SSD Midterm Evaluation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

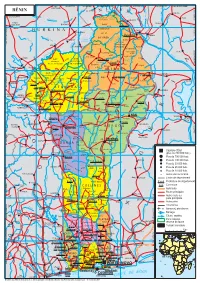

B E N I N Benin

Birnin o Kebbi !( !( Kardi KANTCHARIKantchari !( !( Pékinga Niger Jega !( Diapaga FADA N'GOUMA o !( (! Fada Ngourma Gaya !( o TENKODOGO !( Guéné !( Madécali Tenkodogo !( Burkina Faso Tou l ou a (! Kende !( Founogo !( Alibori Gogue Kpara !( Bahindi !( TUGA Suroko o AIRSTRIP !( !( !( Yaobérégou Banikoara KANDI o o Koabagou !( PORGA !( Firou Boukoubrou !(Séozanbiani Batia !( !( Loaka !( Nansougou !( !( Simpassou !( Kankohoum-Dassari Tian Wassaka !( Kérou Hirou !( !( Nassoukou Diadia (! Tel e !( !( Tankonga Bin Kébérou !( Yauri Atakora !( Kpan Tanguiéta !( !( Daro-Tempobré Dammbouti !( !( !( Koyadi Guilmaro !( Gambaga Outianhou !( !( !( Borogou !( Tounkountouna Cabare Kountouri Datori !( !( Sécougourou Manta !( !( NATITINGOU o !( BEMBEREKE !( !( Kouandé o Sagbiabou Natitingou Kotoponga !(Makrou Gurai !( Bérasson !( !( Boukombé Niaro Naboulgou !( !( !( Nasso !( !( Kounounko Gbangbanrou !( Baré Borgou !( Nikki Wawa Nambiri Biro !( !( !( !( o !( !( Daroukparou KAINJI Copargo Péréré !( Chin NIAMTOUGOU(!o !( DJOUGOUo Djougou Benin !( Guerin-Kouka !( Babiré !( Afekaul Miassi !( !( !( !( Kounakouro Sheshe !( !( !( Partago Alafiarou Lama-Kara Sece Demon !( !( o Yendi (! Dabogou !( PARAKOU YENDI o !( Donga Aledjo-Koura !( Salamanga Yérémarou Bassari !( !( Jebba Tindou Kishi !( !( !( Sokodé Bassila !( Igbéré Ghana (! !( Tchaourou !( !(Olougbé Shaki Togo !( Nigeria !( !( Dadjo Kilibo Ilorin Ouessé Kalande !( !( !( Diagbalo Banté !( ILORIN (!o !( Kaboua Ajasse Akalanpa !( !( !( Ogbomosho Collines !( Offa !( SAVE Savé !( Koutago o !( Okio Ila Doumé !( -

The Geography of Welfare in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte D'ivoire, and Togo

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized The Geography of Welfare in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, and Togo Public Disclosure Authorized Nga Thi Viet Nguyen and Felipe F. Dizon Public Disclosure Authorized 00000_CVR_English.indd 1 12/6/17 2:29 PM November 2017 The Geography of Welfare in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, and Togo Nga Thi Viet Nguyen and Felipe F. Dizon 00000_Geography_Welfare-English.indd 1 11/29/17 3:34 PM Photo Credits Cover page (top): © Georges Tadonki Cover page (center): © Curt Carnemark/World Bank Cover page (bottom): © Curt Carnemark/World Bank Page 1: © Adrian Turner/Flickr Page 7: © Arne Hoel/World Bank Page 15: © Adrian Turner/Flickr Page 32: © Dominic Chavez/World Bank Page 48: © Arne Hoel/World Bank Page 56: © Ami Vitale/World Bank 00000_Geography_Welfare-English.indd 2 12/6/17 3:27 PM Acknowledgments This study was prepared by Nga Thi Viet Nguyen The team greatly benefited from the valuable and Felipe F. Dizon. Additional contributions were support and feedback of Félicien Accrombessy, made by Brian Blankespoor, Michael Norton, and Prosper R. Backiny-Yetna, Roy Katayama, Rose Irvin Rojas. Marina Tolchinsky provided valuable Mungai, and Kané Youssouf. The team also thanks research assistance. Administrative support by Erick Herman Abiassi, Kathleen Beegle, Benjamin Siele Shifferaw Ketema is gratefully acknowledged. Billard, Luc Christiaensen, Quy-Toan Do, Kristen Himelein, Johannes Hoogeveen, Aparajita Goyal, Overall guidance for this report was received from Jacques Morisset, Elisée Ouedraogo, and Ashesh Andrew L. Dabalen. Prasann for their discussion and comments. Joanne Gaskell, Ayah Mahgoub, and Aly Sanoh pro- vided detailed and careful peer review comments. -

1 Alice BONOU FANDOHAN, Ph.D. Email

Alice BONOU FANDOHAN, Ph.D. Email: [email protected] EDUCATION - 2016 (April): Ph.D. degree, Economics of climate change, with Best Distinction, Université Cheikh Anta Diop; Senegal; Advisors: Prof. Adama Diaw - 2008 (January): DEA degree (M.Sc.) with Best Distinction, Natural Resources Management, Specialization in Environment Econometrics, Université d’Abomey- Calavi, Bénin; Advisors: Prof. Dr. Ir. Brice SINSIN and Dr. Ir. Anselme ADEGBIDI - 2006 (December): Engineer degree (Ir.) with Best Distinction, Agricultural Economics, Université d’Abomey Calavi, Bénin; Advisors: Prof. Dr. Ir. Gauthier BIAOU and Dr. Aliou DIAGNE - 2005 (August): Bachelor in General Agronomy, Université d’Abomey Calavi, Bénin - 2001 (July): Baccalauréat (Mathematical and Physical Sciences), Lycée TOFFA I (Benin). RESEARCH AND PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCES - 2016-2019 (on going): Assistant Professor and Senior Researcher in ASE (African School of Economics). - 2016 (March-August): Consultancy works in ICRISAT (International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics), Bamako, Mali, Impact Evaluation of agricultural policy. - 2013- 2016: PhD student (WASCAL), Research project: Modelling the livelihood of farmers subject to extreme events: Case study of flooding in Benin, Supervisor: Pr Adama DIAW (University Gaston Berger, Senegal) and Dr. Tobias Wunscher (ZEF, University of Bonn, Germany). - 04/2010 - 12/2010: Consultancy works in AfricaRice (Center of Rice for Africa) Impact Evaluation of agricultural technology. - 01/2007 – 01/2008: DEA Student, Natural Resources Management, University of Abomey Calavi, Benin, Supervisor Prof. Dr. Ir. Brice Sinsin; Research project: Estimating the economic value of Non Timber Forest Product (NTFP) in Sampéto (Banikoara District). 1 - 06/2006 – 12/2006: Engineer degree Student, Agricultural economics, University of Abomey Calavi, Benin, Supervisor Prof. -

Rôles Et Normes De Genre Dans La Production, La Consommation Et La Santé Au Bénin

Conseil de l'Alimentation et de la Nutrition du Bénin Secrétariat Permanent PROJET MULTISECTORIEL DE L’ALIMENTATION, DE LA SANTE ET DE LA NUTRITION Rôles et normes de genre dans la production, la consommation et la santé au Bénin Cas des communes de Bonou, Boukoumbé, Lalo, Ouéssè et Zê RAPPORT FINAL Mars 2016 Conseil de l'Alimentation et de la Nutrition du Bénin Secrétariat Permanent PROJET MULTISECTORIEL DE L’ALIMENTATION, DE LA SANTE ET DE LA NUTRITION (PMASN) (P143652) Rôles et normes de genre dans la production, la consommation et la santé au Bénin Cas des communes de Bonou, Boukoumbé, Lalo, Ouéssè et Zê RAPPORT Mars 2016 Noroarisoa Ravaozanany Nadia Fanou Fogny Andrianasolo Ratsimatahotrarivo Rita Ogbou Abou Josephine Razafindrasoa Alida Adjile Prosper Baloïtcha Gagnin Dohou Florian Fadonougbo Jemima Gbego Romule Gbodja Alphonse Kpangon Indira Nonfon Sous la coordination du Professeur Roch L. Mongbo, Secrétaire Permanent du Conseil de l’Alimentation et de la Nutrition, Et du Professeur Léopold Fakambi Les observations, interprétations et opinions qui sont exprimées dans ce rapport ne reflètent pas nécessairement celles de la Banque Mondiale. Remerciements Ce rapport est le fruit d’une initiative que le Professeur Roch L. Mongbo, Secrétaire Permanent du Conseil de l’Alimentation et de la Nutrition (CAN) a lancée, avec l’appui de Menno Mulder-Sibanda, Senior Nutrition Specialist de la Banque Mondiale. Tout au long des différentes étapes du travail, ils ont donné des directives, observations et suggestions avisées. Noroarisoa Ravaozanany a dirigé l’ensemble des travaux avec Nadia Fanou Fogny, l’analyse des données et la rédaction ayant tiré profit des contributions substantielles de Andrianasolo Ratsimatahotrarivo et Joséphine Razafindrasoa. -

Benin• Floods Rapport De Situation #13 13 Au 30 Décembre 2010

Benin• Floods Rapport de Situation #13 13 au 30 décembre 2010 Ce rapport a été publié par UNOCHA Bénin. Il couvre la période du 13 au 30 Décembre. I. Evénements clés Le PDNA Team a organisé un atelier de consolidation et de finalisation des rapports sectoriels Le Gouvernement de la République d’Israël a fait don d’un lot de médicaments aux sinistrés des inondations La révision des fiches de projets du EHAP a démarré dans tous les clusters L’Organisation Ouest Africaine de la Santé à fait don d’un chèque de 25 millions de Francs CFA pour venir en aide aux sinistrés des inondations au Bénin L’ONG béninoise ALCRER a fait don de 500.000 F CFA pour venir en aide aux sinistrés des inondations 4 nouveaux cas de choléra ont été détectés à Cotonou II. Contexte Les eaux se retirent de plus en plus et les populations sinistrés manifestent de moins en moins le besoin d’installation sur les sites de déplacés. Ceux qui retournent dans leurs maisons expriment des besoins de tentes individuelles à installer près de leurs habitations ; une demande appuyée par les autorités locales. La veille sanitaire post inondation se poursuit, mais elle est handicapée par la grève du personnel de santé et les lots de médicaments pré positionnés par le cluster Santé n’arrivent pas à atteindre les bénéficiaires. Des brigades sanitaires sont provisoirement mises en place pour faire face à cette situation. La révision des projets de l’EHAP est en cours dans les 8 clusters et le Post Disaster Needs Assessment Team est en train de finaliser les rapports sectoriels des missions d’évaluation sur le terrain dans le cadre de l’élaboration du plan de relèvement. -

BENIN FY2020 Annual Work Plan

USAID’s Act to End NTDs | West Benin FY20 WORK PLAN USAID’s Act to End Neglected Tropical Diseases | West Program BENIN FY2020 Annual Work Plan Annual Work Plan October 1, 2019 to September 30, 2020 1 USAID’s Act to End NTDs | West Benin FY20 WORK PLAN Contents ACRONYM LIST ............................................................................................................................................... 3 NARRATIVE ..................................................................................................................................................... 6 1. National NTD Program Overview....................................................................................................... 6 2. IR1 PLANNED ACTIVITIES: LF, TRA, OV ............................................................................................... 8 i. Lymphatic Filariasis ........................................................................................................................ 8 ii. Trachoma ..................................................................................................................................... 12 iii. Onchocerciasis ............................................................................................................................. 14 3. SUSTAINABILITY STRATEGY ACTIVITIES (IR2 and IR3) ...................................................................... 16 i. DATA SECURITY AND MANAGEMENT .......................................................................................... 16 ii. -

BENIN-2 Cle0aea97-1.Pdf

1° vers vers BOTOU 2° vers NIAMEY vers BIRNIN-GAOURÉ vers DOSSO v. DIOUNDIOU vers SOKOTO vers BIRNIN KEBBI KANTCHARI D 4° G vers SOKOTO vers GUSAU vers KONTAGORA I E a BÉNIN N l LA TAPOA N R l Pékinga I o G l KALGO ER M Rapides a vers BOGANDÉ o Gorges de de u JE r GA Ta Barou i poa la Mékrou KOULOU Kompa FADA- BUNZA NGOURMA DIAPAGA PARC 276 Karimama 12° 12° NATIONAL S o B U R K I N A GAYA k o TANSARGA t U DU W o O R Malanville KAMBA K Ka I bin S D É DU NIGER o ul o M k R G in u a O Garou g bo LOGOBOU Chutes p Guéné o do K IB u u de Koudou L 161 go A ZONE vers OUAGADOUGOU a ti r Kandéro CYNÉGÉTIQUE ARLI u o KOMBONGOU DE DJONA Kassa K Goungoun S o t Donou Béni a KOKO RI Founougo 309 JA a N D 324 r IG N a E E Kérémou Angaradébou W R P u Sein PAMA o PARC 423 ZONE r Cascades k Banikoara NATIONAL CYNÉGÉTIQUE é de Sosso A A M Rapides Kandi DE LA PENDJARI DE L'ATAKORA Saa R Goumon Lougou O Donwari u O 304 KOMPIENGA a Porga l é M K i r A L I B O R I 11° a a ti A j 11° g abi d Gbéssé o ZONE Y T n Firou Borodarou 124 u Batia e Boukoubrou ouli A P B KONKWESSO CYNÉGÉTIQUE ' Ségbana L Gogounou MANDOURI DE LA Kérou Bagou Dassari Tanougou Nassoukou Sokotindji PENDJARI è Gouandé Cascades Brignamaro Libant ROFIA Tiélé Ede Tanougou I NAKI-EST Kédékou Sori Matéri D 513 ri Sota bo li vers DAPAONG R Monrou Tanguiéta A T A K O A A é E Guilmaro n O Toukountouna i KARENGI TI s Basso N è s u Gbéroubou Gnémasson a Î o u è è è É S k r T SANSANN - g Kouarfa o Gawézi GANDO Kobli A a r Gamia MANGO Datori m Kouandé é Dounkassa BABANA NAMONI H u u Manta o o Guéssébani -

Institut National Des Recherch Ational Des Recherches Agricoles Du Bénin (IN Gricoles Du Bénin (INRAB)

Sixième article : Disponibilité foncière et productions végétales dans la commune de Bonou au sud -est du Bénin Par : C. C. GNIMADI, D. M. TOFFI, N. R. AHOYO ADJOVI et E. AHO Pages (pp.) 56-70. Bulletin de la Recherche Agronomique du Bénin (BRAB) Numéro Spécial Développement Agricole Durable (DAD) – Décembre 2017 Le BRAB est en ligne (on line) sur le s sites web http://www.slire.net & http://www.inrab.org ISSN sur papier (on hard copy) : 1025-2355 et ISSN en ligne (on line) : 1840-7099 Bibliothèque Nationale (BN) du Bénin Institut National des Recherches Agricoles du Bénin (INRAB) Centre de Recherches Agricoles à vocation nationale basé à Agonkanmey (CRA -Agonkanmey) Programm e Informati on Scientifique et Biométrie (PIS -B) 01 BP 884 Recette Principale, Cotonou 01 - République du Bénin Tél.: (229) 21 30 02 64 / 21 13 38 70 / 21 03 40 59 ; E-mail : [email protected] / [email protected] 1 Bulletin de la Recherche Agronomique du Bénin (BRAB) Numéro Spécial Développement Agricole Durable (DAD) – Décembre 2017 BRAB en ligne (on line) sur les sites web http://www.slire.net & http://www.inrab.org ISSN sur papier (on hard copy) : 1025 -2355 et ISSN en ligne (on line) : 1840 -7099 Disponibilité foncière et productions végétales dans la commune de Bonou au sud-est du Bénin C. C. GNIMADI 9, D. M. TOFFI 9, N. R. AHOYO ADJOVI 10 et E. AHO 11 Résumé Support de la production agricole, le foncier joue un rôle essentiel dans les activités agricoles. L’objectif de l’étude était d’analyser les nouvelles distributions de la terre à la fonction agricole par la taille et le type de culture. -

Partner Country Coverage

IMaD’s Lessons Learned Luis Benavente MD, MS CORE’s webinar August 29, 2012 Insert title here Country Number of health Health workers trained in topics related to malaria diagnosis as of June 2012 total N facility visits trained Baseline Outreach How to TOT and On-the- job Database National External Malaria all assesmt. of training & perform supervi- training data entry, Malaria competency micros- Diagnostic support laboratory sors during mainte- Slide sets, assess- copy and capabilities supervision assessments OTSS OTSS nance NAMS ments RDTs Angola 5 6 2 18 12 0 0 12 26 70 Benin 11 409 2 30 1671 9 0 0 40 1,752 Burundi 18 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 DR Congo 0 0 0 23 0 0 0 0 74 97 Ethiopia 4 0 4 0 0 0 13 17 0 34 Ghana 37 1109 37 46 3704 10 10 6 40 3,853 Guinea Con. 11 0 11 0 0 0 0 0 20 31 Kenya 1192 52 1192 66 312 0 0 37 67 1,674 Liberia 8 200 8 35 975 11 0 7 141 1,177 Madagascar 50 31 50 18 18 0 0 0 23 109 Malawi 14 521 14 75 1132 3 0 0 64 1,288 Mali 5 172 5 24 1188 4 0 0 40 1,261 Nigeria 40 0 0 0 0 0 0 26 0 26 Zambia 6 278 6 12 1733 5 0 9 92 1,857 Total 1,401 2,778 1,331 347 10,745 42 23 114 627 13,229 Proportion of febrile episodes caused by Plasmodium falciparum Source: d’Acremont V, Malaria Journal, 2010 Better testing is needed to assess the impact of malaria control interventions Parasitemia prevalence after IRS, countries with at least biennial monitoring 80% Namibia-C Zimbabwe Moz-Maputo 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% 1948 1950 1952 1954 1956 1958 1960 1962 1964 1966 1968 CORE’s Surviving Malaria Pathway ITNs - Bednet use Caretaker recognizes -

Download the Success Story

SUCCESS STORY THE INTEGRATED HEALTH SERVICES ACTIVITY (IHSA) Supporting integrated care for survivors of gender-based violence with a virtual One Stop GBV center In Benin, gender-based violence (GBV) survivors can access an integrated package of services, including medical and psychosocial care, by visiting one of the country’s One Stop GBV centers, located in the cities of Cotonou, Parakou, and Abomey. However, GBV survivors who live in other regions might be unable to access these services due to financial and other barriers. To address this gap and increasing GBV survivors’ access to care, the Direction de la Santé de la Mère et de l’Enfant (DSME), with technical input from IHSA, developed a model to provide integrated care for GBV survivors in areas not covered by the three existing One Stop centers. Through a pilot project in the department of Ouémé as a precursor to nationwide implementation, IHSA helped to create and launch the first virtual One Stop GBV center, which is hosted in a regular health facility and equipped to provide prevention, treatment, and psychosocial support services to clients. The virtual center complies with GBV protocols, including client confidentiality. The integrated package of services, identical to the one provided at the One Stop GBV center, is provided to survivors by general practitioners trained by IHSA on GBV case management in accordance with national guidelines. Implementation and stakeholder training As a first step, and with technical input from IHSA, the DSME developed a concept note describing the approach and the methodology of the virtual One Stop center, which was validated during a multi-stakeholder workshop on April 12, 2019. -

Journal of Experimental Biology and Agricultural Sciences, June - 2017; Volume – 5(3) 327 LAWANI Rebecca Annick Niréti

Journal of Experimental Biology and Agricultural Sciences, June - 2017; Volume – 5(3) 327 LAWANI Rebecca Annick Niréti Journal of Experimental Biology and Agricultural Sciences http://www.jebas.org ISSN No. 2320 – 8694 CHARACTERIZATION OF FARMERS’ CROPPING SYSTEMS IN THREE DISTRICTS (BONOU, OUINHI, ZAGNANADO) OF BENIN REPUBLIC LAWANI Rebecca Annick Niréti1*, KELOME Nelly Carine2, AGASSOUNON DJIKPO TCHIBOZO Micheline3, HOUNKPE Jechonias2 1University of Abomey-Calavi, National Institute of Water, Laboratory of Applied Hydrology (LHA), 01 BP 1950 Abomey -Calavi (B enin) 2University of Abomey-Calavi, Faculty of Sciences and Techniques, Department of Earth Sciences, Laboratory of Geology, Mines and Environment (LaboGME), BP: 01 BP 526 Cotonou (Benin) 3University of Abomey-C alavi, Faculty of Science and Techniques, Department of Genetics and Biotechnology, Laboratory of Standards, Microbiological Quali ty Control, Nutrition and Pharmacology (LNCQMNP), 01 BP1636 RP Cotonou (Benin) Received – March 05, 2017; Revision – April 24, 2017; Accepted – June 19, 2017 Available Available Online – June 30, 2017 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18006/2017.5(3).321.331 ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Objective of this study was to understand farmer’s management practices related to water quality and sanitary Agricultural Practices issue in order to assess the risks of these practices especially in the Upper Ouémé Delta. All the data related to Crops this investigation were collected by field observations, interviews, surveys of farming households and focus groups. The surveys were conducted with 387 farmers belongs to three districts of southern Benin (Bonou, Fertilizers Ouinhi, and Zagnanado). Results of study revealed that 97.48%, 57.78%, 76% of farmers respectively of the Bonou, Ouinhi, and Zagnanado districts grow food crops. -

Nigeria Benin Togo Burkina Faso Niger Ghana

! 1°E 2°E 3°E 4°E 5°E 6°E! ! ! ! MA-024 !Boulgou !Kantchari Gwadu Birnin-Kebbi ! Tambawel Matiacoali ! ! Pekinga Aliero ! ! ! A f r i c a Jega Niger ! Gunmi ! Anka Diapaga Koulou Birnin Tudu B! enin ! Karimam!a Bunza ! ! ! N N ° ° 2 Zugu 2 1 ! 1 Gaya Kamba ! Karimama Malanville ! ! Atlantic Burkina Faso Guéné ! Ocean Kombongou ! Dakingari Fokku ! Malanville ! ! Aljenaari ! Arli Mahuta ! ! Founougo ! Zuru Angaradébou ! ! Wasagu Kérémou Koko ! ! Banikoara ! Bagudo Banikoara ! ! ! Kaoje ! Duku Kandi ! Kandi ! Batia Rijau ! ! Porga N ! N ° Tanguieta ° 1 1 1 Ségbana 1 Kerou ! Yelwa Mandouri Segbana ! ! Konkwesso Ukata ! ! Kérou Gogounou Gouandé ! ! Bin-Yauri ! Materi ! ! Agwarra Materi Gogounou ! Kouté Tanguieta ! ! Anaba Gbéroubouè ! ! Ibeto Udara Toukountouna ! ! Cobly !Toukountouna Babana Kouande ! Kontagora Sinendé Kainji Reservoir ! ! Dounkassa Natitingou Kouandé ! Kalale ! ! Kalalé ! ! Bouka Bembereke ! Boukoumbe Natitingou Pehunko Sinende ! Kagara Bembèrèkè Auna ! ! Boukoumbé ! Tegina ! N N ° ° 0 Kandé 0 ! Birni ! 1 ! 1 ! Wawa Ndali Nikki ! ! New Bussa ! Kopargo Zungeru !Kopargo ! Kizhi Niamtougou Ndali ! Pizhi ! Djougou Yashikera ! ! Ouaké ! ! Pagoud!a Pya ! Eban ! Djougou Kaiama ! Guinagourou Kosubosu ! Kara ! ! ! Ouake Benin Perere Kutiwengi ! Kabou ! Bafilo Alédjo Parakou ! ! ! Okuta Parakou ! Mokwa Bassar ! Kudu ! ! Pénessoulou Jebba Reservoir ! Bétérou Kutigi ! ! ! Tchaourou Bida Kishi ! ! ! Tchamba ! Dassa ! Bassila Sinou 2°E ! ! Nigeria ! N N Sokodé ° ° ! Save 9 9 Bassila Savalou Bode-Sadu !Paouignan Tchaourou Ilesha Ibariba