Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minorities and Majorities in Estonia: Problems of Integration at the Threshold of the Eu

MINORITIES AND MAJORITIES IN ESTONIA: PROBLEMS OF INTEGRATION AT THE THRESHOLD OF THE EU FLENSBURG, GERMANY AND AABENRAA DENMARK 22 to 25 MAY 1998 ECMI Report #2 March 1999 Contents Preface 3 The Map of Estonia 4 Ethnic Composition of the Estonian Population as of 1 January 1998 4 Note on Terminology 5 Background 6 The Introduction of the Seminar 10 The Estonian government's integration strategy 11 The role of the educational system 16 The role of the media 19 Politics of integration 22 International standards and decision-making on the EU 28 Final Remarks by the General Rapporteur 32 Appendix 36 List of Participants 37 The Integration of Non-Estonians into Estonian Society 39 Table 1. Ethnic Composition of the Estonian Population 43 Table 2. Estonian Population by Ethnic Origin and Ethnic Language as Mother Tongue and Second Language (according to 1989 census) 44 Table 3. The Education of Teachers of Estonian Language Working in Russian Language Schools of Estonia 47 Table 4 (A;B). Teaching in the Estonian Language of Other Subjects at Russian Language Schools in 1996/97 48 Table 5. Language Used at Home of the First Grade Pupils of the Estonian Language Schools (school year of 1996/97) 51 Table 6. Number of Persons Passing the Language Proficiency Examination Required for Employment, as of 01 August 1997 52 Table 7. Number of Persons Taking the Estonian Language Examination for Citizenship Applicants under the New Citizenship Law (enacted 01 April 1995) as of 01 April 1997 53 2 Preface In 1997, ECMI initiated several series of regional seminars dealing with areas where inter-ethnic tension was a matter of international concern or where ethnopolitical conflicts had broken out. -

Ex Injuria Jus Non Oritur

Ex injuria jus non oritur Periaatteet ja käytäntö Viron tasavallan palauttamisessa Veikko Johannes Jarmala Helsingin yliopisto Valtiotieteellinen tiedekunta Poliittinen historia Pro gradu -tutkielma toukokuu 2017 Tiedekunta/Osasto – Fakultet/Sektion – Faculty Laitos – Institution – Department Valtiotieteellinen tiedekunta Politiikan ja talouden tutkimuksen laitos Tekijä – Författare – Author Veikko Jarmala Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title Ex injuria jus non oritur – Periaatteet ja käytäntö Viron tasavallan palauttamisessa Oppiaine – Läroämne – Subject Poliittinen historia Työn laji – Arbetets art – Level Aika – Datum – Month and year Sivumäärä – Sidoantal – Number of pages pro gradu-tutkielma toukokuu 2017 136 Tiivistelmä – Referat – Abstract Oikeudellinen jatkuvuus (vir. õiguslik järjepidevus) on Viron tasavallan valtioidentiteetin perusta. Vuodesta 1944 lähtien pakolaisyhteisö oli haaveillut Viron vapauttamisesta ja tasavallan palauttamisesta. Se piti yllä pakolaistoiminnassaan oikeudellista jatkuvuutta, vaikkakin sen määrittelyprosessi ei ollut lainkaan sovinnollista pakolaisuuden alkuvuosina. Ulko-Viro ja koti-Viro olivat etäällä toisistaan aina 1980-luvun loppuun asti, jolloin Neuvostoliiton uudistuspolitiikka avasi mahdollisuuden yhteydenpitoon. Perestroika nosti ensin vaatimukset Eestin SNT:n suuremmasta itsehallinnosta, jota alkoi ajaa perestroikan tueksi perustettu Viron kansanrintama johtajanaan Edgar Savisaar. IME-ohjelman (Isemajandav Eesti) tuli pelastaa neuvosto-Eesti, mutta kansanrintaman vastustajaksi perustettu Interliike -

List of Prime Ministers of Estonia

SNo Name Took office Left office Political party 1 Konstantin Päts 24-02 1918 26-11 1918 Rural League 2 Konstantin Päts 26-11 1918 08-05 1919 Rural League 3 Otto August Strandman 08-05 1919 18-11 1919 Estonian Labour Party 4 Jaan Tõnisson 18-11 1919 28-07 1920 Estonian People's Party 5 Ado Birk 28-07 1920 30-07 1920 Estonian People's Party 6 Jaan Tõnisson 30-07 1920 26-10 1920 Estonian People's Party 7 Ants Piip 26-10 1920 25-01 1921 Estonian Labour Party 8 Konstantin Päts 25-01 1921 21-11 1922 Farmers' Assemblies 9 Juhan Kukk 21-11 1922 02-08 1923 Estonian Labour Party 10 Konstantin Päts 02-08 1923 26-03 1924 Farmers' Assemblies 11 Friedrich Karl Akel 26-03 1924 16-12 1924 Christian People's Party 12 Jüri Jaakson 16-12 1924 15-12 1925 Estonian People's Party 13 Jaan Teemant 15-12 1925 23-07 1926 Farmers' Assemblies 14 Jaan Teemant 23-07 1926 04-03 1927 Farmers' Assemblies 15 Jaan Teemant 04-03 1927 09-12 1927 Farmers' Assemblies 16 Jaan Tõnisson 09-12 1927 04-121928 Estonian People's Party 17 August Rei 04-121928 09-07 1929 Estonian Socialist Workers' Party 18 Otto August Strandman 09-07 1929 12-02 1931 Estonian Labour Party 19 Konstantin Päts 12-02 1931 19-02 1932 Farmers' Assemblies 20 Jaan Teemant 19-02 1932 19-07 1932 Farmers' Assemblies 21 Karl August Einbund 19-07 1932 01-11 1932 Union of Settlers and Smallholders 22 Konstantin Päts 01-11 1932 18-05 1933 Union of Settlers and Smallholders 23 Jaan Tõnisson 18-05 1933 21-10 1933 National Centre Party 24 Konstantin Päts 21-10 1933 24-01 1934 Non-party 25 Konstantin Päts 24-01 1934 -

The Estonian Russian Divide: Examining Social Diversity in Estonia with Cross-National Survey Data

The Estonian Russian Divide: Examining Social Diversity in Estonia with Cross-National Survey Data Christina Maimone Department of Political Science Stanford University April 6, 2004 Draft Since Estonia’s separation from the Soviet Union, Estonians and Russians in Estonia have struggled to live together as one society. While Estonians and Russian-Estonians1 may never have been a single integrated society, the conflict between Estonians and Russian-Estonians intensified during the formation of the independent Estonian state. During the process of establishing a constitution and new government in post-Soviet Estonia, Estonian was made the only official language of the state.2 Citizenship was granted automatically only to those who had ancestors with Estonian citizenship prior to the Soviet occupation in 1940.3 This prevented the vast majority of Russians in Estonia, approximately one-third of the residents of Estonia at the time, from being able to gain Estonian citizenship. In addition to the exclusion from citizenship, some Estonians encouraged Russians who had been located in Estonia during the Soviet occupation to leave Estonia and return to Russia. Some Russian-Estonians did migrate back to Russia, but most of the Russian-Estonians made the decision to stay where they had been living, in come cases, for their entire lives. For those without Estonian ancestors, the Estonian Law on Citizenship requires passing an Estonian language examination. Estonian is considered to be a difficult language to learn, and it is in a different language family than Russian. The language programs designed to prepare individuals to take the language examination were drastically under-funded through the 1990s, which prevented those wanting to learn Estonian from being able to. -

Public Opi Io -Buildi Gi Mass Media: a Media A

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DSpace at Tartu University Library TARTU ÜLIKOOL Faculty of Social Sciences and Education Centre for Baltic Studies Annika Bostelmann PUBLIC OPIIO-BUILDIG I MASS MEDIA: A MEDIA AALYSIS OF ESTOIA’S UCLEAR EERGY DEBATE I 2011 Master’s Thesis Supervisor: Prof. Peeter Vihalemm Tartu 2012 (BACKSIDE OF TITLE PAGE) This thesis conforms to the requirements for a Master’s thesis [Prof. Peeter Vihalemm, January 6th, 2012](signature of the supervisor and date) Admitted for defense [January 9th, 2012](date) Head of Chair: [Dr. Heiko Pääbo, January 9th, 2012](name, signature and date) Chairperson of the Defense Committee [Dr. Heiko Pääbo](signature) The thesis is 24,965 words in length (excluding bibliographical references and appendices). I have written this Master’s thesis independently. Any ideas or data taken from other authors or other sources have been fully referenced. [Annika Bostelmann, January 8th, 2012](signature of author and date) Student code: A95753 Acknowledgement: The author would like to thank Prof. Peeter Vihalemm and Dr. Heiko Pääbo for their inspiration and support in the process of creating her thesis, Maio Vaniko, Viacheslav Morozov, and Maie Kiisel for their assistance. Further thanks go to Kardi Järvpõld, Päivi Pütsepp, Eric Benjamin Seufert, and Iva Milutinovič for their criticism and linguistic support, and the author’s family for their encouragement. ABSTRACT The partial meltdown at Japan’s Fukushima power plant in 2011 has spread more than radiation: It caused a wave of dispute in many countries about the use of nuclear energy and forced those countries to re-evaluate their national energy independence given the risks posed by a plant. -

In Words and Images

IN WORDS AND IMAGES 2017 Table of Contents 3 Introduction 4 The Academy Is the Academy 50 Estonia as a Source of Inspiration Is the Academy... 5 Its Ponderous Birth 52 Other Bits About Us 6 Its Framework 7 Two Pictures from the Past 52 Top of the World 55 Member Ene Ergma Received a Lifetime Achievement Award for Science 12 About the fragility of truth Communication in the dialogue of science 56 Academy Member Maarja Kruusmaa, Friend and society of Science Journalists and Owl Prize Winner 57 Friend of the Press Award 57 Six small steps 14 The Routine 15 The Annual General Assembly of 19 April 2017 60 Odds and Ends 15 The Academy’s Image is Changing 60 Science Mornings and Afternoons 17 Cornelius Hasselblatt: Kalevipoja sõnum 61 Academy Members at the Postimees Meet-up 20 General Assembly Meeting, 6 December 2017 and at the Nature Cafe 20 Fresh Blood at the Academy 61 Academic Columns at Postimees 21 A Year of Accomplishments 62 New Associated Societies 22 National Research Awards 62 Stately Paintings for the Academy Halls 25 An Inseparable Part of the National Day 63 Varia 27 International Relations 64 Navigating the Minefield of Advising the 29 Researcher Exchange and Science Diplomacy State 30 The Journey to the Lindau Nobel Laureate 65 Europe “Mining” Advice from Academies Meetings of Science 31 Across the Globe 66 Big Initiatives Can Be Controversial 33 Ethics and Good Practices 34 Research Professorship 37 Estonian Academy of Sciences Foundation 38 New Beginnings 38 Endel Lippmaa Memorial Lecture and Memorial Medal 40 Estonian Young Academy of Sciences 44 Three-minute Science 46 For Women in Science 46 Appreciation of Student Research Efforts 48 Student Research Papers’ π-prizes Introduction ife in the Academy has many faces. -

Preoccupied by the Past

© Scandia 2010 http://www.tidskriftenscandia.se/ Preoccupied by the Past The Case of Estonian’s Museum of Occupations Stuart Burch & Ulf Zander The nation is born out of the resistance, ideally without external aid, of its nascent citizens against oppression […] An effective founding struggle should contain memorable massacres, atrocities, assassina- tions and the like, which serve to unite and strengthen resistance and render the resulting victory the more justified and the more fulfilling. They also can provide a focus for a ”remember the x atrocity” histori- cal narrative.1 That a ”foundation struggle mythology” can form a compelling element of national identity is eminently illustrated by the case of Estonia. Its path to independence in 98 followed by German and Soviet occupation in the Second World War and subsequent incorporation into the Soviet Union is officially presented as a period of continuous struggle, culminating in the resumption of autonomy in 99. A key institution for narrating Estonia’s particular ”foundation struggle mythology” is the Museum of Occupations – the subject of our article – which opened in Tallinn in 2003. It conforms to an observation made by Rhiannon Mason concerning the nature of national museums. These entities, she argues, play an important role in articulating, challenging and responding to public perceptions of a nation’s histories, identities, cultures and politics. At the same time, national museums are themselves shaped by the nations within which they are located.2 The privileged role of the museum plus the potency of a ”foundation struggle mythology” accounts for the rise of museums of occupation in Estonia and other Eastern European states since 989. -

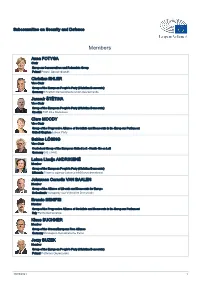

List of Members

Subcommittee on Security and Defence Members Anna FOTYGA Chair European Conservatives and Reformists Group Poland Prawo i Sprawiedliwość Christian EHLER Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Germany Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands Jaromír ŠTĚTINA Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Czechia TOP 09 a Starostové Clare MOODY Vice-Chair Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament United Kingdom Labour Party Sabine LÖSING Vice-Chair Confederal Group of the European United Left - Nordic Green Left Germany DIE LINKE. Laima Liucija ANDRIKIENĖ Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Lithuania Tėvynės sąjunga-Lietuvos krikščionys demokratai Johannes Cornelis VAN BAALEN Member Group of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Netherlands Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie Brando BENIFEI Member Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament Italy Partito Democratico Klaus BUCHNER Member Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance Germany Ökologisch-Demokratische Partei Jerzy BUZEK Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Poland Platforma Obywatelska 30/09/2021 1 Aymeric CHAUPRADE Member Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy Group France Les Français Libres Javier COUSO PERMUY Member Confederal Group of the European United Left - Nordic Green Left Spain Independiente Arnaud DANJEAN Member Group of the European People's Party -

Estonian Academy of Sciences Yearbook 2018 XXIV

Facta non solum verba ESTONIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES YEARBOOK FACTS AND FIGURES ANNALES ACADEMIAE SCIENTIARUM ESTONICAE XXIV (51) 2018 TALLINN 2019 This book was compiled by: Jaak Järv (editor-in-chief) Editorial team: Siiri Jakobson, Ebe Pilt, Marika Pärn, Tiina Rahkama, Ülle Raud, Ülle Sirk Translator: Kaija Viitpoom Layout: Erje Hakman Photos: Annika Haas p. 30, 31, 48, Reti Kokk p. 12, 41, 42, 45, 46, 47, 49, 52, 53, Janis Salins p. 33. The rest of the photos are from the archive of the Academy. Thanks to all authos for their contributions: Jaak Aaviksoo, Agnes Aljas, Madis Arukask, Villem Aruoja, Toomas Asser, Jüri Engelbrecht, Arvi Hamburg, Sirje Helme, Marin Jänes, Jelena Kallas, Marko Kass, Meelis Kitsing, Mati Koppel, Kerri Kotta, Urmas Kõljalg, Jakob Kübarsepp, Maris Laan, Marju Luts-Sootak, Märt Läänemets, Olga Mazina, Killu Mei, Andres Metspalu, Leo Mõtus, Peeter Müürsepp, Ülo Niine, Jüri Plado, Katre Pärn, Anu Reinart, Kaido Reivelt, Andrus Ristkok, Ave Soeorg, Tarmo Soomere, Külliki Steinberg, Evelin Tamm, Urmas Tartes, Jaana Tõnisson, Marja Unt, Tiit Vaasma, Rein Vaikmäe, Urmas Varblane, Eero Vasar Printed in Priting House Paar ISSN 1406-1503 (printed version) © EESTI TEADUSTE AKADEEMIA ISSN 2674-2446 (web version) CONTENTS FOREWORD ...........................................................................................................................................5 CHRONICLE 2018 ..................................................................................................................................7 MEMBERSHIP -

London School of Economics and Political Science Department of Government

London School of Economics and Political Science Department of Government Historical Culture, Conflicting Memories and Identities in post-Soviet Estonia Meike Wulf Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD at the University of London London 2005 UMI Number: U213073 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U213073 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Ih c s e s . r. 3 5 o ^ . Library British Library of Political and Economic Science Abstract This study investigates the interplay of collective memories and national identity in Estonia, and uses life story interviews with members of the intellectual elite as the primary source. I view collective memory not as a monolithic homogenous unit, but as subdivided into various group memories that can be conflicting. The conflict line between ‘Estonian victims’ and ‘Russian perpetrators* figures prominently in the historical culture of post-Soviet Estonia. However, by setting an ethnic Estonian memory against a ‘Soviet Russian’ memory, the official historical narrative fails to account for the complexity of the various counter-histories and newly emerging identities activated in times of socio-political ‘transition’. -

Parliamentary Elections

2003 PILK PEEGLISSE • GLANCE AT THE MIRROR Riigikogu valimised Parliamentary Elections 2. märtsil 2003 toimusid Eestis Riigikogu On 2 March 2003, Parliamentary elections took valimised.Valimisnimekirjadesse kanti 963 place in Estonia. The election list contained 963 kandidaati, kellest 947 kandideeris 11 erineva candidates from eleven different parties and 16 partei nimekirjas, lisaks proovis Riigikogusse independent candidates. 58.2% of eligible voters pääseda 16 üksikkandidaati. Hääletamas käis went to the polls. The Estonian Centre Party 58,2% hääleõiguslikest kodanikest. Enim hääli gained the most support of voters with 25.4% of kogus Eesti Keskerakond – 25,4%.Valimistel total votes. Res Publica – A Union for the Republic esmakordselt osalenud erakond Ühendus – who participated in the elections for the first Vabariigi Eest - Res Publica sai 24,6% häältest. time, gathered 24.6% of total votes. The parties Riigikogusse pääsesid veel Eesti Reformi- that obtained seats in the parliament were the Estonian Reform Party (17.7%), the Estonian erakond – 17,7%, Eestimaa Rahvaliit – 13,0%, People's Union (13.0%), the Pro Patria Union Isamaaliit – 7,3% ja Rahvaerakond Mõõdukad – (7.3%) and the People's Party Mõõdukad (7.0%). 7,0% Valitsuse moodustasid Res Publica, Eesti The Cabinet was formed by Res Publica, the Reformierakond ja Eestimaa Rahvaliit. Estonian Reform Party and the Estonian People's Peaministriks nimetati Res Publica esimees Union. The position of the Prime Minister went to Juhan Parts.Valitsus astus ametisse 10. aprillil Juhan Parts, chairman of Res Publica. The Cabinet 2003 ametivande andmisega Riigikogu ees. was sworn in on 10 April 2003. VALI KORD! CHOOSE ORDER! Res Publica sööst raketina Eesti poliitika- Res Publica's rocketing to the top of Estonian politics taevasse sai võimalikuks seetõttu, et suur osa was made possible by a great number of voters hääletajatest otsib üha uusi, endisest usaldus- looking for new, more reliable faces. -

Separatist Versus Centrist Forces in the Ussr, 1988-1991: Explaining the Collapse of the Soviet Internal Empire by a Strategic Alliance Approach

********************************************************* SEPARATIST VERSUS CENTRIST FORCES IN THE USSR, 1988-1991: EXPLAINING THE COLLAPSE OF THE SOVIET INTERNAL EMPIRE BY A STRATEGIC ALLIANCE APPROACH COMPARING THE BALTIC AND THE TRANSCAUCASIAN CASES: A PROGRESS REPORT By Caspar ten Dam ********************************************************* Seminar “Soviet Internal Empire: Establishment, Daily Working and Dissolution”, by Prof. Mette Skak ERASMUS, st.nr.923488 September 1993 Reproduced & proofread for publication: March 2015 CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION: Determinism within Sovietology and Why a Strategic Alliance Approach is Chosen 4 CHAPTER 1: Aspects of Strategic Alliance 8 1.1. Alignments and Realignments among Centrist and Separatist Forces, and Types of Organization 8 1.2. Typologies of Political Groups, based on the Centrist-Separatist Divide 9 CHAPTER 2. The Baltics: Successful Separatism by Moderate Senior-Junior Partnership Alliances between the Popular Fronts and the Republican Communist Parties 14 2.1. 1988: the establishments of the Popular Fronts - and Different Degrees of Cooperation with the Communist Parties 14 2.2. 1989: the Establishments of Moderate Alliances between the Popular Fronts and the Communist Parties, and the Rising Challenges of the Radical Congress Movements 17 2.3. 1990: the Moderate/Radical CP-PF Alliances fared Differently in each Republic, and the Radical Congress Alliances had Different Rates of Success 21 2.4. 1991: the Year of Allying Dangerously 25 2.5. Conclusion 30 CHAPTER 3. The Transcaucasus: Successful Ethnonationalism and Weak Separatism by Extremist Antagonistic Blocs 32 3.1. 1988: the Establishment of Nationalist Movements against the Wishes of Conservative-Reactionary Elites 32 3.2. 1989: the Rise of Extremist Nationalism, Superseding Statist Separatism, and the Failure to Establish Strategic Alliances among the Communist Parties and Opposition Movements 36 3.3.