The Angel of Ferrara

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Venice's Marriage to the Sea Blog Post by Jeanne Willoz-Egnor

Venice’s Marriage to the Sea Blog post by Jeanne Willoz-Egnor published May 31, 2019 This weekend marks the annual Festa della Sensa in Venice. Although the festival didn’t start until 1965 it commemorates and recreates the ancient traditional ceremony of Sposalizio del Mar, the event in which Venice is symbolically married to the sea. Hand-colored copperplate engraving titled The Doge in the Bucintoro Departing for the Porto di Lido on Ascension Day. The original artwork was created by Canaletto and engraved by Giovanni Battista Brustolo. This third state engraving was printed by Teodoro Viera in Venice sometime around 1787. [Accession# LE 831] The origins of the ceremony date to the period when Venice was a sovereign state (from 697 AD to 1797 AD). It commemorates two important events in the state’s history: the May 9, 1000 departure of Doge Pietro II Orseolo with a fleet on the successful mission to subdue Narentine pirates threatening Venetian power, trade and travel on the Adriatic and Doge Sebastiano Ziani’s successful negotiation of the Treaty of Venice in 1177. The treaty ended a long standing conflict between the Holy Roman Empire headed by Frederick Barbarossa and the Papacy. Following Orseolo’s victory, each year on Ascension Day Venice celebrated the Doge’s conquest of Dalmatia with a solemn procession of boats led by the doge’s maestà nave to the San Pietro di Castello where the Bishop blessed the doge. The procession then proceeded to the lido at San Nicolò, Venice’s entrée to the Adriatic Sea, where the prayer "for us and all who sail thereon, may the sea be calm and quiet" was offered. -

Rodney Stone

RODNEY STONE PREFACE Amongst the books to which I am indebted for my material in my endeavour to draw various phases of life and character in England at the beginning of the century, I would particularly mention Ashton’s “Dawn of the Nineteenth Century;” Gronow’s “Reminiscences;” Fitzgerald’s “Life and Times of George IV.;” Jesse’s “Life of Brummell;” “Boxiana;” “Pugilistica;” Harper’s “Brighton Road;” Robinson’s “Last Earl of Barrymore” and “Old Q.;” Rice’s “History of the Turf;” Tristram’s “Coaching Days;” James’s “Naval History;” Clark Russell’s “Collingwood” and “Nelson.” I am also much indebted to my friends Mr. J. C. Parkinson and Robert Barr for information upon the subject of the ring. A. CONAN DOYLE. HASLEMERE, September 1, 1896. CHAPTER I - FRIAR’S OAK On this, the first of January of the year 1851, the nineteenth century has reached its midway term, and many of us who shared its youth have already warnings which tell us that it has outworn us. We put our grizzled heads together, we older ones, and we talk of the great days that we have known; but we find that when it is with our children that we talk it is a hard matter to make them understand. We and our fathers before us lived much the same life, but they with their railway trains and their steamboats belong to a different age. It is true that we can put history-books into their hands, and they can read from them of our weary struggle of two and twenty years with that great and evil man. -

141715236.Pdf

This issue of the Other Press has been brought to you by these people (and others) · Don't you love them so? Table Cont 28 30 , Georwe s Malady· Now if :r: could just prowam t ·his VCR to tape "Friends." - I guess it had to happen. The deli tions of its members." This is not At worst, when foisting spurious O where I go for sandwiches has a to say that he did not cherish propaganda, mission statements ~ mission statement. Posted in billboard such beliefs, only that he was too are misleading. At best, they are +-' proportions behind the counter, where busy eradicating a disease to superfluous. One local retail outlet, the menu should be, is their corporate embroider the words on a doily in a "statement of core values" C manifesto, replete with such feel-good and have them framed. issued to its employees, imparts 0 sentiments as "We recognize and But we Jive in a time when the stunning revelation, "We respect the rights of others" and "We humility and quiet accomplish recognize that profitability is · acknowledge the diversity in our ment are seen as weaknesses, essential to our success." Well, U community." The poor harried em when enterprising executroids duh. Might as well include the part C ployee making my sandwich behind buy off-the-rack personalities about opening the doors. As for the counter was so busy respecting . from Tony Robbins and other the respect-the-rights-of-others 0 rights and acknowledging diversity such snake oil salesmen, when type of statements, these are •- that he forgot the mustard. -

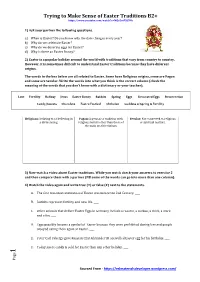

Trying to Make Sense of Easter Traditions B2+

Trying to Make Sense of Easter Traditions B2+ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MQz2mF3jDMc 1) Ask your partner the following questions. a) When is Easter? Do you know why the date changes every year? b) Why do we celebrate Easter? c) Why do we decorate eggs for Easter? d) Why is there an Easter Bunny? 2) Easter is a popular holiday around the world with traditions that vary from country to country. However, it is sometimes difficult to understand Easter traditions because they have different origins. The words in the box below are all related to Easter. Some have Religious origins, some are Pagan and some are Secular. Write the words into what you think is the correct column (check the meaning of the words that you don’t know with a dictionary or your teacher). Lent Fertility Holiday Jesus Easter Bunny Rabbits Spring Eggs Decorated Eggs Resurrection Candy/Sweets Chocolate Eostre Festival Christian Goddess of Spring & Fertility Religious: Relating to or believing in Pagan: A person or tradition with Secular: Not connected to religious a divine being. religious beliefs other than those of or spiritual matters. the main world religions. 3) Now watch a video about Easter traditions. While you watch check your answers to exercise 2 and then compare them with a partner (NB some of the words can go into more than one column). 4) Watch the video again and write true (T) or false (F) next to the statements. A. The first recorded celebration of Easter was before the 2nd Century. ____ B. Rabbits represent fertility and new life. -

Stranieri, Barbari, Migranti: Il Racconto Della Storia Per Comprendere Il Presente

BiBlioteca NazioNale MarciaNa StraNieri, BarBari, MigraNti: il raccoNto della Storia per coMpreNdere il preSeNte Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, Venezia, 2016 1 A Valeria Solesin BiBlioteca NazioNale MarciaNa StraNieri, BarBari, MigraNti: il raccoNto della Storia per coMpreNdere il preSeNte testi di Claudio Azzara, Ermanno Orlando, Lucia Nadin, Reinhold C. Mueller, Giuseppina Minchella, Vera Costantini, Andrea Zannini, Mario Infelise, Piero Brunello, Piero Lando a cura di Tiziana Plebani Venezia, Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, 2016 ideazione Tiziana Plebani in copertina Venezia, Palazzo Ducale, Capitello dei popoli delle nazioni del mondo finito di stampare dicembre 2016 La Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana ha inteso, con questa pubblica- zione, documentare i contributi presentati nel corso del ciclo Stranieri, barbari, migranti: il racconto della storia per comprendere il presente, ideato e curato nel 2016 da Tiziana Plebani. Un sentito ringraziamento va, oltre alla curatrice e al personale della Biblioteca, che hanno reso possibile la realizzazione degli eventi, ai singoli relatori che hanno generosamente accettato in tempi brevissimi di trasporre in forma scritta una sintesi di quanto avevano esposto nel corso degli incontri. Grazie anche a Scrinium S.p.a., partner della Marciana in iniziative di altissimo profilo, dalla significativa collaborazione all’Anno manu- ziano del 2015 alla realizzazione del facsimile del Testamento di Marco Polo, corredato da un importante volume di studi, per il sostegno finan- ziario alla pubblicazione. Maurizio Messina Direttore della Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana iNdice Tiziana Plebani preSeNtazioNe 11 Claudio Azzara BarBari 13 Ermanno Orlando MiNoraNze, MigraNti e MatriMoNi a VeNezia Nel BaSSo MedioeVo 17 Lucia Nadin StraNieri di caSa: gli alBaNeSi a VeNezia (xV-xVi Sec.) 23 Reinhold C. -

Wednesday Reflection: Rabbits

Wednesday Reflection: Rabbits Over the past few weeks I have been reflecting on visitors to the manse garden, including hedgehogs, butterflies, bats and fairies. Towards evening, we are blessed with an occasional visit from rabbits. Quietly, they sneak under the fence and stand motionless, poised in the middle of the lawn. The moment the spot me watching them they dart out of sight with immense speed. What might we say of rabbits in the Christian tradition? Dating from the Mediaeval period, many churches have rabbits carved into the stonework. Rabbits and hares were often depicted interchangeably. Three hares sharing ears between them artistically represent the Holy Trinity: Father, Son and Holy Spirit. There is an excellent example of this in Paderborn Cathedral in Germany. In his painting Agony in the Garden, the Italian artist, Andrea Mantegna, portrays the suffering of Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane. The disciples lie asleep while Christ prays on an elevated rock. The imposing walls of the city of Jerusalem can be seen in the background. Under the night sky, three rabbits conspicuously sit on the path which meanders through the garden. A symbol of the Trinity, one of the rabbits makes its way to be with Jesus; this is the Second Person of the Trinity. Elsewhere in Christianity, rabbits are a symbol of sin. In Wimborne Minster in Dorset, there are two ornate stone corbels. In the first, a rabbit is in the mouth of a hound and, in the second, a rabbit is being hunted by a hawk. In both cases, these images represent Christ hunting sin. -

Bodies of Knowledge: the Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2015 Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600 Geoffrey Shamos University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Shamos, Geoffrey, "Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600" (2015). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1128. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1128 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1128 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600 Abstract During the second half of the sixteenth century, engraved series of allegorical subjects featuring personified figures flourished for several decades in the Low Countries before falling into disfavor. Designed by the Netherlandsâ?? leading artists and cut by professional engravers, such series were collected primarily by the urban intelligentsia, who appreciated the use of personification for the representation of immaterial concepts and for the transmission of knowledge, both in prints and in public spectacles. The pairing of embodied forms and serial format was particularly well suited to the portrayal of abstract themes with multiple components, such as the Four Elements, Four Seasons, Seven Planets, Five Senses, or Seven Virtues and Seven Vices. While many of the themes had existed prior to their adoption in Netherlandish graphics, their pictorial rendering had rarely been so pervasive or systematic. -

The Angel of Ferrara

The Angel of Ferrara Benjamin Woolley Goldsmith’s College, University of London Submitted for the degree of PhD I declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own Benjamin Woolley Date: 1st October, 2014 Abstract This thesis comprises two parts: an extract of The Angel of Ferrara, a historical novel, and a critical component entitled What is history doing in Fiction? The novel is set in Ferrara in February, 1579, an Italian city at the height of its powers but deep in debt. Amid the aristocratic pomp and popular festivities surrounding the duke’s wedding to his third wife, the secret child of the city’s most celebrated singer goes missing. A street-smart debt collector and lovelorn bureaucrat are drawn into her increasingly desperate attempts to find her son, their efforts uncovering the brutal instruments of ostentation and domination that gave rise to what we now know as the Renaissance. In the critical component, I draw on the experience of writing The Angel of Ferrara and nonfiction works to explore the relationship between history and fiction. Beginning with a survey of the development of historical fiction since the inception of the genre’s modern form with the Walter Scott’s Waverley, I analyse the various paratextual interventions—prefaces, authors’ notes, acknowledgements—authors have used to explore and explain the use of factual research in their works. I draw on this to reflect in more detail at how research shaped the writing of the Angel of Ferrara and other recent historical novels, in particular Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall. -

Throbbing Gristle’S Late Performances

Guaranteeing Disappointment: Time, Culture, and Transgression in the Context of Throbbing Gristle’s Late Performances. Clint McCallum June 2008 I don't think there's any point in doing anything unless you push yourself. When in doubt--be extreme. -Genesis P-Orridge (Ford, 6.31) Pretty much EVERYONE who pertains to be 'Industrial' has completely missed the point and take the term 'Industrial' far too literally. For us in the 70s'-80s' it was a way of life, a certain mindset and attitude of non-conformity. We were anti- facists, anti-communist, anti-music industry and anti-government. We still are. Industrial Music as a genre has become a Frankenstein's monster and bears no relationship to what we started in the 1970s'. It has become just another metal bashing sub-genre of goth, punk and rock. -Chris Carter (http://www.ikonen-magazin.de/interview/TG.htm) One of the things about Gristle I think, is that we're pretty careful to make sure that we're not lured by the kinda star thing. In fact if there's one single mistake that most bands make, it is their fundamental and underneath, their desire to become rock stars, the same as all the other people, no matter how much they might claim that they don't. The Devos and the Pere Ubu's of this world really want to be rock stars and that's not necessarily a bad thing if that is your intent, if you say 'I'm going to be a rock star and I'm going to do it by making groovy catchy records' there's nothing the matter with making groovy catchy records, but if you do it at the same time as you're saying you're doing something that's socially important and meaningful, then that's trades description act as far as I'm concerned. -

Historical Perspectives of Sports Tourism

Journal of Sport Tourism 9(1), 2004, 5–101 Historical perspectives of sports tourism John Zauhar Sport Tourism International Council .................................................................................................................................... PREAMBLE ‘In 1992, there were 1.3 million people arriving in a country outside that of their residence and spending an average of $764 million on accommodations, meals, entertainment and shopping’ (Segal, 1987). Total international tourist arrivals for 1989 have been established by the World Tourism Organization (WTO) at 405.3 million. And travel and tourism contribution to the world economy amounted to $US2 trillion in sales. In effect, the European Council on Development has deter- mined that, by the year 2000, the tourism industry will be the largest in the world (World Tourism Organization, 1994). Whereas in previous decades tourism has been largely shaped by transport technol- ogy advances, the future decade will be determined by a number of factors, already evidenced: socio-demographic changes; electronic information and communication systems; more knowledgeable and demanding consumers; de-regulatory market place (Fridgen, 1991: 3–26). Some influences on, and determinants of, tourism activity in the 1990-2000 period will be: the scale and variety of tourism development in all types of tourism destinations; the growing interest in peoples and cultures of developing countries; increases in the number of consumers with free time, financial ability and interest to travel; the growing importance of ethnic ties between different nations. Prime examples of market niche targeting related to sports, according to the WTO forecast, are: sailing, yachting, scuba diving, golfing, resort holidays and island hopping. Themed holidays are also becoming popular, accounting for a significant proportion of total tourist demands – approaching the stage of mainstream holiday rather than the traditional ‘beach’ sequence (McCourt, 1989: 13). -

Entertainment Plus Karaoke by Title

Entertainment Plus Karaoke by Title #1 Crush 19 Somethin Garbage Wills, Mark (Can't Live Without Your) Love And 1901 Affection Phoenix Nelson 1969 (I Called Her) Tennessee Stegall, Keith Dugger, Tim 1979 (I Called Her) Tennessee Wvocal Smashing Pumpkins Dugger, Tim 1982 (I Just) Died In Your Arms Travis, Randy Cutting Crew 1985 (Kissed You) Good Night Bowling For Soup Gloriana 1994 0n The Way Down Aldean, Jason Cabrera, Ryan 1999 1 2 3 Prince Berry, Len Wilkinsons, The Estefan, Gloria 19th Nervous Breakdown 1 Thing Rolling Stones Amerie 2 Become 1 1,000 Faces Jewel Montana, Randy Spice Girls, The 1,000 Years, A (Title Screen 2 Becomes 1 Wrong) Spice Girls, The Perri, Christina 2 Faced 10 Days Late Louise Third Eye Blind 20 Little Angels 100 Chance Of Rain Griggs, Andy Morris, Gary 21 Questions 100 Pure Love 50 Cent and Nat Waters, Crystal Duets 50 Cent 100 Years 21st Century (Digital Boy) Five For Fighting Bad Religion 100 Years From Now 21st Century Girls Lewis, Huey & News, The 21st Century Girls 100% Chance Of Rain 22 Morris, Gary Swift, Taylor 100% Cowboy 24 Meadows, Jason Jem 100% Pure Love 24 7 Waters, Crystal Artful Dodger 10Th Ave Freeze Out Edmonds, Kevon Springsteen, Bruce 24 Hours From Tulsa 12:51 Pitney, Gene Strokes, The 24 Hours From You 1-2-3 Next Of Kin Berry, Len 24 K Magic Fm 1-2-3 Redlight Mars, Bruno 1910 Fruitgum Co. 2468 Motorway 1234 Robinson, Tom Estefan, Gloria 24-7 Feist Edmonds, Kevon 15 Minutes 25 Miles Atkins, Rodney Starr, Edwin 16th Avenue 25 Or 6 To 4 Dalton, Lacy J. -

3500 ¥25000 ¥2000 ¥4000 ¥10000 ¥4000 ¥3500 ¥3000 ¥5000 ¥5000

ARTHUR RUSSELL ARTHUR RUSSELL BAUHAUS COCTEAU TWINS COCTEAU TWINS World Of Echo First Thought Best Thought In The Flat Field Four-Calendar café Milk & Kisses ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 1986年 UPSIDE 【UP600091】 2006年 AUDIKA 【AU10051】 1980年 4AD 【CAD13】 1993年 FONTANA 【5182591】 1996年 FONTANA 【5145011】 US ORIGNAL LP US ORIGNAL 3LP UK ORIGINAL LP UK ORIGINAL LP UK ORIGINAL LP SHRINK STICKER INNER SLEEVE INNER SLEEVE INNER SLEEVE INNER SLEEVE 買取 買取 買取 買取 買取 価格 ¥5,000 価格 ¥6,000 価格 ¥1,500 価格 ¥6,000 価格 ¥8,000 CONTORTIONS CURE CURE CURE CURE BUY Kiss Me Kiss Me Kiss Me Disintegration Wish Show ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 1979年 ZE 【ZE33002】 1987年 FICTION 【FIXH13】 1989年 FICTION 【FIXH14】 1992年 FICTION 【FIXH20】 1993年 FICTION 【FIXH25】 US ORIGNAL LP UK ORIGINAL 2LP UK ORIGINAL LP UK ORIGINAL 2LP UK ORIGINAL 2LP INNER SLEEVE / INSERT INNER SLEEVE INNER SLEEVE INNER SLEEVE 買取 買取 買取 買取 買取 価格 ¥2,000 価格 ¥2,000 価格 ¥2,000 価格 ¥6,000 価格 ¥3,500 CURE CURE CURE DAVID CUNNINGHAM DAVID SYLVIAN Paris Wild Mood Swings Bloodflowers Grey Scale Blemish ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 1993年 FICTION 【FIXH26】 1996年 FICTION 【FIXLP28】 2000年 FICTION 【FIX31】 1977年 PIANO 【PIANO001】 2004年 SAMADHISOUND 【SOUNDLP001】 UK ORIGINAL 2LP UK ORIGINAL 2LP UK ORIGINAL 2LP UK ORIGINAL LP UK&US ORIGINAL LP INNER SLEEVE INNER SLEEVE INSERT INSERT 買取 買取 買取 買取 買取 価格 ¥12,000 価格 ¥6,500 価格 ¥10,000 価格 ¥2,000 価格 ¥6,000 DAVID SYLVIAN DEAD CAN DANCE DEPECHE MODE DEPECHE MODE DNA Manafon Into The Labyrinth Violator Playing The Angel A Taste Of DNA ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 2010年 SAMADHISOUND 【SOUNDLP002】 1993年 4AD 【DAD3013】 1990年 MUTE