Ogam: Archaizing, Orthography and the Authenticity of the Manuscript Key to the Alphabet Author(S): Damian Mcmanus Source: Ériu, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ogham-Runes and El-Mushajjar

c L ite atu e Vo l x a t n t r n o . o R So . u P R e i t ed m he T a s . 1 1 87 " p r f ro y f r r , , r , THE OGHAM - RUNES AND EL - MUSHAJJAR A D STU Y . BY RICH A R D B URTO N F . , e ad J an uar 22 (R y , PART I . The O ham-Run es g . e n u IN tr ating this first portio of my s bj ect, the - I of i Ogham Runes , have made free use the mater als r John collected by Dr . Cha les Graves , Prof. Rhys , and other students, ending it with my own work in the Orkney Islands . i The Ogham character, the fair wr ting of ' Babel - loth ancient Irish literature , is called the , ’ Bethluis Bethlm snion e or , from its initial lett rs, like “ ” Gree co- oe Al hab e t a an d the Ph nician p , the Arabo “ ” Ab ad fl d H ebrew j . It may brie y be describe as f b ormed y straight or curved strokes , of various lengths , disposed either perpendicularly or obliquely to an angle of the substa nce upon which the letters n . were i cised , punched, or rubbed In monuments supposed to be more modern , the letters were traced , b T - N E E - A HE OGHAM RU S AND L M USH JJ A R . n not on the edge , but upon the face of the recipie t f n l o t sur ace ; the latter was origi al y wo d , s aves and tablets ; then stone, rude or worked ; and , lastly, metal , Th . -

Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 a Study for the Library of Congress

1 Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 A Study for the Library of Congress Part 1: New Scripts Jack Cain Senior Consultant Trylus Computing, Toronto 1 Purpose This assessment intends to study the issues and make recommendations on the possible expansion of the character set repertoire for bibliographic records in MARC21 format. 1.1 “Encoding Scheme” vs. “Repertoire” An encoding scheme contains codes by which characters are represented in computer memory. These codes are organized according to a certain methodology called an encoding scheme. The list of all characters so encoded is referred to as the “repertoire” of characters in the given encoding schemes. For example, ASCII is one encoding scheme, perhaps the one best known to the average non-technical person in North America. “A”, “B”, & “C” are three characters in the repertoire of this encoding scheme. These three characters are assigned encodings 41, 42 & 43 in ASCII (expressed here in hexadecimal). 1.2 MARC8 "MARC8" is the term commonly used to refer both to the encoding scheme and its repertoire as used in MARC records up to 1998. The ‘8’ refers to the fact that, unlike Unicode which is a multi-byte per character code set, the MARC8 encoding scheme is principally made up of multiple one byte tables in which each character is encoded using a single 8 bit byte. (It also includes the EACC set which actually uses fixed length 3 bytes per character.) (For details on MARC8 and its specifications see: http://www.loc.gov/marc/.) MARC8 was introduced around 1968 and was initially limited to essentially Latin script only. -

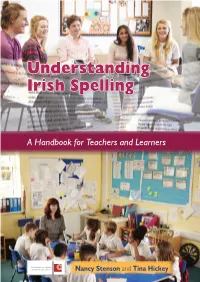

Understanding Irish Spelling

Understanding Irish Spelling A Handbook for Teachers and Learners Nancy Stenson and Tina Hickey Understanding Irish Spelling A Handbook for Teachers and Learners Nancy Stenson and Tina Hickey i © Stenson and Hickey 2018 ii Acknowledgements The preparation of this publication was supported by a grant from An Chomhairle um Oideachas Gaeltachta agus Gaelscolaíochta, and we wish to express our sincere thanks to COGG, and to Muireann Ní Mhóráin and Pól Ó Cainín in particular. We acknowledge most gratefully the support of the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellowship scheme for enabling this collaboration through its funding of an Incoming International Fellowship to the first author, and to UCD School of Psychology for hosting her as an incoming fellow and later an as Adjunct Professor. We also thank the Fulbright Foundation for the Fellowship they awarded to Prof. Stenson prior to the Marie Curie fellowship. Most of all, we thank the educators at first, second and third level who shared their experience and expertise with us in the research from which we draw in this publication. We benefitted significantly from input from many sources, not all of whom can be named here. Firstly, we wish to thank most sincerely all of the participants in our qualitative study interviews, who generously shared their time and expertise with us, and those in the schools that welcomed us to their classrooms and facilitated observation and interviews. We also wish to thank the participants at many conferences, seminars and presentations, particularly those in Bangor, Berlin, Brighton, Hamilton and Ottawa, as well as those in several educational institutions in Ireland who offered comments and suggestions. -

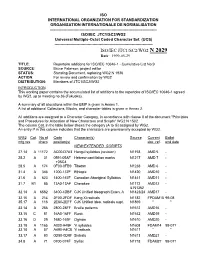

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N 2029 Date: 1999-05-29

ISO INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR STANDARDIZATION ORGANISATION INTERNATIONALE DE NORMALISATION --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set (UCS) -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N 2029 Date: 1999-05-29 TITLE: Repertoire additions for ISO/IEC 10646-1 - Cumulative List No.9 SOURCE: Bruce Paterson, project editor STATUS: Standing Document, replacing WG2 N 1936 ACTION: For review and confirmation by WG2 DISTRIBUTION: Members of JTC1/SC2/WG2 INTRODUCTION This working paper contains the accumulated list of additions to the repertoire of ISO/IEC 10646-1 agreed by WG2, up to meeting no.36 (Fukuoka). A summary of all allocations within the BMP is given in Annex 1. A list of additional Collections, Blocks, and character tables is given in Annex 2. All additions are assigned to a Character Category, in accordance with clause II of the document "Principles and Procedures for Allocation of New Characters and Scripts" WG2 N 1502. The column Cat. in the table below shows the category (A to G) assigned by WG2. An entry P in this column indicates that the characters are provisionally accepted by WG2. WG2 Cat. No of Code Character(s) Source Current Ballot mtg.res chars position(s) doc. ref. end date NEW/EXTENDED SCRIPTS 27.14 A 11172 AC00-D7A3 Hangul syllables (revision) N1158 AMD 5 - 28.2 A 31 0591-05AF Hebrew cantillation marks N1217 AMD 7 - +05C4 28.5 A 174 0F00-0FB9 Tibetan N1238 AMD 6 - 31.4 A 346 1200-137F Ethiopic N1420 AMD10 - 31.6 A 623 1400-167F Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics N1441 AMD11 - 31.7 B1 85 13A0-13AF Cherokee N1172 AMD12 - & N1362 32.14 A 6582 3400-4DBF CJK Unified Ideograph Exten. -

1 Working Draft for Supporting Blueberry Revision of XML

Working Draft for Supporting Blueberry Revision of XML Recommendation (1.0) with Particular Emphasis on Ethiopic Script and Writing System November 2001 This Version: http://www.digitaladdis.com/sk/ Ethiopics XML_Proposal_Version1.pdf Latest Ver.: http://www.digitaladdis.com/sk/ Ethiopics XML_Proposal_Version1.pdf Authors/Editors: Samuel Kinde Kassegne (Nanogen, UC San Diego, Engg Ext.) <[email protected]> Bibi Ephraim (Hewlett Packard) <[email protected]> Copyright ©2001, SKK, BE. Working Draft for Supporting Blueberry Revision of XML - Ethiopics Script 1 Abstract This document contains XML example codes, surveys and recommendations that support the need for Ethiopic script-based XML element type and attribute names in Amharic, Afaan Oromo, Tigrigna, Agewgna, Guragina, Hadiya, Harari, Sidama, Kembatigna and other Ethiopian languages that use Ethiopic script. Status of this Document This document is an initial working draft that is to be widely circulated for comment from the Ethiopic XML Interest Group and the wider public. The document is a work in progress. Table of Contents 1. Scope 2. Introduction 3. Objective 4. Review of Status of Native HTML and XML Applications in Ethiopic 4.1. Evolution of Ethiopic Content in HTML 4.2. Ethiopic and XML 5. Hybrid XML Document Markups in Ethiopic 5.1. Examples 5.2. Discussions 6. Fully-Native XML Document Markups in Ethiopic 6.1. Examples 6.2. Discussions 7. Conclusions and Recommendations 8. Appendix 9. References Working Draft for Supporting Blueberry Revision of XML - Ethiopics Script 2 1. Scope The work reported in this document contains XML example codes, surveys and recommendations that support the need for a revision of current XML standards to allow Ethiopic-based XML element type and attribute names in Amharic, Afaan Oromo, Tigrigna, Agewgna, Guragina, Hadiya, Harari, Sidama, Kembatigna and other Ethiopian languages that use Ethiopic script. -

Greek Alphabet ( ) Ελληνικ¿ Γρ¿Μματα

Greek alphabet and pronunciation 9/27/05 12:01 AM Writing systems: abjads | alphabets | syllabic alphabets | syllabaries | complex scripts undeciphered scripts | alternative scripts | your con-scripts | A-Z index Greek alphabet (ελληνικ¿ γρ¿μματα) Origin The Greek alphabet has been in continuous use for the past 2,750 years or so since about 750 BC. It was developed from the Canaanite/Phoenician alphabet and the order and names of the letters are derived from Phoenician. The original Canaanite meanings of the letter names was lost when the alphabet was adapted for Greek. For example, alpha comes for the Canaanite aleph (ox) and beta from beth (house). At first, there were a number of different versions of the alphabet used in various different Greek cities. These local alphabets, known as epichoric, can be divided into three groups: green, blue and red. The blue group developed into the modern Greek alphabet, while the red group developed into the Etruscan alphabet, other alphabets of ancient Italy and eventually the Latin alphabet. By the early 4th century BC, the epichoric alphabets were replaced by the eastern Ionic alphabet. The capital letters of the modern Greek alphabet are almost identical to those of the Ionic alphabet. The minuscule or lower case letters first appeared sometime after 800 AD and developed from the Byzantine minuscule script, which developed from cursive writing. Notable features Originally written horizontal lines either from right to left or alternating from right to left and left to right (boustophedon). Around 500 BC the direction of writing changed to horizontal lines running from left to right. -

Preservation of Original Orthography in the Construction of an Old Irish Corpus

Preservation of Original Orthography in the Construction of an Old Irish Corpus. Adrian Doyle, John P. McCrae, Clodagh Downey National University of Ireland Galway [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Irish was one of the earliest vernacular European languages to have been written using the Latin alphabet. Furthermore, there exists a relatively large corpus of Irish language text dating to this Old Irish period (c. 700 – c 950). Beginning around the turn of the twentieth century, a large amount of study into Old Irish revealed a highly standardised language with a rich morphology, and often creative orthography. While Modern Irish enjoys recognition from the Irish state as the first official language, and from the EU as a full official and working language, Old Irish is almost incomprehensible to most modern speakers, and remains extremely under-resourced. This paper will examine considerations which must be given to aspects of orthography and palaeography before the text of a historical manuscript can be represented in digital format. Based on these considerations the argument will be presented that digitising the text of the Würzburg glosses as it appears in Thesaurus Palaeohibernicus will enable the use of computational analysis to aid in current areas of linguistic research by preserving original orthographical information. The process of compiling the digital corpus, including considerations given to preservation of orthographic information during this process, will then be detailed. Keywords: manuscripts, palaeography, orthography, digitisation, optical character recognition, Python, Unicode, morphology, Old Irish, historical languages glosses]” (2006, p.10). Before any text can be deemed 1. -

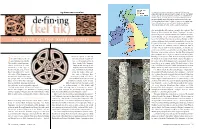

K 03-UP-004 Insular Io02(A)

By Bernard Wailes TOP: Seventh century A.D., peoples of Ireland and Britain, with places and areas that are mentioned in the text. BOTTOM: The Ogham stone now in St. Declan’s Cathedral at Ardmore, County Waterford, Ireland. Ogham, or Ogam, was a form of cipher writing based on the Latin alphabet and preserving the earliest-known form of the Irish language. Most Ogham inscriptions are commemorative (e.g., de•fin•ing X son of Y) and occur on stone pillars (as here) or on boulders. They date probably from the fourth to seventh centuries A.D. who arrived in the fifth century, occupied the southeast. The British (p-Celtic speakers; see “Celtic Languages”) formed a (kel´tik) series of kingdoms down the western side of Britain and over- seas in Brittany. The q-Celtic speaking Irish were established not only in Ireland but also in northwest Britain, a fifth- THE CASE OF THE INSULAR CELTS century settlement that eventually expanded to become the kingdom of Scotland. (The term Scot was used interchange- ably with Irish for centuries, but was eventually used to describe only the Irish in northern Britain.) North and east of the Scots, the Picts occupied the rest of northern Britain. We know from written evidence that the Picts interacted extensively with their neighbors, but we know little of their n decades past, archaeologists several are spoken to this day. language, for they left no texts. After their incorporation into in search of clues to the ori- Moreover, since the seventh cen- the kingdom of Scotland in the ninth century, they appear to i gin of ethnic groups like the tury A.D. -

Ancient and Other Scripts

The Unicode® Standard Version 13.0 – Core Specification To learn about the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see http://www.unicode.org/versions/latest/. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. Unicode and the Unicode Logo are registered trademarks of Unicode, Inc., in the United States and other countries. The authors and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this specification, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. © 2020 Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright, and permission must be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction. For information regarding permissions, inquire at http://www.unicode.org/reporting.html. For information about the Unicode terms of use, please see http://www.unicode.org/copyright.html. The Unicode Standard / the Unicode Consortium; edited by the Unicode Consortium. — Version 13.0. Includes index. ISBN 978-1-936213-26-9 (http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode13.0.0/) 1. -

A Social Network Analysis of Irish Language Use in Social Media

A SOCIAL NETWORK ANALYSIS OF IRISH LANGUAGE USE IN SOCIAL MEDIA JOHN CAULFIELD School of Welsh Cardiff University 2013 This thesis is submitted to the School of Welsh, Cardiff University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD. DECLARATION This work has not been submitted in substance for any other degree or award at this or any other university or place of learning, nor is being submitted concurrently in candidature for any degree or other award. Signed ………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………….. STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD. Signed ………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………….. STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. The views expressed are my own. Signed ………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………….. STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed ………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………….. STATEMENT 4: PREVIOUSLY APPROVED BAR ON ACCESS I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loans after expiry of a bar on access previously approved by the Academic Standards & Quality Committee. Signed ………………………………… (candidate) Date …………………. 2 ABSTRACT A Social Network Analysis of Irish Language Use in Social Media Statistics show that the world wide web is dominated by a few widely spoken languages. However, in quieter corners of the web, clusters of minority language speakers can be found interacting and sharing content. -

Irish in Dublin, the Republic of Ireland's Capital City

The First Official Language? The status of the Irish language in Dublin. Nicola Carty The University of Manchester 1. INTRODUCTION Yu Ming is ainm dom ('my name is Yu Ming') is a short Irish-language film about a Chinese man who, having studied Irish for six months, leaves China and moves to Dublin. On arrival, however, he finds that only one person can understand him. This man explains that despite the bilingual signage visible across the city, Irish is not spoken there. Unable to communicate with the majority of the people he meets, Yu Ming moves to the Gaeltacht1, where he finds employment and settles down. This film makes an important statement about the status of the Irish language. Under Article 8 of the Constitution of Ireland, Irish is the first official language (English is a second official language), and yet, even in the capital city, it is very difficult to use it as a medium of communication. Furthermore, as Irish-language films are not the norm, the very act of producing a film in Irish highlights its position as the marked, atypical language. This paper explores the status of Irish in Dublin, the Republic of Ireland's capital city. I argue that, despite over 100 years of revival attempts, English remains the dominant language and working bilingualism does not exist. Nevertheless, Irish retains an extremely important cultural value that must not be overlooked. I have focused on Dublin because it is the home of the largest concentration of the state's native and L2 Irish speakers2 (Central Statistics Office 2007). -

Pragmatics Or Irish and Irish English

From: Carolina Amador Moreno, Kevin McCafferty and Elaine Vaughan (eds) Pragmatic Markers in Irish English. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 17-36. The Pragmatics of Irish English and Irish Raymond Hickey Abstract The Irish and English languages are spoken by groups of people who belong to the same cultural environment, i.e. both are Irish in the overall cultural sense. This study investigates whether the pragmatics of the Irish language and of Irish English are identical and, if not, to what extent they are different and where these differences lie. There are pragmatic categories in Irish which do not have formal equivalents in English, for instance, the vocative case, the distinction between singular and plural for personal pronouns (though vernacular varieties of Irish English do have this distinction). In addition there are discourse markers in Irish and Irish English which provide material for discussion, e.g. augmentatives and downtoners. Historically, the direction of influence has been from Irish to English but at the present the reverse is the case with many pragmatic particles from English being used in Irish. The data for the discussion stem from collections of Irish and Irish English which offer historical and present-day attestations of both languages. 1. Introduction The aim of the present chapter is to outline the salient pragmatic features of Irish and Irish English. It offers an overview of features from both languages, first English in Ireland (section 2) and then Irish (section 3), proceeding to discuss the possible connections between these features, i.e. considering the likelihood of historical relatedness (section 4).