Networks of Resistance and Opposition During the Cold War Era

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume No. 16-02 June 2016 FRIENDS ACROSS the SEA Page

Volume No. 16-02 June 2016 ROCKVILLE SISTER CITY CORPORATION NEWSLETTER www.RockvilleSisterCities.org The Rockville Sister City Corporation (RSCC) is a non-profit corporation founded in 1986 to enhance and maintain the friendship and ‘Sister City’ relationship established by the City of Rockville in 1957 with Pinneberg, Germany, based on youth, educational, cultural and commercial exchanges pursuant to the People-To-People Program initiated by President Dwight Eisenhower in 1956 to promote world peace. PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE The RSCC Mayor and Council Meet and Greet – by Drew Powell, President, RSCC Membership Appreciation event was a resounding success with more than fifty in attendance, which Another busy and productive quarter has passed for included Rockville Mayor Bridget Newton; the Rockville Sister City Corporation. The RSCC Rockville City Councilmembers, Beryl Feinberg, team, consisting of dedicated Board members, our Virginia Onley and Mark Pierzchala; General Membership, City of Rockville Elected Montgomery County Councilmember, Marc Officials and Staff as well as Friends of RSCC, is Elrich; Rockville Police Chief, Terry Treschuk; what makes our organization so successful. Here’s Rockville Acting City Manager, Craig Simoneau; some of what we achieved in the past three months: Rockville’s New City Clerk, Kathleen Conway; Rockville Assistant City Clerk, Sara Taylor- Rockville City Councilmember, Beryl Feinberg, Ferrell; former Rockville City Mayor, Steven assumed her role as RSCC’s new City Council VanGrack; former Rockville City Councilmember Liaison. Having majored in International Studies at Bob Wright; Rockville Volunteer Fire Department American University, in addition to extensive President Eric Bernard; Rockville Planning Board international travel experience, Beryl brings a member Don Hadley; all of the Rockville Sister wealth of talent and energy well suited for her City Board of Directors; Rockville Sister City position as City Council Liaison. -

Akasvayu Girona

AKASVAYU GIRONA OFFICIAL CLUB NAME: CVETKOVIC BRANKO 1.98 GUARD C.B. Girona SAD Born: March 5, 1984, in Gracanica, Bosnia-Herzegovina FOUNDATION YEAR: 1962 Career Notes: grew up with Spartak Subotica (Serbia) juniors…made his debut with Spartak Subotica during the 2001-02 season…played there till the 2003-04 championship…signed for the 2004-05 season by KK Borac Cacak…signed for the 2005-06 season by FMP Zeleznik… played there also the 2006-07 championship...moved to Spain for the 2007-08 season, signed by Girona CB. Miscellaneous: won the 2006 Adriatic League with FMP Zeleznik...won the 2007 TROPHY CASE: TICKET INFORMATION: Serbian National Cup with FMP Zeleznik...member of the Serbian National Team...played at • FIBA EuroCup: 2007 RESPONSIBLE: Cristina Buxeda the 2007 European Championship. PHONE NUMBER: +34972210100 PRESIDENT: Josep Amat FAX NUMBER: +34972223033 YEAR TEAM G 2PM/A PCT. 3PM/A PCT. FTM/A PCT. REB ST ASS BS PTS AVG VICE-PRESIDENTS: Jordi Juanhuix, Robert Mora 2001/02 Spartak S 2 1/1 100,0 1/7 14,3 1/4 25,0 2 0 1 0 6 3,0 GENERAL MANAGER: Antonio Maceiras MAIN SPONSOR: Akasvayu 2002/03 Spartak S 9 5/8 62,5 2/10 20,0 3/9 33,3 8 0 4 1 19 2,1 MANAGING DIRECTOR: Antonio Maceiras THIRD SPONSOR: Patronat Costa Brava 2003/04 Spartak S 22 6/15 40,0 1/2 50,0 2/2 100 4 2 3 0 17 0,8 TEAM MANAGER: Martí Artiga TECHNICAL SPONSOR: Austral 2004/05 Borac 26 85/143 59,4 41/110 37,3 101/118 85,6 51 57 23 1 394 15,2 FINANCIAL DIRECTOR: Victor Claveria 2005/06 Zeleznik 15 29/56 51,8 13/37 35,1 61/79 77,2 38 32 7 3 158 10,5 MEDIA: 2006/07 Zeleznik -

Helsinki Watch Committees in the Soviet Republics: Implications For

FINAL REPORT T O NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR SOVIET AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARC H TITLE : HELSINKI WATCH COMMITTEES IN THE SOVIET REPUBLICS : IMPLICATIONS FOR THE SOVIET NATIONALITY QUESTIO N AUTHORS : Yaroslav Bilinsky Tönu Parming CONTRACTOR : University of Delawar e PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATORS : Yaroslav Bilinsky, Project Director an d Co-Principal Investigato r Tönu Parming, Co-Principal Investigato r COUNCIL CONTRACT NUMBER : 621- 9 The work leading to this report was supported in whole or in part fro m funds provided by the National Council for Soviet and East European Research . NOTICE OF INTENTION TO APPLY FOR COPYRIGH T This work has been requested for manuscrip t review for publication . It is not to be quote d without express written permission by the authors , who hereby reserve all the rights herein . Th e contractual exception to this is as follows : The [US] Government will have th e right to publish or release Fina l Reports, but only in same forma t in which such Final Reports ar e delivered to it by the Council . Th e Government will not have the righ t to authorize others to publish suc h Final Reports without the consent o f the authors, and the individua l researchers will have the right t o apply for and obtain copyright o n any work products which may b e derived from work funded by th e Council under this Contract . ii EXEC 1 Overall Executive Summary HELSINKI WATCH COMMITTEES IN THE SOVIET REPUBLICS : IMPLICATIONS FOR THE SOVIET NATIONALITY QUESTION by Yaroslav Bilinsky, University of Delawar e d Tönu Parming, University of Marylan August 1, 1975, after more than two years of intensive negotiations, 35 Head s of Governments--President Ford of the United States, Prime Minister Trudeau of Canada , Secretary-General Brezhnev of the USSR, and the Chief Executives of 32 othe r European States--signed the Final Act of the Conference on Security and Cooperatio n in Europe (CSCE) . -

Know the Past ...Shape the Future

FALL 2018 - Volume 65, Number 3 WWW.AFHISTORY.ORG know the past .....Shape the Future The Air Force Historical Foundation Founded on May 27, 1953 by Gen Carl A. “Tooey” Spaatz MEMBERSHIP BENEFITS and other air power pioneers, the Air Force Historical All members receive our exciting and informative Foundation (AFHF) is a nonprofi t tax exempt organization. Air Power History Journal, either electronically or It is dedicated to the preservation, perpetuation and on paper, covering: all aspects of aerospace history appropriate publication of the history and traditions of American aviation, with emphasis on the U.S. Air Force, its • Chronicles the great campaigns and predecessor organizations, and the men and women whose the great leaders lives and dreams were devoted to fl ight. The Foundation • Eyewitness accounts and historical articles serves all components of the United States Air Force— Active, Reserve and Air National Guard. • In depth resources to museums and activities, to keep members connected to the latest and AFHF strives to make available to the public and greatest events. today’s government planners and decision makers information that is relevant and informative about Preserve the legacy, stay connected: all aspects of air and space power. By doing so, the • Membership helps preserve the legacy of current Foundation hopes to assure the nation profi ts from past and future US air force personnel. experiences as it helps keep the U.S. Air Force the most modern and effective military force in the world. • Provides reliable and accurate accounts of historical events. The Foundation’s four primary activities include a quarterly journal Air Power History, a book program, a • Establish connections between generations. -

Glomar Explorer

Approved for Release: 2018/10/01 C02623718 INTERNAL USE ONLY This publication contains clippings from the domestic and foreign press for YOUR BACKGROUND INFORMATION. Further use of selected items would rarely be advisable. NO. 13 • PAGE GOVERNMENT AFFAIRS 1 GENERAL 23 EASTERN EUROPE 34 WEST EUROPE 36 NEAR EAST 39 AFRICA 41 EAST ASIA 43 LATIN AMERICA 44 CLASSIFIED BY: 008354 » DESTROY AFTER BACKGROUNDER HAS SERVED ITS PURPOSE OR WITHIN 60 DAYS CpNPfl5ENTIAL Approved for Release: 2018/10/01 C02623718 Approved for Release: 2018/10/01 C02623718 THE NEW YORK TIMES, TUESDAY, JULY 20, 1976 The C.LA. Cloud Over the Press By Daniel Schorr ASPEN, Colo.—One of Wil liam E. Colby's less exhilarating . moments as Director of Central Intelligence was having to call a news conference to demand deletion from the Senate report on assassination plots of a dozen names, including such underworld figures as Sam Giancana and John Rosselli. However misguided the re cruitment of these worthies in . the C.I.A.’s designs on Fidel Castro, they had been promised eternal secrecy about, their roles, and, for the agency, de livering on that promise was an . article of faith. as well as law. Again, when Mr. Colby was subpoenaed by the House In-, telligerrce Committee for the names of certain intelligence officers, he faced up to a threat ened! contempt citation by mak ing ’it clear that he would rather go to jail' than com promise intelligence sources. This goes, as well, for the. names of journalists who have served the C.LA. And Mr. -

List of Prime Ministers of Estonia

SNo Name Took office Left office Political party 1 Konstantin Päts 24-02 1918 26-11 1918 Rural League 2 Konstantin Päts 26-11 1918 08-05 1919 Rural League 3 Otto August Strandman 08-05 1919 18-11 1919 Estonian Labour Party 4 Jaan Tõnisson 18-11 1919 28-07 1920 Estonian People's Party 5 Ado Birk 28-07 1920 30-07 1920 Estonian People's Party 6 Jaan Tõnisson 30-07 1920 26-10 1920 Estonian People's Party 7 Ants Piip 26-10 1920 25-01 1921 Estonian Labour Party 8 Konstantin Päts 25-01 1921 21-11 1922 Farmers' Assemblies 9 Juhan Kukk 21-11 1922 02-08 1923 Estonian Labour Party 10 Konstantin Päts 02-08 1923 26-03 1924 Farmers' Assemblies 11 Friedrich Karl Akel 26-03 1924 16-12 1924 Christian People's Party 12 Jüri Jaakson 16-12 1924 15-12 1925 Estonian People's Party 13 Jaan Teemant 15-12 1925 23-07 1926 Farmers' Assemblies 14 Jaan Teemant 23-07 1926 04-03 1927 Farmers' Assemblies 15 Jaan Teemant 04-03 1927 09-12 1927 Farmers' Assemblies 16 Jaan Tõnisson 09-12 1927 04-121928 Estonian People's Party 17 August Rei 04-121928 09-07 1929 Estonian Socialist Workers' Party 18 Otto August Strandman 09-07 1929 12-02 1931 Estonian Labour Party 19 Konstantin Päts 12-02 1931 19-02 1932 Farmers' Assemblies 20 Jaan Teemant 19-02 1932 19-07 1932 Farmers' Assemblies 21 Karl August Einbund 19-07 1932 01-11 1932 Union of Settlers and Smallholders 22 Konstantin Päts 01-11 1932 18-05 1933 Union of Settlers and Smallholders 23 Jaan Tõnisson 18-05 1933 21-10 1933 National Centre Party 24 Konstantin Päts 21-10 1933 24-01 1934 Non-party 25 Konstantin Päts 24-01 1934 -

Importance of European Remembrance for the Future of Europe

European Parliament 2019-2024 TEXTS ADOPTED P9_TA(2019)0021 Importance of European remembrance for the future of Europe European Parliament resolution of 19 September 2019 on the importance of European remembrance for the future of Europe (2019/2819(RSP)) The European Parliament, – having regard to the universal principles of human rights and the fundamental principles of the European Union as a community based on common values, – having regard to the statement issued on 22 August 2019 by First Vice-President Timmermans and Commissioner Jourová ahead of the Europe-Wide Day of Remembrance for the victims of all totalitarian and authoritarian regimes, – having regard to the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted on 10 December 1948, – having regard to its resolution of 12 May 2005 on the 60th anniversary of the end of the Second World War in Europe on 8 May 19451, – having regard to Resolution 1481 of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe of 26 January 2006 on the need for international condemnation of crimes of totalitarian Communist regimes, – having regard to Council Framework Decision 2008/913/JHA of 28 November 2008 on combating certain forms and expressions of racism and xenophobia by means of criminal law2, – having regard to the Prague Declaration on European Conscience and Communism adopted on 3 June 2008, – having regard to its declaration on the proclamation of 23 August as European Day of Remembrance for the Victims of Stalinism and Nazism adopted on 23 September 20083, 1 OJ C 92 E, 20.4.2006, p. 392. 2 OJ L 328, 6.12.2008, p. -

Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and Natural History

Proceedingsof the SUFFOLK INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND NATURAL HISTORY 4 °4vv.es`Egi vI V°BkIAS VOLUME XXV, PART 1 (published 1950) PRINTED FOR THE SOCIETY BY W. E. HARRISON & SONS, LTD., THE ANCIENT HOUSE, IPSWI611. The costof publishing this paper has beenpartially defrayedby a Grant from the Council for British Archeology. THE SUTTON HOO SHIP-BURIAL Recenttheoriesand somecommentsongeneralinterpretation By R. L. S. BRUCE-MITFORD, SEC. S.A. INTRODUCTION The Sutton Hoo ship-burial was discovered more than ten years ago. During these years especially since the end of the war in Europe has made it possible to continue the treatment and study of the finds and proceed with comparative research, its deep significance for general and art history, Old English literature and European archmology has become more and more evident. Yet much uncertainty prevails on general issues. Many questions cannot receive their final answer until the remaining mounds of the grave-field have been excavated. Others can be answered, or at any rate clarified, now. The purpose of this article is to clarify the broad position of the burial in English history and archmology. For example, it has been said that ' practically the whole of the Sutton Hoo ship-treasure is an importation from the Uppland province of Sweden. The great bulk of the work was produced in Sweden itself.' 1 Another writer claims that the Sutton Hoo ship- burial is the grave of a Swedish chief or king.' Clearly we must establish whether it is part of English archxology, or of Swedish, before we can start to draw from it the implications that we are impatient to draw. -

Ettekande Fail

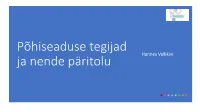

Põhiseaduse tegijad Hannes Vallikivi ja nende päritolu 1919 1920 märts aprill mai juuni juuli august sept okt nov dets jaan veebr märts aprill mai juuni MNK APSK VAK PSK I PSK II PSK III PS Uluotsa APS eelnõu Uluotsa II PS eelnõu Uluotsa I PS eelnõu Riigikohtu, kohtunike, riigikontrolöri, peastaabi, ministrite jt kommentaarid MNK APSK PSK § Palvadre § Asson, Jans, Kurs-Olesk, Oinas, Vain § Ast, Kartau, Kurs-Olesk, Neps, Vain jt § Ruubel § Anderkopp, Kalbus, Olesk, Tomberg § Anderkopp, Kalbus, Olesk, Ruubel, Strandman, Talts jt § Maim, Parts § Parts, Poska, Tõnisson, Westholm § Kuusner, Maim, Parts, Poska jt § Linnamägi § Kann § Kann, Leesment § Uluots § Uluots § Uluots § Pezold, Koch § Kruus § Loorits, Kruus § Sorokin MNK = Maanõukogu juristide komisjon; APSK = ajutise põhiseaduse komisjon; PSK = põhiseaduskomisjon; VAK = valitsemise ajutine kord; PS = põhiseadus © Hannes Vallikivi 2020 Erakondade aktiivsus (VAK) Erakondade aktiivsus (PS) kristlik rahvaerakond tööerakond rahvaerakond rahvaerakond 4% 21% 11% 34% kristlik rahvaerakond 4% maaliit 21% maaliit 12% sakslased 1% sakslased 4% venelased tööerakond 3% venelased 15% 1% sotsiaaldemokraadid esseerid 42% esseerid sotsiaaldemokraadid 0% 5% 22% Saadikute aktiivsus (VAK) Saadikute aktiivsus (PS) Tõnisson Uluots Einbund Päts Olesk Ast Vain Seljamaa Jans Sorokin Ast Jans Päts Tõnisson* Strandman Olesk Oinas Anderkopp Vain Kruus © Hannes Vallikivi 2020 MNK APSK VAK PSK PS PM KM Koht. MNK APSK VAK PSK PS PM KM Koht. Anderkopp, Ado Olesk, Lui Asson, Emma Palvadre, Anton Ast, Karl Parts, Kaarel -

LITUANUS Cumulative Index 1954-2004 (PDF)

LITUANUS Cumulative Index 1954-2004 Art and Artists [Aleksa, Petras]. See Jautokas. 23:3 (1977) 59-65. [Algminas, Arvydas]. See Matranga. 31:2 (1985) 27-32. Anderson, Donald J. “Lithuanian Bookplates Ex Libris.” 26:4 (1980) 42-49. ——. “The Art of Algimantas Kezys.” 27:1 (1981) 49-62. ——. “Lithuanian Art: Exhibition 90 ‘My Religious Beliefs’.” 36:4 (1990) 16-26. ——. “Lithuanian Artists in North America.” 40:2 (1994) 43-57. Andriußyt∂, Rasa. “Rimvydas Jankauskas (Kampas).” 45:3 (1999) 48-56. Artists in Lithuania. “The Younger Generation of Graphic Artists in Lithuania: Eleven Reproductions.” 19:2 (1973) 55-66. [Augius, Paulius]. See Jurkus. 5:4 (1959) 118-120. See Kuraus- kas. 14:1 (1968) 40-64. Außrien∂, Nora. “Außrin∂ Marcinkeviçi∆t∂-Kerr.” 50:3 (2004) 33-34. Bagdonas, Juozas. “Profile of an Artist.” 29:4 (1983) 50-62. Bakßys Richardson, Milda. ”Juozas Jakßtas: A Lithuanian Carv- er Confronts the Venerable Oak.” 47:2 (2001) 4, 19-53. Baltrußaitis, Jurgis. “Arts and Crafts in the Lithuanian Home- stead.” 7:1 (1961) 18-21. ——. “Distinguishing Inner Marks of Roerich’s Painting.” Translated by W. Edward Brown. 20:1 (1974) 38-48. [Balukas, Vanda 1923–2004]. “The Canvas is the Message.” 28:3 (1982) 33-36. [Banys, Nijol∂]. See Kezys. 43:4 (1997) 55-61. [Barysait∂, DΩoja]. See Kuç∂nas-Foti. 44:4 (1998) 11-22. 13 ART AND ARTISTS [Bookplates and small art works]. Augusts, Gvido. 46:3 (2000) 20. Daukßait∂-Katinien∂, Irena. 26:4 (1980) 47. Eidrigeviçius, Stasys 26:4 (1980) 48. Indraßius, Algirdas. 44:1 (1998) 44. Ivanauskait∂, Jurga. 48:4 (2002) 39. -

Die Hügelgräber Von Alt-Uppsala

Mag. Dr. Friedrich Grünzweig PS Proseminar: Archäologie in Skandinavien LV-Nr. 130069 WS 2015/16 Die Hügelgräber von Alt-Uppsala Mag. Ulrich Latzenhofer Matrikel-Nr. 8425222 Studienkennzahl 033 668 Studienplancode SKB241 2 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Vorbemerkung .................................................................................................................... 3 2 Grabungen und Funde ......................................................................................................... 4 3 Chronologische Einordnung ............................................................................................... 7 3.1 Hügelgräber ................................................................................................................. 7 3.2 Grabbeigaben ............................................................................................................... 7 3.3 Literarische Überlieferung ........................................................................................... 8 4 Anordnung der Hügelgräber ............................................................................................. 10 5 Literaturverzeichnis .......................................................................................................... 13 5.1 Quellen ....................................................................................................................... 13 5.2 Forschungsliteratur .................................................................................................... 13 3 1 Vorbemerkung Nach -

The South-East Baltic - a New Region of Co- Operating Polish Provinces by Malgorzata Pacuk and Tadeusz Palmowski, Poland «

The South-East Baltic - A new Region of Co- operating Polish Provinces By Malgorzata Pacuk and Tadeusz Palmowski, Poland « Abstract: The paper presents some examples of Polish coastal provinces' co-operation initiatives and activities in the Baltic Sea region. The authors pay attention to those aspects of co-operation which have been taken by local municipalities and communities. In addition to initiatives taken within the wider context, a substantial number of actions engage a limited numbers of participants, differ in kind, status and size. All the initiatives constitute a significant input to Baltic integration. Introduction The political changes which took place in Europe at the beginning of the 1990s created favourable conditions for development of the economic and intellectual potential of all states in the Baltic region. Baltic co-operation may become a key link in integration processes in Europe. Previous, current and planned co-operation activities have involved all the states in the Baltic Sea region. The dynamic developments taking place in Baltic Europe can be perceived as the most characteristic, reflecting the newly established formal and informal structures for integration and co-operation. However, it must be emphasised that institutionalised co-operation within the region is only a superstructure facilitating delimitation of an area comprising state bodies. Next in line there are regions, local communities and their projects which are the main entities of Baltic co-operation and the principal beneficiaries. Baltic countries in Europe have a long, common history and are presently undergoing a revival of their identity. The history of these countries features both examples of co- operation and of conflict.