Between Policy, Parties, Press and Public Opinion in 2007 Desirée M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rifondazione Comunista Dallo Scioglimento Del PCI Al “Movimento Dei Movimenti”

C. I. P. E. C., Centro di iniziativa politica e culturale, Cuneo L’azione politica e sociale senza cultura è cieca. La cultura senza l’azione politica e sociale è vuota. (Franco Fortini) Sergio Dalmasso RIFONDARE E’ DIFFICILE Rifondazione comunista dallo scioglimento del PCI al “movimento dei movimenti” Quaderno n. 30. Alla memoria di Ludovico Geymonat, Lucio Libertini, Sergio Garavini e dei/delle tanti/e altri/e che, “liberamente comunisti/e”, hanno costruito, fatto crescere, amato, odiato...questo partito e gli hanno dato parte della loro vita e delle loro speranze. Introduzione Rifondazione comunista nasce nel febbraio del 1991 (non adesione al PDS da parte di alcuni dirigenti e di tanti iscritti al PCI) o nel dicembre dello stesso anno (fondazione ufficiale del partito). Ha quindi, in ogni caso, compiuto i suoi primi dieci anni. Sono stati anni difficili, caratterizzati da scadenze continue, da mutamenti profondi del quadro politico- istituzionale, del contesto economico, degli scenari internazionali, sempre più tesi alla guerra e sempre più segnati dall’esistenza di una sola grande potenza militare. Le ottimistiche previsioni su cui era nato il PDS (a livello internazionale, fine dello scontro bipolare con conseguente distensione e risoluzione di gravi problemi sociali ed ambientali, a livello nazionale, crescita della sinistra riformista e alternanza di governo con le forze moderate e democratiche) si sono rivelate errate, così come la successiva lettura apologetica dei processi di modernizzazione che avrebbero dovuto portare ad un “paese normale”. Il processo di ricostruzione di una forza comunista non è, però, stato lineare né sarebbe stato possibile lo fosse. Sul Movimento e poi sul Partito della Rifondazione comunista hanno pesato, sin dai primi giorni, il venir meno di ogni riferimento internazionale (l’elaborazione del lutto per il crollo dell’est non poteva certo essere breve), la messa in discussione dei tradizionali strumenti di organizzazione (partiti e sindacati) del movimento operaio, la frammentazione e scomposizione della classe operaia. -

Composizione Del Governo Prodi

Confederazione Generale Italiana dei Trasporti e della Logistica 00198 Roma - via Panama 62 - tel. 06/8559151 - fax 06/8415576 e-mail: [email protected] - http://www.confetra.com Roma, 25 maggio 2006 Circolare n.61/2006 Oggetto: Composizione del Governo Prodi. Si riporta la composizione del Governo Prodi con riferimento a Ministri, a Vice Mini- stri e Sottosegretari di più diretto interesse per i settori rappresentati dalla Confe- tra. Per ciascun nominativo viene indicato luogo e data di nascita nonché, qualora trattasi di componente del Parlamento, partito di appartenenza e circoscrizione elet- torale. f.to dr. Piero M. Luzzati Per riferimenti confronta circ.re conf.le n.51/2005 Lo/lo © CONFETRA – La riproduzione totale o parziale è consentita esclusivamente alle organizzazioni aderenti alla Confetra. PRESIDENZA DEL CONSIGLIO Presidente: on. Romano Prodi (Ulivo) Scandiano (RE) 1939 – Circoscrizione XI (Emilia Romagna) Vice Presidenti: • on. Massimo D’Alema (DS) Roma 1949 – Circoscrizione XXI (Puglia) • on. Francesco Rutelli (Margherita) Roma 1954 – Circoscrizione XV (Lazio I) Sottosegretari: • on. Enrico Letta (Margherita) Pisa 1966 – Circoscrizione III (Lombardia I) • dr. Enrico Micheli Terni 1938 – Già deputato della Margherita nella precedente legislatura • prof. Fabio Gobbo Venezia 1947 • on. Ricardo Franco Levi (Ulivo) Montevideo (Uruguay) 1949 – Circoscrizione III (Lombardia I) MINISTERO DEI TRASPORTI Ministro: prof. ing. Alessandro Bianchi Roma 1945 - Rettore dell’Università degli Studi di Reggio Calabria e Professore ordinario di Urbanistica Vice Ministro: • on. Cesare De Piccoli (DS) Casale sul Sile (TV) 1946 – Circoscrizione VIII (Veneto II) Sottosegretario: • avv. Andrea Annunziata San Marzano sul Sarno (SA) 1955 - Già deputato della Margherita nella precedente legislatura 1 MINISTERO DELLE INFRASTRUTTURE Ministro: on. -

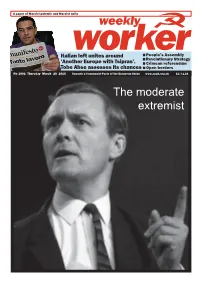

Weekly Worker March 13), Which of How I Understand the “From of Polemic

A paper of Marxist polemic and Marxist unity weekly Italian left unites around n People’s Assembly workern Revolutionary Strategy ‘Another Europe with Tsipras’. n Crimean referendum Tobe Abse assesses its chances n Open borders No 1002 Thursday March 20 2014 Towards a Communist Party of the European Union www.cpgb.org.uk £1/€1.10 The moderate extremist 2 weekly March 20 2014 1002 worker LETTERS Letters may have been in the elemental fight over wages definitively assert what he would What nonsense. Let us leave such shortened because of and conditions that would occur in Xenophobic have said then!” True enough (and window dressing to the Trots! space. Some names class society even if there was no I cannot escape the conclusion that fortunately for him nor was there Those on the left should ensure may have been changed such thing as Marxism. The fact that there exists a nasty xenophobic any asylum-seekers legislation for that those they employ are paid today “the works of Marx, Lenin undertone to Dave Vincent’s reply political refugees), but Eleanor, his transparently, in line with the Not astounding and others [are] freely available (Letters, March 13). daughter, was particularly active in market rate, and ensure best value In spite of all the evidence that I have on the internet” changes nothing in First, has Dave never heard of the distributing the statement, “The voice for money for their members. Crow put forward from Lars T Lih’s study, this regard, except for the fact that Irish immigration to Scotland and of the aliens’, which I recommended fulfilled all those requirements, Lenin rediscovered, in particular, uploading material onto a website in particular to the Lanarkshire coal as a read. -

Rifondazione and Europe: a Party Competition Analysis

Rifondazione and Europe: A party competition analysis Giorgos Charalambous Department of Politics University of Manchester [email protected] Paper prepared to be presented at the 58th Political Studies Association, Annual Conference, Swansea (UK), April 1-3. 1 Copyright PSA 2008 Abstract This paper adresses the attitude of Rifondazione Comunista on Europe (European Integration and the European Union) between 1992 and 2006. This is done through an analysis of its positions and institutional action in the Italian electoral arena and partly based on common assumptions and analytical frameworks of the prevailing literature; that is, party system analysis. Findings show that Rifondazione has achieved two things, that are almost in direct contradiction with each other. Firstly, it gradually increased the use of the issue of European integration to emphasise its radical identity, target the Eurosceptics and other radical sections of the electorate and differentiate itself as clearly as possible from the centre-left. Secondly, it underwent positional reallaignment towards a softer approach, mostly, throgh its voting behavior in the Italian parliament and its support for the centre-left governments. A broad discussion assesses the findings of this case study and illuminates larger questions about party attitudes towards European integration. 2 Copyright PSA 2008 INTRODUCTION Apart from being a study which attempts to provide insights into the tactical and strategic considerations of parties, when Europe is put on the agenda, a study of Rifondazione Comunista's electoral attitude towards European integration merits attention due to three main reasons. Firstly, Rifondazione Comunista's first fifteen years coincided with the 'intensive years' of European integration. -

Ma Per Chi Vota Fausto?

Ma per chi vota Fausto? Per chi vota Fausto Bertinotti? Domanda e curiosità sono più che legittime. Tutti i leader appartati negli ultimi anni dalla politica attiva si sono già espressi: Romano Prodi, Francesco Rutelli, Walter Veltroni e altri ancora. Alle dichiarazioni pubbliche in questi ultimi giorni di campagna elettorale manca in effetti quella di Bertinotti. E pare che non ci sarà alcun atto pubblico da parte sua per riserbo e per evitare polemiche, pur se alcuni indizi indicano che l’ex segretario di Rifondazione voterà la lista di Potere al popolo. Tra i promotori di quest’ultimo raggruppamento, insieme a centri sociali e movimenti, ci sono del resto Maurizio Acerbo e Paolo Ferrero, attuale segretario ed ex segretario di Rifondazione, successori di Bertinotti alla guida del partito lasciato nel 2008. L’ex presidente della camera non ha tuttavia particolari rapporti con quest’area, ma ne ha sicuramente meno con i promotori di Liberi e uguali nonostante Nichi Vendola e Nicola Fratoianni (ex Sinistra ecologia e libertà, poi Sinistra italiana) siano stati a lungo in sintonia con le sue posizioni: gli scambi di opinione sono però diventati con il tempo sempre più rari. Stima e ancora più distanza da Pietro Grasso e Massimo D’Alema, verso i quali c’è una profonda divisione sull’analisi della portata della sconfitta storica della sinistra e sulle modalità di una possibile ricostruzione. Bertinotti avrebbe confidato solo agli amici più intimi le proprie intenzioni di voto. I suoi collaboratori più stretti – quelli del nucleo della rivista Alternative per il socialismo da lui diretta, per esempio – avrebbero lo stesso orientamento pro Potere al popolo. -

Ciao Albert! Non Ti Dimenticheremo Mai!

RESISTENZA SOCIALE E MEDIATTIVISIMO CIAO ALBERT! NON TI DIMENTICHEREMO MAI! N° O3 2008 SOMMARIO ...............................................1 SEI BRILLANTI GIORNALISTE ....................7 EDITORIALE ...............................................2 Pillole DI contro INFormaZIONE .......8 QUALE SCENARIO A SINISTRA? .................3 INTERVISTA CLANDESTINA .......................3 AUTONOMIA! .............................................4 TROSKISMO ITALIANO............................. 5 all’amministrazione dell’esistente. Non è vero come afferma qualche sedicente e saccente intellettualoide di sinistra che il capitalismo non abbia valori. I valori gli ha e gli ha affermati anche con facilità per assenza di una vera alternativa alla soci- età. Se non si parlerà di socialismo per il XXI secolo il capitalismo nonostante le sue contraddizioni e i suoi limiti si trascinerà avanti nel tempo continuando a regalare illusioni e sofferenze all’intera umanità. L’autocritica degli sconfitti alle elezioni è finalizzata alla riconquista delle poltrone perse per questo non viene fatta in mare aperto sciogliendo nodi strategi- ci ma navigando a vista cercando nuove geometrie politiche al chiuso di stanze grigie di partiti che nella migliore delle ipotesi sono subalterni all’esistente. La continua ricerca del compromesso, tra l’altro da posizioni sempre più svantaggi- ose, con una presunta quanto inesistente borghesia buona è la riprova che i par- Editoriale rucconi della sinistra non hanno capito un CAZZO (idioti) o che forse lo hanno Mai come in questo periodo logica non trovano altra speranza che ap- capito bene (malafede)! Se non sarà lan- e realtà sono state cosi lontane tra pigliarsi alla fede. L’oppio dei popo- ciata una controffensiva culturale imme- loro. Tutte le analisi, i ragionamenti, li torna in gran voga anche in quello diata in Italia nello specifico e in Europa le verifiche e le riflessioni ci portano che una volta si chiamava occidente più in generale assisteremo al ritorno del ad una sola e unica conclusione ma illuminista. -

Direzione Nazionale. Archivio Fotografico

DIREZIONE NAZIONALE. ARCHIVIO FOTOGRAFICO FOTOGRAFIE CARTACEE 1. Nilde Guiducci. America Latina, docc. 27 (1) Immagini di manifestazioni, con molti ritratti. Altri ritratti realizzati da Nilde Guiducci in Chapas Fotografie B/N da 17,4x24 a 23,5x30; fotografia colore 10,5x15,5 Fotografie versate da Nilde Guiducci a Flavia Fasano. s.d. 2. Mexico, docc. 2 (2) Immagini di una manifestazione in Messico. Diapositive colore 5x5 Diapositive versate da Elisa Romagnoli s.d. 3. Giovane comunista, docc. 1 (3) Immagine di una giovane militante utilizzata per un manifesto dei giovani comunisti. Fotografia colore 10x14 Fotografia versata da Nunzia Lombardi. [ante 2001] 4. Lavorare tutti lavorare meno, docc. 46 (4) 5 fotografie rappresentano uno striscione con la scritta "Lavorare tutti lavorare meno. 25 settembre manifestazione naz.le p.zza S. Giovanni". Le restani 41 fotografie sono immagini con diversi soggetti che vanno dal paesaggio al ritratto. Fotografie B/N 10x14 ante 1998 5. Teatro Eliseo. Brancaccio. Palaeur. I Congresso e varie, docc. 44 (5) L'unità archivistica contiene immagini che documentano diverse fasi del Partito della rifondazione comunista: dai momenti antecedenti alla fondazione al I Congresso, alle manifestazioni di piazza. Molte fotografie documentano le attività dei circoli locali: dalle feste di liberazione, alle assemblee, alle elezioni comunali e regionali alle partite di calcio. Nelle immagini si riconoscono tra gli altri: Lucio Libertini, Armando Cossutta, Sergio Garavini, Dacia Valent, Nichi Vendola, Sandro Valentini, Luciano Pettinari, Giovanni Russo Spena, Ramon Mantovani, Walter de Cesaris, Alfio Nicotra, Abdullah Ocalan. Fotografie colore da 10x15 a 12,5x17,5; fotografie B/N da 12x17,5 a 14x19 Da materiale per l'Almanacco decennale, inviato perlopiù dai militanti dei territori a Flavia Fasano. -

CONTRO I SACRIFICI RIVOLTA GENERALE Editoriale Europa, Contro I Propri Lavoratori, Senza Bisogno Proporzionale All’Attacco

il giornale dei COMUNISTA lavoratori N° 1/2012 Gennaio/Febbraio www.pclavoratori.it € 2 CONTRO I SACRIFICI RIVOLTA GENERALE Editoriale Europa, contro i propri lavoratori, senza bisogno proporzionale all’attacco. Scioperi simbolici di dei consigli “patriottici” e sciovinisti della propaganda, o semplici azioni di resistenza in La manovra economica di fi ne anno è la carta sinistra cosiddetta “radicale”. Ed è per servire la ordine sparso, sono del tutto inadeguati, oggi d’identità del governo Monti. Un governo propria borghesia nella competizione mondiale ancor più di ieri. Occorre unifi care l’intero mondo nato con l’incarico di fare ciò che nessun che il governo annuncia una nuova offensiva del lavoro, dei precari, dei disoccupati attorno ad altro avrebbe potuto fare, sta rispettando contro l’articolo 18 e per la liberalizzazione una piattaforma generale di lotta che ponga al religiosamente il suo mandato. L’attacco portato dei licenziamenti. In perfetta sintonia con centro dello scontro le rivendicazioni operaie e alle condizioni sociali del lavoro dipendente l’aggressione sociale della Fiat e del padronato. popolari: a partire dal blocco dei licenziamenti, e della maggioranza della società italiana è la cancellazione delle leggi di precarizzazione, la di portata dirompente. La combinazione di UN FRONTE UNICO DI OPPOSIZIONE A ripartizione fra tutti del lavoro esistente, un vero distruzione delle pensioni di anzianità, blocco MONTI E AL PD salario sociale ai disoccupati, un grande piano di della rivalutazione delle pensioni, tassazione opere sociali fi nanziato da chi non ha mai pagato della prima casa con rivalutazione degli estimi, Questa valanga governativa e padronale può ( grandi profi tti, rendite, patrimoni). -

Out Now! New Edition of the Journal, July 2015.,APPEAL to SUPPORT

Out now! New edition of the Journal, July 2015. Inside this Issue: Namibia: WRP(N) fights for its constitutional rights Namibian miners demand “end evictions!” Programme of the Fourth International: The Theses of Pulacayo (1946) Europe: What next for Greece – and Europe? Bosnia solidarity appeal UK elections APPEAL TO SUPPORT THE RESISTING GREEK PEOPLE and its TRUTH COMMISSION ON PUBLIC DEBT – FOR THE PEOPLES’ RIGHT TO AUDIT PUBLIC DEBT To the people of Europe and the whole world! To all the men and women who reject the politics of austerity and are not willing to pay a public debt which is strangling us and which was agreed to behind our backs and against our interests. We signatories to this appeal stand by the Greek people who, through their vote at the election of 25th January 2015, became the first population in Europe and in the Northern hemisphere to have rejected the politics of austerity imposed to pay an alleged public debt which was negotiated by those on top without the people and against the people. At the same time we consider that the setting up of the Greek Public Debt Truth Commission at the initiative of the president of the Greek Parliament constitutes a historic event, of crucial importance not only for the Greek people but also for the people of Europe and the whole world! Indeed, the Truth Commission of the Greek Parliament, composed of volunteer citizens from across the globe, is destined to be emulated in other countries. First, because the debt problem is a scourge that plagues most of Europe and the world, and -

The Exceptional Position of Migrant Domestic Workers and Care Assistants in Italian Immigration Policy

Bulletin of Italian Politics Vol. 2, No. 2, 2010, 21-38 When Families Need Immigrants: The Exceptional Position of Migrant Domestic Workers and Care Assistants in Italian Immigration Policy Franca van Hooren University of Bremen Abstract: In Italy, immigrants are increasingly employed as domestic workers and care assistants. In elderly care this phenomenon has become so important that we have seen a transformation from a ‘family-,’ to a ‘migrant-in- the-family’ model of care. Though in Italy immigration policies in general have been restrictive, they have, through large immigration quotas and amnesties, mostly supported the entry of domestic workers and care assistants. The expansive policies have been enacted by both centre-left and centre-right governments, even when radical right-wing and strongly anti-immigrant parties have been in government. The exceptional position of domestic workers and care assistants in Italian immigration policies can be explained primarily by the important role these migrants play in the Italian family care system. Family needs seem to overrule anti-immigrant sentiments. Because migrants are employed within the family, care work continues to be informal and irregular. It is often too expensive for families to regularise their domestic workers, while it is unattractive for government strictly to enforce their regularisation. This is problematic because it leaves much room for abuse, putting both families and care workers in highly vulnerable positions. Keywords: immigration policy, elderly care, domestic work, migrant care assistant Each year tens if not hundreds of thousands of people enter Italy to work as domestic workers or care assistants. They are engaged by Italian families to clean the house, to babysit, or to look after an older or disabled family member. -

The Summer University of the Party of the European Left (EL) Will Be One of the First Opportunities for Collective Discussion Since the European Elections

The Summer University of the Party of the European Left (EL) will be one of the first opportunities for collective discussion since the European elections. This will be a discussion that each participant will have developed in his or her own country and organisation, but which can now be brought together for a richer analysis and broader discussion in Fiuggi. The context is a very wide one and so the Summer University will be tasked with: ➔ Taking stock of the crisis of globalisation, the new challenges and new opportunities ahead. The framework of the University is to address both the characteristics of the crisis of globalization and the features of the new movements that are currently developing as its powerful opponents. We will consider the feminist and environmental movements which through their depth of critical thinking and action present the greatest possibility of changing the current political trajectory. ➔ Analysing the crisis of democracy that has occurred over the last thirty years and the specific characteristics of the growth of the fascist right today. ➔ Explaining and deepening our thinking about a new humanism, with a possible dialogue between Marxists and believers, and a discussion on the perspectives of the European left, starting with strengthening the construction of the European Forum. PROGRAMME Wednesday 10 July 2019 19.00 – 20.00 Opening Giovanna Capelli, Communist Refoundation Party, Italy Roberto Morea, transform! europe, Italy Paolo Ferrero, Vice-President of the EL 20.00 Dinner 21.00 Evening International -

From Revolution to Coalition – Radical Left Parties in Europe

e P uro e t Parties in t Parties F e l evolution to Coalition – r al C Birgit Daiber, Cornelia Hildebrandt, Anna Striethorst (Ed.) adi r From From revolution to Coalition – radiCal leFt Parties in euroPe 2 Manuskripte neue Folge 2 r osa luxemburg stiFtung Birgit Daiber, Cornelia Hildebrandt, Anna Striethorst (Ed.) From Revolution to Coalition – Radical Left Parties in Europe Birgit Daiber, Cornelia Hildebrandt, Anna Striethorst (Ed.) From revolution to Coalition – radiCal leFt Parties in euroPe Country studies of 2010 updated through 2011 Phil Hill (Translation) Mark Khan, Eoghan Mc Mahon (Editing) IMPRINT MANUSKRIPTE is published by Rosa-Luxemburg-Foundation ISSN 2194-864X Franz-Mehring-Platz 1 · 10243 Berlin, Germany Phone +49 30 44310-130 · Fax -122 · www.rosalux.de Editorial deadline: June 2012 Layout/typesetting/print: MediaService GmbH Druck und Kommunikation, Berlin 2012 Printed on Circleoffset Premium White, 100 % Recycling Content Editor’s Preface 7 Inger V. Johansen: The Left and Radical Left in Denmark 10 Anna Kontula/Tomi Kuhanen: Rebuilding the Left Alliance – Hoping for a New Beginning 26 Auður Lilja Erlingsdóttir: The Left in Iceland 41 Dag Seierstad: The Left In Norway: Politics in a centre-left government 50 Barbara Steiner: «Communists we are no longer, Social Democrats we can never be the Swedish Left Party» 65 Thomas Kachel: The British Left At The End Of The New Labour Era – An Electoral Analysis 78 Cornelia Hildebrandt: The Left Party in Germany 93 Stéphane Sahuc: Left Parties in France 114 Sascha Wagener: The Left