5% (Ilford) Smooth and quaffable, orangey hops, spicy and malty taste £4.50 Hello, Grisette me you’re looking for? 4.1% (Hanwell) A taste of fresh fruit salad with £4.50 a wheat serenade STOUT £4.50 Brixton Windrush Stout 5% (Brixton) Rich, chocolatey & smooth, with a creamy finish £5.00 Lord Malmölé 7.2% (Battersea) Mondo and Malmo brewery combine for this wonderful stout £4.25 Belleville Southie Stout 5.1% (Wandsworth) Rich and silky with a citrusy-herbal kick. -

THOMSON REUTERS MAP.Ai

PUBLIC TRANSPORT PUBLIC TRANSPORT Watford M Hatfield A1 2 LIMEHOUSE DOCKLAND 1 M25 1 DLR 1 N TRAIN STATION LIGHT RAILWAY M Hendon A1 27 Situated on Commercial Road Canary Wharf Station. Situated High A406 (A13), walk to the Limehouse at the centre of North and South Wycombe Basildon The Thomson Reuters Building M 2 DLR Station and catch a Colonnade. The Station is a two M4 5 South Colonnade 0 A40 A1 3 connecting train to Canary minute walk from our building. A1 3 Slough Canary Wharf Wharf. CITY OF • London C ity LONDON Airport London M4 Tilbury LONDON CITY LONDON UNDERGROUND • A20 5 2 E14 5ep CANARY WHARF • AIRPORT Heathrow A205 M Airport Jubilee Line Extention – links Catch a connecting London Gravesend A3 Croydon Canary Wharf with Waterloo City Airport shuttle bus to SECTION M 2 +44 (0)20 7250 1122 0 Station and London Bridge, Canary Wharf DETAILED M3 BELOW M25 thomsonreuters.com also other tube lines. Wok ing Limehouse MANOR Train Station A Docklands B BURDETT 1 ROAD 1 0 A1 206 2 ROAD Blackwell Tunnel 2 Isle of Dogs 1 Dover A1 02 N C anary Wharf WESTFERRY C IRC US (A1 3) Folkestone COMMERCIAL Royal Docks ROAD C ity 3 C anary A1 Wharf Airport C . London A1 3 One Way COMMERCIAL EAST INDIA ROAD C abot Square DOCK ROAD A1 3 L I M E H O U S E P P C anary Wharf Start here DLR A1 3 A1 3 From the East To Tower Gateway A L L (A1 3) & Central London 6 S A I N T S 0 2 1 P O P L A R Start here W E S T F E R R Y A C . -

Upper Tideway (PDF)

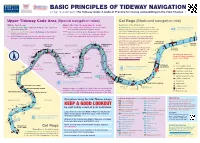

BASIC PRINCIPLES OF TIDEWAY NAVIGATION A chart to accompany The Tideway Code: A Code of Practice for rowing and paddling on the Tidal Thames > Upper Tideway Code Area (Special navigation rules) Col Regs (Starboard navigation rule) With the tidal stream: Against either tidal stream (working the slacks): Regardless of the tidal stream: PEED S Z H O G N ABOVE WANDSWORTH BRIDGE Outbound or Inbound stay as close to the I Outbound on the EBB – stay in the Fairway on the Starboard Use the Inshore Zone staying as close to the bank E H H High Speed for CoC vessels only E I G N Starboard (right-hand/bow side) bank as is safe and H (right-hand/bow) side as is safe and inside any navigation buoys O All other vessels 12 knot limit HS Z S P D E Inbound on the FLOOD – stay in the Fairway on the Starboard Only cross the river at the designated Crossing Zones out of the Fairway where possible. Go inside/under E piers where water levels allow and it is safe to do so (right-hand/bow) side Or at a Local Crossing if you are returning to a boat In the Fairway, do not stop in a Crossing Zone. Only boats house on the opposite bank to the Inshore Zone All small boats must inform London VTS if they waiting to cross the Fairway should stop near a crossing Chelsea are afloat below Wandsworth Bridge after dark reach CADOGAN (Hammersmith All small boats are advised to inform London PIER Crossings) BATTERSEA DOVE W AY F A I R LTU PIER VTS before navigating below Wandsworth SON ROAD BRIDGE CHELSEA FSC HAMMERSMITH KEW ‘STONE’ AKN Bridge during daylight hours BATTERSEA