Rein Taagepera, University of California, Irvine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Download

Ajalooline Ajakiri, 2016, 3/4 (157/158), 477–511 Historical consciousness, personal life experiences and the orientation of Estonian foreign policy toward the West, 1988–1991 Kaarel Piirimäe and Pertti Grönholm ABSTRACT The years 1988 to 1991 were a critical juncture in the history of Estonia. Crucial steps were taken during this time to assure that Estonian foreign policy would not be directed toward the East but primarily toward the integration with the West. In times of uncertainty and institutional flux, strong individuals with ideational power matter the most. This article examines the influence of For- eign Minister Lennart Meri’s and Prime Minister Edgar Savisaar’s experienc- es and historical consciousness on their visions of Estonia’s future position in international affairs. Life stories help understand differences in their horizons of expectation, and their choices in conducting Estonian diplomacy. Keywords: historical imagination, critical junctures, foreign policy analysis, So- viet Union, Baltic states, Lennart Meri Much has been written about the Baltic states’ success in breaking away from Eastern Europe after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, and their decisive “return to the West”1 via radical economic, social and politi- Research for this article was supported by the “Reimagining Futures in the European North at the End of the Cold War” project which was financed by the Academy of Finland. Funding was also obtained from the “Estonia, the Baltic states and the Collapse of the Soviet Union: New Perspectives on the End of the Cold War” project, financed by the Estonian Research Council, and the “Myths, Cultural Tools and Functions – Historical Narratives in Constructing and Consolidating National Identity in 20th and 21st Century Estonia” project, which was financed by the Turku Institute for Advanced Studies (TIAS, University of Turku). -

Preoccupied by the Past

© Scandia 2010 http://www.tidskriftenscandia.se/ Preoccupied by the Past The Case of Estonian’s Museum of Occupations Stuart Burch & Ulf Zander The nation is born out of the resistance, ideally without external aid, of its nascent citizens against oppression […] An effective founding struggle should contain memorable massacres, atrocities, assassina- tions and the like, which serve to unite and strengthen resistance and render the resulting victory the more justified and the more fulfilling. They also can provide a focus for a ”remember the x atrocity” histori- cal narrative.1 That a ”foundation struggle mythology” can form a compelling element of national identity is eminently illustrated by the case of Estonia. Its path to independence in 98 followed by German and Soviet occupation in the Second World War and subsequent incorporation into the Soviet Union is officially presented as a period of continuous struggle, culminating in the resumption of autonomy in 99. A key institution for narrating Estonia’s particular ”foundation struggle mythology” is the Museum of Occupations – the subject of our article – which opened in Tallinn in 2003. It conforms to an observation made by Rhiannon Mason concerning the nature of national museums. These entities, she argues, play an important role in articulating, challenging and responding to public perceptions of a nation’s histories, identities, cultures and politics. At the same time, national museums are themselves shaped by the nations within which they are located.2 The privileged role of the museum plus the potency of a ”foundation struggle mythology” accounts for the rise of museums of occupation in Estonia and other Eastern European states since 989. -

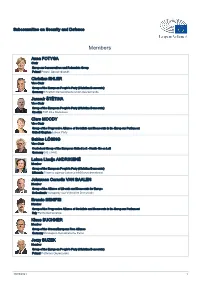

List of Members

Subcommittee on Security and Defence Members Anna FOTYGA Chair European Conservatives and Reformists Group Poland Prawo i Sprawiedliwość Christian EHLER Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Germany Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands Jaromír ŠTĚTINA Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Czechia TOP 09 a Starostové Clare MOODY Vice-Chair Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament United Kingdom Labour Party Sabine LÖSING Vice-Chair Confederal Group of the European United Left - Nordic Green Left Germany DIE LINKE. Laima Liucija ANDRIKIENĖ Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Lithuania Tėvynės sąjunga-Lietuvos krikščionys demokratai Johannes Cornelis VAN BAALEN Member Group of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Netherlands Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie Brando BENIFEI Member Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament Italy Partito Democratico Klaus BUCHNER Member Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance Germany Ökologisch-Demokratische Partei Jerzy BUZEK Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Poland Platforma Obywatelska 30/09/2021 1 Aymeric CHAUPRADE Member Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy Group France Les Français Libres Javier COUSO PERMUY Member Confederal Group of the European United Left - Nordic Green Left Spain Independiente Arnaud DANJEAN Member Group of the European People's Party -

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title The baltic states: Years of dependence, 1980–1986 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7885d375 Journal Journal of Baltic Studies, 20(1) ISSN 0162-9778 Authors Misiunas, RJ Taagepera, R Publication Date 1989-03-01 DOI 10.1080/01629778800000291 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California THE BALTIC STATES: YEARS OF DEPENDENCE, 1980-1986 Romuald J. Misiunas, Yale University Rein Taagepera, University of California, Irvine In 1983 we published a book entitled The Baltic States: Years of Depen- dence 1940-1980. ~ The present article represents an update chapter which re- views the years 1980-1986. Compared to the late 1970s and the early 1980s, a period of stagnation, 1987 was a singularly difficult time for writing recent Soviet and Baltic history. CPSU General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev was trying to overcome the general stagnation in which the Soviet Union found itself, and the outcome of his increasingly dramatic effort remains uncertain. Hence, the historical perspective for our interpretation of recent events is missing. Will economic and techno- logical growth in the USSR be achieved without appreciable political changes, or will liberalization be the price for technological progress? If liberalization is needed, will Gorbachev be able to pay the price, or will he maintain the past mix of authoritarian and totalitarian features even at the cost of continued economic stagnation? If Gorbachev chooses liberalization, will more conservative bureau- cratic forces eventually topple him? If the Soviet leadership opts for continued economic stagnation, will the Soviet population continue to be submissive indefinitely? As before, Baltic history in the 1980s continues to depend on the interplay of local aspirations with decisions made in Moscow. -

Politics, Migration and Minorities in Independent and Soviet Estonia, 1918-1998

Universität Osnabrück Fachbereich Kultur- und Geowissenschaften Fach Geschichte Politics, Migration and Minorities in Independent and Soviet Estonia, 1918-1998 Dissertation im Fach Geschichte zur Erlangung des Grades Dr. phil. vorgelegt von Andreas Demuth Graduiertenkolleg Migration im modernen Europa Institut für Migrationsforschung und Interkulturelle Studien (IMIS) Neuer Graben 19-21 49069 Osnabrück Betreuer: Prof. Dr. Klaus J. Bade, Osnabrück Prof. Dr. Gerhard Simon, Köln Juli 2000 ANDREAS DEMUTH ii POLITICS, MIGRATION AND MINORITIES IN ESTONIA, 1918-1998 iii Table of Contents Preface...............................................................................................................................................................vi Abbreviations...................................................................................................................................................vii ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................ VII 1 INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................3 1.1 CONCEPTUAL AND METHODOLOGICAL ISSUES ...............................................4 1.1.1 Conceptualising Migration ..................................................................5 1.1.1.1 Socio-Historical Migration Research....................................................................................5 1.1.1.2 A Model of Migration..........................................................................................................6 -

Eesti Rahvusliku Sõltumatuse Partei

Eesti Rahvusliku Sõltumatuse Partei ERSP aeg MTÜ Magna Memoria 2008 g Sisukord Vabariigi President Toomas Hendrik Ilves. Eessõna ... 12 Tunne Kelam. ERSP - 20 aastat ... 16 Jaan Tammsalu. ERSP ja vaimulikud ... 21 Mati Kiirend. ERSP - demokraatlike liikumiste järjepidevuse kandja ... 24 Jüri Adams. ERSP arenguetapid ... 40 Lagle Parek. Stalinismiohvrite mälestusmärk ... 56 Valev Kruusa/u kõne Hirvepargi miitingul23.08.1988 ..62 Vello Salum. Kommunismiohvrite memoriaal Pilistveres ... 64 Lagle Parek. Koos ja eraldi kurjuse impeeriumi lammutamas ... 69 Mari-Ann Kelam. Eesti pagulaskonna vabadusvõitlus ja ERSP ... 96 Linnart Mäll. Esindamata Rahvaste Organisatsioon ... 110 Jüri Adams. ERSP ja põhiseadus ... 114 Andres Mäe. ERSP ja valimised ... 130 Viktor Niitsoo. Miks ERSP ei kestnud? ... 144 Eve Pärnaste. ERSP TORMILINE ALGUS. Kronoloogia Eellood: 1987 ... 154 1988... 160 21. jaanuar. Ettepanek Eesti Rahvusliku Sõltumatuse Partei loomiseks ... 165 2.veebruar ... 169 24. veebruari meeleavaldused ... 183 25. märtsi meeleavaldused ... 199 21. aprill. ERSP Korraldava Toimkonna moodustamine ... 210 l.mai ... 212 11. mai. ERSP Korraldava Toimkonna dokumendid: . Avalik kiri ENSV Ülemnõukogu Presiidiumile ... 2.18 . Üleskutse ENSV Ülemnõukogule, ENSV Ministrite Nõukogule, ENSV Prokuratuurile, ENSV Justiitsministeeriumile ... 220 Abipalve rahvusvahelistele abistamisorganisatsioonidele ... 221 Sisukord 4. juuni. Eesti I Sõltumatu Noortefoorum. ERSP sõnavõtud: Eve Pärnaste ... 229 Arvo Pesti ... 231 Andres Mäe ... 233 14.juuni miitingud ... 235 1. -

Integrating the Central European Past Into a Common Narrative: the Mobilizations Around the ’Crimes of Communism’ in the European Parliament Laure Neumayer

Integrating the Central European Past into a Common Narrative: the mobilizations around the ’crimes of Communism’ in the European Parliament Laure Neumayer To cite this version: Laure Neumayer. Integrating the Central European Past into a Common Narrative: the mobiliza- tions around the ’crimes of Communism’ in the European Parliament. Journal of Contemporary European Studies, Taylor & Francis (Routledge), 2015, Transnational Memory Politics in Europe: Interdisciplinary Approaches 23 (3), pp.344-363. 10.1080/14782804.2014.1001825. hal-01355450 HAL Id: hal-01355450 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01355450 Submitted on 23 Aug 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Integrating the Central European Past into a Common Narrative: the mobilizations around the ‘crimes of Communism’ in the European Parliament LAURE NEUMAYER Université Paris 1 Panthéon Sorbonne and Institut Universitaire de France, France ABSTRACT: After the Cold War, a new constellation of actors entered transnational European assemblies. Their interpretation of European history, which was based on the equivalence of the two ‘totalitarianisms’, Stalinism and Nazism, directly challenged the prevailing Western European narrative constructed on the uniqueness of the Holocaust as the epitome of evil. -

14426 Hon. Paul E. Kanjorski Hon. Ike Skelton

14426 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS, Vol. 152, Pt. 11 July 13, 2006 Vladimir Bukovsky—Cambridge Univer- Michael McFaul—Stanford University, US; intendent of the Wyoming Valley West School sity, UK; Alan Mendoza—Executive Director, Henry District. Leos Carax—Film director, France; Jackson; Society, UK; Mr. Piazza received his Bachelor of Science Patrice Che´reau—Film and theater direc- Marianne Mikko—Member, European Par- tor, France; liament, Estonia; degree from Mansfield University and his Mas- Daniel Cohn-Bendit—Member, European; Tim Montgomerie—Editor, ter of Science degree from Wilkes University. Parliament, Germany; ConservativeHome.com; His post-graduate work includes principal cer- Pierre Daix—Writer, France; Martin Palousˇ—Permanent Czech Repub- tification and a superintendent’s letter of eligi- Prof. Nicholas Daniloff—Northeastern Uni- lic; Representative to the United Nations; bility from Temple University. versity, US; former Czech Ambassador to the US; Mr. Piazza began his career with Wyoming Ruth Daniloff—Writer, US; Carlo di Pamparato—Children of Chechnya Valley West School District in 1971. Over the Fertilio Dario—Comitatus libertates; Action; Relief Mission (CCHARM), UK; past 35 years, Mr. Piazza has taught elemen- Franco Debennedetti—Senator, Italy; Richard Pipes—Harvard University, US; Martin Dewhirst—University of Glasgow, Daniel Pipes—Writer, US; tary grades ranging from kindergarten through Scotland; Daniel Pletka—American Enterprise Insti- sixth grade in subject areas including mathe- Freimut Duve—Former member of the Ger- tute (AEI), US; matics, social studies and reading. man Bundestag; Organisation for Security Oksana Ragazzi—UK; He was an instructional support specialist, and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) Rep- Josep Ramoneda—Philosopher, Center of head teacher and department chairperson. -

Overview Print Page Close Window

World Directory of Minorities Europe MRG Directory –> Moldova –> Moldova Overview Print Page Close Window Moldova Overview Environment Peoples History Governance Current state of minorities and indigenous peoples Environment The Republic of Moldova, formerly the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic, is situated between Ukraine to the north, east and south, and Romania to the west. Since independence in 1991 the country has faced a secessionist challenge in its eastern region, Transnistria (also known as Transdniestria or the ‘Predniestrovian Moldovan Republic'), lying on the eastern side of the Dniester river. Peoples Main languages: Moldovan/Romanian, Russian. Main religions: Eastern Orthodox Christianity. According to the 2004 census, main minority groups include Ukrainians (8.4%), Russians (5.9%), Gagauz (4.4%), Romanians (2.2%) and Bulgarians (1.9%). History At the heart of contemporary minority problems are the different relationships that developed between Moldova's ethnic groups under the various empires that have controlled the region - the Ottoman Empire, the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union. The legacy of external control for Moldova is a society arranged around a complex series of loosely interconnected socioeconomic, political and ethno- territorial subsystems often organized on the basis of divergent sets of interests. Of central importance is the different imperial history experienced by the peoples living in the Moldovan territories east of the Dniester river and those to the west. Prior to the collapse of the Soviet Union, the left bank of the Dniester river had enjoyed almost uninterrupted links to Moscow for nearly 200 years and the region had only intermittently experienced Romanian rule. In 1791 (Treaty of Jassy), the eastern lands were absorbed into the Russian Empire. -

THE BALTIC CHAIN: a STUDY of the ORGANISATION FACETS of LARGE-SCALE PROTEST from a MICRO-LEVEL PERSPECTIVE Paula Christie

LITHUANIAN HISTORICAL STUDIES 20 2015 ISSN 1392-2343 PP. 183–211 THE BALTIC CHAIN: A STUDY OF THE ORGANISATION FACETS OF LARGE-SCALE PROTEST FROM A MICRO-LEVEL PERSPECTIVE Paula Christie ABSTRACT Following the introduction of Gorbachev’s policy of glasnost, details of the secret protocols contained within the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 1939 were subsequently published. This led to widespread condemnation of the Soviet annexation of the three Baltic countries, which culminated in one of the largest-ever human chain protests. How was a protest spanning 671 kilometres and involving almost two million people across Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia organised and coordinated? Did particular variables impact upon individual levels of participant engagement and experience? This article engages with the experiences of those who were involved in the protest at a grass-roots level, and provides a nuanced picture of participant engagement often lacking within the dominant commemorative narrative of the protest. Introduction The Baltic countries of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia were sur- rendered to Soviet influence under the secret protocols contained within the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 1939, drawn up between Nazi Germany and the USSR. 1 The annexation of the three Baltic countries was not internationally recognised, and in the wake of Gorbachev’s policy of glasnost, the publication of the protocols in 1988 sparked a number of large-scale nationalist protests calling for national sovereignty to be restored. 2 On 23 August 1989 these nationalist protests culminated in the formation of an unbroken human chain made up of approximately two million men, women and children, from Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia, which stretched 1 R.J. -

Uncaptive Minds

Uncaptive Minds Special Issue: 25 Years After 1989 Reflections on Unfinished Revolutions Summer 2015 UNCAPTIVE MINDS SPECIAL ISSUE • 25 YEARS AFTER 1989 REFLECTIONS ON UNFINISHED REVOLUTIONS ISSN: 0897–9669 EDITORS: ERIC CHENOWETH AND IRENA LASOTA Cover Design by Małgorzata Flis © Copyright 2015 by the Institute for Democracy in Eastern Europe. This Special Issue of Uncaptive Minds is being published as part of the seminar project, “25 Years After 1989: Time for Reflection on Unfinished Business.” The Special Issue includes the full edited papers, responses, and discussion among the seminar participants. A report of the seminar summarizing the findings of the seminar is published separately under the title “IDEE Special Report: 25 Years After 1989: Reflections on Unfin- ished Revolutions.” The seminar, Special Issue of Uncaptive Minds, and Special Report were made possible in part by a grant of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. • The Special Issue of Uncaptive Minds and the Special Report are available online at IDEE’s new web site, www.idee-us.org. • Requests for permission for reproduction of the Special Issue of Uncaptive Minds or “IDEE Special Report: 25 Years After 1989” should be sent to: [email protected]. Send ATTN: Permission for Use. • Price: Print copies are available for cost of shipping and handling as listed below. Send a request with a check or money order made out to “IDEE” to: IDEE 1718 M Street, No. 147 Washington, DC 20036 Special Issue of Uncaptive Minds: 25 Years After 1989 US: Single Copy: $7.50. Additional Copies at: $5.00/apiece. IDEE Special Report: “25 Years After 1989” US: Single Copy: $5.00. -

Estonia “Has No Time”: Existential Politics at the End of Empire

Estonia “has no time”: Existential Politics at the End of Empire Kaarel PIIRIMÄE Associate Professor in History University of Helsinki (FI) University of Tartu (EE) [email protected] Abstract This article is about the Estonian transition from the era of perestroika to the 1990s. It suggests that the Estonian national movement considered the existence of the nation to be threatened. Therefore, it used the window of opportunity presented by perestroika to take control of time and break free of the empire. This essay has the following theoretical premises. First, Estonia was not engaged in “normal politics” but in something that I will conceptualise, following the Copenhagen School, as “existential politics.” Second, the key feature of existential politics is time. I will draw on the distinction, made in the ancient Greek thought, between the gods Chronos and Kairos. By applying these concepts to Estonia, I suggest Kairos presented the opportunity to break the normal flow of time and the decay of Socialism (Chronos) in order to fight for the survival of the Estonian nation. The third starting point is Max Weber’s historical sociology, particularly his notion of “charisma,” developed in Stephen Hanson’s interpretation of the notions of time in Marxism-Leninism-Stalinism. Based on this, I will argue that Estonian elites thought they were living in extraordinary times that required the breaking of the normal flow of time, which was thought to be corroding the basis of the nation’s existence. Keywords: Notions of Time, Existential Politics, Perestroika, Estonia, Soviet Union, Social Transitions. Résumé Cet article porte sur la transition estonienne de la perestroïka aux années 1990.