CS151.02 2007S : Character Values in Scheme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ogham-Runes and El-Mushajjar

c L ite atu e Vo l x a t n t r n o . o R So . u P R e i t ed m he T a s . 1 1 87 " p r f ro y f r r , , r , THE OGHAM - RUNES AND EL - MUSHAJJAR A D STU Y . BY RICH A R D B URTO N F . , e ad J an uar 22 (R y , PART I . The O ham-Run es g . e n u IN tr ating this first portio of my s bj ect, the - I of i Ogham Runes , have made free use the mater als r John collected by Dr . Cha les Graves , Prof. Rhys , and other students, ending it with my own work in the Orkney Islands . i The Ogham character, the fair wr ting of ' Babel - loth ancient Irish literature , is called the , ’ Bethluis Bethlm snion e or , from its initial lett rs, like “ ” Gree co- oe Al hab e t a an d the Ph nician p , the Arabo “ ” Ab ad fl d H ebrew j . It may brie y be describe as f b ormed y straight or curved strokes , of various lengths , disposed either perpendicularly or obliquely to an angle of the substa nce upon which the letters n . were i cised , punched, or rubbed In monuments supposed to be more modern , the letters were traced , b T - N E E - A HE OGHAM RU S AND L M USH JJ A R . n not on the edge , but upon the face of the recipie t f n l o t sur ace ; the latter was origi al y wo d , s aves and tablets ; then stone, rude or worked ; and , lastly, metal , Th . -

Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 a Study for the Library of Congress

1 Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 A Study for the Library of Congress Part 1: New Scripts Jack Cain Senior Consultant Trylus Computing, Toronto 1 Purpose This assessment intends to study the issues and make recommendations on the possible expansion of the character set repertoire for bibliographic records in MARC21 format. 1.1 “Encoding Scheme” vs. “Repertoire” An encoding scheme contains codes by which characters are represented in computer memory. These codes are organized according to a certain methodology called an encoding scheme. The list of all characters so encoded is referred to as the “repertoire” of characters in the given encoding schemes. For example, ASCII is one encoding scheme, perhaps the one best known to the average non-technical person in North America. “A”, “B”, & “C” are three characters in the repertoire of this encoding scheme. These three characters are assigned encodings 41, 42 & 43 in ASCII (expressed here in hexadecimal). 1.2 MARC8 "MARC8" is the term commonly used to refer both to the encoding scheme and its repertoire as used in MARC records up to 1998. The ‘8’ refers to the fact that, unlike Unicode which is a multi-byte per character code set, the MARC8 encoding scheme is principally made up of multiple one byte tables in which each character is encoded using a single 8 bit byte. (It also includes the EACC set which actually uses fixed length 3 bytes per character.) (For details on MARC8 and its specifications see: http://www.loc.gov/marc/.) MARC8 was introduced around 1968 and was initially limited to essentially Latin script only. -

418338 1 En Bookbackmatter 205..225

Glossary Abhayamudra A style of keeping hands while sitting Abhidhama The Abhidhamma Pitaka is a detailed scholastic reworking of material appearing in the Suttas, according to schematic classifications. It does not contain systematic philosophical treatises, but summaries or enumerated lists. The other two collections are the Sutta Pitaka and the Vinaya Pitaka Abhog It is the fourth part of a composition. The last movement gradually goes back to the sthayi after completion of the paraphrasing and improvisation of the composition, which can cover even three octaves in the recital of a master performer Acharya A teacher or a tutor who is the symbol of wisdom Addhayoga One of seven kinds of lodgings where monks are allowed to live. Addhayoga is a building with a roof sloping on either one side or both. It is shaped like wings of the Garuda Agganna-sutta AggannaSutta is the 27th Sutta of the Digha Nikaya collection. The sutta describes a discourse imparted by the Buddha to two Brahmins, Bharadvaja, and Vasettha, who left their family and caste to become monks Ahankar Haughtiness, self-importance A-hlu-khan mandap Burmese term, a temporary pavilion to receive donation Akshamala A japa mala or mala (meaning garland) which is a string of prayer beads commonly used by Hindus, Buddhists, and some Sikhs for the spiritual practice known in Sanskrit as japa. It is usually made from 108 beads, though other numbers may also be used Amulets An ornament or small piece of jewellery thought to give protection against evil, danger, or disease. Clay tablets have also been used as amulets. -

Bbedit 13.5 User Manual

User Manual BBEdit™ Professional Code and Text Editor for the Macintosh Bare Bones Software, Inc. ™ BBEdit 13.5 Product Design Jim Correia, Rich Siegel, Steve Kalkwarf, Patrick Woolsey Product Engineering Jim Correia, Seth Dillingham, Matt Henderson, Jon Hueras, Steve Kalkwarf, Rich Siegel, Steve Sisak Engineers Emeritus Chris Borton, Tom Emerson, Pete Gontier, Jamie McCarthy, John Norstad, Jon Pugh, Mark Romano, Eric Slosser, Rob Vaterlaus Documentation Fritz Anderson, Philip Borenstein, Stephen Chernicoff, John Gruber, Jeff Mattson, Jerry Kindall, Caroline Rose, Allan Rouselle, Rich Siegel, Vicky Wong, Patrick Woolsey Additional Engineering Polaschek Computing Icon Design Bryan Bell Factory Color Schemes Luke Andrews Additional Color Schemes Toothpaste by Cat Noon, and Xcode Dark by Andrew Carter. Used by permission. Additional Icons By icons8. Used under license Additional Artwork By Jonathan Hunt PHP keyword lists Contributed by Ted Stresen-Reuter. Previous versions by Carsten Blüm Published by: Bare Bones Software, Inc. 73 Princeton Street, Suite 206 North Chelmsford, MA 01863 USA (978) 251-0500 main (978) 251-0525 fax https://www.barebones.com/ Sales & customer service: [email protected] Technical support: [email protected] BBEdit and the BBEdit User Manual are copyright ©1992-2020 Bare Bones Software, Inc. All rights reserved. Produced/published in USA. Copyrights, Licenses & Trademarks cmark ©2014 by John MacFarlane. Used under license; part of the CommonMark project LibNcFTP Used under license from and copyright © 1996-2010 Mike Gleason & NcFTP Software Exuberant ctags ©1996-2004 Darren Hiebert (source code here) PCRE2 Library Written by Philip Hazel and Zoltán Herczeg ©1997-2018 University of Cambridge, England Info-ZIP Library ©1990-2009 Info-ZIP. -

DFDL WG Stephen M Hanson, IBM [email protected] September 2014

GFD-P-R.207 (OBSOLETED by GFD-P-R.240) Michael J Beckerle, Tresys Technology OGF DFDL WG Stephen M Hanson, IBM [email protected] September 2014 Data Format Description Language (DFDL) v1.0 Specification Status of This Document Grid Final Draft (GFD) Obsoletes This document obsoletes GFD-P-R.174 dated January 2011 [OBSOLETE_DFDL]. Copyright Notice Copyright © Global Grid Forum (2004-2006). Some Rights Reserved. Distribution is unlimited. Copyright © Open Grid Forum (2006-2014). Some Rights Reserved. Distribution is unlimited Abstract This document is OBSOLETE. It is superceded by GFD-P-R.240. This document provides a definition of a standard Data Format Description Language (DFDL). This language allows description of text, dense binary, and legacy data formats in a vendor- neutral declarative manner. DFDL is an extension to the XML Schema Description Language (XSDL). GFD-P-R.207 (OBSOLETED by GFD-P-R.240) September 2014 Contents Data Format Description Language (DFDL) v1.0 Specification ...................................................... 1 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 9 1.1 Why is DFDL Needed? ................................................................................................... 10 1.2 What is DFDL? ................................................................................................................ 10 Simple Example ...................................................................................................... -

An Introduction to Old Persian Prods Oktor Skjærvø

An Introduction to Old Persian Prods Oktor Skjærvø Copyright © 2016 by Prods Oktor Skjærvø Please do not cite in print without the author’s permission. This Introduction may be distributed freely as a service to teachers and students of Old Iranian. In my experience, it can be taught as a one-term full course at 4 hrs/w. My thanks to all of my students and colleagues, who have actively noted typos, inconsistencies of presentation, etc. TABLE OF CONTENTS Select bibliography ................................................................................................................................... 9 Sigla and Abbreviations ........................................................................................................................... 12 Lesson 1 ..................................................................................................................................................... 13 Old Persian and old Iranian. .................................................................................................................... 13 Script. Origin. .......................................................................................................................................... 14 Script. Writing system. ........................................................................................................................... 14 The syllabary. .......................................................................................................................................... 15 Logograms. ............................................................................................................................................ -

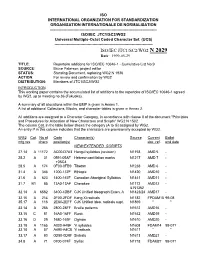

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N 2029 Date: 1999-05-29

ISO INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR STANDARDIZATION ORGANISATION INTERNATIONALE DE NORMALISATION --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set (UCS) -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N 2029 Date: 1999-05-29 TITLE: Repertoire additions for ISO/IEC 10646-1 - Cumulative List No.9 SOURCE: Bruce Paterson, project editor STATUS: Standing Document, replacing WG2 N 1936 ACTION: For review and confirmation by WG2 DISTRIBUTION: Members of JTC1/SC2/WG2 INTRODUCTION This working paper contains the accumulated list of additions to the repertoire of ISO/IEC 10646-1 agreed by WG2, up to meeting no.36 (Fukuoka). A summary of all allocations within the BMP is given in Annex 1. A list of additional Collections, Blocks, and character tables is given in Annex 2. All additions are assigned to a Character Category, in accordance with clause II of the document "Principles and Procedures for Allocation of New Characters and Scripts" WG2 N 1502. The column Cat. in the table below shows the category (A to G) assigned by WG2. An entry P in this column indicates that the characters are provisionally accepted by WG2. WG2 Cat. No of Code Character(s) Source Current Ballot mtg.res chars position(s) doc. ref. end date NEW/EXTENDED SCRIPTS 27.14 A 11172 AC00-D7A3 Hangul syllables (revision) N1158 AMD 5 - 28.2 A 31 0591-05AF Hebrew cantillation marks N1217 AMD 7 - +05C4 28.5 A 174 0F00-0FB9 Tibetan N1238 AMD 6 - 31.4 A 346 1200-137F Ethiopic N1420 AMD10 - 31.6 A 623 1400-167F Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics N1441 AMD11 - 31.7 B1 85 13A0-13AF Cherokee N1172 AMD12 - & N1362 32.14 A 6582 3400-4DBF CJK Unified Ideograph Exten. -

1 Working Draft for Supporting Blueberry Revision of XML

Working Draft for Supporting Blueberry Revision of XML Recommendation (1.0) with Particular Emphasis on Ethiopic Script and Writing System November 2001 This Version: http://www.digitaladdis.com/sk/ Ethiopics XML_Proposal_Version1.pdf Latest Ver.: http://www.digitaladdis.com/sk/ Ethiopics XML_Proposal_Version1.pdf Authors/Editors: Samuel Kinde Kassegne (Nanogen, UC San Diego, Engg Ext.) <[email protected]> Bibi Ephraim (Hewlett Packard) <[email protected]> Copyright ©2001, SKK, BE. Working Draft for Supporting Blueberry Revision of XML - Ethiopics Script 1 Abstract This document contains XML example codes, surveys and recommendations that support the need for Ethiopic script-based XML element type and attribute names in Amharic, Afaan Oromo, Tigrigna, Agewgna, Guragina, Hadiya, Harari, Sidama, Kembatigna and other Ethiopian languages that use Ethiopic script. Status of this Document This document is an initial working draft that is to be widely circulated for comment from the Ethiopic XML Interest Group and the wider public. The document is a work in progress. Table of Contents 1. Scope 2. Introduction 3. Objective 4. Review of Status of Native HTML and XML Applications in Ethiopic 4.1. Evolution of Ethiopic Content in HTML 4.2. Ethiopic and XML 5. Hybrid XML Document Markups in Ethiopic 5.1. Examples 5.2. Discussions 6. Fully-Native XML Document Markups in Ethiopic 6.1. Examples 6.2. Discussions 7. Conclusions and Recommendations 8. Appendix 9. References Working Draft for Supporting Blueberry Revision of XML - Ethiopics Script 2 1. Scope The work reported in this document contains XML example codes, surveys and recommendations that support the need for a revision of current XML standards to allow Ethiopic-based XML element type and attribute names in Amharic, Afaan Oromo, Tigrigna, Agewgna, Guragina, Hadiya, Harari, Sidama, Kembatigna and other Ethiopian languages that use Ethiopic script. -

Greek Alphabet ( ) Ελληνικ¿ Γρ¿Μματα

Greek alphabet and pronunciation 9/27/05 12:01 AM Writing systems: abjads | alphabets | syllabic alphabets | syllabaries | complex scripts undeciphered scripts | alternative scripts | your con-scripts | A-Z index Greek alphabet (ελληνικ¿ γρ¿μματα) Origin The Greek alphabet has been in continuous use for the past 2,750 years or so since about 750 BC. It was developed from the Canaanite/Phoenician alphabet and the order and names of the letters are derived from Phoenician. The original Canaanite meanings of the letter names was lost when the alphabet was adapted for Greek. For example, alpha comes for the Canaanite aleph (ox) and beta from beth (house). At first, there were a number of different versions of the alphabet used in various different Greek cities. These local alphabets, known as epichoric, can be divided into three groups: green, blue and red. The blue group developed into the modern Greek alphabet, while the red group developed into the Etruscan alphabet, other alphabets of ancient Italy and eventually the Latin alphabet. By the early 4th century BC, the epichoric alphabets were replaced by the eastern Ionic alphabet. The capital letters of the modern Greek alphabet are almost identical to those of the Ionic alphabet. The minuscule or lower case letters first appeared sometime after 800 AD and developed from the Byzantine minuscule script, which developed from cursive writing. Notable features Originally written horizontal lines either from right to left or alternating from right to left and left to right (boustophedon). Around 500 BC the direction of writing changed to horizontal lines running from left to right. -

Pronunciation

PRONUNCIATION Guide to the Romanized version of quotations from the Guru Granth Saheb. A. Consonants Gurmukhi letter Roman Word in Roman Word in Gurmukhi Meaning Letter letters using the letters using the relevant letter relevant letter from from the second the first column column S s Sabh sB All H h Het ihq Affection K k Krodh kroD Anger K kh Khayl Kyl Play G g Guru gurU Teacher G gh Ghar Gr House | ng Ngyani / gyani i|AwnI / igAwnI Possessing divine knowledge C c Cor cor Thief C ch Chaata Cwqw Umbrella j j Jahaaj jhwj Ship J jh Jhaaroo JwVU Broom \ ny Sunyi su\I Quiet t t Tap t`p Jump T th Thag Tg Robber f d Dar fr Fear F dh Dholak Folk Drum x n Hun hux Now q t Tan qn Body Q th Thuk Quk Sputum d d Den idn Day D dh Dhan Dn Wealth n n Net inq Everyday p p Peta ipqw Father P f Fal Pl Fruit b b Ben ibn Without B bh Bhagat Bgq Saint m m Man mn Mind X y Yam Xm Messenger of death r r Roti rotI Bread l l Loha lohw Iron v v Vasai vsY Dwell V r Koora kUVw Rubbish (n) in brackets, and (g) in brackets after the consonant 'n' both indicate a nasalised sound - Eg. 'Tu(n)' meaning 'you'; 'saibhan(g)' meaning 'by himself'. All consonants in Punjabi / Gurmukhi are sounded - Eg. 'pai-r' meaning 'foot' where the final 'r' is sounded. 3 Copyright Material: Gurmukh Singh of Raub, Pahang, Malaysia B. -

Inventory of Romanization Tools

Inventory of Romanization Tools Standards Intellectual Management Office Library and Archives Canad Ottawa 2006 Inventory of Romanization Tools page 1 Language Script Romanization system for an English Romanization system for a French Alternate Romanization system catalogue catalogue Amharic Ethiopic ALA-LC 1997 BGN/PCGN 1967 UNGEGN 1967 (I/17). http://www.eki.ee/wgrs/rom1_am.pdf Arabic Arabic ALA-LC 1997 ISO 233:1984.Transliteration of Arabic BGN/PCGN 1956 characters into Latin characters NLC COPIES: BS 4280:1968. Transliteration of Arabic characters NL Stacks - TA368 I58 fol. no. 00233 1984 E DMG 1936 NL Stacks - TA368 I58 fol. no. DIN-31635, 1982 00233 1984 E - Copy 2 I.G.N. System 1973 (also called Variant B of the Amended Beirut System) ISO 233-2:1993. Transliteration of Arabic characters into Latin characters -- Part 2: Lebanon national system 1963 Arabic language -- Simplified transliteration Morocco national system 1932 Royal Jordanian Geographic Centre (RJGC) System Survey of Egypt System (SES) UNGEGN 1972 (II/8). http://www.eki.ee/wgrs/rom1_ar.pdf Update, April 2004: http://www.eki.ee/wgrs/ung22str.pdf Armenian Armenian ALA-LC 1997 ISO 9985:1996. Transliteration of BGN/PCGN 1981 Armenian characters into Latin characters Hübschmann-Meillet. Assamese Bengali ALA-LC 1997 ISO 15919:2001. Transliteration of Hunterian System Devanagari and related Indic scripts into Latin characters UNGEGN 1977 (III/12). http://www.eki.ee/wgrs/rom1_as.pdf 14/08/2006 Inventory of Romanization Tools page 2 Language Script Romanization system for an English Romanization system for a French Alternate Romanization system catalogue catalogue Azerbaijani Arabic, Cyrillic ALA-LC 1997 ISO 233:1984.Transliteration of Arabic characters into Latin characters. -

A Message from Afar: Fact Sheet 3 (PDF)

3 What’s the Message? Here’s your signal The detection of a signal from another world would be a most remarkable moment in human history. However, if we detect such a signal, is it just a beacon from their technology, without any content, or does it contain information or even a message? Does it resemble sound, or is it like interstellar e-mail? Can we ever understand such a message? This appears to be a tremendous challenge, given that we still have many scripts from our own antiquity that remain undeciphered, despite many serious attempts, over hundreds of years. – And we know far more about humanity than about extra-terrestrial intelligence… We are facing all the complexities involved in understanding and glimpsing the intellect of the author, while the world’s expectations demand immediacy of information. So, where do we begin? Structure and language Information stands out from randomness, it is based on structures. The problem goal we face, after we detect a signal, is to first separate out those information-carrying signals from other phenomena, without being able to engage in a dialogue, and then to learn something about the structure of their content in the passing. This means that we need a suitable filter. We need a way of separating out the interesting stuff; we need a language detector. While identifying the location of origin of a candidate signal can rule out human making, its content could involve a vast array of possible structures, some of which may be beyond our knowledge or imagination; however, for identifying intelligence that shares any pattern with our way of processing and transmitting information, the collective knowledge and examples here on Earth are a good starting point.