The Estonian Singing Revolution: Musematic Insights Kaire Maimets 18.11.2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conde, Jonathan (2018) an Examination of Lithuania's Partisan War Versus the Soviet Union and Attempts to Resist Sovietisation

Conde, Jonathan (2018) An Examination of Lithuania’s Partisan War Versus the Soviet Union and Attempts to Resist Sovietisation. Masters thesis, York St John University. Downloaded from: http://ray.yorksj.ac.uk/id/eprint/3522/ Research at York St John (RaY) is an institutional repository. It supports the principles of open access by making the research outputs of the University available in digital form. Copyright of the items stored in RaY reside with the authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full text items free of charge, and may download a copy for private study or non-commercial research. For further reuse terms, see licence terms governing individual outputs. Institutional Repository Policy Statement RaY Research at the University of York St John For more information please contact RaY at [email protected] An Examination of Lithuania’s Partisan War Versus the Soviet Union and Attempts to Resist Sovietisation. Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Research MA History at York St John University School of Humanities, Religion & Philosophy by Jonathan William Conde Student Number: 090002177 April 2018 I confirm that the work submitted is my own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the works of others. This copy has been submitted on the understanding that it is copyright material. Any reuse must comply with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and any licence under which this copy is released. @2018 York St John University and Jonathan William Conde The right of Jonathan William Conde to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 Acknowledgments My gratitude for assisting with this project must go to my wife, her parents, wider family, and friends in Lithuania, and all the people of interest who I interviewed between the autumn of 2014 and winter 2017. -

The Day Holding Hands Changed History Occupation and Annexation of the Baltic States Was Illegal, and Against the Wish of the Respective Nations

The day holding hands changed history occupation and annexation of the Baltic states was illegal, and against the wish of the respective nations. So at 19:00 on 23 August 1989, 50 years after the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was signed, church bells sounded in the Bal- tic states. Mourning ribbons decorated the national flags that had been banned a year before. The participants of the Bal- tic Way were addressed by the leaders of the respective national independence movements: the Estonian Rahvarinne, the Lithuanian Sajūdis, and the Popular Front of Latvia. The following words were chanted – ‘laisvė’, ‘svabadus, ‘brīvība’ (freedom). The symbols of Nazi Germany and the Communist regime of the USSR were burnt on large bonfires. The Baltic states demanded the cessation of the half-century long Soviet occupation, col- onisation, russification and communist genocide. The Baltic Way was a significant step to- wards regaining the national independ- ence of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia, and a source of inspiration for other region- al independence movements. The live chain was also realised in Kishinev by Ro- manians of the Soviet-occupied Bessara- bia or Moldova, while in January 1990, Ukrainians joined hands on the road from Lviv to Kyiv. Just after the Baltic Way campaign, the Berlin Wall fell, the Velvet Revolution in Czechoslovakia began, and the Ceausescu regime in Romania was overthrown. On 23 August 1989, approximately two doomed to be forcedly incorporated into million people stood hand in hand be- the Soviet Union until 1991. The Soviet Un- Recognising the documents of the Baltic tween Tallinn (Estonia), Rīga (Latvia) ion claimed that the Baltic states joined Way as items of documentary heritage of and Vilnius (Lithuania) in one of the voluntarily. -

What You Need to Know If You Are Applying for Estonian Citizenship

WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW IF YOU ARE APPLYING FOR ESTONIAN CITIZENSHIP Published with the support of the Integration and Migration Foundation Our People and the Estonian Ministry of Culture Compiled by Andres Ääremaa, Anzelika Valdre, Toomas Hiio and Dmitri Rõbakov Edited by Kärt Jänes-Kapp Photographs by (p. 5) Office of the President; (p. 6) Koolibri archive; (p. 7) Koolibri archive; (p. 8) Estonian Literary Museum; (p. 9) Koolibri archive, Estonian National Museum; (p. 10) Koolibri archive; (p. 11) Koolibri archive, Estonian Film Archives; (p. 12) Koolibri archive, Wikipedia; (p. 13) Estonian Film Archives / E. Järve, Estonian National Museum; (p. 14) Estonian Film Archives / Verner Puhm, Estonian Film Archives / Harald Lepikson; (p. 15) Estonian Film Archives / Harald Lepikson; (p. 16) Koolibri archive; (p. 17) Koolibri archive; (p. 19) Office of the Minister for Population Affairs / Anastassia Raznotovskaja; (p. 21) Koolibri archive; (p. 22) PM / Scanpix / Ove Maidla; (p. 23) PM / Scanpix / Margus Ansu, Koolibri archive; (p. 24) PM / Scanpix / Mihkel Maripuu; (p. 25) Koolibri archive; (p. 26) PM / Scanpix / Raigo Pajula; (p. 29) Virumaa Teataja / Scanpix / Arvet Mägi; (p. 30) Koolibri archive; (p. 31) Koolibri archive; (p. 32) Koolibri archive; (p. 33) Sakala / Scanpix / Elmo Riig; (p. 24) PM / Scanpix / Mihkel Maripuu; (p. 35) Scanpix / Henn Soodla; (p. 36) PM / Scanpix / Peeter Langovits; (p. 38) PM / Scanpix / Liis Treimann, PM / Scanpix / Toomas Huik, Scanpix / Presshouse / Kalev Lilleorg; (p. 41) PM / Scanpix / Peeter Langovits; (p. 42) Koolibri archive; (p. 44) Sakala / Scanpix / Elmo Riig; (p. 45) Virumaa Teataja / Scanpix / Tairo Lutter; (p. 46) Koolibri archive; (p. 47) Scanpix / Presshouse / Ado Luud; (p. -

Generational Use of News Media in Estonia

Generational Use of News Media in Estonia Contemporary media research highlights the importance of empirically analysing the relationships between media and age; changing user patterns over the life course; and generational experiences within media discourse beyond the widely-hyped buzz terms such as the ‘digital natives’, ‘Google generation’, etc. The Generational Use doctoral thesis seeks to define the ‘repertoires’ of news media that different generations use to obtain topical information and create of News Media their ‘media space’. The thesis contributes to the development of in Estonia a framework within which to analyse generational features in news audiences by putting the main focus on the cultural view of generations. This perspective was first introduced by Karl Mannheim in 1928. Departing from his legacy, generations can be better conceived of as social formations that are built on self- identification, rather than equally distributed cohorts. With the purpose of discussing the emergence of various ‘audiencing’ patterns from the perspectives of age, life course and generational identity, the thesis centres on Estonia – a post-Soviet Baltic state – as an empirical example of a transforming society with a dynamic media landscape that is witnessing the expanding impact of new media and a shift to digitisation, which should have consequences for the process of ‘generationing’. The thesis is based on data from nationally representative cross- section surveys on media use and media attitudes (conducted 2002–2012). In addition to that focus group discussions are used to map similarities and differences between five generation cohorts born 1932–1997 with regard to the access and use of established news media, thematic preferences and spatial orientations of Signe Opermann Signe Opermann media use, and a discursive approach to news formats. -

The First World War Shattered Europe. Austria-Hungary and Russia Disintegrated. a Number of New Nation States Emerged, Including

The First World War shattered Europe. Austria-Hungary and period to work towards national autonomy. Previously belong- onstrations. Trotsky’s hopes were shattered! Secondly German Russia disintegrated. A number of new nation states emerged, ing to several provinces, Estonia now formed one administra- forces were very active in early 1919 in attempting to build including the Republic of Estonia – the smallest and north- tive unit with its own representative body (the Provisional some form of Baltic-German State. Only the battle at Cesis ernmost of the three Baltic countries. Diet of the Province of Estonia) and a government structure. on June 24, 1919 “put an end to these plans” From the end of the Great Northern War (1721) Estonia Estonian became the official language. Estonia was next attacked from the east. On 28 November had belonged to Russia. Within the Russian Empire the tiny In 1917 the power in Russia was seized by the Bolsheviks 1918 the Red Army crossed the Narva River in order to destroy Baltic-German upper class, the real rulers of the Baltic region, who were clearly not interested in the aspirations of the Baltic the Republic of Estonia and forcefully, against the people’s enjoyed various legal and economic privileges. The 19th cen- countries. The Estonian national leadership thus decided to go wishes, incorporate it into the Soviet Union. tury, however, witnessed the so-called national awakening of for full independence. The Republic of Estonia was proclaimed Finland, Sweden, Denmark and Great Britain helped Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania which all then embraced the 20th on 24 February 1918. -

Chicago Open 2018: the Spice Must Flow Edited by Auroni Gupta, Jacob

Chicago Open 2018: The spice must flow Edited by Auroni Gupta, Jacob Reed, Will Holub-Moorman, Jordan Brownstein, Seth Teitler, Eliza Grames, and Joey Goldman, with contributions by Stephen Eltinge, Matt Jackson, JinAh Kim, Raynor Kuang, Dennis Loo, Rohith Nagari, Sriram Pendyala, and Victor Prieto Packet by Food $200 Data $150 Rent $800 Calling it Evanston Open $10,000 Utility $150 someone who is good at the economy please help me budget this. my family is dying (Jason Asher, Brian Kalathiveetil, Matthew Lehmann, John Waldron); and by Art Deko Basilisk (Mike Etzkorn, Adam Fine, Stephen Liu, and Mike Sorice) Tossups 1. One of this man’s houses was the first to be decorated in a painting style typified by white backgrounds and illusionistic architectural frames. He supposedly said “Now I can begin to live like a human being” upon a completion of a palace sporting walls with embedded gems. This man built a palace to connect estates on the Palatine and Esquiline hills that was thus called “Transitoria.” A painter named Fabullus or Famulus crystallized Fourth Style painting while working for this man. Two of this man’s palaces were the first to use extensive barrel vaulting and domes in brick-faced (*) concrete, spurring the “Roman Architectural Revolution.” Raphael’s ceiling for the Stanza della Segnatura was inspired by a visit to this man’s palace. He’s not a Flavian, but the name “Colosseum” comes from the 100-foot bronze statue of himself that this emperor put in front of his palace, the Domus Aurea. For 10 points, name this emperor who rebuilt much of Rome after the 64 AD Great Fire. -

Projections of International Solidarity and Security in Contemporary Estonia

DUKE UNIVERSITY Durham, North Carolina The Spirit Of Survival: Projections of International Solidarity and Security in Contemporary Estonia Katharyn S. Loweth April 2019 Under the supervision of Professor Gareth Price, Department of Linguistics Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for Graduation with Distinction Program in International Comparative Studies Trinity College of Arts and Sciences Table of Contents List of Figures ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................................. 2 Abstract ...................................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................... 4 i. An Overview of the Estonian Nation-State ................................................................................................ 8 ii. Terminology ................................................................................................................................................... 12 iii. Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 17 iv. Overview of the Chapters -

Pop-Jazzmuusika Näidisõppekava

Kohaliku omavalitsuse huvialakooli/muusikakooli üleriigiline pop-jazzmuusika näidisõppekava 2005 1 Sissejuhatus pop-jazzmuusika õppekava juurde Pop-jazzmuusika mõistest Kuni 2003. aastani koondati kõik muusikastiilid väljaspool akadeemilist klassikalist muusikat ühise nimetaja „levimuusika“ alla, mille pakkus välja helilooja ja muusikaajaloolane Valter Ojakäär käibel olnud termini „kerge“ muusika asemel, millele klassikalise muusika puhul vastandati mõiste „tõsine“ muusika. Levimuusikaks loeti nii pop-, rock-, jazz-, folk- kui ka kantri- jt. muusikastiilid. Valter Ojakääru terminid „levi-“ ja „süvamuusika” olid Eestis käibel kuni 2003. aastani, mil seoses jazzialase hariduse küsimuste aktuaalseks muutumisega tuli arutlusele ka „levimuusika“ mõiste. Pop-jazzmuusika õppe- ja ainekavade väljatöötamise koosolekul Saue Muusikakoolis 22. novembril 2003. aastal tõstis töögrupp üles loodava õppekava nimega seonduvad küsimused. Ühine seisukoht oli, et õppesuunale tuleb anda rahvusvaheliselt üheselt mõistetav nimetus. Koosoleku protokollist võib lugeda, et kaaluti mitme variandi vahel: “džäss” (eestikeelne kirjapilt), “jats” (kõnekeelest tulnud ning Eesti Keelekomisjoni poolt põhimõttelise toetuse saanud mugandus), “rütmimuusika” (käibel näit. Taanis), “pop-jazz” (enim kasutuselolev termin maailmas). Küsimus jäi siis veel lahtiseks. Otsus langetati pärast küsitlust eesti jazzmuusikute hulgas ning konsulteerimist Eesti Keelekomisjoniga. 2004. aasta alguses nimetati Viljandi Kultuuriakadeemia ja Tallinna G. Otsa nim. Muusikakooli levimuusika osakonnad -

The Singing Revolution: Chamber Singers in Concert

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData School of Music Programs Music Fall 10-25-2018 The Singing Revolution: Chamber Singers in Concert Mark Grizzard Director Illinois State University Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/somp Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Grizzard, Mark Director, "The Singing Revolution: Chamber Singers in Concert" (2018). School of Music Programs. 3750. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/somp/3750 This Concert Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Music Programs by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Illinois State University College of Fine Arts School of Music I LL I NOl"i SYMl'IIUNV OKl.ll["if'RA 'fl 11 ..ci, .. ilsymphony org Upcoming Events Saturday I October 27 "Ow.a Pdu,h1~" ~hdu:Uc \'nwht Stud1° Rn:n 11 The Singing Revolution: 1030 Jm Kemp Chamber Singers in Concert Pd, \mun \'mn: SstKIKJ lh·cu·1J 2:00 pm Kemp Mark Grizzard, director Scmor Rcs:ual· R u:hd Mdls:r mr~ 1°tmmo 430 pm Kemp Sunday, Ocrobcr 28 GfJJu-uc Rccirnl Uas: Ra l·mr ('lµm1 "T.JOpm Kemp Monday, October 29 JS(J Gunar Fns,-mhk and Encmls 7.30pm Kemp Tuesday, Occobcr JO C:mJ\'oc;atum Breu 11 ll·<K>Jm Kemp Clrndcs \X ' lfokn E·wuhy Reen 11· Fu:uh) Pnon Ouausa 7.30 pm Kemp Wednesday, October l t smnr Qas~ Fn~cmhk KOO pm Kemp Friday, November 2 hzz En;;emhlc I & II K·OOpm CP.1 Kemp Recital Hall Please see the ISU event calendar for more information on the CFA events. -

Soviet Science Fiction Movies in the Mirror of Film Criticism and Viewers’ Opinions

Alexander Fedorov Soviet science fiction movies in the mirror of film criticism and viewers’ opinions Moscow, 2021 Fedorov A.V. Soviet science fiction movies in the mirror of film criticism and viewers’ opinions. Moscow: Information for all, 2021. 162 p. The monograph provides a wide panorama of the opinions of film critics and viewers about Soviet movies of the fantastic genre of different years. For university students, graduate students, teachers, teachers, a wide audience interested in science fiction. Reviewer: Professor M.P. Tselysh. © Alexander Fedorov, 2021. 1 Table of Contents Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 1. Soviet science fiction in the mirror of the opinions of film critics and viewers ………………………… 4 2. "The Mystery of Two Oceans": a novel and its adaptation ………………………………………………….. 117 3. "Amphibian Man": a novel and its adaptation ………………………………………………………………….. 122 3. "Hyperboloid of Engineer Garin": a novel and its adaptation …………………………………………….. 126 4. Soviet science fiction at the turn of the 1950s — 1960s and its American screen transformations……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 130 Conclusion …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….… 136 Filmography (Soviet fiction Sc-Fi films: 1919—1991) ……………………………………………………………. 138 About the author …………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 150 References……………………………………………………………….……………………………………………………….. 155 2 Introduction This monograph attempts to provide a broad panorama of Soviet science fiction films (including television ones) in the mirror of -

Baltic Way 1989 Achieving the Unthinkable - Documentary by Kristine S

Baltic Way 1989 Achieving the Unthinkable - Documentary by Kristine S. At 7pm on August 23, 1989 about 2 million people joined hands forming a human chain spanning 600 kilometres, or almost 400 miles. The inhabitants of the Baltic states, Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia, joined hands in a peaceful protest demanding restoration of their independence. This became known as the Baltic Way. The Baltic Way in 1989, through leadership and non-violent protests, drew global attention to Baltic struggles and contributed to the eventual renewal of the Baltic states’ independence. The Baltic states - Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania - are small countries in Europe on the Baltic Sea. Before World War II, Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia were independent prosperous nations. On 23 August 1939, the Secret Treaty of the Foreign Ministers of the Soviet Union and Germany, known as the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, was signed. It led to the occupation of the Baltic states followed by the war and mass genocide against the Baltic nations. Hundreds of thousands of people, including families with children, were deported to labour camps in Siberia where they were executed, or had to flee their homes never to return. The Baltic nations lived under Soviet rule for 50 years. In the Soviet Union freedom of speech and thought was restricted. The Soviet Union denied the existence of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact for 50 years and insisted that the Baltic states had voluntarily joined the Soviet Union. In the ‘80s people started to gain access to more information. The first protest began in the Baltic states. National movements in each of the Baltic states started to gain wide support of the population. -

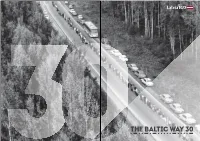

The Baltic Way Towards Freedom

THE BALTIC The Baltic Way WAY 30 Towards Freedom At 19:00 on 23 August 1989 approximately two million people of the Baltic states joined hands forming a live, continuous chain on the road Tallinn-Rīga-Vilnius (660-670 km). Church bells sounded in the Baltic states. Mourning ribbons decorated the national flags that were banned a year ago. The participants of the Baltic Way were addressed by the leaders of Rahvarinne - the Estonian Popular Front, the Lithuanian movement Sajūdis and the Popular Front of Latvia. The following words were heard – ‘laisvė’, ‘svabadus, ‘brīvība’ (freedom). The symbols of Nazi Germany and the Communist regime of the USSR were burned in large bonfires. Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania engaged in collective action against the non-assault agreement between Hitler and Stalin of 23 August 1939 and its secret protocols or the “devil pact”. The Baltic states demanded the cessation of half-century long Soviet occupation, colonisation, russification and Photo 1 (cover photo) communist genocide. The Baltic Way became the The Baltic Way on Pleskava highway. crucial application by the Baltic states’ civil society The photo was taken from the helicopter for independence and return to Europe. It was the on 23 August 1989. first dice in the domino effect that disrupted the Photographer Aivars Liepiņš. Archive of the Latvian Institute. totalitarian regime in Eastern Europe - the first step towards regaining national independence of Latvia. © State Chancellery of Latvia, 2019 THE BALTIC WAY 30 1 2 THE BALTIC WAY 30 Photo 2 Causes and Participants of the Baltic Way on the Stone Bridge (at that time the October Bridge).