The Limits of Community in the Twentieth-Century Novel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Angel of Ferrara

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Goldsmiths Research Online The Angel of Ferrara Benjamin Woolley Goldsmith’s College, University of London Submitted for the degree of PhD I declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own Benjamin Woolley Date: 1st October, 2014 Abstract This thesis comprises two parts: an extract of The Angel of Ferrara, a historical novel, and a critical component entitled What is history doing in Fiction? The novel is set in Ferrara in February, 1579, an Italian city at the height of its powers but deep in debt. Amid the aristocratic pomp and popular festivities surrounding the duke’s wedding to his third wife, the secret child of the city’s most celebrated singer goes missing. A street-smart debt collector and lovelorn bureaucrat are drawn into her increasingly desperate attempts to find her son, their efforts uncovering the brutal instruments of ostentation and domination that gave rise to what we now know as the Renaissance. In the critical component, I draw on the experience of writing The Angel of Ferrara and nonfiction works to explore the relationship between history and fiction. Beginning with a survey of the development of historical fiction since the inception of the genre’s modern form with the Walter Scott’s Waverley, I analyse the various paratextual interventions—prefaces, authors’ notes, acknowledgements—authors have used to explore and explain the use of factual research in their works. I draw on this to reflect in more detail at how research shaped the writing of the Angel of Ferrara and other recent historical novels, in particular Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall. -

The Angel of Ferrara

The Angel of Ferrara Benjamin Woolley Goldsmith’s College, University of London Submitted for the degree of PhD I declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own Benjamin Woolley Date: 1st October, 2014 Abstract This thesis comprises two parts: an extract of The Angel of Ferrara, a historical novel, and a critical component entitled What is history doing in Fiction? The novel is set in Ferrara in February, 1579, an Italian city at the height of its powers but deep in debt. Amid the aristocratic pomp and popular festivities surrounding the duke’s wedding to his third wife, the secret child of the city’s most celebrated singer goes missing. A street-smart debt collector and lovelorn bureaucrat are drawn into her increasingly desperate attempts to find her son, their efforts uncovering the brutal instruments of ostentation and domination that gave rise to what we now know as the Renaissance. In the critical component, I draw on the experience of writing The Angel of Ferrara and nonfiction works to explore the relationship between history and fiction. Beginning with a survey of the development of historical fiction since the inception of the genre’s modern form with the Walter Scott’s Waverley, I analyse the various paratextual interventions—prefaces, authors’ notes, acknowledgements—authors have used to explore and explain the use of factual research in their works. I draw on this to reflect in more detail at how research shaped the writing of the Angel of Ferrara and other recent historical novels, in particular Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall. -

Entertainment Plus Karaoke by Title

Entertainment Plus Karaoke by Title #1 Crush 19 Somethin Garbage Wills, Mark (Can't Live Without Your) Love And 1901 Affection Phoenix Nelson 1969 (I Called Her) Tennessee Stegall, Keith Dugger, Tim 1979 (I Called Her) Tennessee Wvocal Smashing Pumpkins Dugger, Tim 1982 (I Just) Died In Your Arms Travis, Randy Cutting Crew 1985 (Kissed You) Good Night Bowling For Soup Gloriana 1994 0n The Way Down Aldean, Jason Cabrera, Ryan 1999 1 2 3 Prince Berry, Len Wilkinsons, The Estefan, Gloria 19th Nervous Breakdown 1 Thing Rolling Stones Amerie 2 Become 1 1,000 Faces Jewel Montana, Randy Spice Girls, The 1,000 Years, A (Title Screen 2 Becomes 1 Wrong) Spice Girls, The Perri, Christina 2 Faced 10 Days Late Louise Third Eye Blind 20 Little Angels 100 Chance Of Rain Griggs, Andy Morris, Gary 21 Questions 100 Pure Love 50 Cent and Nat Waters, Crystal Duets 50 Cent 100 Years 21st Century (Digital Boy) Five For Fighting Bad Religion 100 Years From Now 21st Century Girls Lewis, Huey & News, The 21st Century Girls 100% Chance Of Rain 22 Morris, Gary Swift, Taylor 100% Cowboy 24 Meadows, Jason Jem 100% Pure Love 24 7 Waters, Crystal Artful Dodger 10Th Ave Freeze Out Edmonds, Kevon Springsteen, Bruce 24 Hours From Tulsa 12:51 Pitney, Gene Strokes, The 24 Hours From You 1-2-3 Next Of Kin Berry, Len 24 K Magic Fm 1-2-3 Redlight Mars, Bruno 1910 Fruitgum Co. 2468 Motorway 1234 Robinson, Tom Estefan, Gloria 24-7 Feist Edmonds, Kevon 15 Minutes 25 Miles Atkins, Rodney Starr, Edwin 16th Avenue 25 Or 6 To 4 Dalton, Lacy J. -

Product Corning to Market (Ed)

Healthy Sign: More Product Corning To Market (Ed) ... Davis To Col/Epic Confab: Challenge Of 'Aggre- ssive Competition' ... Tyrell Label Thr Col ... Music Now Key In- August 8. 1970 gredient Of Allied Artistss s Film, TV Units ... Bell: Top 6 Mos. In Histo casábar ... Japan Surge On Soundtrack Product; King INTERNATIONAL MUSIC SECTION 'Definitive' 7 -LP Set ... Eurovision Changes 'TOMMY,' THAT'S WHO INT'L SECTION BEGINS ON PAGE 4 Pickettywitch The Manhattan Borough -Wide Chorus for The Friends of Music of New York City and their friends have a new hit single called "Hi -De -Ho:' (Their friends.) BLOOD,SWEAT& TEARS 3 Symphony For The Devil-Sympathy For The Devil Somethin' Comin' On/The Battle 40,000 Headmen/Hi-De-Ho/Lucretia MacEvil Blood, Sweat & Tears recorded "Hi -De -Ho" with 27 Junior High School students chosen from The Manhattan Borough -Wide Chorus for The Friends of Music (most of whom live in Ghetto neighborhoods). It isn't often that a single gets such tremendous air play and sales in only two weeks. It isn't often that you can look at the face of a kid and know that a recording session accomplished more than the making of a hit record. *Also available on tape. ON COLUMBIA RECORDS* iiiuAW iu iiAa HUMi=ii=iiäï /MIMI IIMU\MUM THE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC-RECORD WEEKLY VOL. XXXII - Number 1/August 8 1970 Publication Office / 1780 Broadway, New York, New York 10019 / Telephone: JUdson 6-2640 /Cable Address: Cash Box, N.Y. GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher MARTY OSTROW Vice President IRV LICHTMAN Editor in Chief EDITORIAL MARV GOODMAN Assoc. -

Fearless Daughters of the Bible

Fearless Daughters of the Bible What You Can Learn from 22 Women Who Challenged Tradition, Fought Injustice and Dared to Lead J. Lee Grady F J. Lee Grady, Fearless Daughters of the Bible Chosen Books, a division of Baker Publishing Group, © 2012. Used by permission. _Grady_FearlessDaughters_NS_djm.indd 3 8/20/12 1:12 PM These websites are hyperlinked. www.bakerpublishinggroup.com www.bakeracademic.com www.brazospress.com www.chosenbooks.com www.revellbooks.com www.bethanyhouse.com © 2012 by J. Lee Grady Published by Chosen Books 11400 Hampshire Avenue South Bloomington, Minnesota 55438 www.chosenbooks.com Chosen Books is a division of Baker Publishing Group, Grand Rapids, Michigan Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means—for example, electronic, photocopy, recording—without the prior written permission of the publisher. The only exception is brief quotations in printed reviews. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this title. ISBN 978-0-8007-9531-3 (pbk.) Unless otherwise indicated, Scripture quotations are from the New American Standard Bible®, copyright © 1960, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995 by The Lockman Foundation. Used by permission. Scripture quotations identified The Message are from The Message by Eugene H. Peter- son, copyright © 1993, 1994, 1995, 2000, 2001, 2002. Used by permission of NavPress Publishing Group. All rights reserved. Scripture quotations identified KJV are from the King James Version of the Bible. Cover design by Dan Pitts 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 J. -

NATHAN ZUCKERMAN, the UNIVERSITY of CHICAGO, and PHILIP ROTH's NEO-ARISTOTELIAN POETICS by DANIEL PAUL A

PLATO’S COMPLAINT: NATHAN ZUCKERMAN, THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO, AND PHILIP ROTH’S NEO-ARISTOTELIAN POETICS by DANIEL PAUL ANDERSON Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Thesis Adviser: Dr. Judith Oster Department of English CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY January, 2008 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis of ______________________________________________________ candidate for the Master of Arts degree *. (signed)_______________________________________________ (chair of the committee) ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ (date) _______________________ *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. 1 Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………...…………………………....2 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………….3 Chapter One: The Ghost Writer………………………………………………………….20 Chapter Two: Zuckerman Unbound……………………………………………………...40 Chapter Three: The Anatomy Lesson…………………………………………………….54 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………….78 Works Cited……………………………………………………………………………...89 2 Plato’s Complaint: Nathan Zuckerman, the University of Chicago, and Philip Roth’s Neo-Aristotelian Poetics Abstract by DANIEL PAUL ANDERSON This thesis examines how Philip Roth’s education at the University of Chicago shaped -

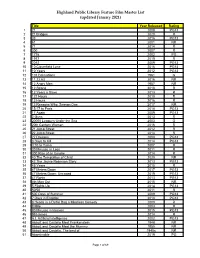

Highland Public Library Feature Film Master List (Updated January 2021)

Highland Public Library Feature Film Master List (updated January 2021) Title Year Released Rating 1 21 2008 PG13 2 21 Bridges 2020 R 3 33 2016 PG13 4 61 2001 NR 5 71 2014 R 6 300 2007 R 7 1776 2002 PG 8 1917 2019 R 9 2012 2009 PG13 10 10 Cloverfield Lane 2016 PG13 11 10 Years 2012 PG13 12 101 Dalmatians 1961 G 13 11.22.63 2016 NR 14 12 Angry Men 1957 NR 15 12 Strong 2018 R 16 12 Years a Slave 2013 R 17 127 Hours 2010 R 18 13 Hours 2016 R 19 13 Reasons Why: Season One 2017 NR 20 15:17 to Paris 2018 PG13 21 17 Again 2009 PG13 22 2 Guns 2013 R 23 20000 Leagues Under the Sea 2003 G 24 20th Century Women 2016 R 25 21 Jump Street 2012 R 26 22 Jump Street 2014 R 27 27 Dresses 2008 PG13 28 3 Days to Kill 2014 PG13 29 3:10 to Yuma 2007 R 30 30 Minutes or Less 2011 R 31 300 Rise of an Empire 2014 R 32 40 The Temptation of Christ 2020 NR 33 42 The Jackie Robinson Story 2013 PG13 34 45 Years 2015 R 35 47 Meters Down 2017 PG13 36 47 Meters Down: Uncaged 2019 PG13 37 47 Ronin 2013 PG13 38 4th Man Out 2015 NR 39 5 Flights Up 2014 PG13 40 50/50 2011 R 41 500 Days of Summer 2009 PG13 42 7 Days in Entebbe 2018 PG13 43 8 Heads in a Duffel Bag a Mindless Comedy 2000 R 44 8 Mile 2003 R 45 90 Minutes in Heaven 2015 PG13 46 99 Homes 2014 R 47 A.I. -

The Image of Walking in Hawthorne's Fiction (Journey Motif, Pilgrimage)

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1986 The mI age of Walking in Hawthorne's Fiction (Journey Motif, Pilgrimage). Frances Murphy Zauhar Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Zauhar, Frances Murphy, "The mI age of Walking in Hawthorne's Fiction (Journey Motif, Pilgrimage)." (1986). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 4216. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/4216 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a manuscript sent to us for publication and microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to pho tograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. Pages in any manuscript may have indistinct print. In all cases the best available copy has been filmed. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. Manuscripts may not always be complete. When it is not possible to obtain missing pages, a note appears to indicate this. 2. When copyrighted materials are removed from the manuscript, a note ap pears to indicate this. 3. Oversize materials (maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sec tioning the original, beginning at the upper left hand comer and continu ing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

ABSTRACT “Books Are Made out of Books”: a Study of Influence From

ABSTRACT “Books Are Made Out of Books”: A Study of Influence from the Cormac McCarthy Archives Michael L. Crews, Ph.D Director: James E. Barcus, Ph.D. In December of 2007, the Southwestern Writers Collection, part of the Wittliff Collection of the Alkek Library at Texas State University, in San Marcos, Texas, acquired Cormac McCarthy’s literary papers. The collection contains early drafts, correspondence, and notes. Access to the archives makes possible scholarly investigations into influences on McCarthy’s work, a subject that, given the author’s reticence about discussing other writers, has been largely relegated to informed speculation. The following study moves scholarly interest in McCarthy’s influences away from speculation and toward a more solid foundation based on detailed manuscript research. By chronicling McCarthy’s references to writers, books, and thinkers in his correspondence, in working notes, and in marginalia found in early drafts, I have provided a reference guide that will serve other scholars engaged in the study of Cormac McCarthy’s influences. The work is composed primarily of alphabetized entries corresponding to the names of writers, artists, and thinkers found in the archives. For instance, the first entry is Edward Abbey, the last the ancient Greek philosopher Xenophanes. Each entry describes the location of the reference in the archives by identifying the box and folder in which it is contained, and describes the context of its appearance. For instance, the reference to Edward Abbey appears in Box 19, Folder 14, which contains McCarthy’s notes for Suttree. It refers to a specific passage in Abbey’s book Desert Solitaire. -

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev

BEN-GURION UNIVERSITY OF THE NEGEV THE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF FOREIGN LITERATURES AND LINGUISTICS FEMINIST DISCOURSE AND THE CHANGING FIGURE OF THE VAMPIRE, 1890s-2000s THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS VALERIE KHASKIN UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF: PROF. EITAN BAR-YOSEF November 2014 BEN-GURION UNIVERSITY OF THE NEGEV THE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF FOREIGN LITERATURES AND LINGUISTICS FEMINIST DISCOURSE AND THE CHANGING FIGURE OF THE VAMPIRE, 1890s-2000s THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS VALERIE KHASKIN UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF: PROF. EITAN BAR-YOSEF Signature of student: ________________ Date: _________ Signature of supervisor: Date: 08/02/2015 Signature of chairperson of the committee for graduate studies: _______________ Date: _________ November 2014 Acknowledgements I would like to thank the McDonald's Committee, whose avid engagement inspired this project. My gratitude also goes to Prof. Eitan Bar-Yosef, Mrs. Elena Pilehin, and Mr. Sagi Felendler, for their incessant support and encouragement. This work is dedicated to Mr. Mark Khaskin. Abstract This thesis will examine vampire literature from the end of the nineteenth century to the 2000s. I argue that substantial aspects of the generic discourse of this literature have been influenced by the contemporaneously active feminist movements, and that the changes undergone by the vampire figure and its mythology reflect changes within each of the three waves of feminism to be discussed in this thesis. I will begin my discussion with an analysis of Bram Stoker's Dracula, which has drawn ample critical attention in this context by its engagement with the figure of the New Woman, the face of first wave feminism in the United Kingdom of the nineteenth century fin de siècle. -

J. M. COETZEE: ETHICS, SUBALTERNITY, and the CRITIQUE of HUMANISM by Deepa Jani B. A. in English, University of Pune, India

J. M. COETZEE: ETHICS, SUBALTERNITY, AND THE CRITIQUE OF HUMANISM by Deepa Jani B. A. in English, University of Pune, India, 1993 M. A. in English, Carnegie Mellon University, 2003 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English University of Pittsburgh 2013 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Deepa Jani It was defended on April 10, 2013 and approved by Jonathan Arac, Andrew W. Mellon Professor, English John Beverley, Distinguished Professor, Hispanic Languages & Literatures Ronald Judy, Professor, English Marcia Landy, Distinguished Professor, English Dissertation Advisor: Paul A. Bové, Distinguished Professor, English ii Copyright © by Deepa Jani 2013 iii Dedicated to the memory of my father. iv J. M. COETZEE: ETHICS, SUBALTERNITY, AND THE CRITIQUE OF HUMANISM Deepa Jani, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2013 In the era of globalization, postcolonial studies is again confronted with the question of Western humanism and its attendant project of universalizing Eurocentric assumptions about the human. My dissertation argues that J. M. Coetzee’s postmodern novels deliberately reconstruct a literary genealogy of this project from the colonial through the postcolonial periods in order to disrupt it. My thesis addresses four novels of Coetzee that cover his entire oeuvre: the early novel Waiting for the Barbarians (1980), the novel of the middle phase Foe (1986), and the later novels— Disgrace (1999) and Diary of a Bad Year (2007). Each chapter elaborates on the intertextual nature of Coetzee’s novels and explores the rich dialogue between him and the canonical Western writers—Daniel Defoe, Franz Kafka, and Michel de Montaigne. -

A Study of the Theory and Practice of Fiction in the Conrad-Ford

SHE RICE IHSSISUSE A SSUDX OF SHE SHEORX MID PRAGSICE OF FICSIOE II SHE COIBAD-FOKD GOLMBORASIOI toy Pat Moore A SHESIS SUBMISSED SO SHE FACULSX III PABSIAL FULFILLMEHS OF SHE REQDIREMEISS FOB SHE DEGREE OF MASSER OF ARSS Houston, Se&as May 1955 C /4/*fr+wrS: J$>r /<s£f*£> SABLE OF C0HTEET3 Page I, Introduction 1 II. The Combined Theory of Conrad and Ford 00699009 5 IXJL• The Inheritors .«... * 19 IV. Romance 6»06066O66*966O6»«666O666<9eO9*O*966O6«6 46 ¥• ghe Hature off a Grime * * 0 • 00 * 0 • * * 00*•*o«•«*•0** 75 VX 0 COXXGlUBXOn **«a«»«»<»ia«09*«p«9»e»«9«4tt#64««900«0 33 HOteS OO6«66060OO96609O»«696«OO6«99OO«OOOO0eO»* BoXCCtiOd BXbXlO^PEpliy O6«rO©C9<)OO6O406O6»««©«d9O 101 I On October 28, 1898, in a letter to John Galsworthy, Joseph Conrad wrote, "I concluded arrangements for col¬ laboration with Hueffer. He was pleased. I think it's all right.”1 Thus in 1898, following an introduction of the two authors by Edward Garnett, began a ten year col¬ laboration between Ford Madox Hueffer, later Ford, and Joseph Conrad, The two authors wrote together and conversed con¬ stantly during the early years of the collaboration. They lived at each other's homes, made joint Continental trips for the purpose of writing, and traded their individual circles of friends. Ford speaks of their continual ren¬ dering of descriptions as they drove along country lanes by voicing the images in French, translating this into English, then translating the English phrase into French 2 again.