Post-Printstuart Burch & Ulf Zander

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Download

Ajalooline Ajakiri, 2016, 3/4 (157/158), 477–511 Historical consciousness, personal life experiences and the orientation of Estonian foreign policy toward the West, 1988–1991 Kaarel Piirimäe and Pertti Grönholm ABSTRACT The years 1988 to 1991 were a critical juncture in the history of Estonia. Crucial steps were taken during this time to assure that Estonian foreign policy would not be directed toward the East but primarily toward the integration with the West. In times of uncertainty and institutional flux, strong individuals with ideational power matter the most. This article examines the influence of For- eign Minister Lennart Meri’s and Prime Minister Edgar Savisaar’s experienc- es and historical consciousness on their visions of Estonia’s future position in international affairs. Life stories help understand differences in their horizons of expectation, and their choices in conducting Estonian diplomacy. Keywords: historical imagination, critical junctures, foreign policy analysis, So- viet Union, Baltic states, Lennart Meri Much has been written about the Baltic states’ success in breaking away from Eastern Europe after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, and their decisive “return to the West”1 via radical economic, social and politi- Research for this article was supported by the “Reimagining Futures in the European North at the End of the Cold War” project which was financed by the Academy of Finland. Funding was also obtained from the “Estonia, the Baltic states and the Collapse of the Soviet Union: New Perspectives on the End of the Cold War” project, financed by the Estonian Research Council, and the “Myths, Cultural Tools and Functions – Historical Narratives in Constructing and Consolidating National Identity in 20th and 21st Century Estonia” project, which was financed by the Turku Institute for Advanced Studies (TIAS, University of Turku). -

Preoccupied by the Past

© Scandia 2010 http://www.tidskriftenscandia.se/ Preoccupied by the Past The Case of Estonian’s Museum of Occupations Stuart Burch & Ulf Zander The nation is born out of the resistance, ideally without external aid, of its nascent citizens against oppression […] An effective founding struggle should contain memorable massacres, atrocities, assassina- tions and the like, which serve to unite and strengthen resistance and render the resulting victory the more justified and the more fulfilling. They also can provide a focus for a ”remember the x atrocity” histori- cal narrative.1 That a ”foundation struggle mythology” can form a compelling element of national identity is eminently illustrated by the case of Estonia. Its path to independence in 98 followed by German and Soviet occupation in the Second World War and subsequent incorporation into the Soviet Union is officially presented as a period of continuous struggle, culminating in the resumption of autonomy in 99. A key institution for narrating Estonia’s particular ”foundation struggle mythology” is the Museum of Occupations – the subject of our article – which opened in Tallinn in 2003. It conforms to an observation made by Rhiannon Mason concerning the nature of national museums. These entities, she argues, play an important role in articulating, challenging and responding to public perceptions of a nation’s histories, identities, cultures and politics. At the same time, national museums are themselves shaped by the nations within which they are located.2 The privileged role of the museum plus the potency of a ”foundation struggle mythology” accounts for the rise of museums of occupation in Estonia and other Eastern European states since 989. -

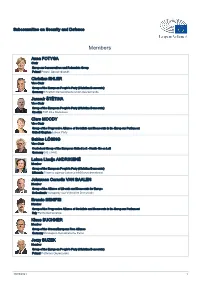

List of Members

Subcommittee on Security and Defence Members Anna FOTYGA Chair European Conservatives and Reformists Group Poland Prawo i Sprawiedliwość Christian EHLER Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Germany Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands Jaromír ŠTĚTINA Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Czechia TOP 09 a Starostové Clare MOODY Vice-Chair Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament United Kingdom Labour Party Sabine LÖSING Vice-Chair Confederal Group of the European United Left - Nordic Green Left Germany DIE LINKE. Laima Liucija ANDRIKIENĖ Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Lithuania Tėvynės sąjunga-Lietuvos krikščionys demokratai Johannes Cornelis VAN BAALEN Member Group of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Netherlands Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie Brando BENIFEI Member Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament Italy Partito Democratico Klaus BUCHNER Member Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance Germany Ökologisch-Demokratische Partei Jerzy BUZEK Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Poland Platforma Obywatelska 30/09/2021 1 Aymeric CHAUPRADE Member Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy Group France Les Français Libres Javier COUSO PERMUY Member Confederal Group of the European United Left - Nordic Green Left Spain Independiente Arnaud DANJEAN Member Group of the European People's Party -

Rein Taagepera, University of California, Irvine

ESTONIA IN SEPTEMBER 1988: STALINISTS, CENTRISTS AND RESTORATIONISTS Rein Taagepera, University of California, Irvine The situation in Estonia is changing beyond recognition by the month. A paper I gave in late April on this topic needed serious updating for an encore in early June and needs a complete rewrite now, in early September 1988.x By the rime it reaches the readers, the present article will be outdated, too. Either liberalization will have continued far beyond the present stage or a brutal back- lash will have cut it short. Is the scholar reduced to merely chronicling events? Not quite. There are three basic political currents that took shape a year ago and are likely to continue throughout further liberalization and even a crackdown. This framework will help to add analytical perspective to the chronicling. Political Forces in Soviet Estonia Broadly put, three political forces are vying for prominence in Estonia: Stalinists who want to keep the Soviet empire intact, perestroika-minded cen- trists whose goal is Estonia's sovereignty within a loose Soviet confederation, and restorationists who want to reestablish the pre-WWII Republic of Estonia. All three have appreciable support within the republic population. In many cases the same person is torn among all three: Emotionally he might yearn for the independence of the past, rationally he might hope only for a gradual for- marion of something new, and viscerally he might try to hang on to gains made under the old rules. (These gains include not only formal careers but much more; for instance, a skillful array of connections to obtain scarce consumer goods, lovingly built over a long time, would go to waste in an economy of plenty.) 1. -

Eesti Rahvusliku Sõltumatuse Partei

Eesti Rahvusliku Sõltumatuse Partei ERSP aeg MTÜ Magna Memoria 2008 g Sisukord Vabariigi President Toomas Hendrik Ilves. Eessõna ... 12 Tunne Kelam. ERSP - 20 aastat ... 16 Jaan Tammsalu. ERSP ja vaimulikud ... 21 Mati Kiirend. ERSP - demokraatlike liikumiste järjepidevuse kandja ... 24 Jüri Adams. ERSP arenguetapid ... 40 Lagle Parek. Stalinismiohvrite mälestusmärk ... 56 Valev Kruusa/u kõne Hirvepargi miitingul23.08.1988 ..62 Vello Salum. Kommunismiohvrite memoriaal Pilistveres ... 64 Lagle Parek. Koos ja eraldi kurjuse impeeriumi lammutamas ... 69 Mari-Ann Kelam. Eesti pagulaskonna vabadusvõitlus ja ERSP ... 96 Linnart Mäll. Esindamata Rahvaste Organisatsioon ... 110 Jüri Adams. ERSP ja põhiseadus ... 114 Andres Mäe. ERSP ja valimised ... 130 Viktor Niitsoo. Miks ERSP ei kestnud? ... 144 Eve Pärnaste. ERSP TORMILINE ALGUS. Kronoloogia Eellood: 1987 ... 154 1988... 160 21. jaanuar. Ettepanek Eesti Rahvusliku Sõltumatuse Partei loomiseks ... 165 2.veebruar ... 169 24. veebruari meeleavaldused ... 183 25. märtsi meeleavaldused ... 199 21. aprill. ERSP Korraldava Toimkonna moodustamine ... 210 l.mai ... 212 11. mai. ERSP Korraldava Toimkonna dokumendid: . Avalik kiri ENSV Ülemnõukogu Presiidiumile ... 2.18 . Üleskutse ENSV Ülemnõukogule, ENSV Ministrite Nõukogule, ENSV Prokuratuurile, ENSV Justiitsministeeriumile ... 220 Abipalve rahvusvahelistele abistamisorganisatsioonidele ... 221 Sisukord 4. juuni. Eesti I Sõltumatu Noortefoorum. ERSP sõnavõtud: Eve Pärnaste ... 229 Arvo Pesti ... 231 Andres Mäe ... 233 14.juuni miitingud ... 235 1. -

Integrating the Central European Past Into a Common Narrative: the Mobilizations Around the ’Crimes of Communism’ in the European Parliament Laure Neumayer

Integrating the Central European Past into a Common Narrative: the mobilizations around the ’crimes of Communism’ in the European Parliament Laure Neumayer To cite this version: Laure Neumayer. Integrating the Central European Past into a Common Narrative: the mobiliza- tions around the ’crimes of Communism’ in the European Parliament. Journal of Contemporary European Studies, Taylor & Francis (Routledge), 2015, Transnational Memory Politics in Europe: Interdisciplinary Approaches 23 (3), pp.344-363. 10.1080/14782804.2014.1001825. hal-01355450 HAL Id: hal-01355450 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01355450 Submitted on 23 Aug 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Integrating the Central European Past into a Common Narrative: the mobilizations around the ‘crimes of Communism’ in the European Parliament LAURE NEUMAYER Université Paris 1 Panthéon Sorbonne and Institut Universitaire de France, France ABSTRACT: After the Cold War, a new constellation of actors entered transnational European assemblies. Their interpretation of European history, which was based on the equivalence of the two ‘totalitarianisms’, Stalinism and Nazism, directly challenged the prevailing Western European narrative constructed on the uniqueness of the Holocaust as the epitome of evil. -

14426 Hon. Paul E. Kanjorski Hon. Ike Skelton

14426 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS, Vol. 152, Pt. 11 July 13, 2006 Vladimir Bukovsky—Cambridge Univer- Michael McFaul—Stanford University, US; intendent of the Wyoming Valley West School sity, UK; Alan Mendoza—Executive Director, Henry District. Leos Carax—Film director, France; Jackson; Society, UK; Mr. Piazza received his Bachelor of Science Patrice Che´reau—Film and theater direc- Marianne Mikko—Member, European Par- tor, France; liament, Estonia; degree from Mansfield University and his Mas- Daniel Cohn-Bendit—Member, European; Tim Montgomerie—Editor, ter of Science degree from Wilkes University. Parliament, Germany; ConservativeHome.com; His post-graduate work includes principal cer- Pierre Daix—Writer, France; Martin Palousˇ—Permanent Czech Repub- tification and a superintendent’s letter of eligi- Prof. Nicholas Daniloff—Northeastern Uni- lic; Representative to the United Nations; bility from Temple University. versity, US; former Czech Ambassador to the US; Mr. Piazza began his career with Wyoming Ruth Daniloff—Writer, US; Carlo di Pamparato—Children of Chechnya Valley West School District in 1971. Over the Fertilio Dario—Comitatus libertates; Action; Relief Mission (CCHARM), UK; past 35 years, Mr. Piazza has taught elemen- Franco Debennedetti—Senator, Italy; Richard Pipes—Harvard University, US; Martin Dewhirst—University of Glasgow, Daniel Pipes—Writer, US; tary grades ranging from kindergarten through Scotland; Daniel Pletka—American Enterprise Insti- sixth grade in subject areas including mathe- Freimut Duve—Former member of the Ger- tute (AEI), US; matics, social studies and reading. man Bundestag; Organisation for Security Oksana Ragazzi—UK; He was an instructional support specialist, and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) Rep- Josep Ramoneda—Philosopher, Center of head teacher and department chairperson. -

Theme 4 What Is the Unfinished Business?

78 Uncaptive Minds Special Issue • 25 Years After 1989 Theme 4 What is the Unfinished Business? IRENA LASOTA We are initiating the topic that is at the heart of this seminar. We have here four speakers—Isa Gambar from Azerbaijan, Tunne Kelam from Estonia, and Vytautas Landsbergis from Lithuania, who were not only very active during the events of 1988–91, but may be described as the very conscience of the independence movements in their countries. Mustafa Dzhemilev is the national leader of the Crimean Tatars and may also be described as the conscience of the Soviet human rights movement. Panel Discussion Mustafa Dzhemilev, Tunne Kelam, Vytautas Landsbergis & Isa Gambar Mustafa Dzhemilev To tell you the truth, I am not really ready to participate in this aca- demic seminar. I asked Irena what I should speak about and she said the topic should really be “How to liberate Crimea.” Of course, if I knew how to liberate Crimea, I wouldn’t be participating in conferences, I would be liberating Crimea. So if we are not liberating Crimea yet, let me talk about the situation as it is. Firstly, what are the consequences of the Russian occupation for the Crimean Tatars, the indigenous nation of the Crimean peninsula? They are dramatic. As you know very well, the Crimean Tatars survived the mass depor- tation from Crimea in 1944 and the partial genocide perpetrated by Stalin. We survived over decades and worked in a democratic and peaceful way to return to our historic homeland, the Crimean Tatars’ motherland. From the moment of the declaration of independence of Ukraine, the Crimean Tatars were a well-organized group within Crimea that could counteract the Russian separatist movement supported by Moscow. -

Candidate Party -- Estonia

Estonia1 Group in the Link to the Link to the party’s official Link to the National Parties European official Slogan Link to the detailed list site programme Parliament camaign site Õiged otsused http://www.irl.ee/ Pro Patria Union-Res http://www.ir raskel ajal! http://www.irl.ee/et/E et/EP- Publica (IRL)2 www.irl.ee/en l.ee/et/EP- (The good P- valimised/Program Isamaa ja Res Publica Liit valimised decision in valimised/Kandidaadid m hard times) Inimesed http://www.s eelkõige: uus http://www.sotsde Social Democratic Party otsdem.ee/ind suund http://www.sotsdem.ee m.ee/index.php?arti (SDE) ex.php?article Euroopale /index.php?article_id=9 www.sotsdem.ee cle_id=1162&img= Sotsiaaldemokraatlik _id=910&page (People first, 10&page=80&action=ar 1&page=80&action Erakond =80&action=a a new ticle& =article& rticle& direction for Europe) http://ep2009 .reform.ee/ind ex.php?utm_s Vali Euroopa ource=reform. tasemel Reform Party (RE) ee&utm_medi http://ep2009.refor http://ep2009.reform.e www.reform.ee tegijad! Eesti Reformierakond um=banner&u m.ee/programm e/kandidaadid (Choose your tm_content=a leaders) valeht&utm_c ampaign=ep2 009 1 Updated 27/05/09 2 The parties highlighted in blue are the governing parties Centre Party http://kesker http://www.keskerakon (K) www.keskerakond.ee akond.ee/tegij d.ee/eurovalimised/est Eesti Keskerakond ad / Vali uus http://rohelin http://roheline.erakond Greens http://roheline.era energia! www.roheline.erakond.ee e.erakond.ee/i .ee/index.php/Kandidaa (EER) kond.ee/images/d/ (Choose the ndex.php/Vali tide_%C3%BCleriiklik_ -

Independence Day Speech by Tunne Kelam 1989

INDEPENDENCE DAY SPEECH BY TUNNE KELAM 1989 This speech, calling for registration of Estonian citizens and the formation of a Congress of Estonia, was given by Tunne Kelam, member of the board of the Estonian National Independence Party and Chairman of the Citizens' Committees General Organizing Committee, at ceremonies commemorating the 71st anniversary of Estonian independence on 24 February 1989. The event was sponsored jointly by the Estonian Heritage Society and the Estonian National Independence Party in the concert hall "Estonia" theater. Independence Day Speech Tunne Kelam Dear compatriots, honored guests! Speaking for the Estonian National Independence Party, I am happy to announce that at its session of February 21st, the executive council of the E.N.I.P. approved a declaration analogous to the one just presented by the Estonian Heritage Society. We already know that the Estonian Christian Union joined with it on February 22nd. This signifies a unified platform of action by the Estonian Heritage Society, the Estonian National Independence Party and the Estonian Christian Union, enabling us to prepare for the formation of a real and true popular representative body, by first initiating an investigation to ascertain those individuals having the legal and moral right presently to participate in determining the future of Estonia. I call on all other independent organizations and individuals in Estonia to join this program and to embark on a road of true initiative, a road the people have truly chosen, a road that will take us toward true independence. The history of the observation of February 24 in occupied Estonia has proven the indispensability of such special days. -

Seminar on the Participatory Democracy in Central and Eastern Europe Today: Challenges and Perspectives

Seminar on the Participatory democracy in central and eastern Europe today: challenges and perspectives p r o c e e d i n g s Vilnius, 3-5 July 1997 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. OPENING SESSION Mr Gunnar JANSSON, Chair of the Committee on Parliamentary and Public relations of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe............................................................................................................... 5 Welcoming address by Mr Vytautas LANDSBERGIS, Speaker of the Lithuanian Parliament ............................................................................... 6 Introduction by Mr Andreas GROSS, Member of the National Council (Switzerland), General Rapporteur of the Committee on Parliamentary and Public Relations of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe..................................................................................................... 7 II.WORKING SESSION I ........................................................................................................... 9 Theme I: Participatory democracy in the Baltic States, before and after the communist regime Rapporteur: Mr Henn-Jüri UIBOPUU, Professor at the University of Salzburg, Tallinn (Estonia).................................................................... 9 Observations : Mr Rimantas DAGYS, Vice-Chair of the Foreign Affairs Committee of the Lithuanian Seimas ...................................................... 11 Mr Tunne KELAM, Deputy Speaker of the Riigikogu (Estonia), Vice-Chair of the Committee on Parliamentary -

IDEE Special Report

Institute for Democracy in Eastern Europe Special Report: 25 Years After 1989 Reflections on Unfinished Revolutions Levan Berdzenishvili • Ales Bialiatski • Eric Chenoweth Gábor Demszky • Miljenko Dereta • Arkady Dubnov Maria Dubnova • Sergei Duvanov • Mustafa Dzhemilev Smaranda Enache • Charles Fairbanks • Isa Gambar • Ivlian Haindrava Arif Hajili • Tunne Kelam • Vytautas Landsbergis • Irena Lasota Maciej Strzembosz • Petruška Šustrová • Tatiana Vaksberg • Vincuk Viacˇorka INSTITUTE FOR DEMOCRACY IN EASTERN EUROPE SPECIAL REPORT 25 YEARS AFTER 1989: REFLECTIONS ON UNFINISHED REVOLUTIONS INSTITUTE FOR DEMOCRACY IN EASTERN EUROPE 1718 M STREET • NO. 147 • WASHINGTON, DC 20036 TEL.: (202) 361-9346 • EMAIL: [email protected] • WEB PAGE: WWW.IDEE-US.ORG ii Institute for Democracy in Eastern Europe • Special Report INSTITUTE FOR DEMOCRACY IN EASTERN EUROPE SPECIAL REPORT 25 YEARS AFTER 1989: REFLECTIONS ON UNFINISHED REVOLUTIONS AUTHORS: ERIC CHENOWETH AND IRENA LASOTA Cover design by Małgorzata Flis. © Copyright 2015 by the Institute for Democracy in Eastern Europe. The Special Report “25 Years After 1989: Reflections on Unfinished Revolutions” was written and edited by Eric Chenoweth and Irena Lasota based on the papers and transcript of the proceedings of the seminar organized by the Institute for Democracy in Eastern Europe (IDEE) on October 3–5, 2014 in Warsaw, Poland, which was held under the title “25 Years After 1989: Time for Reflection on Unfinished Business.” The full proceedings, including the presentation of papers and dialogue of the participants, are being published as a special issue of Uncaptive Minds, the journal of information and analysis published by IDEE from 1988–1997. The authors thank Charles Fairbanks for serving as the seminar’s rapporteur and for his assistance and comments in preparing the report—as well as all the participants for their contributions and comments.