Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and Natural History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Treatise on Combined Metalworking Techniques: Forged Elements and Chased Raised Shapes Bonnie Gallagher

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses Thesis/Dissertation Collections 1972 Treatise on combined metalworking techniques: forged elements and chased raised shapes Bonnie Gallagher Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Gallagher, Bonnie, "Treatise on combined metalworking techniques: forged elements and chased raised shapes" (1972). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Thesis/Dissertation Collections at RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TREATISE ON COMBINED METALWORKING TECHNIQUES i FORGED ELEMENTS AND CHASED RAISED SHAPES TREATISE ON. COMBINED METALWORKING TECHNIQUES t FORGED ELEMENTS AND CHASED RAISED SHAPES BONNIE JEANNE GALLAGHER CANDIDATE FOR THE MASTER OF FINE ARTS IN THE COLLEGE OF FINE AND APPLIED ARTS OF THE ROCHESTER INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY AUGUST ( 1972 ADVISOR: HANS CHRISTENSEN t " ^ <bV DEDICATION FORM MUST GIVE FORTH THE SPIRIT FORM IS THE MANNER IN WHICH THE SPIRIT IS EXPRESSED ELIEL SAARINAN IN MEMORY OF MY FATHER, WHO LONGED FOR HIS CHILDREN TO HAVE THE OPPORTUNITY TO HAVE THE EDUCATION HE NEVER HAD THE FORTUNE TO OBTAIN. vi PREFACE Although the processes of raising, forging, and chasing of metal have been covered in most technical books, to date there is no major source which deals with the functional and aesthetic requirements -

Awalkthroughblythburghvi

AA WWAALLKK tthhrroouugghh BBLLYYTTHHBBUURRGGHH VVIILLLLAAGGEE Thiis map iis from the bookllet Bllythburgh. A Suffollk Viillllage, on salle iin the church and the viillllage shop. 1 A WALK THROUGH BLYTHBURGH VILLAGE Starting a walk through Blythburgh at the water tower on DUNWICH ROAD south of the village may not seem the obvious place to begin. But it is a reminder, as the 1675 map shows, that this was once the main road to Blythburgh. Before a new turnpike cut through the village in 1785 (it is now the A12) the north-south route was more important. It ran through the Sandlings, the aptly named coastal strip of light soil. If you look eastwards from the water tower there is a fine panoramic view of the Blyth estuary. Where pigs are now raised in enclosed fields there were once extensive tracts of heather and gorse. The Toby’s Walks picnic site on the A12 south of Blythburgh will give you an idea of what such a landscape looked like. You can also get an impression of the strategic location of Blythburgh, on a slight but significant promontory on a river estuary at an important crossing point. Perhaps the ‘burgh’ in the name indicates that the first Saxon settlement was a fortified camp where the parish church now stands. John Ogilby’s Map of 1675 Blythburgh has grown slowly since the 1950s, along the roads and lanes south of the A12. If you compare the aerial view of about 1930 with the present day you can see just how much infilling there has been. -

To Blythburgh, an Essay on the Village And

AN INDEX to M. Janet Becker, Blythburgh. An Essay on the Village and the Church. (Halesworth, 1935) Alan Mackley Blythburgh 2020 AN INDEX to M. Janet Becker, Blythburgh. An Essay on the Village and the Church. (Halesworth, 1935) INTRODUCTION Margaret Janet Becker (1904-1953) was the daughter of Harry Becker, painter of the farming community and resident in the Blythburgh area from 1915 to his death in 1928, and his artist wife Georgina who taught drawing at St Felix school, Southwold, from 1916 to 1923. Janet appears to have attended St Felix school for a while and was also taught in London, thanks to a generous godmother. A note-book she started at the age of 19 records her then as a London University student. It was in London, during a visit to Southwark Cathedral, that the sight of a recently- cleaned monument inspired a life-long interest in the subject. Through a friend’s introduction she was able to train under Professor Ernest Tristram of the Royal College of Art, a pioneer in the conservation of medieval wall paintings. Janet developed a career as cleaner and renovator of church monuments which took her widely across England and Scotland. She claimed to have washed the faces of many kings, aristocrats and gentlemen. After her father’s death Janet lived with her mother at The Old Vicarage, Wangford. Janet became a respected Suffolk historian. Her wide historical and conservation interests are demonstrated by membership of the St Edmundsbury and Ipswich Diocesan Advisory Committee on the Care of Churches, and she was a Council member of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and History. -

ABSTRACT Savannah Dehart. BRACTEATES AS INDICATORS OF

ABSTRACT Savannah DeHart. BRACTEATES AS INDICATORS OF NORTHERN PAGAN RELIGIOSITY IN THE EARLY MIDDLE AGES. (Under the direction of Michael J. Enright) Department of History, May 2012. This thesis investigates the religiosity of some Germanic peoples of the Migration period (approximately AD 300-800) and seeks to overcome some difficulties in the related source material. The written sources which describe pagan elements of this period - such as Tacitus’ Germania, Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People, and Paul the Deacon’s History of the Lombards - are problematic because they were composed by Roman or Christian authors whose primary goals were not to preserve the traditions of pagans. Literary sources of the High Middle Ages (approximately AD 1000-1400) - such as The Poetic Edda, Snorri Sturluson’s Prose Edda , and Icelandic Family Sagas - can only offer a clearer picture of Old Norse religiosity alone. The problem is that the beliefs described by these late sources cannot accurately reflect religious conditions of the Early Middle Ages. Too much time has elapsed and too many changes have occurred. If literary sources are unavailing, however, archaeology can offer a way out of the dilemma. Rightly interpreted, archaeological evidence can be used in conjunction with literary sources to demonstrate considerable continuity in precisely this area of religiosity. Some of the most relevant material objects (often overlooked by scholars) are bracteates. These coin-like amulets are stamped with designs that appear to reflect motifs from Old Norse myths, yet their find contexts, including the inhumation graves of women and hoards, demonstrate that they were used during the Migration period of half a millennium earlier. -

Ritual Landscapes and Borders Within Rock Art Research Stebergløkken, Berge, Lindgaard and Vangen Stuedal (Eds)

Stebergløkken, Berge, Lindgaard and Vangen Stuedal (eds) and Vangen Lindgaard Berge, Stebergløkken, Art Research within Rock and Borders Ritual Landscapes Ritual Landscapes and Ritual landscapes and borders are recurring themes running through Professor Kalle Sognnes' Borders within long research career. This anthology contains 13 articles written by colleagues from his broad network in appreciation of his many contributions to the field of rock art research. The contributions discuss many different kinds of borders: those between landscapes, cultures, Rock Art Research traditions, settlements, power relations, symbolism, research traditions, theory and methods. We are grateful to the Department of Historical studies, NTNU; the Faculty of Humanities; NTNU, Papers in Honour of The Royal Norwegian Society of Sciences and Letters and The Norwegian Archaeological Society (Norsk arkeologisk selskap) for funding this volume that will add new knowledge to the field and Professor Kalle Sognnes will be of importance to researchers and students of rock art in Scandinavia and abroad. edited by Heidrun Stebergløkken, Ragnhild Berge, Eva Lindgaard and Helle Vangen Stuedal Archaeopress Archaeology www.archaeopress.com Steberglokken cover.indd 1 03/09/2015 17:30:19 Ritual Landscapes and Borders within Rock Art Research Papers in Honour of Professor Kalle Sognnes edited by Heidrun Stebergløkken, Ragnhild Berge, Eva Lindgaard and Helle Vangen Stuedal Archaeopress Archaeology Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Gordon House 276 Banbury Road Oxford OX2 7ED www.archaeopress.com ISBN 9781784911584 ISBN 978 1 78491 159 1 (e-Pdf) © Archaeopress and the individual authors 2015 Cover image: Crossing borders. Leirfall in Stjørdal, central Norway. Photo: Helle Vangen Stuedal All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. -

Hunnic Warfare in the Fourth and Fifth Centuries C.E.: Archery and the Collapse of the Western Roman Empire

HUNNIC WARFARE IN THE FOURTH AND FIFTH CENTURIES C.E.: ARCHERY AND THE COLLAPSE OF THE WESTERN ROMAN EMPIRE A Thesis Submitted to the Committee of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Faculty of Arts and Science. TRENT UNIVERSITY Peterborough, Ontario, Canada © Copyright by Laura E. Fyfe 2016 Anthropology M.A. Graduate Program January 2017 ABSTRACT Hunnic Warfare in the Fourth and Fifth Centuries C.E.: Archery and the Collapse of the Western Roman Empire Laura E. Fyfe The Huns are one of the most misunderstood and mythologized barbarian invaders encountered by the Roman Empire. They were described by their contemporaries as savage nomadic warriors with superior archery skills, and it is this image that has been written into the history of the fall of the Western Roman Empire and influenced studies of Late Antiquity through countless generations of scholarship. This study examines evidence of Hunnic archery, questions the acceptance and significance of the “Hunnic archer” image, and situates Hunnic archery within the context of the fall of the Western Roman Empire. To achieve a more accurate picture of the importance of archery in Hunnic warfare and society, this study undertakes a mortuary analysis of burial sites associated with the Huns in Europe, a tactical and logistical study of mounted archery and Late Roman and Hunnic military engagements, and an analysis of the primary and secondary literature. Keywords: Archer, Archery, Army, Arrow, Barbarian, Bow, Burial Assemblages, Byzantine, Collapse, Composite Bow, Frontier, Hun, Logistics, Migration Period, Roman, Roman Empire, Tactics, Weapons Graves ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my thesis advisor, Dr. -

The Book Collection of Artist and Educator Philip Rawson (1924-1995) Courtesy of the National Arts Education Archive, Yorkshire Sculpture Park

YMeDaCa: READING LIST The book collection of artist and educator Philip Rawson (1924-1995) courtesy of the National Arts Education Archive, Yorkshire Sculpture Park. With special thanks to NAEA volunteers, Jane Carlton, Judith Padden, Sylvia Greenwood and Christine Parkinson. To visit: www.ysp.co.uk/naea BOOK TITLE AUTHOR Treasures of ancient America: the arts of pre-Columbian civilizations from Mexico to Peru S K Lothrop Neo-classical England Judy Marle Bronzes from the Deccan: Lalit Kala Nos. 3-4 Douglas Barrett Ancient Peruvian art [exhibition catalogue] Laing Art Gallery. Newcastle upon Tyne The art of the Canadian Eskimo W T Lamour & Jacques Brunet [trans] The American Indians : their archaeology and pre history Dean Snow Folk art of Asia, Australia, the Americas Helmuth Th. Bossert North America Wolfgang Haberland Sacred circles: two thousand years of north American Indian art [exhibition catalogue] Ralph T Coe People of the totem: the Indians of the Pacific North-West Norman Bencroft-Hunt Mexican art Justino Fernandez Mexican art Justino Fernandez Between continents/between seas: precolumbian art of Costa Rica Suzanne Abel-Vidor et al The art of ancient Mexico Franz Feuchtwanger Angkor: art and civilization Bernard Crosier The Maori: heirs of Tane David Lewis Cluniac art of the Romanesque period Joan Evans English romanesque art 1066-1200 [exhibition catalogue] Arts Council Oceanic art Alberto Cesace Ambesi 100 Master pieces: Mohammedan & oriental The Harvard outline and reading lists for Oriental Art. Rev.ed Benjamin Rowland Jr. Shock of recognition: landscape of English Romanticism, Dutch seventeenth-century school. American primitive Sandy Lesberg (ed) American Art: four exhibitions. -

University of London Deviant Burials in Viking-Age

UNIVERSITY OF LONDON DEVIANT BURIALS IN VIKING-AGE SCANDINAVIA Ruth Lydia Taylor M. Phil, Institute of Archaeology, University College London UMI Number: U602472 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U602472 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ABSTRACT DEVIANT BURIALS IN VIKING-AGE SCANDINAVIA The thesis brings together information yielded from archaeology and other sources to provide an overall picture of the types of burial practices encountered during the Viking-Age in Scandinavia. From this, an attempt is made to establish deviancy. Comparative evidence, such as literary, runic, legal and folkloric evidence will be used critically to shed perspective on burial practices and the artefacts found within the graves. The thesis will mostly cover burials from the Viking Age (late 8th century to the mid- 11th century), but where the comparative evidence dates from other periods, its validity is discussed accordingly. Two types of deviant burial emerged: the criminal and the victim. A third type, which shows distinctive irregularity yet lacks deviancy, is the healer/witch burial. -

Birka På Björkö

45551633Gender Södertörns högskola | Institutionen för historia och samtidsstudier Masteruppsats 30 hp | Arkeologi | vårterminen 2014 Birka på Björkö Forskning, tidsanda och särställning Av: Birgitta Gärdin Handledare: Kerstin Cassel 2 Birka Hur många hedningar cirka Kan Ansgar ha kristnat i Birka? Döpte han fler än ett tjog? Var de västgötar, uppsvenskar, danskar? Är det verkligen troligt att Ansgar visste var Birka låg? Alf Henrikson Ur Tittut, 1992. Publicerad i Röster i Uppland En antologi av Göran Palm, sid 24 Teckning av Björn Berg i Svensk Historia del 1 av Alf Henrikson 1963, sid 86 ... har föranledt mig att i denna lilla uppsats, så vidt möjligt, söka undvika, att genom definitiva tolkningar af företeelserna gå en blifvande rikare erfarenhet i förväg, en försigtighet, som väl av ingen kan klandras... Ur Hjalmar Stolpens avhandling Naturhistoriska och arkeologiska underökningar på Björkö i Mälaren, 1872 Bilden på sid 1 samt bilderna på sista sidan är från Södertörns högskolas seminariegrävningar vid Båtudden, Björkö, 2008. Foto: Birgitta Gärdin och Olof Gärdin Bilden på sid 53 är hämtad från SHM Kartorna på sid 60 och sid 61 är hämtade från RAÄ 3 INNEHÅLL Inledning 5 Ett omfattande material 5 Där Birkaforskningen satt spår 6 Syfte 7 Teori 8 Metod och avgränsningar 9 Björkö – i och ur fokus 10 Stolpe startar moderna grävningar 13 Utvalt mål för att samla nationen 15 Birkaforskningen och den samtida samtiden 17 Stora ambitioner att göra fynden tillgängliga 19 New Archaeology i Birkaforskningen 20 Arkeologiintresserad kung ger pengar -

Mil Anos Da Incursão Normanda Ao Castelo De Vermoim

MIL ANOS DA INCURSÃO NORMANDA AO CASTELO DE VERMOIM COORD. MÁRIO JORGE BARROCA ARMANDO COELHO FERREIRA DA SILVA Título: Mil Anos da Incursão Normanda ao Castelo de Vermoim Coordenação: Mário Jorge Barroca, Armando Coelho Ferreira da Silva Design gráfico: Helena Lobo | www.hldesign.pt Imagem da capa: “Tapisserie de Bayeux – XIème siècle”. Avec autorisations spéciale de la Ville de Bayeux. Edição: CITCEM – Centro de Investigação Transdisciplinar Cultura, Espaço e Memória Via Panorâmica, s/n | 4150‑564 Porto | www.citcem.org | [email protected] ISBN: 978-989-8351-97-5 Depósito Legal: 450318/18 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21747/9789898351975/mil Porto, dezembro de 2018 Paginação, impressão e acabamento: Sersilito‑Empresa Gráfica, Lda. | www.sersilito.pt Trabalho cofinanciado pelo Fundo Europeu de Desenvolvimento Regional (FEDER) através do COMPETE 2020 – Programa Operacional Competitividade e Internacionalização (POCI) e por fundos nacionais através da FCT, no âmbito do projeto POCI-01-0145-FEDER-007460. VIKING SCANDINAVIANS BACK HOME AND ABROAD IN EUROPE: AND THE SPECIAL CASE OF BJÖRN AND HÁSTEINN STEFAN BRINK e for European early history so famous (or notorious with a bad reputation) vikings start to make a presence of themselves around ad 800 in the written sources, i.e. the Frankish, Anglo-Saxon and Irish annals and chronicles. Today we know that the raiding and trading by these Scandinavians started much earlier. e way this kind of external appropriation was conducted by the vikings was — if we simplify — that if they could get hold of wealth and silver for free, they took it (robbed, stole and if necessary killed o the people), if they met overwhelming resistance, they traded. -

Kirkhaugh Cairns Excavation Project Design

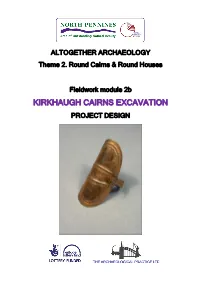

ALTOGETHER ARCHAEOLOGY Theme 2. Round Cairns & Round Houses Fieldwork module 2b KIRKHAUGH CAIRNS EXCAVATION PROJECT DESIGN Altogether Archaeology. Fieldwork module 2b. Kirkhaugh Cairns excavation. Project Design. 2 Altogether Archaeology. Fieldwork module 2b. Kirkhaugh Cairns excavation. Project Design.. Contents General introduction 1. Introduction to the Kirkhaugh Cairns 2. Scope of this Document 3. Topography and Geology 4. Archaeological Background 5. Research Aims 6. The Cairns 7. Excavation objectives 8. Methods statement 9. Finds, Environmental Sampling and human remains 10. Report 11. Archive 12. Project team 13. Communications 14. Stages, Tasks and Timetable 15. Site access and on-site facilities 16. Health & Safety and Insurance 17. References Appendices (bound separately) 1. Altogether Archaeology standard Risk Assessment. 2. Kirkhaugh Cairns module-specific Risk Assessment. Front cover illustration. The gold ‘earring’, now considered more likely to have been worn as a hair braid or attached to clothing in some way, discovered by Herbert Maryon during his excavation of Kirkhaugh Cairn 1 in 1935. This is very rare find, and dates from the very earliest phase of metalworking in Britain, about 2,400BC. It is on display in the Great North Museum, Newcastle upon Tyne. 3 Altogether Archaeology. Fieldwork module 2b. Kirkhaugh Cairns excavation. Project Design. General introduction Altogether Archaeology, largely funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund, is the North Pennines AONB Partnership’s community archaeology project. It enables volunteers to undertake practical archaeological projects with appropriate professional supervision and training. As well as raising the capacity of local groups to undertake research, the project makes a genuine contribution to our understanding of the North Pennines historic environment, thus contributing to future landscape management. -

Die Hügelgräber Von Alt-Uppsala

Mag. Dr. Friedrich Grünzweig PS Proseminar: Archäologie in Skandinavien LV-Nr. 130069 WS 2015/16 Die Hügelgräber von Alt-Uppsala Mag. Ulrich Latzenhofer Matrikel-Nr. 8425222 Studienkennzahl 033 668 Studienplancode SKB241 2 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Vorbemerkung .................................................................................................................... 3 2 Grabungen und Funde ......................................................................................................... 4 3 Chronologische Einordnung ............................................................................................... 7 3.1 Hügelgräber ................................................................................................................. 7 3.2 Grabbeigaben ............................................................................................................... 7 3.3 Literarische Überlieferung ........................................................................................... 8 4 Anordnung der Hügelgräber ............................................................................................. 10 5 Literaturverzeichnis .......................................................................................................... 13 5.1 Quellen ....................................................................................................................... 13 5.2 Forschungsliteratur .................................................................................................... 13 3 1 Vorbemerkung Nach