Legacy, Vol. 20, 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preserving the Automobile: an Auction at the Simeone

PRESERVING THE AUTOMOBILE: AN AUCTION AT THE SIMEONE FOUNDATION AUTOMOTIVE MUSEUM Monday October 5, 2015 The Simeone Foundation Automotive Museum Philadelphia, Pennsylvania PRESERVING THE AUTOMOBILE: AN AUCTION AT THE SIMEONE FOUNDATION AUTOMOTIVE MUSEUM Monday October 5, 2015 Automobilia 11am Motorcars 2pm Simeone Foundation Automotive Museum Philadelphia, Pennsylvania PREVIEW & AUCTION LOCATION INQUIRIES BIDS Simeone Foundation Automotive Eric Minoff +1 (212) 644 9001 Museum +1 (917) 206 1630 +1 (212) 644 9009 fax 6825-31 Norwitch Drive [email protected] Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19153 From October 2-7, to reach us Rupert Banner directly at the Simeone Foundation PREVIEW +1 (917) 340 9652 Automotive Museum: Saturday October 3, 10am to 5pm [email protected] +1 (415) 391 4000 Sunday October 4, 10am to 5pm +1 (415) 391 4040 fax Monday October 5, Motorcars only Evan Ide from 9am to 2pm +1 (917) 340 4657 Automated Results Service [email protected] +1 (800) 223 2854 AUCTION TIMES Monday October 5 Jakob Greisen Online bidding will be available for Automobilia 11am +1 (415) 480 9028 this auction. For further information Motorcars 2pm [email protected] please visit: www.bonhams.com/simeone Mark Osborne +1 (415) 503 3353 SALE NUMBER: 22793 [email protected] Lots 1 - 276 General Information and Please see pages 2 to 7 for Automobilia Inquiries bidder information including Samantha Hamill Conditions of Sale, after-sale +1 (212) 461 6514 collection and shipment. +1 (917) 206 1669 fax [email protected] ILLUSTRATIONS Front cover: Lot 265 Vehicle Documents First session page: Lot 8 Veronica Duque Second session page: Lot 254 +1 (415) 503 3322 Back cover: Lots 257, 273, 281 [email protected] and 260 © 2015, Bonhams & Butterfields Auctioneers Corp.; All rights reserved. -

2010Showfield

2010Showfield Class 01 Brass Pre 1916 1909 Ford Model T 1912 Ford Model T 1910 Oakland 30 24 Runabout Manfred and Nicholas Rein—Mahwah, NJ George C. Bugg—Athens, GA Ron and LeeAnn Laird—Sebring, FL 1910 Cadillac — The Gilmore Museum—Hickory Corners, MI Not Pictured Class 02 Production 1916 - 1948 1929 Pontiac Big Six Cabriolet 1931 Graham Dual Cowl Phaeton 1934 DeSoto Airflow SE Ron and Betsy Thomas—Zanesville, OH Bette Hammond—East Lansing, MI Jay and Peg Crist—York, PA 1935 Ford Type 750 Phaeton (Display) 1937 Cadillac Series 60 Coupe 1937 Lincoln-Zephyr HB-720 Coupe Harvey and Pamela Geiger—Hilton Head, SC Tom Seybert—Jacksonville, FL Cecil Bozarth and Andrea Irby—Chapel Hill, NC 1938 Oldsmobile Series L Convertible 1938 Standard de luxe Flying 10 Paul and Suzanne Etheridge—Montreal, Canada Bob and Linda Pellerin—Virginia Beach, VA 26 2010 HILTON HEAD ISLAND CONCOURS d’ELEGANCE & MOTORING FESTIVAL Class 03A Honored Marque - Chevrolet through 1942 1914 Chevrolet Royal Mail 1918 Chevrolet 490 Light Delivery 1927 Chevrolet Capital Mike Campbell—Savannah, GA Mike Campbell—Savannah, GA Nevy and Kerstin Clark—Savannah, GA 1929 Chevrolet Light Delivery 1930 Chevrolet Club Sedan Landau 1930 Chevrolet Phaeton Mike Campbell —Savannah, GA Bill and Kevin Bennett—Walterboro, SC W. L. “Chip” Boyd—Asheville, NC 1932 Chevrolet Deluxe Sport Roadster 1933 Chevrolet Eagle 1935 Chevrolet Paul and Paula Dimbath—Lakeland, FL Joe and Debbie Lo Cicero—Hardeeville, SC Wayne H. Nation—Griffin, GA 1936 Chevrolet Master Deluxe Town Sedan 1950 Chevrolet Fleetline Mickey Archer—Nicholson, GA Patrick Michael Galletta—Jeffersonton, VA 2010 HILTON HEAD ISLAND CONCOURS d’ELEGANCE & MOTORING FESTIVAL 27 2010Showfield (continued) Class 03B Honored Marque - Chevrolet 1946 - 1972 1955 Chevrolet Cameo - Pickup 1955 Chevrolet Convertible (Display) 1956 Chevrolet Bel Air Wm. -

51871421.Pdf

KATAЛОГ РЕГУЛЯТОРЫ ТОКА BOSCH . 1 DELCO . 14 DENSO . 22 HITACHI . 38 MARELLI . 47 MITSUBISHI . 50 VALEO . 67 ДИОДНЫЕ МОСТЫ 73 BOSCH . 73 DELCO . 81 DENSO . 86 HITACHI . 98 LUCAS . 108 MARELLI . 111 MITSUBISHI . 113 VALEO . 130 2 REGULATOR TERMINAL DESIGNATIONS Battery Ground Indicator Field Computer Electrical System Field Trio Ignition Auxiliary Stator Sense (Earth) Light Report Input Bosch DF B+, S D- D+ 61, L 15 AUX W, STA DFM, FR COM CAV DF D+ D- D+ L STA Chrysler FLD B+ B- L IGN STA Delco F, FLD B+ B-, GRD D+ L I, IGN P, STA F, FR F, FR Delco-Europe DF S D- D+ D+ STA Femsa DF B+ D- D+ L, 61 STA Ford FLD A, AS, B+, S B- L, I, I/L AUX STA GLI, LI PCM, RC Hitachi - ER F B+ E L IGN AUX N Hitachi - IR FLD B+, S E D+ L IGN STA P C, D Iskra DF B+ D- D+ L, 61 STA Lada DF B+, SENSE E L IGN STA Leece-Neville F B+ B- TRIO L IGN STA Lucas DF B+, D+ D- D+ IND IGN STA Magneti Marelli DF, 67 B+, 30 D- D+ IND IGN STA BECM Magneton Pal DF B+ D+ L IGN STA Mando FLD B+ B- D+ L Mitsubishi - ER F B+ E D+ L, N IGN AUX STA Mitsubishi - IR F B+, S E D+ L, N IGN AUX STA FR, P D, FR, G Motorola FLD S, + B- D+ L IGN STA Niehoff FLD S, + B- D+ L IGN STA Nikko FLD B+, S B- D+ L IGN STA Nippondenso - ER F B+ E D+ L IGN AUX STA Nippondenso - IR F B+, S E D+ L IGN AUX STA FR ELD Prestolite FLD B+ B- TRIO L IGN STA Valeo* DF B+, S, + D- D+ L, IND IGN W, STA F PCM *Valeo includes: Ducellier, French Motorola, Paris Rhone, SEV Marchal ABBREVIATION GUIDE - Negative IND Indicator Light Terminal + Positive Int. -

![December 2019 [ $10 ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7446/december-2019-10-837446.webp)

December 2019 [ $10 ]

25/11 DECEMBER 2019 [ $10 ] LOTUS & Clubman Notes THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF LOTUS CLUB VICTORIA AND LOTUS CLUB QUEENSLAND With regular contributions from the WA, SA & NSW branches of Club Lotus Australia FEATURES Sunshine Coast Run Targa High Country 2019 LCQ Christmas Party and LCQ December 2019 Meeting LCV Christmas Party and Concours LCV Concours d’Elegance Winners 2019 LCV Goldfields Weekend Print Post Approved 100001716 MELBOURNE NOW OPEN Mark O’Connor has opened the doors to our new dealership in • New and used sports cars. Melbourne. Many of you already know Mark and his exploits in • Servicing, parts and upgrades. Lotus sports cars including Bathurst 12 hour class wins and more. • Vehicle and body repairs. We are unlike other dealerships, we are staffed by car lovers and • Driving events and motorsport race engineers with unrivalled knowledge and expertise. Mark O’Connor 0418 349 178 379-383 City Road, Southbank [email protected] www.simplysportscars.com SSC Melb - LTS04_Half_page_advert.indd 1 12/4/18 3:59 pm DECEMBER 2019 Lotus & Clubman Notes VOLUME 25 ISSUE 11 by Simon Messenger FEATURES Welcome to the December 2019 edition of Lotus & Clubman Notes. Not only is it the last one of the year, but also my last as your Editor. I hope you have enjoyed reading the magazine over 04 Sunshine Coast Run the last two years and that you have appreciated the improvements that I have made during my 06 DTC at Lakeside tenure. I have received many compliments over that period for which I am very grateful. It has been a very time consuming labour of love. -

We Celebrate One of the Great Racing Car Constructors

LOLA AT 60 WE CELEBRATE ONE OF THE GREAT RACING CAR CONSTRUCTORS Including FROM BROADLEY TO BIRRANE GREATEST CARS LOLA’S SECRET WEAPON THE AUDI CHALLENGER The success of the Mk1 sports-racer, usually powered by the Coventry Climax 1100cc FWA engine, brought Lola Cars into existence. It overshadowed the similar e orts of Lotus boss Colin Chapman and remained competitive for several seasons. We believe it is one of designer Eric Broadleyʼs greatest cars, so turn to page 16 to see what our resident racer made of the original prototype at Donington Park. Although the coupe is arguably more iconic, the open version of the T70 was more successful. Developed in 1965, the Group 7 machine could take a number of di erent V8 engines and was ideal for the inaugural Can-Am contest in ʼ66. Champion John Surtees, Dan Gurney and Mark Donohue won races during the campaign, while Surtees was the only non-McLaren winner in ʼ67. The big Lola remains a force in historic racing. JEP/PETCH COVER IMAGES: JEP/PETCH IMAGES: COVER J BLOXHAM/LAT Contents 4 The story of Lola How Eric Broadley and Martin Birrane Celebrating a led one of racing’s greatest constructors 10 The 10 greatest Lolas racing legend Mk1? T70? B98/10? Which do you think is best? We select our favourites and Lola is one of the great names of motorsport. Eric Broadley’s track test the top three at Donington Park fi rm became one of the leading providers of customer racing cars and scored success in a diverse range of categories. -

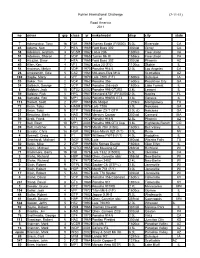

No Driver Grp Class Yr Make/Model Disp City State 7 Adamowicz

Kohler International Challenge (7-11-11) at Road America 2011 no driver grp class yr make/model disp city state 7 Adamowicz, Tony 1b F5A 1969 Gurney Eagle (F/5000) 5.0L Riverside CA 45 Adams, Ken 7 HTA 1969 Ford Boss 302 302cid Gilroy CA 58 Adelman, Graham 3 VCSR 1962 Lotus 23b 1600cc Free Union VA 51 Adelman, Sharon 2 VDP 1965 Turner Mk III 1556cc Free Union PA 43 Alcazar, Drew 7 HTA 1969 Ford Boss 302 302cid Phoenix AZ 49 Alter, Ken 4 VFJ 1962 Lotus 20 (F/J) 1100cc Skokie IL 54 Andrews, Melvin 2 VDP 1970 Porsche 914/4 2.0L Los Angeles CA 26 Arrowsmith, Edie 5 CA2 1964 McLaren-Elva M1A Scottsdale AZ 169 Bagby, Marty 4 VFF 1970 Lola T200 (F/F) 1600cc Dubuque IA 33 Baker, Tim 2 VCP 1962 Porsche 356 1600cc Peachtree City GA 34 Balbach, George 2 VCP 1961 Porsche 356 rdstr 1620cc Lake Forrest IL 6 Baldwin, Jack 10 GTS2 2002 Porsche 996 GT3RS 3.8L Lemont IL 59 Balsley, Rick 5 HFC 1987 Reynard 87SF (FF2000) 2.0L Naples FL 66 Barnaba, Ron 10 MP1 2002 Porsche 996RS GT3 3.6L Geneva IL 113 Barrett, Scott 2 VFP 1969 MG Midget 1275cc Montgomery TX 72 Bean, Toby 5 HASR 1976 Lola T286 3.0L Norcross GA 83 Bean, Toby 9 GTP 1988 Nissan ZX-T GTP 3.0L (t) Norcross GA 21 Beaulieu, Marty 6 HAS 1968 Mercury Cougar 302cid Concord MA 59 Beck, Frank 8 GT1 1972 Porsche 914/6 2.5L Phoenix AZ 77 Bell, Eban 10 MP1 2004 Porsche 996 GT3 Cup 3.6L Highlands Ranch CO 39 Belt, Fletcher 5 HFC 1979 March 79V (F/SV) 1600cc Bull Valley IL 18 Bender, Chris 1a HGP 1982 Ram-March 821 (F/1) 3.0L Reno NV 4 Bennett, Craig 9 F1 1997 Williams FW19 (F/1) 4.0L Hodgkins IL 81 Bernhardt, Michael 9 INDY 1992 Lola 350cid Wichita Falls TX 50 Besic, Mike 2 VDP 1969 Alfa Romeo Duetto 1804cc Glen Ellyn IL 89 Bilicki, Michael 6 HGTO 1965 Ford Mustang GT 289cid Richfield WI 71 Blackmore, Barry 1b F5B 1976 Lola T332 (F/5000) 5.0L Glendale CA 3 Blaha, Richard 6 HBP 1969 Chev. -

Übersicht Rennen WM Endstand Rennfahrer

Übersicht Rennen WM Endstand Rennfahrer Quelle www.f1-datenbank.de Formel 1 Rennjahr 1953 Rennkalender Nr. Datum Land Rennkurs 1 18.01.1953 Argentinien Buenos Aires 2 30.05.1953 USA Indianapolis 500 3 07.06.1953 Niederlande Zandvoort 4 21.06.1953 Belgien Spa Francorchamps 5 05.07.1953 Frankreich Reims 6 18.07.1953 England Silverstone 7 02.08.1953 Deutschland Nürburgring 8 23.08.1953 Schweiz Bremgarten 9 13.09.1953 Italien Monza Punkteverteilung Punktevergabe : Platz 1 = 8 Punkte Platz 2 = 6 Punkte Platz 3 = 4 Punkte Platz 4 = 3 Punkte Platz 5 = 2 Punkte Schnellste Rennrunde = 1 Punkt Gewertet wurden die besten 4 Resultate von 9 Rennen . Renndistanz 300 KM oder mindestens 3 Stunden Besonderheit Fahrerwechsel waren erlaubt. Die erzielten Punkte wurden in diesen Fällen aufgeteilt. Das Rennen von Indianapolis zählte mit zur Weltmeisterschaft, allerdings nahmen die europäischen Teams an dem Rennen nicht teil. Quelle www.f1-datenbank.de Formel 1 Rennjahr 1953 Saisonrennen 1 Datum 18.01.1953 Land Argentinien Rennkurs Buenos Aires Wertung Fahrer Rennteam Motorhersteller Reifenhersteller Sieger Ascari Ferrari Ferrari Pirelli Platz 2 Villoresi Ferrari Ferrari Pirelli Platz 3 González F. Maserati Maserati Pirelli Platz 4 Hawthorn Ferrari Ferrari Pirelli Platz 5 Galvez Maserati Maserati Pirelli Platz 6 Behra Gordini Gordini Englebert Schnellste Rennrunde Ascari Ferrari Ferrari Pirelli Startaufstellung Platz Fahrer Team Motor Zeit KM/H 1 Ascari Ferrari Ferrari 1:49,000 129,204 2 Fangio Maserati Maserati 1:49,100 129,085 3 Villoresi Ferrari Ferrari 1:50,400 127,565 4 Farina Ferrari Ferrari 1:50,400 127,565 5 González F. -

May / June 2017

MAY-JUNEMay 2017-June 2017 THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE THOROUGHBRED ISSN 2207-9327 SPORTS CAR CLUB 1 TOP GEAR May-June 2017 Contents (Fairly) Regular Columns Event Reports ...and About our Club Page 3 Wings Over Illawarra Page 15 Memories of Lammermuir Hills Page 39 Overnight Run to Bowral Page 19 Office of the President Page 4 “Gentleman” Jim Kimberly National Motoring Heritage Day P 23 Page 41 Two-finger Typing Page 7 Formula Ford Experience Page 27 Darren Turner column Page45 2 Coming Events Page 13 Run to Collit’s Inn Page 29 McLaren Movie Preview Page 34 You can’t be serious Page 48 Southern Highlands lunch Page 36 Old and News Page 49 The deadline for copy for the July- Star in an Unreasonably st Priced Car Page 47 August issue of Top Gear will be 21 August. The End Page 54 TOP GEAR May-June 2017 About our Club Calender The Official Calender is published on our web site. Print a Other Information: Current and previous editions may be downloaded here. copy to keep in your historic log booked vehicle. Administration All contributions to: Annual Awards Stephen Knox Club Meetings CAMS M: 0427 705500 Email: Club meetings are held on the 2nd Wednesday of every Club History [email protected] month except December and January at Carlingford Club Plates Bowling Club. Membership Forms Guest Editors Pointscore Alfa Editor: Barry Farr Club Objectives Sporting Aston Martin Editor: Les Johnson • To foster a better acquaintance and social spirit Jaguar Editor: Terry Daly between the various owners of Thoroughbred Sports Disclaimer: Lotus Editor: Roger Morgan Cars in Australia Any opinions published in the Newsletter should not be • To help and advance Thoroughbred Sports Cars in regarded as being the opinion of the Club, of the Other Information: Australia Committee, or of the Editor. -

Lola at Le Mans 2007 Media Guide

Lola at Le Mans 2007 Media Guide B08/60 LMP1 Coupe Preview Test Day Report Lola Team Profiles Complete Lola Le Mans Results A Message from Martin Birrane It goes without saying that Le Mans is the jewel in the crown of global sportscar competition. Indeed, having both raced and entered cars at La Sarthe, it is to my mind the biggest and best motor race in the world. This year, Lola is privileged to have six teams running Huntingdon-built chassis. It is extremely pleasing to see three each of our LMP1 and LMP2 cars here and with such a variety of engines, too. You will find elsewhere in this media guide Lola’s complete results at Le Mans – an invitation to conjure up your own memories from the wonderful past of this uniquely demanding race – and also a peek into the future with the first images of our new LMP1 coupe. I have long believed that Lola’s fortunes are a barometer of the health of sportscar racing and at the moment the market is looking strong, with this weekend’s six Lola entries and the imminent arrival of the first-ever customer LMP1 coupe, the Lola B08/60. As we look ahead to Lola’s 50th anniversary in 2008, the commitment to state-of-the-art technical facilities and outstanding engineering talent will remain the cornerstone of our success and appeal to both manufacturers and privateers seeking sportscar success. I would like to close by personally wishing our customers – and all of our friends throughout the sportscar racing community – the very best of luck in what promises to be an exceptional 75th running of the classic 24 Hours of Le Mans. -

Seasons at a Glance Drivers Starting Position Result Failure And

FIA FORMULA ONE WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP 1950 – 2020 all seasons at a glance drivers cars (Brand+engine+number) starting position result failure and reason © 2021 Erik Schild FIA FORMULA ONE WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP explanation of the abbreviations * Fastest lap (from 1950 to 1959 and from 2019 1 point awarded for this) 0(12) Finished outside the points in position 12 NFt No finish due to technical defect. NFc No finish due to crash, spin. NQ not qualified npq Not prequalified 10 Starting place 0(nc) Finished, but not classified. (too many laps behind) 0(12t) Did not finish because of technical defect, but classified in place 12. NS Qualified, but not started. D Disqualified. WD Retired from the race. (registered) cp Accident in free practice ABC Driven together. Points earned are shared. NFV Fatal accident in race. QV Fatal accident in qualifying. Abbreviations of countries according to ISO 3166 code AR Argentina IN India AT Austria IT Italy AU Australia JP Japan BE Belgium LI Liechtenstein BR Brazil MC Monaco CA Canada MX Mexico CH Switzerland MY Malaysia CL Chile NL Netherlands CO Colombia NZ New Zealand CZ Czechia PL Poland DE Germany PT Portugal DK Denmark RU Russian Federation ES Spain SE Sweden FI Finland TH Thailand FR France US United States of America GB United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland UY Uruguay HU Hungary VE Venezuela ID Indonesia ZA South Africa IE Ireland ZW (RSR) Zimbabwe (Rhodesia) FIA FORMULA ONE WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP 1950 DRIVERS ) 1950 - ) 05 ) - 30 Francorchamps 1950 ( - 1950 ) ) - ) -07- USA 06 ) - - 13 1950 -

Seizoenen in Één Oogopslag

alle seizoenen in één oogopslag Coureurs auto‘s startopstelling uitslag uitval + reden alle gegevens verzameld door Erik Schild ISBN:9789402159073 2e druk 2016 © 2016, Erik Schild digino a" e.co Niets uit deze uitgave ag worden verveelvoudigd, opgeslagen in een geauto atiseerd gegevensbestand en/of openbaar ge aakt door iddel van druk, fotokopie, icrofil of op wat voor wi-ze dan ook, zonder voorafgaande schrifteli-ke toeste ing van de auteur en de uitgever. .his book ay not be reproduced by print, photoprint, icrofil or any other eans, without written per ission fro the translator and the publisher. Puntenverdeling Van 1950 t/m 1960 Van 1960 t/m 1990 Van 1991 t/m 2002 Van 2002-2009 Vanaf 2010 8 1e plaats 9 1e plaats 10 1e plaats 10 1e plaats 25 1e plaats 6 2e plaats 6 2e plaats 6 2e plaats 8 2e plaats 18 2e plaats 4 3e plaats 4 3e plaats 4 3e plaats 6 3e plaats 15 3e plaats 3 4e plaats 3 4e plaats 3 4e plaats 5 4e plaats 12 4e plaats 2 5e plaats 2 5e plaats 2 5e plaats 4 5e plaats 10 5e plaats 1 6e plaats 1 6e plaats 3 6e plaats 8 6e plaats 2 7e plaats 6 7e plaats 1 8e plaats 4 8e plaats 2 9e plaats 1 10e plaats * Snelste ronde (vanaf 1950 t/m 1959 hiervoor 1 punt toe ekend) 0(12) Gefinisht buiten de punten op plaats 12 NFt Geen finish vanwe e technisch mankement. NFc Geen finish vanwe e crash, spin. NQ Niet ekwalificeerd np, Niet voor ekwalificeerd 10 Startplaats 0(nc) -el efinisht, maar niet eklassificeerd. -

Antique & Classic 1959

Antique & Classic v TIMESv April 2019 A publication of the Montana Pioneer and Classic Auto Club 1959 - 2019 ANTIQUE & CLASSIC TIMES CHAPTER MEETINGS Official publication of the Montana Pioneer and Classic Bitterroot Valley Dusters: Regular meeting third Sunday Auto Club, Inc. afternoon of each month at places previously decided upon in Hamilton area. Published quarterly: January, April, July and October. Bozeman Antique Auto Club: Regular meeting second The “Times” is exchanged with other like clubs in the US Friday of each month at random locations in Bozeman. and Canada. Capital Carriages: Regular meeting second Sunday MP&CAC OFFICERS of each month, 2:00 p.m. random locations in Helena. President: Dan Costle 1610 Gates Dr. Central Montana Trail Dusters: Regular meeting fourth Opportunity, MT 59711 Thursday of each month at places previously decided upon in Central Montana area. Vice President: Fritz Seitz 500 5th St So Flathead Pioneer Auto Club: Regular meeting first Great Falls, MT 59405 Sunday of each month at Flathead Electric Co-op in Kalispell. Secretary: Sie Schindler 401 7th Ave So #209 Goggles & Dusters: Regular meeting first Tuesday of Lewistown, MT 59457 each month at Elk’s Lodge, 934 Lewis Ave at 6:00 p.m. (unless otherwise notified) in Billings. Treasurer: Mary Seelmeyer 1210 Ave B NW Great Falls Skunkwagon: Regular meeting first Friday Great Falls, MT 59405 of each month, 7:00 p.m. Eagle’s Lodge 1509 9th St So in Great Falls. Fashion Consultant: Kathy Meuchel 577 Sky Way Drive Hi-Line Antique Auto Club: Regular meeting third Hamiltion, MT 59840 Sunday of each month, 7:00 p.m.