Understanding Risk Management in Emerging Retail Payments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Financial Literacy and Portfolio Diversification

WORKING PAPER NO. 212 Financial Literacy and Portfolio Diversification Luigi Guiso and Tullio Jappelli January 2009 University of Naples Federico II University of Salerno Bocconi University, Milan CSEF - Centre for Studies in Economics and Finance DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS – UNIVERSITY OF NAPLES 80126 NAPLES - ITALY Tel. and fax +39 081 675372 – e-mail: [email protected] WORKING PAPER NO. 212 Financial Literacy and Portfolio Diversification Luigi Guiso and Tullio Jappelli Abstract In this paper we focus on poor financial literacy as one potential factor explaining lack of portfolio diversification. We use the 2007 Unicredit Customers’ Survey, which has indicators of portfolio choice, financial literacy and many demographic characteristics of investors. We first propose test-based indicators of financial literacy and document the extent of portfolio under-diversification. We find that measures of financial literacy are strongly correlated with the degree of portfolio diversification. We also compare the test-based degree of financial literacy with investors’ self-assessment of their financial knowledge, and find only a weak relation between the two measures, an issue that has gained importance after the EU Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MIFID) has required financial institutions to rate investors’ financial sophistication through questionnaires. JEL classification: E2, D8, G1 Keywords: Financial literacy, Portfolio diversification. Acknowledgements: We are grateful to the Unicredit Group, and particularly to Daniele Fano and Laura Marzorati, for letting us contribute to the design and use of the UCS survey. European University Institute and CEPR. Università di Napoli Federico II, CSEF and CEPR. Table of contents 1. Introduction 2. The portfolio diversification puzzle 3. The data 4. -

The Challenges of Risk Management in Diversified Financial Companies

Christine M. Cumming and Beverly J. Hirtle The Challenges of Risk Management in Diversified Financial Companies • Although the benefits of a consolidated, or n recent years, financial institutions and their supervisors firmwide, system of risk management are Ihave placed increased emphasis on the importance of widely recognized, financial firms have consolidated risk management. Consolidated risk traditionally taken a more segmented management—sometimes also called integrated or approach to risk measurement and control. enterprisewide risk management—can have many specific meanings, but in general it refers to a coordinated process for • The cost of integrating information across measuring and managing risk on a firmwide basis. Interest in business lines and the existence of regulatory consolidated risk management has arisen for a variety of barriers to moving capital and liquidity within reasons. Advances in information technology and financial a financial organization appear to have engineering have made it possible to quantify risks more discouraged firms from adopting consolidated precisely. The wave of mergers—both in the United States and risk management. overseas—has resulted in significant consolidation in the financial services industry as well as in larger, more complex financial institutions. The recently enacted Gramm-Leach- • In addition, there are substantial conceptual Bliley Act seems likely to heighten interest in consolidated risk and technical challenges to be overcome in management, as the legislation opens the door to combinations developing risk management systems that of financial activities that had previously been prohibited. can assess and quantify different types of risk This article examines the economic rationale for managing across a wide range of business activities. -

Financial Risk Management Insights CGI & Aalto University Collaboration

Financial Risk Management Insights CGI & Aalto University Collaboration Financial Risk Management Insights - CGI & Aalto University Collaboration ABSTRACT As worldwide economy is facing far-reaching impacts aggravated by the global COVID-19 pandemic, the financial industry faces challenges that exceeds anything we have seen before. Record unemployment and the likelihood of increasing loan defaults have put significant pressure on financial institutions to rethink their lending programs and practices. The good news is that financial sector has always adapted to new ways of working. Amidst the pandemic crisis, CGI decided to collaborate with Aalto University in looking for ways to challenge conventional ideas and coming up with new, innovative approaches and solutions. During the summer of 2020, Digital Business Master Class (DBMC) students at Aalto University researched the applicability and benefits of new technologies to develop financial institutions’ risk management. The graduate-level students with mix of nationalities and areas of expertise examined the challenge from multiple perspectives and through business design methods in cooperation with CGI. The goal was to present concept level ideas and preliminary models on how to predict and manage financial risks more effectively and real-time. As a result, two DBMC student teams delivered reports outlining the opportunities of emerging technologies for financial institutions’ risk assessments beyond traditional financial risk management. 2 CONTENTS Introduction 4 Background 5 Concept -

Systemic Moral Hazard Beneath the Financial Crisis

Seton Hall University eRepository @ Seton Hall Law School Student Scholarship Seton Hall Law 5-1-2014 Systemic Moral Hazard Beneath The inF ancial Crisis Xiaoming Duan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.shu.edu/student_scholarship Recommended Citation Duan, Xiaoming, "Systemic Moral Hazard Beneath The inF ancial Crisis" (2014). Law School Student Scholarship. 460. https://scholarship.shu.edu/student_scholarship/460 The financial crisis in 2008 is the greatest economic recession since the "Great Depression of the 1930s." The federal government has pumped $700 billion dollars into the financial market to save the biggest banks from collapsing. 1 Five years after the event, stock markets are hitting new highs and well-healed.2 Investors are cheering for the recovery of the United States economy.3 It is important to investigate the root causes of this failure of the capital markets. Many have observed that the sudden collapse of the United States housing market and the increasing number of unqualified subprime mortgages are the main cause of this economic failure. 4 Regulatory responses and reforms were requested right after the crisis occurred, as in previous market upheavals where we asked ourselves how better regulation could have stopped the market catastrophe and prevented the next one. 5 I argue that there is an inherent and systematic moral hazard in our financial systems, where excessive risk-taking has been consistently allowed and even to some extent incentivized. Until these moral hazards are eradicated or cured, our financial system will always face the risk of another financial crisis. 6 In this essay, I will discuss two systematic moral hazards, namely the incentive to take excessive risk and the incentive to underestimate risk. -

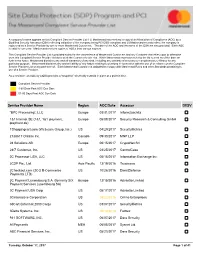

Service Provider Name Region AOC Date Assessor DESV

A company’s name appears on this Compliant Service Provider List if (i) Mastercard has received a copy of an Attestation of Compliance (AOC) by a Qualified Security Assessor (QSA) reflecting validation of the company being PCI DSS compliant and (ii) Mastercard records reflect the company is registered as a Service Provider by one or more Mastercard Customers. The date of the AOC and the name of the QSA are also provided. Each AOC is valid for one year. Mastercard receives copies of AOCs from various sources. This Compliant Service Provider List is provided solely for the convenience of Mastercard Customers and any Customer that relies upon or otherwise uses this Compliant Service Provider list does so at the Customer’s sole risk. While Mastercard endeavors to keep the list current as of the date set forth in the footer, Mastercard disclaims any and all warranties of any kind, including any warranty of accuracy or completeness or fitness for any particular purpose. Mastercard disclaims any and all liability of any nature relating to or arising in connection with the use of or reliance on the Compliant Service Provider List or any part thereof. Each Mastercard Customer is obligated to comply with Mastercard Rules and other Standards pertaining to use of a Service Provider. As a reminder, an AOC by a QSA provides a “snapshot” of security controls in place at a point in time. Compliant Service Provider 1-60 Days Past AOC Due Date 61-90 Days Past AOC Due Date Service Provider Name Region AOC Date Assessor DESV “BPC Processing”, LLC Europe 03/31/2017 Informzaschita 1&1 Internet SE (1&1, 1&1 ipayment, Europe 05/08/2017 Security Research & Consulting GmbH ipayment.de) 1Shoppingcart.com (Web.com Group, lnc.) US 04/29/2017 SecurityMetrics 2138617 Ontario Inc. -

View Annual Report

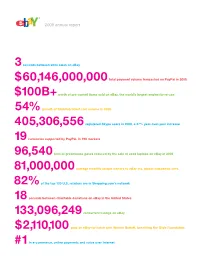

To Our Stockholders, In 2008, we embraced a tremendous amount of fundamental change against the backdrop of a deteriorating external market and economy. Even with the challenges, we exited the year a stronger company and remain a leader in e-commerce, payments and Internet voice communications. Our performance for the full year not only reflects the strength of our portfolio, but also the operating discipline, strategic clarity and focus with which our management team is leading the company going forward. Financially, the company had a good year, marked by strong revenue growth, stronger EPS growth and excellent free cash flow. Despite the extremely challenging economic environment in 2008 – including a slowdown in global e-commerce, a strengthening dollar, and declining interest rates – we delivered $8.5 billion in revenues, an 11 percent increase from the prior year, and $1.36 of diluted EPS. We also delivered a solid operating margin of 24 percent. The size of the eBay marketplace continues to be the largest in the world with nearly $60 billion of gross merchandise volume (the total value of goods sold in all of our Marketplaces) in 2008. PayPal continues to experience strong growth, both on eBay and across e-commerce, and Skype had a great year, growing both revenues and user base. In addition, we strengthened our portfolio by investing in the growth of our emerging businesses and through key acquisitions. In 2008, advertising, global classifieds and StubHub, the leading online tickets marketplace, all gained momentum in terms of revenues. Key acquisitions we made during the year will help us build on our strengths. -

Paypal Welneteller.Com Neteller.Com Member.Neteller.Com

List of websites compiled from browser history, categorized by area of interest: FINANCE GAMBLING E-COMMERCE DATING OTHER paypal pokerstars store.apple.com cupid.com whoer.net welneteller.com unibet.com newegg.com zoosk steampowered.com neteller.com LuckyAcePoker.com bestbuy.com meetic yahoo.com member.neteller.com fulltiltpoker.com amazon.com match.com gmail.com moneybookers.com www.parispokerclub.fr ebay meetme.com mail.google.com webmoney.ru partypoker.com bhphotovideo.com date.com indeed.com westernunion poker.770.com swiftunlocks.com sendspace.com wellsfargo.com 770.com target.com hotmail.com coinbase.com 770poker.com airbnb.com skype.com perfectmoney.com bwin.com walmart adwords.google.com liqpay.com betfair.com lowes airbnb.com payeer.com 32redpoker.com qvc.com datehookup.com entropay.com amateurmatch.com sears.com open24.ie suntrust.com titanpoker.com business.att.com aib.ie skrill.com ipoker.com ebillplace.com ups.com paysurfer.com bet365.com capitalone.com starbucks chase.com 888poker.com verizonwireless.com craiglist.org chaseonline.chase.com www.fulltilt.eu att.com exoclick.com money.yandex.ru 188bet.com barclaycardus.com plugrush.com qiwi.com leonbets.net leaseville.com zeropark.com paysafecard.com paysurfer.com officedepot.com juicyads.com sportingbet.ru sprint.com popads.net sportingbet.com verizon.com expedia.com betsson.no vzw.com expedia.no williamhill.com northskull.com expedia.se bwin.es keller-sports.de accurint.com bwin.com farfetch.com kohls.com netbet.co.uk playerauctions.com hottopic.com netbet.com circle.com pacmall.net paddypower.com. -

How People Pay Australia to Brazil

HowA BrandedPay™ StudyPeople of Multinational Attitudes Pay Around Shopping, Payments, Gifts and Rewards Contents 01 Introduction 03 United States 15 Canada 27 Mexico 39 Brazil 51 United Kingdom 63 Germany 75 Netherlands 87 Australia 99 Changes Due to COVID-19 This ebook reflects the findings of online surveys completed by 12,009 adults between February 12 and March 17, 2020. For the COVID-19 addendum section, 1,096 adults completed a separate online survey on May 21, 2020. Copyright © 2020 Blackhawk Network. There are also some trends that are impossible to ignore. Shopping and making payments through entirely digital channels is universal and growing, from How People Pay Australia to Brazil. A majority of respondents in every region say that they shop online more often than they shop in stores. This trend is most pronounced in younger generations and in Latin American countries, but it’s an essential fact Our shopping behaviors are transforming. How people shop, where they shop and across all demographic groups and in every region. how they pay are constantly in flux—and the trends and patterns in those changes reveal a lot about people. After all, behind all of the numbers and graphs are the In the rest of this BrandedPay report, you’ll find a summary and analysis of trends people. People whose varied tastes, daily lives and specific motivations come in each of our eight surveyed regions. We also included a detailed breakdown of together to form patterns and trends that shape global industries. how people in that region answered the survey, including any traits specific to that region. -

Supreme Court of the United States

No. 17-1104 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States AIR AND LIQUID SYSTEMS CORP., et al., Petitioners, v. ROBERTA G. DEVRIES, INDIVIDUALLY AND AS ADMINISTRATRIX OF THE ESTATE OF JOHN B. DEVRIES, DECEASED, et al., Respondents. –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– INGERSOLL RAND COMPANY , Petitioner, v. SHIRLEY MCAFEE, EXECUTRIX OF THE ESTATE OF KENNETH MCAFEE, AND WIDOW IN HER OWN RIGHT, Respondent. ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES CouRT OF APPEALS FOR THE THIRD CIRcuIT BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS DENYSE F. CLANCY RicHARD P. MYERS KAZAN, MCCLAIN, SATTERLEY Counsel of Record & GREENWOOD ROBERT E. PAUL 55 Harrison Street, Suite 400 ALAN I. REicH Oakland, CA 94607 PATRick J. MYERS (877) 995-6372 PAUL, REicH & MYERS, P.C. [email protected] 1608 Walnut Street, Suite 500 Philadelphia, PA 19103 (215) 735-9200 [email protected] Counsel for Respondents (Additional Counsel Listed on Inside Cover) 281732 JONATHAN RUckdESCHEL WILLIAM W.C. HARTY THE RUckdESCHEL LAW PATTEN, WORNOM, HATTEN FIRM, LLC & DIAMONSTEIN 8357 Main Street 12350 Jefferson Avenue, Ellicott City, MD 21043 Suite 300 (410) 750-7825 Newport News, VA 23602 [email protected] (757) 223-4500 [email protected] Counsel for Respondents i QUESTION PRESENTED Under general maritime negligence law, does a manufacturer have a duty to warn users of the known hazards arising from the expected and intended use of its own product? ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page QUESTION PRESENTED .......................i TABLE OF CONTENTS......................... ii TABLE OF APPENDICES .....................viii TABLE OF CITED AUTHORITIES ...............x INTRODUCTION ...............................1 COUNTER STATEMENT OF THE CASE .........6 A. Respondents were exposed to asbestos during the expected and intended use of petitioners’ machines ..................6 1. -

Customer Advisory: Beware Virtual Currency Pump-And-Dump Schemes

Customer Advisory: Beware Virtual Currency Pump-and-Dump Schemes The U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) is advising customers to avoid pump-and-dump schemes that can occur in thinly traded or new “alternative” virtual currencies and digital coins or tokens. Customers should not purchase virtual currencies, digital coins, or tokens based on social media tips or sudden price spikes. Thoroughly research virtual currencies, digital coins, tokens, and the companies or entities behind them in order to separate hype from facts. Blow the whistle on Pump-and-dump schemes have been around long pump-and-dump schemers before virtual currencies and digital tokens. Historically, they were the domain of “boiler room” Virtual currency and digital token pump- frauds that aggressively peddled penny stocks by and-dump schemes continue because falsely promising the companies were on the verge they are mostly anonymous. of major breakthroughs, releasing groundbreaking If you have original information that products, or merging with blue chip competitors. As leads to a successful enforcement demand in the thinly traded companies grew, the action that leads to monetary sanctions share prices would rise. When the prices reached a of $1 million or more, you could be certain point, the boiler rooms would dump their eligible for a monetary award of remaining shares on the open market, the prices between 10 percent and 30 percent. would crash, and investors were left holding nearly For more information, or to submit a tip, worthless stock. visit the CFTC’s whistleblower.gov website. Old Scam, New Technology The same basic fraud is now occurring using little known virtual currencies and digital coins or tokens, but thanks to mobile messaging apps or Internet message boards, today’s pump-and- dumpers don’t need a boiler room, they organize anonymously and hype the currencies and tokens using social media. -

Using Clawback Actions to Harvest the Equitable Roots of Bankrupt Ponzi Schemes Jessica D

Georgia State University College of Law Reading Room Faculty Publications By Year Faculty Publications 1-1-2011 Midnight in the Garden of Good Faith: Using Clawback Actions to Harvest the Equitable Roots of Bankrupt Ponzi Schemes Jessica D. Gabel Georgia State University College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/faculty_pub Part of the Accounting Law Commons, Bankruptcy Law Commons, and the Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons Recommended Citation Jessica D. Gabel, Midnight in the Garden of Good Faith: Using Clawback Actions to Harvest the Equitable Roots of Bankrupt Ponzi Schemes, 62 Case W. Res. L. Rev. 19 (2011). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Reading Room. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications By Year by an authorized administrator of Reading Room. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES MIDNIGHT IN THE GARDEN OF GOOD FAITH: USING CLAWBACK ACTIONS TO HARVEST THE EQUITABLE ROOTS OF BANKRUPT PONZI SCHEMES JessicaD. Gabelt CONTENTS INTRODUCTION: Too GOOD TO BE "GOOD FAITH"....................20 I. THE PONzI KINGDOM: STITCHING THE EMPEROR'S NEW CLOTHES ................................................................... 25 A. Ponzi Construction Codes ............................................ 25 B. Historic Ponzi Schemes.........................26 11. THE CLAWBACK CROWD: IN PURSUIT OF PONZI PAYOUTS .... 30 A. Ponzi Scheme Definition and Its Players................ 31 B. Ponzi Payouts:"Fraudulent or Preferential?.............. 32 1. Defining andDifferentiating Fraudulent Transfers..... 34 2. Ponzi Schemes: Fraud in the Making................ 36 t Assistant Professor of Law, Georgia State University College of Law. J.D., University of Miami School of Law; B.S., University of Central Florida. -

Part 1 Structure and Working of Boiler Rooms Scams

Frans Roest: E-BOOK EDITION Share Fraud & Boiler Room Scams Exposed A research about worldwide boiler room share fraud __________________________________________________________________________________________ PART 1 STRUCTURE AND WORKING OF BOILER ROOMS SCAMS Frans Roest: E-BOOK EDITION Share Fraud & Boiler Room Scams Exposed A research about worldwide boiler room share fraud __________________________________________________________________________________________ 1.0 Introduction and scope of the problem 1.1 Introduction In this study we look at a specific form of international investment share scams, the criminal act of selling worthless shares, non-existing shares or other financial derivatives using high pressure sales tactics such as cold calling, or through mediums like e-mail and the internet. The efficiently structured boiler room represents just one of the many types of groups that perpetrate mass- marketing fraud. It is the authors’ opinion that boiler room/stock fraud scams are underestimated due to the fact that to this day, most national governments still do not know how to adequately address this international form of organised crime. An Australian report about serious and organised investment fraud states that one of the main challenges in developing responses to such activities is the lack of available tried and proven practical examples.1 In this study the author hopes to fill this gap to some extent. This study describes international impressions in the campaign against boiler room fraud worldwide and also a number of ‘good practices’ in the field of prevention and information from, amongst others, Australia, Canada, Great Britain, The Netherlands, Spain, Hong Kong, USA and, more recently, New Zealand. This information has been derived from open sources (public domain information).