Estonia “Has No Time”: Existential Politics at the End of Empire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

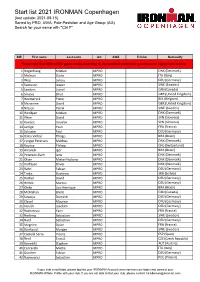

Start List 2021 IRONMAN Copenhagen (Last Update: 2021-08-15) Sorted by PRO, AWA, Pole Posistion and Age Group (AG) Search for Your Name with "Ctrl F"

Start list 2021 IRONMAN Copenhagen (last update: 2021-08-15) Sorted by PRO, AWA, Pole Posistion and Age Group (AG) Search for your name with "Ctrl F" BIB First name Last name AG AWA TriClub Nationallty Please note that BIBs will be given onsite according to the selected swim time you choose in registration oniste. 1 Hogenhaug Kristian MPRO DNK (Denmark) 2 Molinari Giulio MPRO ITA (Italy) 3 Wojt Lukasz MPRO DEU (Germany) 4 Svensson Jesper MPRO SWE (Sweden) 5 Sanders Lionel MPRO CAN (Canada) 6 Smales Elliot MPRO GBR (United Kingdom) 7 Heemeryck Pieter MPRO BEL (Belgium) 8 Mcnamee David MPRO GBR (United Kingdom) 9 Nilsson Patrik MPRO SWE (Sweden) 10 Hindkjær Kristian MPRO DNK (Denmark) 11 Plese David MPRO SVN (Slovenia) 12 Kovacic Jaroslav MPRO SVN (Slovenia) 14 Jarrige Yvan MPRO FRA (France) 15 Schuster Paul MPRO DEU (Germany) 16 Dário Vinhal Thiago MPRO BRA (Brazil) 17 Lyngsø Petersen Mathias MPRO DNK (Denmark) 18 Koutny Philipp MPRO CHE (Switzerland) 19 Amorelli Igor MPRO BRA (Brazil) 20 Petersen-Bach Jens MPRO DNK (Denmark) 21 Olsen Mikkel Hojborg MPRO DNK (Denmark) 22 Korfitsen Oliver MPRO DNK (Denmark) 23 Rahn Fabian MPRO DEU (Germany) 24 Trakic Strahinja MPRO SRB (Serbia) 25 Rother David MPRO DEU (Germany) 26 Herbst Marcus MPRO DEU (Germany) 27 Ohde Luis Henrique MPRO BRA (Brazil) 28 McMahon Brent MPRO CAN (Canada) 29 Sowieja Dominik MPRO DEU (Germany) 30 Clavel Maurice MPRO DEU (Germany) 31 Krauth Joachim MPRO DEU (Germany) 32 Rocheteau Yann MPRO FRA (France) 33 Norberg Sebastian MPRO SWE (Sweden) 34 Neef Sebastian MPRO DEU (Germany) 35 Magnien Dylan MPRO FRA (France) 36 Björkqvist Morgan MPRO SWE (Sweden) 37 Castellà Serra Vicenç MPRO ESP (Spain) 38 Řenč Tomáš MPRO CZE (Czech Republic) 39 Benedikt Stephen MPRO AUT (Austria) 40 Ceccarelli Mattia MPRO ITA (Italy) 41 Günther Fabian MPRO DEU (Germany) 42 Najmowicz Sebastian MPRO POL (Poland) If your club is not listed, please log into your IRONMAN Account (www.ironman.com/login) and connect your IRONMAN Athlete Profile with your club. -

Country Background Report Estonia

OECD Review of Policies to Improve the Effectiveness of Resource Use in Schools Country Background Report Estonia This report was prepared by the Ministry of Education and Research of the Republic of Estonia, as an input to the OECD Review of Policies to Improve the Effectiveness of Resource Use in Schools (School Resources Review). The participation of the Republic of Estonia in the project was organised with the support of the European Commission (EC) in the context of the partnership established between the OECD and the EC. The partnership partly covered participation costs of countries which are part of the European Union’s Erasmus+ programme. The document was prepared in response to guidelines the OECD provided to all countries. The opinions expressed are not those of the OECD or its Member countries. Further information about the OECD Review is available at www.oecd.org/edu/school/schoolresourcesreview.htm Ministry of Education and Research, 2015 Table of Content Table of Content ....................................................................................................................................................2 List of acronyms ....................................................................................................................................................7 Executive summary ...............................................................................................................................................9 Introduction .........................................................................................................................................................10 -

Download Download

Ajalooline Ajakiri, 2016, 3/4 (157/158), 477–511 Historical consciousness, personal life experiences and the orientation of Estonian foreign policy toward the West, 1988–1991 Kaarel Piirimäe and Pertti Grönholm ABSTRACT The years 1988 to 1991 were a critical juncture in the history of Estonia. Crucial steps were taken during this time to assure that Estonian foreign policy would not be directed toward the East but primarily toward the integration with the West. In times of uncertainty and institutional flux, strong individuals with ideational power matter the most. This article examines the influence of For- eign Minister Lennart Meri’s and Prime Minister Edgar Savisaar’s experienc- es and historical consciousness on their visions of Estonia’s future position in international affairs. Life stories help understand differences in their horizons of expectation, and their choices in conducting Estonian diplomacy. Keywords: historical imagination, critical junctures, foreign policy analysis, So- viet Union, Baltic states, Lennart Meri Much has been written about the Baltic states’ success in breaking away from Eastern Europe after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, and their decisive “return to the West”1 via radical economic, social and politi- Research for this article was supported by the “Reimagining Futures in the European North at the End of the Cold War” project which was financed by the Academy of Finland. Funding was also obtained from the “Estonia, the Baltic states and the Collapse of the Soviet Union: New Perspectives on the End of the Cold War” project, financed by the Estonian Research Council, and the “Myths, Cultural Tools and Functions – Historical Narratives in Constructing and Consolidating National Identity in 20th and 21st Century Estonia” project, which was financed by the Turku Institute for Advanced Studies (TIAS, University of Turku). -

Legacy Image

5-(948-~gblb SOWARE ENGINEERING LABORATORY SERIES SEL-95-004 PROCEEDINGS OF THE TWENTIETH ANNUAL SOFTWARE ENGINEERING WORKSHOP DECEMBER 1995 National Aeronautics and Space Administration Goddard Space Flight Center Greenbelt, Maryland 20771 Proceedings of the Twentieth Annual Software Engineering Workshop November 29-30,1995 GODDARD SPACE FLIGHT CENTER Greenbelt, Maryland The Software Engineering Laboratory (SEL) is an organization sponsored by the National Aeronautics and Space AdministratiodGoddard Space Flight Center (NASAIGSFC) and created to investigate the effectiveness of software engineering technologies when applied to the development of applications software. The SEL was created in 1976 and has three primary organizational members: NASAIGSFC, Software Engineering Branch The University of Maryland, Department of Computer Science .I Computer Sciences Corporation, Software Engineering Operation The goals of the SEL are (1) to understand the software development process in the GSFC environment; (2) to measure the effects of various methodologies, tools, and models on this process; and (3) to identifjr and then to apply successful development practices. The activities, findings, and recommendations of the SEL are recorded in the Software Engineering Laboratory Series, a continuing series of reports that includes this document. Documents from the Software Engineering Laboratory Series can be obtained via the SEL homepage at: or by writing to: Software Engineering Branch Code 552 Goddard Space Flight Center Greenbelt, Maryland 2077 1 SEW Proceedings iii The views and findings expressed herein are those of, the authors and presenters and do not necessarily represent the views, estimates, or policies of the SEL. All material herein is reprinted as submitted by authors and presenters, who are solely responsible for compliance with any relevant copyright, patent, or other proprietary restrictions. -

Presentation Kit

15YEARS PRESENTATION KIT TURKISH POLICY QUARTERLY PRESENTATION KIT MARCH 2017 QUARTERLY Table of Contents What is TPQ? ..............................................................................................................4 TPQ’s Board of Advisors ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������5 Strong Outreach ........................................................................................................ 7 Online Blog and Debate Sections ..........................................................................8 TPQ Events ...............................................................................................................10 TPQ in the Media ..................................................................................................... 11 Support TPQ .............................................................................................................14 Premium Sponsorship ............................................................................................ 15 Print Advertising .......................................................................................................18 Premium Sponsor ...................................................................................................19 Advertiser ................................................................................................................. 20 Online Advertising ................................................................................................... 21 -

List of Prime Ministers of Estonia

SNo Name Took office Left office Political party 1 Konstantin Päts 24-02 1918 26-11 1918 Rural League 2 Konstantin Päts 26-11 1918 08-05 1919 Rural League 3 Otto August Strandman 08-05 1919 18-11 1919 Estonian Labour Party 4 Jaan Tõnisson 18-11 1919 28-07 1920 Estonian People's Party 5 Ado Birk 28-07 1920 30-07 1920 Estonian People's Party 6 Jaan Tõnisson 30-07 1920 26-10 1920 Estonian People's Party 7 Ants Piip 26-10 1920 25-01 1921 Estonian Labour Party 8 Konstantin Päts 25-01 1921 21-11 1922 Farmers' Assemblies 9 Juhan Kukk 21-11 1922 02-08 1923 Estonian Labour Party 10 Konstantin Päts 02-08 1923 26-03 1924 Farmers' Assemblies 11 Friedrich Karl Akel 26-03 1924 16-12 1924 Christian People's Party 12 Jüri Jaakson 16-12 1924 15-12 1925 Estonian People's Party 13 Jaan Teemant 15-12 1925 23-07 1926 Farmers' Assemblies 14 Jaan Teemant 23-07 1926 04-03 1927 Farmers' Assemblies 15 Jaan Teemant 04-03 1927 09-12 1927 Farmers' Assemblies 16 Jaan Tõnisson 09-12 1927 04-121928 Estonian People's Party 17 August Rei 04-121928 09-07 1929 Estonian Socialist Workers' Party 18 Otto August Strandman 09-07 1929 12-02 1931 Estonian Labour Party 19 Konstantin Päts 12-02 1931 19-02 1932 Farmers' Assemblies 20 Jaan Teemant 19-02 1932 19-07 1932 Farmers' Assemblies 21 Karl August Einbund 19-07 1932 01-11 1932 Union of Settlers and Smallholders 22 Konstantin Päts 01-11 1932 18-05 1933 Union of Settlers and Smallholders 23 Jaan Tõnisson 18-05 1933 21-10 1933 National Centre Party 24 Konstantin Päts 21-10 1933 24-01 1934 Non-party 25 Konstantin Päts 24-01 1934 -

Challenges Facing Estonian Economy in the European Union

Vahur Kraft: Challenges facing Estonian economy in the European Union Speech by Mr Vahur Kraft, Governor of the Bank of Estonia, at the Roundtable “Has social market economy a future?”, organised by the Konrad Adenauer Foundation, Tallinn, 19 August 2002. * * * A. Introduction, review of the early 1990s and comparison with the present day First of all, allow me to thank Konrad Adenauer Foundation for the organisation of this interesting roundtable and for the honourable invitation to speak about “Challenges of Estonian economy in the European Union”. Today’s event shows yet again how serious is the respected organisers’ interest towards the EU applicant countries. I personally appreciate highly your support to our reforms and convergence in the society and economy. From the outside it may seem that the transformation and convergence process in Estonia has been easy and smooth, but against this background there still exist numerous hidden problems. One should not forget that for two generations half of Europe was deprived of civil society, private ownership, market economy. This is truth and it has to be reckoned with. It is also clear that the reflections of the “shadows of the past” can still be observed. They are of different kind. If people want the state to ensure their well-being but are reluctant to take themselves any responsibility for their own future, it is the effect of the shadows of the past. If people are reluctant to pay taxes but demand social security and good roads, it is the shadow of the past. In brief, if people do not understand why elections are held and what is the state’s role, it is the shadow of the past. -

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title The baltic states: Years of dependence, 1980–1986 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7885d375 Journal Journal of Baltic Studies, 20(1) ISSN 0162-9778 Authors Misiunas, RJ Taagepera, R Publication Date 1989-03-01 DOI 10.1080/01629778800000291 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California THE BALTIC STATES: YEARS OF DEPENDENCE, 1980-1986 Romuald J. Misiunas, Yale University Rein Taagepera, University of California, Irvine In 1983 we published a book entitled The Baltic States: Years of Depen- dence 1940-1980. ~ The present article represents an update chapter which re- views the years 1980-1986. Compared to the late 1970s and the early 1980s, a period of stagnation, 1987 was a singularly difficult time for writing recent Soviet and Baltic history. CPSU General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev was trying to overcome the general stagnation in which the Soviet Union found itself, and the outcome of his increasingly dramatic effort remains uncertain. Hence, the historical perspective for our interpretation of recent events is missing. Will economic and techno- logical growth in the USSR be achieved without appreciable political changes, or will liberalization be the price for technological progress? If liberalization is needed, will Gorbachev be able to pay the price, or will he maintain the past mix of authoritarian and totalitarian features even at the cost of continued economic stagnation? If Gorbachev chooses liberalization, will more conservative bureau- cratic forces eventually topple him? If the Soviet leadership opts for continued economic stagnation, will the Soviet population continue to be submissive indefinitely? As before, Baltic history in the 1980s continues to depend on the interplay of local aspirations with decisions made in Moscow. -

Culture and Sports

2003 PILK PEEGLISSE • GLANCE AT THE MIRROR Kultuur ja sport Culture and Sports IMEPÄRANE EESTI MUUSIKA AMAZING ESTONIAN MUSIC Millist imepärast mõju avaldab soome-ugri What marvellous influence does the Finno-Ugric keelkond selle kõnelejate muusikaandele? language family have on the musical talent of Selles väikeses perekonnas on märkimisväär- their speakers? In this small family, Hungarians seid saavutusi juba ungarlastel ja soomlastel. and Finns have already made significant achieve- Ka mikroskoopilise Eesti muusikaline produk- ments. Also the microscopic Estonia stuns with its tiivsus on lausa harukordne. musical productivity. Erkki-Sven Tüür on vaid üks neist Tallinnast Erkki-Sven Tüür is only one of those voices coming tulevatest häältest, kellest kõige kuulsamaks from Tallinn, the most famous of whom is regarded võib pidada Arvo Pärti. Dirigent, kes Tüüri to be Arvo Pärt. The conductor of the Birmingham symphony orchestra who performed on Tüür's plaadil "Exodus" juhatab Birminghami süm- record "Exodus" is his compatriot Paavo Järvi, fooniaorkestrit, on nende kaasmaalane Paavo regarded as one of the most promising conductors. Järvi, keda peetakse üheks paljulubavamaks (Libération, 17.10) dirigendiks. (Libération, 17.10) "People often talk about us as being calm and cold. "Meist räägitakse tavaliselt, et oleme rahulik ja This is not so. There is just a different kind of fire külm rahvas. See ei vasta tõele. Meis põleb teist- burning in us," decleares Paavo Järvi, the new sugune tuli," ütles Bremeni Kammerfilharmoo- conductor of the Bremen Chamber Philharmonic. nia uus dirigent Paavo Järvi. Tõepoolest, Paavo Indeed, Paavo Järvi charmed the audience with Järvi võlus publikut ettevaatlike käeliigutuste, careful hand gestures, mimic sprinkled with winks silmapilgutusterohke miimika ja hiljem temaga and with a dry sense of humour, which became vesteldes avaldunud kuiva huumoriga. -

University of Birmingham Chronology

University of Birmingham Chronology Galpin, Charlotte DOI: 10.1111/jcms.12588 License: None: All rights reserved Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Galpin, C 2017, 'Chronology: The European Union in 2016', Journal of Common Market Studies. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12588 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: Eligibility for repository: Checked on 28/7/2017 General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. When citing, please reference the published version. Take down policy While the University of Birmingham exercises care and attention in making items available there are rare occasions when an item has been uploaded in error or has been deemed to be commercially or otherwise sensitive. -

The Res Publica Party in Estonia

Meteoric Trajectory: The Res Publica Party in Estonia REIN TAAGEPERA Formed in 2001, Res Publica won the Estonian parliamentary elections in 2003, and its leader became prime minister. It failed to win a single seat in the European Parliament in 2004 and was down to 5 per cent in opinion polls in 2005 when it dropped out of the cabinet. The founding chairperson of the party analyses here the causes for Res Publica’s rapid rise and fall, reviewing the socio-political background and drawing comparisons with other new parties in Europe. Res Publica was a genuinely new party that involved no previous major players. It might be charac- terized as a ‘purifying bridge party’ that filled an empty niche at centre right. Its rise was among the fastest in Europe. For success of a new party, each of three factors must be present to an appreciable degree: Prospect of success ¼ Members  Money  Visibility. Res Publica had all three, but rapid success spoiled the party leadership. Their governing style became arrogant and they veered to the right, alienating their centrist core constituency. It no longer mattered for the quality of Estonian politics whether Res Publica faded or survived. Key words: new parties; Estonia; Res Publica; rightist politics Democratization includes developing a workable party system. Around 2000, I would have told anyone who cared to listen that Estonia had too many parties. A study by Grofman, Mikkel and Taagepera1 also noted that no major new player had entered the field since 1995. We characterized the party constellation in the early 1990s as kaleidoscopic, but gave figures to show that the party system in Estonia seemed to stabilize. -

What You Need to Know If You Are Applying for Estonian Citizenship

WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW IF YOU ARE APPLYING FOR ESTONIAN CITIZENSHIP Published with the support of the Integration and Migration Foundation Our People and the Estonian Ministry of Culture Compiled by Andres Ääremaa, Anzelika Valdre, Toomas Hiio and Dmitri Rõbakov Edited by Kärt Jänes-Kapp Photographs by (p. 5) Office of the President; (p. 6) Koolibri archive; (p. 7) Koolibri archive; (p. 8) Estonian Literary Museum; (p. 9) Koolibri archive, Estonian National Museum; (p. 10) Koolibri archive; (p. 11) Koolibri archive, Estonian Film Archives; (p. 12) Koolibri archive, Wikipedia; (p. 13) Estonian Film Archives / E. Järve, Estonian National Museum; (p. 14) Estonian Film Archives / Verner Puhm, Estonian Film Archives / Harald Lepikson; (p. 15) Estonian Film Archives / Harald Lepikson; (p. 16) Koolibri archive; (p. 17) Koolibri archive; (p. 19) Office of the Minister for Population Affairs / Anastassia Raznotovskaja; (p. 21) Koolibri archive; (p. 22) PM / Scanpix / Ove Maidla; (p. 23) PM / Scanpix / Margus Ansu, Koolibri archive; (p. 24) PM / Scanpix / Mihkel Maripuu; (p. 25) Koolibri archive; (p. 26) PM / Scanpix / Raigo Pajula; (p. 29) Virumaa Teataja / Scanpix / Arvet Mägi; (p. 30) Koolibri archive; (p. 31) Koolibri archive; (p. 32) Koolibri archive; (p. 33) Sakala / Scanpix / Elmo Riig; (p. 24) PM / Scanpix / Mihkel Maripuu; (p. 35) Scanpix / Henn Soodla; (p. 36) PM / Scanpix / Peeter Langovits; (p. 38) PM / Scanpix / Liis Treimann, PM / Scanpix / Toomas Huik, Scanpix / Presshouse / Kalev Lilleorg; (p. 41) PM / Scanpix / Peeter Langovits; (p. 42) Koolibri archive; (p. 44) Sakala / Scanpix / Elmo Riig; (p. 45) Virumaa Teataja / Scanpix / Tairo Lutter; (p. 46) Koolibri archive; (p. 47) Scanpix / Presshouse / Ado Luud; (p.