Mobile Payment Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Service Provider Name Region AOC Date Assessor DESV

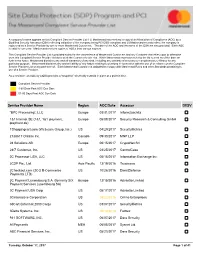

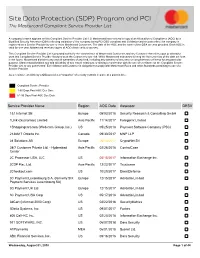

A company’s name appears on this Compliant Service Provider List if (i) Mastercard has received a copy of an Attestation of Compliance (AOC) by a Qualified Security Assessor (QSA) reflecting validation of the company being PCI DSS compliant and (ii) Mastercard records reflect the company is registered as a Service Provider by one or more Mastercard Customers. The date of the AOC and the name of the QSA are also provided. Each AOC is valid for one year. Mastercard receives copies of AOCs from various sources. This Compliant Service Provider List is provided solely for the convenience of Mastercard Customers and any Customer that relies upon or otherwise uses this Compliant Service Provider list does so at the Customer’s sole risk. While Mastercard endeavors to keep the list current as of the date set forth in the footer, Mastercard disclaims any and all warranties of any kind, including any warranty of accuracy or completeness or fitness for any particular purpose. Mastercard disclaims any and all liability of any nature relating to or arising in connection with the use of or reliance on the Compliant Service Provider List or any part thereof. Each Mastercard Customer is obligated to comply with Mastercard Rules and other Standards pertaining to use of a Service Provider. As a reminder, an AOC by a QSA provides a “snapshot” of security controls in place at a point in time. Compliant Service Provider 1-60 Days Past AOC Due Date 61-90 Days Past AOC Due Date Service Provider Name Region AOC Date Assessor DESV “BPC Processing”, LLC Europe 03/31/2017 Informzaschita 1&1 Internet SE (1&1, 1&1 ipayment, Europe 05/08/2017 Security Research & Consulting GmbH ipayment.de) 1Shoppingcart.com (Web.com Group, lnc.) US 04/29/2017 SecurityMetrics 2138617 Ontario Inc. -

October 2015 Cover Story

OCTOBER 2015 COVER STORY Six different letters of the alphabet are turning the mPOS segment on its head these days: EMV and NFC. iZettle announced in late June that it would be the first to NFC enable its mPOS reader which was EMV-enabled from the start. As a technology company headquartered in Sweden, for its mPOS solution to work, that was a critical requirement, but its announcement in July was intended to signal its compatibility with Apple Pay, which launched in July in the U.K. Then, later that summer, Square announced that it would NFC enable dongles for micro- merchants to use. EMV was something it had incorporated into its readers earlier in the year and its newfound embrace of NFC was intended to also ride the “Pay” bandwagons in the U.S. – Apple and Android. Square also said that it planned to give away 250k of them to give micro- merchants the same acceptance leg up that larger retailers have in accepting not only chip payments but mobile-enabled EMV payments. And just this week, PayPal threw its mPOS hat into the EMV/NFC ring. PayPal Here, which, today, is compatible with iOS and Android devices, now accepts chip cards (both EMV chip-and-PIN and EMV chip-and-signature), magnetic stripe and NFC transactions, including Apple Pay, Android Pay and Samsung Pay, along with other NFC-enabled devices and cards. All of this is part of PayPal’s plan to integrate payments within a more tailored solution for retailers. A recent study shows that mPOS will juxtapose the proliferation of mobile services in retail — for pushing offers, tracking inventory and sales. -

A Comparison Study of Digital Business Models Between China and Switzerland

A comparison study of digital business models between China and Switzerland The key factors of the digital business models with focus on the retail industry Bachelor Thesis Bachelor of Science in Business Information Technology Proposed by Shengya Lin Matr.-Nr.: 16561235 27. May 2020 Zurich University of Applied Sciences School of Management and Law Supervisor: Dr.-Ing. Martin Schnauss Management Summary Management Summary Digitisation involves changes in different areas of society and defines the new direction of businesses. The most visible field of which is the retail industry. Moreover, technology-oriented business models become a modern and pref- erable way among consumers. Notably, China’s high GDP growth is highly related to this development because digital retail already penetrated daily life and formed a business eco-system. In contrast, the effect of those business models has not yet overtaken the Swiss economy, since the traditional market is still dominant regarding its profound economy structure. However, new emerging technologies may have the chance to lead another revolution and hence bring the large potential of digital business opportunity globally. This Bachelor thesis aims to compare the business environment of digital busi- ness models in the retail industry between China and Switzerland. It discusses different macroenvironment perspectives to scrutinise the key factors. This thesis approaches the research question with the qualitative method. The empirical part consists of a comprehensive literature review and interviews with experienced cross-country experts in China and Switzerland. Further- more, the professional literature of both countries primarily contributes to the development of the theoretical background. In addition, interviews with Mr. -

The Mastercard SDP Program (Site Data Protection)

The MasterCard SDP Program (Site Data Protection) Compliant Service Providers Company Name AOC Date Assessor 1&1 Internet AG 5/2/2012 Security Research & Consulting 1Link (Guarantee) Limited 11/18/2011 Trustwave 1ShoppingCart.com 6/29/2011 SecurityMetrics 1stPayGateway 5/28/2012 IBM Internet Security Systems (IS 2000 Charge, Inc. 11/11/2011 Tevora Business Solutions 24 Solutions AB 5/13/2011 NTT Security Ltd. 3 Delta Systems, Inc. 10/5/2011 Fortrex 3dCart (Informat 2000 Corp) 2/14/2012 SecurityMetrics 888extramoney.com (Extrameasures) 6/22/2012 Coalfire Systems, Inc. A3 IT Services (A3ITS) 12/27/2011 Trustwave A6IT Ltd. 5/14/2012 Kyte Consultants, Ltd. ABC Financial Services, Inc. 5/17/2012 Trustwave Abtran Ltd. 9/1/2011 Rits Acadaca, LLC 3/22/2012 Fortrex Monday, July 02, 2012 Page 1 of 64 Company Name AOC Date Assessor Accel Networks 12/27/2011 Trustwave Accelya Madrid - Vivaldi Product 1/10/2012 Trustwave Accelya UK Limited 11/18/2011 Trustwave Accertify, Inc. 2/28/2012 Halock Security Labs Accesso 4/9/2012 Trustwave AccountNow 6/28/2011 Trustwave Acculynk 3/24/2011 Trustwave ACH Direct (Payments Gateway) 2/1/2012 RSM McGladrey, Inc. ACI Worldwide - Winn-Dixie Environment 6/21/2011 Solutionary, Inc. ACI Worldwide (eps) AG 9/30/2011 FishNet Security ACI Worldwide, Inc. – Retail On Demand 6/19/2012 Solutionary, Inc. ACS, Inc. / BATA FasTrak 1/27/2012 SecurityMetrics Active Network / ActiveWorks Outdoors Divison (Infospherix, ReserveWorld) 10/31/2011 Protiviti Adelante Software Limited 4/4/2011 Convergent Network Solutions, L Adeptra 12/7/2011 Protiviti Adflex Limited 3/28/2011 Evolution LTD Advam Pty Ltd. -

2016 ACI Worldwide Annual Report

2016 ANNUAL REPORT ENABLING REAL-TIME ELECTRONIC PAYMENTS FOR ANYONE, ANYWHERE, AT ANY TIME The payments landscape is moving to real time, and ACI is leading the way. Our unique Universal Payments® (UP®) software powers global eCommerce by equipping financial institutions, intermediaries and merchants with the ability to deliver real-time, any-to-any payments that are reliable, efficient and highly secure. Available through ACI’s private cloud or managed on customers’ premises, UP solutions offer access to more payment endpoints and services than any other provider — enabling our customers to create the innovative products and services needed to stand out in today’s competitive market. 2016 marked an important year in the continued buildout of UP solutions for customers both in the cloud and on premise, with ACI answering the call for innovation across eCommerce, immediate payments, retail payments, transaction banking, bill payments and more.” Philip G. Heasley President and Chief Executive Officer FELLOW STAKEHOLDERS Decisions (ReD) and the 2015 acquisition of PAY.ON. This solution helps merchants overcome the challenges Electronic payment systems are the backbone of global of accepting locally-preferred payment methods as well commerce. These systems must function very quickly, as cross-border payments processing with integrated seamlessly, securely and reliably without regard to where fraud management. Since the launch, the solution has a transaction is initiated or completed. won numerous industry awards and seen rapid adoption throughout the world. Universal connectivity ACI’s Universal Payments (UP) solutions deliver the Milestone year for UP Retail Payments™ universal connectivity needed to make real-time electronic solution adoption payments possible by anyone, anywhere, at any time. -

Mpos Tracker™ Report AUGUST 2017

a mPOS Tracker™ report AUGUST 2017 MASTERCARD’S MPOS SHOT AT THE OPEN CHAMPIONSHIP Debuting in-seat delivery at the Open Championship, GASTROFIX achieves Find the top providers in powered by mPOS €15 million in funding the latest Tracker Scorecard – page 5 (Feature Story)5 – page 8 (News and8 Trends) – page 16 16 mPOS Tracker™ © 2017 PYMNTS.com all rights reserved Table of Contents PAGE What’s Inside A look at the quickly evolving mPOS space, and the latest news on expansion 03 efforts from mPOS providers. PAGE Feature Story Elliott Goldberg, head of digital payments for Mastercard U.K., on how the 05 company made mobile payments work at last month’s Open Championship. PAGE News and Trends 08 The latest headlines and trends from around the mPOS world. PAGE Top 25 Providers | Scorecard The results are in. See this month’s top scorers and a provider directory 15 featuring 283 major players in the space. PAGE About 155 Information on PYMNTS.com mPOS Tracker™ © 2017 PYMNTS.com all rights reserved August 2017 | 2 What’s Inside hile smartphones and other mobile devices are Also on the expansion front, California-base credit card a staple of American life in the 21st century, processor Square is continuing international efforts they’re even more popular abroad. That is in the U.K., where it recently celebrated the addition Wcertainly the case when it comes to the usage of mobile of partners TouchBistro and Vend to the Square U.K. wallets. Adoption rates in Europe and Asia far outpace platform. those in the U.S., thanks to consumers who are eager To read the rest of the latest news from around the for more modern payment methods in those regions. -

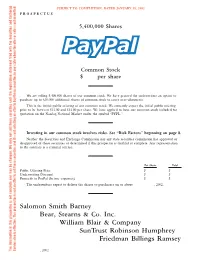

Paypal Prospectus.Pdf

SUBJECT TO COMPLETION, DATED JANUARY 18, 2002 P R O S P E C T U S 5,400,000 Shares Common Stock statement filed with the Securities and Exchange $ per share e securities in any state where the offer or sale is not permitted. We are selling 5,400,000 shares of our common stock. We have granted the underwriters an option to purchase up to 810,000 additional shares of common stock to cover over-allotments. This is the initial public offering of our common stock. We currently expect the initial public offering price to be between $12.00 and $14.00 per share. We have applied to have our common stock included for quotation on the Nasdaq National Market under the symbol ``PYPL.'' Investing in our common stock involves risks. See ``Risk Factors'' beginning on page 8. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission nor any state securities commission has approved or disapproved of these securities or determined if this prospectus is truthful or complete. Any representation to the contrary is a criminal offense. Per Share Total Public Offering Price $ $ Underwriting Discount $ $ Proceeds to PayPal (before expenses) $ $ The underwriters expect to deliver the shares to purchasers on or about , 2002. Salomon Smith Barney Bear, Stearns & Co. Inc. William Blair & Company SunTrust Robinson Humphrey Friedman Billings Ramsey The information in this prospectus is not complete and may be changed. We may not sell these securities until the registration The information in this prospectus is not complete and may be changed. We Commission is effective. This prospectus not an offer to sell these securities and it soliciting buy thes , 2002 You should rely only on the information contained in this prospectus. -

Survey of Developments in Electronic Money and Internet and Mobile Payments

Committee on Payment and Settlement Systems Survey of developments in electronic money and internet and mobile payments March 2004 Copies of publications are available from: Bank for International Settlements Press & Communications CH-4002 Basel, Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] Fax: +41 61 280 9100 and +41 61 280 8100 This publication is available on the BIS website (www.bis.org). © Bank for International Settlements 2004. All rights reserved. Brief excerpts may be reproduced or translated provided the source is cited. ISBN 92-9131-667-9 (print) ISBN 92-9197-667-9 (online) Foreword A number of innovative products for making payments have been developed in recent years, taking advantage of rapid technological progress and financial market development. Transactions made using these innovative products are accounting for an increasing proportion of the volume and value of domestic and cross-border retail payments. The possibility of electronic money taking over from physical cash for most small-value payments continues to evoke considerable interest among both the public and the various authorities concerned, including central banks. Although e-money has not been a very dynamic area in the field of retail payments recently, its development raises policy issues for central banks as regards payment system oversight, the possible implications for central banks’ revenues and the implementation of monetary policy. In view of these potential policy concerns, in 1996 the G10 central bank Governors announced their intention to closely monitor the evolution of electronic money schemes and products and, while respecting competition and innovation, to take any appropriate action if necessary. The Governors asked the BIS to monitor the developments of these new products on a regular and, as far as possible, global basis. -

Stifling Payments Innovation with Overregulation: Nonbanks Are Leading the Way in Payments Innovation Because Banks Are Stifled with Overregulation by Eric Grover

Stifling Payments Innovation with Overregulation: Nonbanks are leading the way in payments innovation because banks are stifled with overregulation by Eric Grover BAI Banking Strategies Magazine July 13, 2015 With the advent of Apple Pay and Android Pay, Bitcoin and EBay spinning off PayPal, payments are in the spotlight. But you’ve probably noticed that nonbanks have spearheaded most of this innovation, which wasn’t the case historically. Why is that? Banks in the modern form have existed since Renaissance Italy, when they evolved to play the central role in the payments system. The problem is that politics determines who can obtain a government charter to be a bank, the operating environment and associated rents. In Fragile By Design: The Political Origins of Banking Crises and Scarce Credit, Charles Calomiris and Stephen Haber describe this as the “Game of Bank Bargains,” by which banks negotiate the terms of banking with the political powers, whether under democratic or autocratic systems. As a result, banking is among the most heavily regulated and politicized industries, which puts a damper on innovation and makes the system more prone to crises. The aftermath of the 2008-2009 financial crisis provides a good example, when Washington’s regulatory grip tightened, putatively to prevent future crises. The hard and indirect costs of that tightening have been massive. Citibank alone admitted spending $180 million in the second half of 2014 submitting to the Fed’s stress tests. More worrying are management’s need to focus on Washington overlords rather than customers, new products and markets, the attendant opportunity costs and the stultifying effect on culture. -

Mobile Payments: What We Can Learn from the Past

Mobile Payments: what we can learn from the past By Gladys PRISO Diplomee de l'Institut de Management International de Paris, 1994 Submitted to MIT Sloan School of Management in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of: Master of Business Administration at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology June 2006 © 2006 Gladys PRISO. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part Signature of Author MIT Sloan School of Management May 16, 2006 Certified by Henry Birdseye Weil Thesis Supervisor Accepted by - Steven J. Sacca Director, Sloan Fellow Program MASSAC 8U i SrS- S W OF TECHNOLOGY AUG 3 12006 ARCHNIVES LIBRARIES Mobile Payments: what we learn from the past By Gladys PRISO Submitted to the MIT Sloan School of Management on May 16 2006 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Business Administration Massachusetts Institute of Technology Abstract Over the last decade, there has been a proliferation of mobile payments systems (MPS). Close to 150 MPS currently exist in the world according to the Bank for International Settlement records (BIS). Mobile payments (MP) markets are at different stages of development depending on countries. However, most of them are going through their embryonic or early phases. According to the theory, at this fluid stage, where no dominant design has emerged, it is nearly impossible to predict industry evolution. This paper tests the hypothesis that (i) because the MP industry is a path dependent system rather than a hysteresis system whose state depends on their immediate history, (ii) we can actually rely on accumulated experiences (success and failures) to narrow markets options in terms of dominant players and speed of adoption. -

Program and PCI the Mastercard Compliant Service Provider List

Site Data Protection (SDP) Program and PCI The Mastercard Compliant Service Provider List A company’s name appears on this Compliant Service Provider List if (i) Mastercard has received a copy of an Attestation of Compliance (AOC) by a Qualified Security Assessor (QSA) reflecting validation of the company being PCI DSS compliant and (ii) Mastercard records reflect the company is registered as a Service Provider by one or more Mastercard Customers. The date of the AOC and the name of the QSA are also provided. Each AOC is valid for one year. Mastercard receives copies of AOCs from various sources. This Compliant Service Provider List is provided solely for the convenience of Mastercard Customers and any Customer that relies upon or otherwise uses this Compliant Service Provider list does so at the Customer’s sole risk. While Mastercard endeavors to keep the list current as of the date set forth in the footer, Mastercard disclaims any and all warranties of any kind, including any warranty of accuracy or completeness or fitness for any particular purpose. Mastercard disclaims any and all liability of any nature relating to or arising in connection with the use of or reliance on the Compliant Service Provider List or any part thereof. Each Mastercard Customer is obligated to comply with Mastercard Rules and other Standards pertaining to use of a Service Provider. As a reminder, an AOC by a QSA provides a “snapshot” of security controls in place at a point in time. Compliant Service Provider 1-60 Days Past AOC Due Date 61-90 Days Past AOC Due Date Service Provider Name Region AOC Date Assessor DESV 1&1 Internet SE Europe 05/03/2018 Security Research & Consulting GmbH 1Link (Guarantee) Limited Asia Pacific 11/14/2017 Foregenix Limited 1Shoppingcart.com (Web.com Group, lnc.) US 05/25/2018 Payment Software Company (PSC) 2138617 Ontario Inc. -

RTF Template

Protokoll-Nr. 18/50 18. Wahlperiode Ausschuss Digitale Agenda Wortprotokoll der 50. Sitzung Ausschuss Digitale Agenda Berlin, den 11. November 2015, 16:00 Uhr 11011 Berlin, Konrad-Adenauer-Str. 1 Sitzungssaal: PLH E.200 Vorsitz: Jens Koeppen, MdB Tagesordnung - Öffentliche Anhörung Tagesordnungspunkt 1 Seite 07 Öffentliches Fachgespräch zum Thema: Digitalisierung in der Finanzwirtschaft a) Geänderte Liste der Sachverständigen Ausschussdrucksache 18(24)SB21neu b) Fragenkatalog Ausschussdrucksache 18(24)SB22 18. Wahlperiode Seite 1 von 30 Ausschuss Digitale Agenda Mitglieder des Ausschusses Ordentliche Mitglieder Stellvertretende Mitglieder CDU/CSU Beermann, Maik Hornhues, Bettina Durz, Hansjörg Lange, Ulrich Jarzombek, Thomas Schön (St. Wendel), Nadine Koeppen, Jens Tauber, Dr. Peter Nick, Dr. Andreas Wanderwitz, Marco Schipanski, Tankred Wendt, Marian Schwarzer, Christina Whittaker, Kai SPD Esken, Saskia Bartol, Sören Flisek, Christian Dörmann, Martin Klingbeil, Lars Heidenblut, Dirk Reichenbach, Gerold Stadler, Svenja Zimmermann, Dr. Jens Träger, Carsten DIE LINKE. Behrens, Herbert Korte, Jan Wawzyniak, Halina Pau, Petra BÜNDNIS 90/DIE Janecek, Dieter Beck (Köln), Volker GRÜNEN Notz, Dr. Konstantin von Rößner, Tabea 18. Wahlperiode Protokoll der 50. Sitzung Seite 2 von 30 vom 11. November 2015 Ausschuss Digitale Agenda 18. Wahlperiode Protokoll der 50. Sitzung Seite 3 von 30 vom 11. November 2015 Ausschuss Digitale Agenda 18. Wahlperiode Protokoll der 50. Sitzung Seite 4 von 30 vom 11. November 2015 Ausschuss Digitale Agenda 18. Wahlperiode Protokoll der 50. Sitzung Seite 5 von 30 vom 11. November 2015 Ausschuss Digitale Agenda 18. Wahlperiode Protokoll der 50. Sitzung Seite 6 von 30 vom 11. November 2015 Ausschuss Digitale Agenda Tagesordnungspunkt 1 aber gerade zu diesem Thema haben wir in dieser Woche eine sehr wichtige Entscheidung getroffen.