Philip II Versus William Cecil: the Cleaving of Christendom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Instruction Av 04/2020 Issued by the Management Of

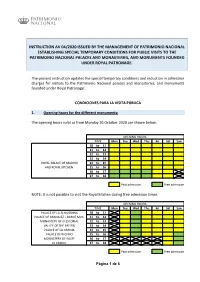

INSTRUCTION AV 04/2020 ISSUED BY THE MANAGEMENT OF PATRIMONIO NACIONAL ESTABLISHING SPECIAL TEMPORARY CONDITIONS FOR PUBLIC VISITS TO THE PATRIMONIO NACIONAL PALACES AND MONASTERIES, AND MONUMENTS FOUNDED UNDER ROYAL PATRONAGE. The present instruction updates the special temporary conditions and reduction in admission charges for visitors to the Patrimonio Nacional palaces and monasteries, and monuments founded under Royal Patronage: CONDICIONES PARA LA VISITA PÚBLICA 1. Opening hours for the different monuments: The opening hours valid as from Monday 26 October 2020 are shown below: OPENING HOURS TIME Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 10 to 11 11 to 12 12 to 13 13 to 14 ROYAL PALACE OF MADRID 14 to 15 AND ROYAL KITCHEN 15 to 16 16 to 17 17 to 18 Paid admission Free admission NOTE: It is not possible to visit the Royal Kitchen during free admission times. OPENING HOURS TIME Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun PALACE OF LA ALMUDAINA 10 to 11 PALACE OF ARANJUEZ + BARGE MUS. 11 to 12 MONASTERY OF El ESCORIAL 12 to 13 VALLEY OF THE FALLEN 13 to 14 PALACE OF LA GRANJA 14 to 15 PALACE OF RIOFRIO 15 to 16 MONASTERY OF YUSTE 16 to 17 EL PARDO 17 to 18 Paid admission Free admission Página 1 de 6 OPENING HOURS TIME Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 10:00 to 10:30 10:30 to 11 11 to 12 12 to 13 CONVENT OF SANTA MARIA LA REAL HUELGAS 13 to 14 14 to 15 CONVENT OF SANTA CLARA TORDESILLAS 15 to 16 16 to 17 17 to 18 18 to 18:30 Paid admission Free admission The Casas del Príncipe (at El Pardo and El Escorial), Casa del Infante (at El Escorial) and Casa del Labrador (at Aranjuez) will not be open. -

WW2-Spain-Tripbook.Pdf

SPAIN 1 Page Spanish Civil War (clockwise from top-left) • Members of the XI International Brigade at the Battle of Belchite • Bf 109 with Nationalist markings • Bombing of an airfield in Spanish West Africa • Republican soldiers at the Siege of the Alcázar • Nationalist soldiers operating an anti-aircraft gun • HMS Royal Oakin an incursion around Gibraltar Date 17 July 1936 – 1 April 1939 (2 years, 8 months, 2 weeks and 1 day) Location Spain Result Nationalist victory • End of the Second Spanish Republic • Establishment of the Spanish State under the rule of Francisco Franco Belligerents 2 Page Republicans Nationalists • Ejército Popular • FET y de las JONS[b] • Popular Front • FE de las JONS[c] • CNT-FAI • Requetés[c] • UGT • CEDA[c] • Generalitat de Catalunya • Renovación Española[c] • Euzko Gudarostea[a] • Army of Africa • International Brigades • Italy • Supported by: • Germany • Soviet Union • Supported by: • Mexico • Portugal • France (1936) • Vatican City (Diplomatic) • Foreign volunteers • Foreign volunteers Commanders and leaders Republican leaders Nationalist leaders • Manuel Azaña • José Sanjurjo † • Julián Besteiro • Emilio Mola † • Francisco Largo Caballero • Francisco Franco • Juan Negrín • Gonzalo Queipo de Llano • Indalecio Prieto • Juan Yagüe • Vicente Rojo Lluch • Miguel Cabanellas † • José Miaja • Fidel Dávila Arrondo • Juan Modesto • Manuel Goded Llopis † • Juan Hernández Saravia • Manuel Hedilla • Carlos Romero Giménez • Manuel Fal Conde • Buenaventura Durruti † • Lluís Companys • José Antonio Aguirre Strength 1936 -

Charles Clifford, Fotografías 1853 - 1863 Subasta 19 I 10 I 2016 JUANNARANJO

Charles Clifford, fotografías 1853 - 1863 Subasta 19 I 10 I 2016 JUANNARANJO SUBASTA AUCTION 19I 10 I 2016 19 : 00 h Charles Clifford Fotografías photographs 1853-1963 Experimentaciones y fotografías no comercializadas Experiments & uncommercialized photographs Organizada por Juan Naranjo s.l. Casanova 136-138 B-3 08036 Barcelona (España) Tel. (34) 93 452 81 64 y (34) 659 95 66 48 email: [email protected] www.juannaranjo.eu Visionado de las fotografías Viewing photographs París 5 octubre 10 h a 14 h y 16 h a 19 h 6 octubre 10 h a 14 h y 16 h a 19 h 1 Square d' Orle ans,80 rueTaitbout, 75009 Paris, tel. (+33)1 401 68 080 Barcelona Madrid 13 octubre 10 h a 14 h y 16 h a 19 h 17 octubre 17 h a 20 h 14 octubre 10 h a 14 h y 16 h a 19 h 18 octubre 10 h a 14 h y 16 h a 20 h Casanova 136-138 B-3ª 08036 Barcelona 19 octubre 10 h a 15 h Tel. (34) 93 452 81 64 Paseo de la Castellana 70 bajos (entrada por el patio de manzana) 28046 Madrid Tel. (34) 659 95 66 48 Subasta Auction 19 I 10 I 2016 19 : 00 h Juan Naranjo (Madrid) Paseo de la Castellana 70 bajos (entrada por el patio de manzana) 28046 Madrid Tel. (34) 659 95 66 48 NARANJO Charles Clifford fue uno de los fotógrafos más importantes de los Charles Clifford que trabajaron en España en el siglo XIX y el más reconocido a nivel internacional. -

Cooperation Network of European Routes of Emperor Charles V

COOPERATION NETWORK OF EUROPEAN ROUTES OF EMPEROR CHARLES V 1 COOPERATION NETWORK OF EUROPEAN ROUTES OF EMPEROR CHARLES V INDEX 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 3 2. MEMBERS OF THE COOPERATION NETWORK .................................................... 4 3. CULTURAL EUROPEAN ITINERARY OF THE EUROPEAN ROUTES OF CHARLES V .................................................................... 8 4. PROJECTS ............................................................................................................ 11 5. MARKETING OF THE EUROPEAN ROUTES OF CHARLES V .................................. 32 6. SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE OF THE COOPERATION NETWORK .............................. 40 7. 2017 ACTIVITIES ................................................................................................. 44 8. 500th ANNIVERSARY OF THE FIRST ARRIVAL OF PRINCE CHARLES V IN SPAIN ......................................................................... 72 2 COOPERATION NETWORK OF EUROPEAN ROUTES OF EMPEROR CHARLES V 1. INTRODUCTION On 25thApril 2007, the Cooperation Network of the European Routes of Emperor Charles V was created in Medina de Pomar (Burgos) with the objective of protecting and promoting the tourist, historical-cultural and economic resources of the European Routes of Charles V. Currently it comprises more than 60 cities and historical sites along the length and breadth of the journeys covered by Charles Hapsburg between 1517 and 1557. Since 2007 the -

User Guide to Book and Buy Tickets

USER GUIDE TO BOOK AND BUY TICKETS Edition 2.5 USER GUIDE TO BOOK AND BUY TICKETS https://entradas.patrimonionacional.es/ Sales and reservations: 902 044 454. Support service: 902 044 414/[email protected] INDEX 1. GENERAL PROCEDURES .......................................................................................................................... 3 1.1.- WHY SHOULD I REGISTER? ...................................................................................................................... 3 1.2.- HOW CAN I REGISTER? ............................................................................................................................. 3 1.3.- HOW TO LOGIN AND LOGOUT? ................................................................................................................. 4 1.4.- HOW CAN I CHANGE MY USER DETAILS? .................................................................................................. 4 1.5.- WHEN CAN I MAKE MY RESERVATIONS? .................................................................................................. 5 1.6.- GETTING AN INVOICE OF MY PURCHASE? ................................................................................................. 5 1.7.- WHAT PRICES? ......................................................................................................................................... 6 2. PURCHASE OF INDIVIDUAL TICKETS ................................................................................................. 9 2.1.- PURCHASE INDIVIDUAL -

Collector Coins Issued in Euro*

Departamento de Emisión y Caja COLLECTOR COINS ISSUED IN EURO* SPANISH STATE GAZETTE FACE MOTIF MINTAGE LIMIT ISSUE METAL MINISTRY OF ECON. ORDER VALUE (€)* FRONT REVERSE No. OF COINS GOLD COLLECTOR COINS 932/2002, April 17 International Gaudí Year 2002 Gold 400 Antonio Gaudí Casa Batlló 3.000 935/2002, April 17 World Football Cup 2002 Gold 200 Footballers Net and boot 4.000 319/2003, February 10 First anniversary of the euro Gold 200 King and Queen of Spain Europa being abducted by Zeus 20.000 2651/2003, September 24 25th Anniversary of the Spanish Constitution Gold 200 King and Queen of Spain Frontispiece of the Palace of Congress 4.000 3417/2003, November 26 FIFA World Cup Germany 2006 - Issue 2003 Gold 100 King Juan Carlos I Goalkeeper 25.000 3418/2003, November 26 Centenary of the birth of Salvador Dalí Gold 400 Salvador Dalí “Figure at a window” 5.000 41/2004, January 8 The Europa Program - Enlargement of the European Union Gold 200 King Juan Carlos I New European Union member states 5.000 636/2004, March 4 Wedding of the Prince of Asturias Gold 200 King and Queen of Spain Prince and Princess of Asturias 30.000 3232/2004, September 30 FIFA World Cup Germany 2006 – Issue 2004 Gold 100 King Juan Carlos I Football goal line 25.000 3233/2004, September 30 5th Centenary of Isabella I of Castile Gold 200 Catholic King and Queen Granada's Coat of Arms 5.000 257/2005, February 3 4th Centenary of the publication of Don Quixote Gold 400 D.Quijote reading D.Quijote and Sancho mounting 3.000 628/2005, March 8 The Europa Program - Peace and Freedom Gold 200 King Juan Carlos I Hands shaking over the EU map 4.000 3167/2005, October 6 25th Anniversary of the Prince Asturias Awards Gold 200 H. -

Broken Boundaries: Developing Portrayals of Iberian Islam in Castilian Texts of the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries

Broken Boundaries: Developing Portrayals of Iberian Islam in Castilian Texts of the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries BY Robert Iafolla A Study Presented to the Faculty of Wheaton College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation with Departmental Honors in History Norton, Massachusetts May 13, 2013 1 Table of Contents Note on Translation 2 Introduction 3 1. Bounded Interaction: Christians and Muslims in Literature from 28 the Fifteenth Century Frontier 2. Continuity and Change: The Sixteenth Century and Frontiers in 70 Time 3. Moriscos in Revolt: New Portrayals on the Old Frontier 114 Conclusion 159 Bibliography 162 2 Note on Translation Unless otherwise indicated, all translations from sources are mine. In the footnotes, I have kept the spelling of most words as it was in the source, but in a few instances I have changed it for the sake of clarity if the meaning would not be immediately apparent. Within the text, names of people or places that have a common spelling in English have been rendered according to that spelling, so for example Castilla is written as Castile and Felipe as Philip. Also, I have kept the spelling of individual names as they appear in the sources, except where there is a clear preference for an alternative spelling in the majority of modern sources. For instance, Diego Hurtado de Mendoza's spelling Abén Humeya, for the first leader of the Morisco revolt, is changed to Abén Humaya. 3 Introduction The year 1492 looms large in the history of the Iberian Peninsula. In January the city of Granada, the last remaining outpost of Islamic political power in Iberia after eight centuries, surrendered to the armies of the Catholic Monarchs Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile. -

El Arte Del Poder Armaduras Y Retratos De La España Imperial

The Art of Power Royal Armor and Portraits from Imperial Spain El arte del poder Armaduras y retratos de la España imperial álvaro soler del campo The exhibition has been organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, the State Corporation for Spanish Cultural Action Abroad (SEACEX), and the Patrimonio Nacional of Spain. La exposición está organizada por la National Gallery of Art de Washington, la Sociedad Estatal para la Acción Cultural Exterior de España (SEACEX) y Patrimonio Nacional. The exhibition has been organized in association with the Spanish Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation and the Ministry of Culture, with the assistance of the Embassy of Spain in Washington, DC. The exhibition is supported by an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities. La exposición cuenta con la colaboración de los ministerios de Asuntos Exteriores y de Cooperación y de Cultura de España, y el apoyo de la Embajada de España en Washington, DC. La exposición está apoyada por la garantía del Consejo Federal de las Artes y Humanidades de los Estados Unidos. EMBASSY OF SPAIN WASHINGTON The exhibition The Art of Power: Royal Armor and Portraits from Imperial Spain presents a splendid selection of armor and portraits of the Spanish monarchy, specifically from the period spanning the European discovery of America to the emergence of the United States as an independent, sovereign nation. The Armory of the Royal Palace in Madrid has been, and remains today, the custodian of arms and armor that bear rich and complex decoration conveying an image of power, and that also provided models for official portraits as well as those commemorating notable political or military events. -

Tc Spain 2011

THE BEST OF EUROPE 2014 34 Signature Holidays byT ourcrafters France Spain Germany Austria Switzerland Hungary Czech RepubEsliccorted Hosted Greece Independent Turkey Fly & Drive Historical Villas Cruises Extensions Food & Wine Tours www.tourcrafters.com Edinburgh THE BEST OF Hamburg Dublin Amsterdam Berlin EUROPE London Germany Bruges Cologne 2014 Brussels Praga Normandy Frankfurt Paris Mont Saint Michel Munich Vienna Loire Budapest Zurich Switzerland France Italy Venice Bordeaux Genova Portofino Ravenna Montecarlo/Monaco Portovenere Bilbao Nice/Villefranche La Coruña Livorno Marseille Elba Ajaccio Roma Barcelona Segovia Instanbul Madrid Naples Capri Greece Toledo Salerno Valencia Turkey Spain Palma de Mallorca Cagliari Corfu Lipari Kusadasi Messina Cefalu Athens Cordoba Taormina Bodrum Sevilla Granada Katakolon Mykonos Mamaris Agrigento Syracuse Gibraltar Malaga Santorini Rhodes Crete Index Introduction to our Specials 2-3 Spain Hotels 4-9 Spain by Train 10-11 Spain by Car 12-13 Spain Escorted tour 14-15 London Hotels & Tours 16-17 France Chateaux & Hotel de Charme 18-19 France Hotels & Honeymoon Package 20-21 France by Train 22-25 France Escorted tours 26-29 Austria Hotels & tours 30-33 >> See our web brochure Prague & Budapest Hotels & tours 34-35 for more package ideas. Austria /Imperial Capitals tour 36-37 Germany /Switzerland Hotels 38-39 Germany /Switzerland Escorted tours 40-47 Greece Athens Hotels & tours 48-49 Greece Packages 50-51 Greece Island Hotels 52-53 Greece Cruise Packages 54-57 Crete, Rhodes & Paros 58-59 Greece Honeymoon Packages 60-61 Istanbul Hotels & tours 62 Turkey Escorted Packages 63 TourCrafters Exclusive Escorted Tours TourCrafters invites you to experience our exclusive Escorted tours! Tours crafted to enhance your experience in Europe, with its wealth of art, culture, wine, delicious food, and breathtaking landscapes. -

El-Cat-Hispanic-Multimedia

LEA Book Distributors (Libros de España y América) 170-23 83rd Avenue, Jamaica Hills, New York 11432 Tel: 1(718) 291-9891 • Fax: 1(718) 291-9830 E-Mail: [email protected] • Website: www.leabooks.com Federal I.D. No. & N.Y. State Resale Tax No.: 06-1124429 3-Jan-07 FILMS FOR THE HUMANITIES: SPAIN & LATIN AMERICA SPANISH CULTURE ISBN TitleName ListPrice Language Brand RunTimeCopyrightDateEXTItemID FormatNameFullDescription Spanish History & Culture 978-1-4213-2702-0 A la Sombra de la Revolucion-in $149.95 Spanish Films 45 1/1/2004 33968-KS DVD Charles IV succeeded to the Spanish throne in 1788. One year later, the cataclysmic revolution in Spanish neighboring France dealt European monarchism a blow of seismic proportions. Focusing on Charles' reign-conducted with extreme passivity and ending in abdication-this program uses film clips, dramatizations, paintings, and architectural landmarks to examine a country caught in the throes of sociopolitical turmoil. Queen Maria Luisa and her lover Manuel de Godoy, the true royal powers, are spotlighted as Spain's fortunes in the shadow of Napoleonic France are appraised. Not available in French-speaking Canada. An RTVE Production. (Spanish, 45 minutes) 978-1-4213-2722-8 A la Sombra de la Revolucion-in $149.95 Spanish/EnglishFilms Subtitles 45 1/1/2004 34880-KS DVD Charles IV succeeded to the Spanish throne in 1788. One year later, the cataclysmic revolution in Spanish with English Subtitles neighboring France dealt European monarchism a blow of seismic proportions. Focusing on Charles' reign-conducted with extreme passivity and ending in abdication-this program uses film clips, dramatizations, paintings, and architectural landmarks to examine a country caught in the throes of sociopolitical turmoil. -

Impact of European Cultural Routes on Smes' Innovation And

Impact of European Cultural Routes on SMEs’ innovation and competitiveness The study is financed under the Competitiveness and Innovation Framework Programme (CIP) which aims to encourage the competitiveness of European enterprises 1 Contents Executive summary Part I Analysing the impact of the European Cultural Routes 1. Introduction 1.1 Study goals and concepts definitions 1.2 Methodological approach 2. Cultural Routes of the Council of Europe 2.1 History of the programme 2.2 Cultural Routes programme today 3. Cultural tourism trends in Europe: a context for the development of Cultural Routes 3.1 Cultural tourism: major drivers and niches 3.2 Challenges and created opportunities for Cultural Routes Conclusions 4. Governance of the Cultural Routes networks 4.1 Network structure and resources 4.2 Fiscal management and funding opportunities Conclusions 5. SMEs’ innovation and clustering within the Cultural Routes networks 5.1 Cultural Routes’ impact on SMEs’ innovation 5.2 Clustering between Cultural Route partners and local SMEs 5.3 Measuring the Cultural Routes’ impact and SMEs’ performance Conclusions 6. Increasing attractiveness of the lesser known European destinations via the Council of Europe Cultural Routes programme 6.1 Developing the Council of Europe Cultural Routes brand 6.2 Cultural Routes programme branding and marketing 6.3 Establishing sustainability standards 7. Conclusions and recommendations 7.1 Conclusions 2 7.2 Recommendations Part II Cultural Route case studies The Hansa Cultural Route Routes of the Legacy of al-Andalus The Routes of the Olive Tree Via Francigena Transromanica Review of the relevant European and international projects Bibliography Appendices 3 Executive summary The study on the impact of European Cultural Routes on SMEs’ innovation and competitiveness was jointly launched by the European Commission (EC) and the Council of Europe (Council) in September 2010. -

Caballeros De Yuste N.º 34 • 3º Y 4º Trimestre • Año 2017 Caballeros De Yuste Revista Cultural De La Real Asociación Y Fundación “Caballeros De Yuste”

Fundación Caballeros de Yuste N.º 34 • 3º y 4º trimestre • Año 2017 Caballeros de Yuste Revista Cultural de la Real Asociación y Fundación “Caballeros de Yuste” . Sumario Pag. 3 .................................................................................................................La globalización y los valores éticos 9 .........................................................................................................................Globalization and ethical values 15 ................................................................................................ Die Gobalisierung und die ethischen Werte 21 ...................................................... Necrológica. Maestro: Excmo. Sr. D. José María Castán Vázquez 23 ...............................................................................................................Las lecturas del Emperador en Yuste 28 ......................................................................................................... Carlos el joven duque de Luxemburgo 32 ........................................................................................................ Carlos the young duke of Luxembourg 37 .........................................................................................................Karl, der junge Herzog von Luxemburg 41 ............................................................................................................................................... Carlos V en Palencia 44 ..................................................................