Strategic Planning for City Attractiveness in Sicily

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guida Alla Città E Ai Suoi Quartieri Scritta E Illustrata Dai Ragazzi

Guida alla città e ai suoi quartieri scritta e illustrata dai ragazzi Comune di Catania Assessorato alle Politiche Scolastiche Comune di Catania Assessorato alle Politiche Scolastiche X Direzione - Servizio Istruzione Ufficio Attività Parascolastiche Guida alla città e ai suoi quartieri scritta e illustrata dai ragazzi A cura di Enrico Iachello e Antonino Indelicato Contributo L. 285/97 Assessorato Servizi Sociali pag. 4 La città immaginata Umberto Scapagnini, Giuseppe Maimone pag. 6 Introduzione Enrico Iachello, Antonino Indelicato Parte prima pag. 10 La storia pag. 18 Le vicende urbanistiche pag. 22 L’architettura pag. 36 I luoghi caratteristici pag. 46 I musei pag. 50 Il viale dei catanesi illustri pag. 54 La festa di s. Agata pag. 58 Le tradizioni Parte seconda pag. 66 Centro storico pag. 80 Ognina - Picanello pag. 90 Borgo - Sanzio pag. 98 Barriera - Canalicchio pag. 102 S. Giovanni Galermo pag. 108 Trappeto nord - Cibali pag. 116 Monte Po - Nesima pag. 120 S. Leone - Rapisardi pag. 128 S. Giorgio - Librino pag. 134 S. Giuseppe la Rena - Zia Lisa ©2007 pag. 136 Bibliografia Comune di Catania Assessorato alle Politiche Scolastiche pag. 137 Elenco delle scuole partecipanti Governare oggi una città è compito non facile. Una sfida continua. Senza soste. Un confronto permanente con il resto del mondo che si propone e appare ai nostri occhi con nuove infinite varianti. A volte accettabili, a volte incredibili. Eppure reali, concrete. Davanti a noi. Come macigni. Sembra quasi che vengano da un altro pianeta. E invece, no. I portatori del cambiamento sono individui, esseri umani come noi. Siamo tutti protagonisti del cambiamento. Che, a guardar bene, c'è sempre stato nella storia della vita. -

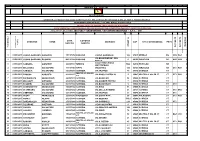

Posti Disponibili Per Contratti a Tempo Determinato - Personale Ata

POSTI DISPONIBILI PER CONTRATTI A TEMPO DETERMINATO - PERSONALE ATA ASSISTENTI AMMINISTRATIVI POSTI ORARI IN POSTI IN N. COMUNE ISTITUZIONE SCOLASTICA POSTI AL 31/08 POSTI AL 30/06 OF ADEGUAMENTO 1 ACIREALE I.C. G. GALILEI 1 2 ACIREALE I.I.S.S GALILEI-FERRARIS h. 6 3 ACIREALE IST. MAG. "R. ELENA" 1 4 ACI SANT'ANTONIO I.C. F. DE ANDRE' 1 5 ADRANO I.C. GUZZARDI 1 6 ADRANO LICEO G. VERGA 1 7 ADRANO III C.D. POLITI 1 8 ADRANO S.M.S. MAZZINI 1 9 ADRANO I.T.S. P. BRANCHINA 1 10 BELPASSO I.C. GIOVANNI PAOLO II 2 11 BELPASSO S.M.S. MARTOGLIO 1 12 BIANCAVILLA II C.D. BIANCAVILLA 1 13 BRONTE I.I.S.S. B. RADICE 1 14 BRONTE I.I.S.S. CAPIZZI 1 15 CALATABIANO I.C. MACHERIONE 1 16 CALTAGIORNE I.C. NARBONE 1 h. 12 17 CALTAGIRONE LICEO SECUSIO h. 6 h. 18 18 CALTAGIRONE C.T.P. N. 8 (NARBONE) 1 19 CATANIA IISS VACCARINI 20 CATANIA I.C BATTISTI 2 h. 6 21 CATANIA CONVITTO CUTELLI 1 22 CATANIA I.C. TEMPESTA 1 23 CATANIA I.C DUSMET-DORIA 1 24 CATANIA I.C. GIUFFRIDA h. 18 25 CATANIA I.C. SAN GIORGIO 1 26 CATANIA I.C. FONTANAROSSA 1 27 CATANIA I.C. PARINI 1 28 CATANIA I.T.I. ARCHIMEDE 1 29 CATANIA I.I.S.S. DUCA ABRUZZI h. 24 (18+6) 30 CATANIA I.I.S.S DE FELICE-OLIVETTI h. 18 31 CATANIA S.M.S. Q. -

Valori Agricoli Medi Della Provincia Annualità 2018

Ufficio del territorio di CATANIA Data: 14/02/2019 Ora: 12.04.17 Valori Agricoli Medi della provincia Annualità 2018 Dati Pronunciamento Commissione Provinciale Pubblicazione sul BUR n.381 del 31/01/2018 n.- del - REGIONE AGRARIA N°: 1 REGIONE AGRARIA N°: 2 VERSANTE OCCIDENTALE ETNA VERSANTE LITORANEO ETNA Comuni di: ADRANO, BIANCAVILLA, BRONTE, MALETTO, Comuni di: CASTIGLIONE DI SICILIA, LINGUAGLOSSA, MILO, RANDAZZO, MANIACE NICOLOSI, PIEDIMONTE ETNEO, SANT`ALFIO, ZAFFERANA ETNEA COLTURA Valore Sup. > Coltura più Informazioni aggiuntive Valore Sup. > Coltura più Informazioni aggiuntive Agricolo 5% redditizia Agricolo 5% redditizia (Euro/Ha) (Euro/Ha) AGRUMETO 23240,56 21691,19 BOSCO CEDUO 2169,12 2427,35 BOSCO D`ALTO FUSTO 3047,10 3615,20 BOSCO MISTO 1807,60 CANNETO 3615,20 3356,97 CHIUSA 12963,07 FICODINDIETO 4372,32 FICODINDIETO IRRIGUO 13032,78 FRUTTETO 32226,91 26318,65 FRUTTETO IRRIGUO 36523,83 30078,45 INCOLTO PRODUTTIVO 1497,73 1497,73 MANDORLETO 6795,53 NOCCIOLETO 8955,36 12246,23 SI SI ORTO IRRIGUO 37651,78 22930,48 PASCOLO 1988,36 1988,36 Pagina: 1 di 8 Ufficio del territorio di CATANIA Data: 14/02/2019 Ora: 12.04.17 Valori Agricoli Medi della provincia Annualità 2018 Dati Pronunciamento Commissione Provinciale Pubblicazione sul BUR n.381 del 31/01/2018 n.- del - REGIONE AGRARIA N°: 1 REGIONE AGRARIA N°: 2 VERSANTE OCCIDENTALE ETNA VERSANTE LITORANEO ETNA Comuni di: ADRANO, BIANCAVILLA, BRONTE, MALETTO, Comuni di: CASTIGLIONE DI SICILIA, LINGUAGLOSSA, MILO, RANDAZZO, MANIACE NICOLOSI, PIEDIMONTE ETNEO, SANT`ALFIO, ZAFFERANA -

Presidio Veterinario Aziendale Per Anagrafe Canina

REGIONE SICILIANA AZIENDA SANITARIA PROVINCIALE CATANIA Presidio Veterinario Aziendale per anagrafe Canina Distretto Sanitario di Sanità Pubblica Per i Comuni di: Numero Telefonico Veterinaria Giorno Feriale di Prenotazione Sede Ricevimento ed Orario Giorni Feriali dal Lunedì al Venerdì Tutti i Giovedì Aci Bonaccorsi, Aci Castello, Aci Catena, dalle 09,00 alle 12,00 Via Antillo n. 3 ACIREALE Aci S. Antonio, Acireale, S. Venerina, 2° Lunedì di ogni mese dalle 095/801809 Acireale Zafferana. 16,00 alle 18,00 Dalle 09,00 alle 12,00 (su prenotazione) Adrano, Biancavilla, S.M. di Licodia, ADRANO/PATERNO' SU PRENOTAZIONE 095/7975082-5086 Belpasso, Paternò, Ragalna. Dalle 09,00 alle 12,00 C.da Cantera (ex macello) BRONTE SU PRENOTAZIONE Bronte Bronte, Maletto, Maniace, Randazzo. 095/7746708 2° e 4° martedì di ogni mese P.zza San Vincenzo Dalle 09,00 alle 12,00 BRONTE dalle 15,00 alle 18,00 Randazzo (su prenotazione) REGIONE SICILIANA AZIENDA SANITARIA PROVINCIALE CATANIA REGIONE SICILIANA AZIENDA SANITARIA PROVINCIALE CATANIA Presidio Veterinario Aziendale per anagrafe Canina Distretto Sanitario di Sanità Pubblica Per i Comuni di: Numero Telefonico Veterinaria Giorno Feriale di Prenotazione Sede Ricevimento ed Orario Giorni Feriali dal Lunedì al Venerdì Lunedì e Giovedì dalle 09,00 alle 12,00 095/482135 Via Padre A. Secchi n. 10, CATANIA Catania, Motta, Misterbianco, Giovedì pomeriggio 095/2545381 Catania (su prenotazione) Dalle 09,00 alle 12,00 dalle 16,00 alle 18,00 Caltagirone, Mazzarrone, Mineo, San c.da Molona 1° e 3° Giovedì di ogni mese CALTAGIRONE 800 - 011541 Michele di Ganz. Caltagirone 15,30 - 19,30 Via Cavour (ex macello) 3° mercoledì di ogni mese CALTAGIRONE Grammichele, Licodia Eubea, Mazzarrone 0933/859300 Grammichele 15,30 - 19,00 Via Vecchia Ferrovia s.n. -

UST 18 Siracusa ATC SR1 Graduatoria Definitiva Cacciator.Pdf

REPUBBLICA ITALIANA Regione Siciliana ASSESSORATO REGIONALE DELL'AGRICOLTURA, DELLO SVILUPPO RURALE E DELLA PESCA MEDITERRANEA DIPARTIMENTO REGIONALE DELLO SVILUPPO RURALE E TERRITORIALE SERVIZIO 18 UFFICIO SERVIZIO PER IL TERRITORIO DI SIRACUSA UNITA' OPERATIVA n°3 GESTIONE DELLE RISORSE NATURALISTICHE- RIPARTIZIONE FAUNISTICO VENATORIA DI SIRACUSA STAGIONE VENATORIA 2016/2017 - GRADUATORIA CACCIATORI REGIONALI - A.T.C.: SR1 RACCOMANDATA POSIZIONE ALTRI ATC ALTRI ATC PRIORITA' N. CIVICO DATA DATA LUOGO DI COGNOME NOME INDIRIZZO CAP CITTA' DI RESIDENZA PROV NASCITA NASCITA 1 01/01/2015 CUGNO GARRANO GIUSEPPE 15/11/1950 PACHINO CORSO GARIBALBI 106 97015 MODICA RG SR2 RG1 1 VIA BENEVENTANO DEL 2 01/01/2015 CUGNO GARRANO ROSARIO 08/12/1944 PACHINO 6 96100 SIRACUSA SR RG1 RG2 2 BOSCO C/DA FINOCCHIARA 3 01/01/2015 CANNATA GIUSEPPE 20/03/1977 MODICA SNC 96019 ROSOLINI SR 2 GROTTICELLE 4 01/01/2015 BELLAVITA SALVATORE 11/11/1980 NOTO VIALE TICA 149 96100 SIRACUSA SR CT2 RG1 2 5 01/01/2015 CANIGLIA SALVATORE 19/09/1933 SCORDIA VIA TRAPANI 75 95048 SCORDIA CT 3 MILITELLO VAL DI 6 01/01/2015 RAGUSA AUGUSTO 21/10/1937 VIA MASS. D'AZEGLIO 5 95043 MILITELLO VAL DI CT CT CT2 RG1 3 CT 7 01/01/2015 ZAPPARRATA SEBASTIANO 28/05/1939 SCORDIA VIA BRANCATI 14 95048 SCORDIA CT 3 8 01/01/2015 MILLUZZO GIOVANNI 24/06/1939 SCORDIA VIA SANDRO PERTINI 7 95048 SCORDIA CT 3 9 01/01/2015 SCUDERI SALVATORE 04/01/1940 SCORDIA VIA BASCHELET 5 95048 SCORDIA CT CT2 3 10 01/01/2015 DI BENEDETTO SEBASTIANO 15/04/1942 SCORDIA VIA ETNA 13 95048 SCORDIA CT 3 11 01/01/2015 DI -

Cartina-Guida-Stradario-Catania.Pdf

ITINERARI DI CATANIA CITTÀ D’ARTE ITINERARI ome scoprire a fondo le innumerevoli bellezze architettoniche, Cstoriche, culturali e naturalistiche di Catania? Basta prendere par- te agliItinerari di Catania Città d’Arte , nove escursioni offerte gra- tuitamente dall’Azienda Provinciale Turismo, svolte con l’assistenza ittà d’arte di esperte guide turistiche multilingue. Come in una macchina del tempo attraverserete secoli di storia, dalle origini greche e romane fino ai giorni nostri, passando per la rinasci- ta barocca del XVII secolo e non dimenticando Vincenzo Bellini, forse il più illustre dei suoi figli, autore di immortali melodie che hanno reso OMAGGIO! - FREE! la nostra città grande nel mondo. Catania, dichiarataPatrimonio dell’Umanità dall’Unesco per il suo Barocco, è stata distrutta dalla lava sette volte e altrettante volte riedifica- ta grazie all’incrollabile volontà dei suoi abitanti, gente animata da una grande devozione per Sant’Agata, patrona della città, cui sono dedicate tante chiese ed opere d’arte, nonché una delle più belle feste religiose AZIENDA PROVINCIALE TURISMO che si possa ammirare. PROVINCIAL TOURISM BOARD Con l’escursione al Museo di Zoologia, all’Orto Botanico e all’Erbario via Cimarosa, 10 - 95124 Catania del Mediterraneo scoprirete le peculiarità naturalistiche del territorio tel. 095 7306211 - fax: 095 316407 etneo e non solo, mentre grazie all’itinerario “Luci sul Barocco” potrete www.apt.catania.it - [email protected] effettuare una piacevole passeggiata notturna per le animate strade della movida catanese, attraversando piazze e monumenti messi in risalto da ammalianti giochi di luce. Da non perdere infine l’itinerario “Letteratura e Cinema”, un affascinan- te viaggio tra le bellezze architettoniche e le indimenticabili atmosfere protagoniste indiscusse di tanti romanzi e film di successo. -

Palermo Guide

how to print and assembling assembleguide the the guide f Starting with the printer set-up: Fold the sheet exactly in the select A4 format centre, along an imaginary line, and change keeping the printed side to the the direction of the paper f outside, from vertical to horizontal. repeat this operation for all pages. We can start to Now you will have a mountain of print your guide, ☺ flapping sheets in front of you, in the new and fast pdf format do not worry, we are almost PDF there, the only thing left to do, is to re-bind the whole guide by the edges of the longest sides of the sheets, with a normal Now you will have stapler (1) or, for a more printed the whole document aesthetic result, referring the work to a bookbinder asking for spiral binding(2). Congratulations, you are now Suggestions “EXPERT PUBLISHERS”. When folding the sheet, we would suggest placing pressure with your fingers on the side to be folded, so that it might open up, but if you want to permanently remedy this problem, 1 2 it is enough to apply a very small amount of glue. THE PALERMO CITY GUIDE © Netplan - Internet solutions for tourism © Netplan - Internet solutions for tourism © 2005 Netplan srl. All rights reserved. © Netplan - Internet solutions for tourism All material on this document is © Netplan. THE PALERMO CITY GUIDE 1 Summary THINGS TO KNOW 3 History and culture THINGS TO SEE 4 Churches and Museums 6 Historical buildings and monuments 8 Places and charm THINGS TO TRY 10 Food and drink 11 Shopping 12 Hotels and lodgings THINGS TO EXPERIENCE 13 Events 14 La Dolce Vita ITINERARIES 15 A special day 16 Trip outside the city 32 © Netplan - Internet solutions for tourism THE PALERMO CITY GUIDE / THINGS TO KNOW 3 4 THE PALERMO CITY GUIDE / THINGS TO SEE History and culture Churches and Museums population spread out throughout the island. -

LETIZIA BATTAGLIA.Just for Passion

LETIZIA BATTAGLIA .Just for passion MAXXI is dedicating an anthological exhibition to the great Sicilian artist with over 250 photographs testifying to 40 years of Italian life and society 24 November 2016 – 17 April 2017 #LetiziaBattaglia | #PerPuraPassione www.fondazionemaxxi.it Born in Palermo in 1935 and known throughout the world for her photos of the mafia, Letizia Battaglia has provided and continues to provide one of the most extraordinary and acute visual testimonies to Italian life and society, in particular that of Sicily.Recognised as one of the most important figures in contemporary photography for the civic and ethical value of her work, Letizia Battaglia is not only the “photographer of the mafia” but also, through her artistic work and as a photo reporter for the daily newspaper L’Ora , the first woman and in 1985 in New York she became the first European photographer to receive the prestigious international W. Eugene Smith Award , the international prize commemorating the Life photographer . Shortly after the celebrations for her 80 th birthday, MAXXI is organizing LETIZIA BATTAGLIA.Just for passion , a major exhibition curated by Paolo Falcone, Margherita Guccione and Bartolomeo Pietromarchi , that from 24 November 2016 through to 17 April 2017 brings to MAXXI over 250 photographs, contact sheets and previously unseen vintage prints from the archive of this great artist, along with magazines, publications, films and interviews. Visual testimony to the bloodiest mafia atrocities and and social and political reality of Italy, a number of her shots are firmly embedded in the collective consiousness: Giovanni Falcone at the funeral of the General Dalla Chiesa ; Piersanti Mattarella asassinated in the arms of his brother Sergio; the widow of Vito Schifano ; the boss Leoluca Bagarella following his arrest; Giulio Andreotti with Nino Salvo . -

Innovative Tools of Smart Agriculture to Protect the Supply Chain of Sicilian Blood Orange Pgi

Procedia Environmental Science, Engineering and Management http://www.procedia-esem.eu Procedia Environmental Science, Engineering and Management 7 (2020) (2) 175-184 24th International Trade Fair of Material & Energy Recovery and Sustainable Development, ECOMONDO, 3th-6th November, 2020, Rimini, Italy INNOVATIVE TOOLS OF SMART AGRICULTURE TO PROTECT THE SUPPLY CHAIN OF SICILIAN BLOOD ORANGE PGI Eleonora Roberta Villari1, Federico Mertoli1, Giuseppe Tripi2, Agata Matarazzo1, Elena Albertini3 1Department of Economy and Business, University of Catania, 55 C.so Italia, 95129 Catania, Italy 2Department of Agriculture & Forestry, University of Catania, 100 Santa Sofia, 95123 Catania, Italy 3Consorzio di Tutela Arancia Rossa di Sicilia, S.G. La Rena, 30b, 95100 Catania, Italy Abstract Nowadays, with regard to the final purchase of agri-food products, consumers are very careful to every feature of a foodstuff, such as its “organoleptic” quality or its respect for the environment, which leads to a major consumption of local products and the development of what is called a “Km0 dietary” to reduce CO2 emissions in the atmosphere and food waste. In order to safeguard the environment and to protect both food excellences and consumers from counterfeiting, voluntary standards and innovative tools can be used: EU quality labels, voluntary standards such as the UNI EN ISO 22005:2007, and innovative tools of agriculture 4.0, i.e. blockchain technology. The aim of the paper is to test the interest in purchasing the Sicilian Blood Orange PGI in the French market, inasmuch considered particularly attractive for citrus fruits. In order to achieve this purpose qualitative and quantitative analysis are conducted to verify if it is convenient, for the Consortium of Protection, to implement protection tools to the orange juice made up of 100% Blood Oranges of Sicily PGI. -

DISTRETTO DI ACIREALE • Acireale • Aci Bonaccorsi • Aci Castello • Aci Catena • Aci S. Antonio • Santa Venerina •

DISTRETTO DI ACIREALE • Acireale • Aci Bonaccorsi • Aci Castello • Aci Catena • Aci S. Antonio • Santa Venerina • Zafferana Etnea 4 1 DISTRETTO DI ACIREALE Questi servizi non sono presenti in tutti i comuni. Sono collocati solo in alcuni dei comuni del distretto sanitario. Sono però utilizzabili da tutti i cittadini che ne hanno bisogno. Nel caso in cui un servizio o una prestazione non siano presenti in questo distretto, consultate il punto salute - URP del vostro distretto. Punto Salute URP 095/7677824 Via Martinez n. 19 Acireale Da Lunedì a Venerdì 8:00-13:00 • Martedì 15:30-18:00 SERVIZI SEDE ACCESSO DIREZIONE SANITARIA Via Martinez, 19 DISTRETTO Tel. 095/7677802 EDUCAZIONE ALLA SALUTE: Via Martinez, 19 Lun e Mart. previo appuntamento Coordina iniziative e progetti di Tel. 095/7677860 Mer. e Ven. 9,00 - 12,00 educazione alla salute. REGISTRO TRAPIANTI: Via Felice Paradiso, 7 Lun. Merc. Ven. 9,30 - 12,30 punto di accettazione delle Tel. 095/7677861 dichiarazioni di volontà dei cittadini Tel. 095/7677824 alla donazione di organi . IMMIGRATI Via Martinez,19 Mart. a Ven. 8,30 - 12,00 (senza permesso di soggiorno) Tel. 095/894492 Rilascio tessera sanitaria provvisoria. Codice STP Mart. 15,30 - 17,00 INVALIDI CIVILI Via Martinez,19 Mart. e Ven. 11,00-13,00 Presentazione domande e visite Tel. 095/7677812 mediche Tel. 095/7677813 TICKET Via Paolo Vasta, 189 Da Lun. a Ven. 8,30 - 12,00 Riscossione specialistiche Mart. e Giov. 15,30 - 17,30 ASSISTENZA INDIRETTA: Via Martinez, 19 Da Lun. a Ven. 8,30 - 12,00 rimborsi: Tel. -

Reports and Financials As at 31 December 2015

Financials Rai 2015 Reports and financials 2015 December 31 at as Financials Rai 2015 Reports and financials as at 31 December 2015 2015. A year with Rai. with A year 2015. Reports and financials as at 31 December 2015 Table of Contents Introduction 5 Rai Separate Financial Statements as at 31 December 2015 13 Consolidated Financial Statements as at 31 December 2015 207 Corporate Directory 314 Rai Financial Consolidated Financial Introduction Statements Statements 5 Introduction Corporate Bodies 6 Organisational Structure 7 Letter to Shareholders from the Chairman of the Board of Directors 8 Rai Financial Consolidated Financial Introduction 6 Statements Statements Corporate Bodies Board of Directors until 4 August 2015 from 5 August 2015 Chairman Anna Maria Tarantola Monica Maggioni Directors Gherardo Colombo Rita Borioni Rodolfo de Laurentiis Arturo Diaconale Antonio Pilati Marco Fortis Marco Pinto Carlo Freccero Guglielmo Rositani Guelfo Guelfi Benedetta Tobagi Giancarlo Mazzuca Antonio Verro Paolo Messa Franco Siddi Secretary Nicola Claudio Board of Statutory Auditors Chairman Carlo Cesare Gatto Statutory Auditors Domenico Mastroianni Maria Giovanna Basile Alternate Statutory Pietro Floriddia Auditors Marina Protopapa General Manager until 5 August 2015 from 6 August 2015 Luigi Gubitosi Antonio Campo Dall’Orto Independent Auditor PricewaterhouseCoopers Rai Financial Consolidated Financial Introduction Statements Statements 7 Organisational Structure (chart) Board of Directors Chairman of the Board of Directors Internal Supervisory -

Lerivoluzionidel 1837E Del1848-1849

LLeeRRiivvoolluuzziioonnii ddeell 11883377 ee ddeell 11884488--11884499 Nella prima metà dell’Ottocento, Catania fu protagonista in ciascuna delle sollevazioni contro il giovane Regno delle Due Sicilie, nato nel 1816 e sempre, forse oltre i suoi veri demeriti, inviso ai siciliani Al suo primo sovrano Ferdinando, si imputava, infatti, di aver abolito la Costituzione “inglese” del 1812 e quella spagnola del 1820. A smorzare la loro tenace animosità non valse certo l’opera del successore Ferdinando II, incoronato nel 1830 che accentrò a Napoli il goveerno del regno in spregio alle secolari autonomie garantite in passato all’ isola . Per conseguenza, al giungere del colera, proveniente dal continente, nell’estate del 1837 era radicato in ogni strato della popolazione il convincimento che si volesse stroncare la latente ribellione della Sicilia con una micidiale pestilenza. L’aggravarsi dell’epidemia a Catania costrinse il 15 giugno la Giunta Sanitaria Provinciale, convocata dall’Intendente principe Alvaro Paternò di Manganelli, a disporre la chiusura preventiva dei pozzi di Battiati ed il Pozzo Molino. L’ignoranza ed il pregiudizio fecero ravvisare proprio in questa misura di profilassi una conferma alla diceria di una volontaria contaminazione delle fonti d’acqua. Condussero il malcontento popolare - espresso dal verso “veni lu mali veni ccu malizia Diu ppi Manu di l’omu fa giustizia” – ad esiti rivoluzionari taluni borghesi esponenti delle professioni come Salvatore Barbagallo Pittà, trentaseienne fondatore del giornale letterario “Lo Stesicoro”, Gaetano Mazzaglia, Giuseppe Caudullo Guarrera, Giacinto Gulli Pannetti, Giovanbattista Pensabene, Giuseppe Caudullo Amore, Angelo Sgroi, Sebastiano Sciuto, Al movimento aderirono alcuni rappresentanti dell’aristocrazia come l’influente marchese Antonino Paternò Castello di San Giuliano, cui venne affidata la guida della neocostituita Giunta di Pubblica Sicurezza.