Benin Private Health Sector Census

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palace Sculptures of Abomey

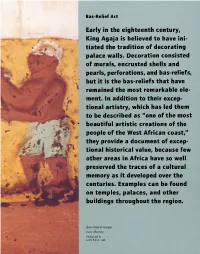

Bas-Relief Art Early in the eighteenth century, King Agaja is believed to have ini tiated the tradition of decorating palace walls. Decoration consisted of murals, encrusted shells and pearls, perfo rations, and bas-reliefs, , but it is the bas-reliefs that have remained the most remarkable ele ment. In addition to their excep tional artistry, which has led them to be described as "one of the most " beautiful artistic creations of the people of the West African coast, rr they provide a document of excep tional historical value, because few other areas in Africa have so well preserved the traces of a cultural · . memory as it developed over the centuries. Exa mples can be found on temples, palaces, and other buildings throughout the region. Bas-relief at temple near Abomey. Photograph by Leslie Railler, 1996. BAS-RELIEF ART 49 Commonly called noudide in Fon, from the root word meaning "to design" or "to portray," the bas-reliefs are three-dimensional, modeled- and painted earth pictograms. Early examples of the form, first in religious temples and then in the palaces, were more abstract than figurative. Gradually, figurative depictions became the prevalent style, illustrating the tales told by the kings' heralds and other Fon storytellers. Palace bas-reliefs were fashioned according to a long-standing tradition of The original earth architectural and sculptural renovation. used to make bas Ruling monarchs commissioned new palaces reliefs came from ter and artworks, as well as alterations of ear mite mounds such as lier ones, thereby glorifying the past while this one near Abomey. bringing its art and architecture up to date. -

Pdf | 857.14 Kb

West and Central Africa Regional Office Humanitarian Situation Report © © UNICEF/UN0452608/Dejongh Reporting Period: 1 January to 30 June 2021 Highlights Situation in Numbers • Several countries in West and Central Africa have entered a third wave of the COVID-19 pandemic with case numbers rising to their highest levels 57 million since the start of the outbreak. Continued disruptions to essential services children in need of remain a challenge. humanitarian assistance in • Supporting the continuation of nutrition services in the context of COVID- WCAR (2021 OCHA HNO/HRP of 8 19 remains difficult, as COVID-19 has created barriers to community- countries and 2021 UNICEF HAC for 12 based activities carried out by Community Health Workers including early countries) SAM screening and prevention activities for Infant and Young Child Feeding (IYCF). • Schools have re-opened with many countries offering catch up classes to 350,820 student over the summer. UNICEF continues to scale-up WASH in new COVID-19 cases from schools to promote good health and hygiene. January to June 2021 (two- fold increase) in WCAR • Following the declaration of an Ebola outbreak in Guinea, UNICEF stepped up preparedness activities in six neighbouring countries (Cote 1.4% case fatality rate in d'Ivoire, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, and Senegal), where WCAR (consolidated data from approximately 40 million people under 18 years of age were at risk. On 19 WHO, MoH as of 30 June) June 2021 Guinea was officially declared Ebola-Free. • The security context has further deteriorated in the first six months of UNICEF Appeal 2021 2021. -

B E N I N Benin

Birnin o Kebbi !( !( Kardi KANTCHARIKantchari !( !( Pékinga Niger Jega !( Diapaga FADA N'GOUMA o !( (! Fada Ngourma Gaya !( o TENKODOGO !( Guéné !( Madécali Tenkodogo !( Burkina Faso Tou l ou a (! Kende !( Founogo !( Alibori Gogue Kpara !( Bahindi !( TUGA Suroko o AIRSTRIP !( !( !( Yaobérégou Banikoara KANDI o o Koabagou !( PORGA !( Firou Boukoubrou !(Séozanbiani Batia !( !( Loaka !( Nansougou !( !( Simpassou !( Kankohoum-Dassari Tian Wassaka !( Kérou Hirou !( !( Nassoukou Diadia (! Tel e !( !( Tankonga Bin Kébérou !( Yauri Atakora !( Kpan Tanguiéta !( !( Daro-Tempobré Dammbouti !( !( !( Koyadi Guilmaro !( Gambaga Outianhou !( !( !( Borogou !( Tounkountouna Cabare Kountouri Datori !( !( Sécougourou Manta !( !( NATITINGOU o !( BEMBEREKE !( !( Kouandé o Sagbiabou Natitingou Kotoponga !(Makrou Gurai !( Bérasson !( !( Boukombé Niaro Naboulgou !( !( !( Nasso !( !( Kounounko Gbangbanrou !( Baré Borgou !( Nikki Wawa Nambiri Biro !( !( !( !( o !( !( Daroukparou KAINJI Copargo Péréré !( Chin NIAMTOUGOU(!o !( DJOUGOUo Djougou Benin !( Guerin-Kouka !( Babiré !( Afekaul Miassi !( !( !( !( Kounakouro Sheshe !( !( !( Partago Alafiarou Lama-Kara Sece Demon !( !( o Yendi (! Dabogou !( PARAKOU YENDI o !( Donga Aledjo-Koura !( Salamanga Yérémarou Bassari !( !( Jebba Tindou Kishi !( !( !( Sokodé Bassila !( Igbéré Ghana (! !( Tchaourou !( !(Olougbé Shaki Togo !( Nigeria !( !( Dadjo Kilibo Ilorin Ouessé Kalande !( !( !( Diagbalo Banté !( ILORIN (!o !( Kaboua Ajasse Akalanpa !( !( !( Ogbomosho Collines !( Offa !( SAVE Savé !( Koutago o !( Okio Ila Doumé !( -

SUN Countries Deep-Dives Final Report Scaling up Nutrition Movement In-Depth Country Studies

SUN Countries deep-dives final report Scaling Up Nutrition Movement In-depth Country Studies Annex No 4 – List of interviews and group discussions per country Benin National level interviews were not carried out due to a clash with other SUN Movement Study happening during the same time. However, some information was collected through a group discussion with United Nations representatives. At subnational level information was collected in two municipalities through 10 interviews to government officers (7), and civil society representatives (3); and 3 group discussions that included 17 people participating from government (12), civil society (1). National level • Group discussion with four United Nations Representatives from UNICEF, World Food Program WFP and World Health Organization WHO. Subnational level Group discussions: • Members of the decentralised Multi-Stakeholder Platform (Cadre de Concertation Communal, CCC) of Adja Ouèrè. • Members of the decentralised Multi-Stakeholder Platform (Cadre de Concertation Communal, CCC) of Malanville. • With donor representatives from members of the decentralised Multi-Stakeholder Platform (Cadre de Concertation Communal, CCC) of Adja Ouèrè. Interviews carried out in Adja Ouèrè, Plateau Department: • Head of Planification, Nutrition Focal Point, Adja Ouere Commune. • Regional Coordinator of the Permanent Secretariat of the food and nutrition Council, SP- CAN Ouémé / Plateau. • Two Representatives of the Groupe d'action pour le bien-être familial (GABF), implementing NGOs of the Multisectoral Food, Health and Nutrition Project, PMASN Project. Civil Society Organisation. Interviews carried out in Malanville, Alibori Department: • Two representatives from devolved services from social affairs and from the local authorities. Government. • Representative of the Bach Consulting for Development BCD, implementing NGO of the Multisectoral Food, Health and Nutrition Project, PMASN Project. -

GIEWS Country Brief Benin

GIEWS Country Brief Benin Reference Date: 23-April-2020 FOOD SECURITY SNAPSHOT Planting of 2020 main season maize ongoing in south under normal moisture conditions Above-average 2019 cereal crop harvested Prices of coarse grains overall stable in March Pockets of food insecurity persist Start of 2020 cropping season in south follows timely onset of rains Following the timely onset of seasonal rains in the south, planting of yams was completed in March, while planting of the main season maize crop is ongoing and will be completed by the end of April. The harvest of yams is expected to start in July, while harvesting operations of maize will start in August. Planting of rice crops, to be harvested from August, is underway. The cumulative rainfall amounts since early March have been average to above average in most planted areas and supported the development of yams and maize crops, which are at sprouting, seedling and tillering stages. Weeding activities are normally taking place in most cropped areas. In the north, seasonal dry weather conditions are still prevailing and planting operations for millet and sorghum, to be harvested from October, are expected to begin in May-June with the onset of the rains. In April, despite the ongoing pastoral lean season, forage availability was overall satisfactory in the main grazing areas of the country. The seasonal movement of domestic livestock, returning from the south to the north, started in early March following the normal onset of the rains in the south. The animal health situation is generally good and stable, with just some localized outbreaks of seasonal diseases, including Trypanosomiasis and Contagious Bovine Peripneumonia. -

S a Rd in Ia

M. Mandarino/Istituto Euromediterraneo, Tempio Pausania (Sardinia) Land07-1Book 1.indb 97 12-07-2007 16:30:59 Demarcation conflicts within and between communities in Benin: identity withdrawals and contested co-existence African urban development policy in the 1990s focused on raising municipal income from land. Population growth and a neoliberal environment weakened the control of clans and lineages over urban land ownership to the advantage of individuals, but without eradicating the importance of personal relationships in land transactions or of clans and lineages in the political structuring of urban space. The result, especially in rural peripheries, has been an increase in land aspirations and disputes and in their social costs, even in districts with the same territorial control and/or the same lines of nobility. Some authors view this simply as land “problems” and not as conflicts pitting locals against outsiders and degenerating into outright clashes. However, decentralization gives new dimensions to such problems and is the backdrop for clashes between differing perceptions of territorial control. This article looks at the ethnographic features of some of these clashes in the Dahoman historic region of lower Benin, where boundaries are disputed in a context of poorly managed urban development. Such disputes stem from land registries of the previous but surviving royal administration, against which the fragile institutions of the modern state seem to be poorly equipped. More than a simple problem of land tenure, these disputes express an internal rejection of the legitimacy of the state to engage in spatial structuring based on an ideal of co-existence; a contestation that is put forward with the de facto complicity of those acting on behalf of the state. -

Carte Pédologique De Reconnaissance De La République Populaire Du Bénin À 1/200.000 : Feuille De Djougou

P. FAURE NOTICE EXPLICATIVE No 66 (4) CARTE PEDOLOGIQUE DE RECONNAISSANCE de la République Populaire du Bénin à 1/200.000 Feuille de DJOUGOU OFFICE OE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIWE ET TECHNIOUE OUTRE-MER 1 PARIS 1977 NOTICE EXPLICATIVE No 66 (4) CARTE PEDOLOGIQUE DE RECONNAISSANCE de la RepubliquePopulaire du Bénin à 1 /200.000 Feuille de DJOUGOU P. FAURE ORSTOM PARIS 1977 @ORSTOM 2977 ISBN 2-7099-0423-3(édition cornpl8te) ISBN 2-7099-0433-0 SOMMAI RE l. l INTRODUCTION ........................................ 1 I .GENERALITES SUR LE MILIEU ET LA PEDOGENESE ........... 3 Localisationgéographique ............................ 3 Les conditionsde milieu 1. Le climat ................... 3 2 . La végétation ................. 6 3 . Le modelé et l'hydrographie ....... 8 4 . Le substratum géologique ........ 10 Les matériaux originels et la pédogenèse .................. 12 1 . Les matériaux originels .......... 12 2 . Les processus pédogénétiques ...... 13 II-LESSOLS .......................................... 17 Classification 1. Principes de classification ....... 17 2 . La légende .................. 18 Etudemonographique 1 . Les sols minérauxbruts ......... 20 2 . Les sois peuévolués ............ 21 3 . Les sols ferrugineuxtropicaux ....... 21 4 . Les sols ferraliitiques ........... 38 CONCLUSION .......................................... 43 Répartitiondes' sols . Importance relative . Critèresd'utilisation . 43 Les principalescontraintes pour la mise en valeur ............ 46 BIBLIOGRAPHIE ........................................ 49 1 INTRODUCTION La carte pédologique de reconnaissance à 1/200 000, feuille DJOUGOU, fait partie d'un ensemble de neuf coupures imprimées couvrant la totalité du terri- toire de la République Populaire du Bénin. Les travaux de terrain de la couverture générale ont été effectués de 1967 à 1971 par les quatre pédologues de la Section de Pédologie du Centre O. R.S. T.O.M. de Cotonou : D. DUBROEUCQ, P. FAURE, M. VIENNOT, B. -

Projet De Vulgarisation De L'aquaculture Continentale En République Du Bénin Quatrième Session Ordinaire Du Comité De Suiv

Projet de Vulgarisation de l’Aquaculture Continentale en République du Bénin Bureau du Projet / Direction des Pêches Tel: 21 37 73 47 No 004 Le 22 Juillet 2011 Email: [email protected] Un an après son démarrage en juin 2011, le Projet de Vulgarisation de l’Aquaculture Continentale en République du Bénin (PROVAC), a connu un bilan positif meublé d’activités diverses mais essentiellement axées sur les formations de pisciculteurs ordinaires par l’approche « fermier à fermier »démarré au début du mois de juin 2010, poursuit ses activités et vient d’amor‐ cer le neuvième mois de sa mise en œuvre. Quatrième session ordinaire du Comité de Suivi Le Mercredi 18 Mai 2011 s’est tenue, dans la salle de formation de la Direction des Pêches à Cotonou, la quatrième session ordinaire du Comité de Suivi du Projet de Vulgarisation de l’Aqua‐ culture Continentale en République du Bénin (PROVAC). Cette rencontre a connu la participation des membres du Comité de Suivi désignés par les quatre Centres Régionaux pour la Promotion Agricole (CeRPA) impliqués dans le Projet sur le terrain et a été rehaussée par la présence de la Représentante Résidente de la JICA au Bénin. A cette session, les CeRPA Ouémé/Plateau, Atlantique/Littoral, Zou/Collines et Mono/Couffo ont fait le point des activités du Projet sur le terrain, d’une part, et le Plan de Travail Annuel (PTA) 4e session ordinaire approuvé à Tokyo par la JICA au titre de l’année japonaise 2011 a été exposé, d’autre part, par le du Comité du Suivi Chef d’équipe des experts. -

The Geography of Welfare in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte D'ivoire, and Togo

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized The Geography of Welfare in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, and Togo Public Disclosure Authorized Nga Thi Viet Nguyen and Felipe F. Dizon Public Disclosure Authorized 00000_CVR_English.indd 1 12/6/17 2:29 PM November 2017 The Geography of Welfare in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, and Togo Nga Thi Viet Nguyen and Felipe F. Dizon 00000_Geography_Welfare-English.indd 1 11/29/17 3:34 PM Photo Credits Cover page (top): © Georges Tadonki Cover page (center): © Curt Carnemark/World Bank Cover page (bottom): © Curt Carnemark/World Bank Page 1: © Adrian Turner/Flickr Page 7: © Arne Hoel/World Bank Page 15: © Adrian Turner/Flickr Page 32: © Dominic Chavez/World Bank Page 48: © Arne Hoel/World Bank Page 56: © Ami Vitale/World Bank 00000_Geography_Welfare-English.indd 2 12/6/17 3:27 PM Acknowledgments This study was prepared by Nga Thi Viet Nguyen The team greatly benefited from the valuable and Felipe F. Dizon. Additional contributions were support and feedback of Félicien Accrombessy, made by Brian Blankespoor, Michael Norton, and Prosper R. Backiny-Yetna, Roy Katayama, Rose Irvin Rojas. Marina Tolchinsky provided valuable Mungai, and Kané Youssouf. The team also thanks research assistance. Administrative support by Erick Herman Abiassi, Kathleen Beegle, Benjamin Siele Shifferaw Ketema is gratefully acknowledged. Billard, Luc Christiaensen, Quy-Toan Do, Kristen Himelein, Johannes Hoogeveen, Aparajita Goyal, Overall guidance for this report was received from Jacques Morisset, Elisée Ouedraogo, and Ashesh Andrew L. Dabalen. Prasann for their discussion and comments. Joanne Gaskell, Ayah Mahgoub, and Aly Sanoh pro- vided detailed and careful peer review comments. -

Monographie Ketou

REPUBLIQUE DU BENIN =-=-=-=-=-=-=-==-=-=-= MINISTERE DE LA PROSPECTIVE, DU DEVELOPPEMENT ET DE L’EVALUATION DE L’ACTION PUBLIQUE (MPDEAP) -=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-= INSTITUT NATIONAL DE LA STATISTIQUE ET DE L’ANALYSE ECONOMIQUE (INSAE) -=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-= MONOGRAPHIE DE LA COMMUNE DE KETOU DIRECTION DES ETUDES DEMOGRAPHIQUES Décembre 2008 TABLE DES MATIERES LISTE DES TABLEAUX ............................................................................................................ vi LISTE DES GRAPHIQUES ........................................................................................................ x PREFACE ..................................................................................................................................... xi NOTE METHODOLOGIQUE SUR LE RGPH-3 .................................................................. xiii SITUATION GEOGRAPHIQUE DE KETOU DANS LE BENIN .......................................... 1 SITUATION GEOGRAPHIQUE DE LA COMMUNE DE KETOU DANS LE DEPARTEMENT DU PLATEAU ............................................................................................... 2 1- GENERALITES ........................................................................................................................ 3 1-1 Présentation de la commune .................................................................................................. 3 1-1-1 Le relief .......................................................................................................................... -

Emergency Plan of Action (Epoa) Benin: Ebola Virus Disease Preparedness

Emergency Plan of Action (EPoA) Benin: Ebola Virus Disease Preparedness DREF operation Operation n° MDRBJ014; Date of Issue: 27 August 2014 Glide ° Date of disaster: 20 July 2014 Operation start date: 25 August 2014 Operation end date: 27 November ( 3 months) Host National Society(ies): Benin Red Cross Society Operation budget: CHF 50,204 Number of people affected: 14 Zones at risk Number of people assisted: One Million (indirect) 141,299 (direct) N° of National Societies involved in the operation: International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, Luxembourg Red Cross and Netherlands Red Cross N° of other partner organizations involved in the operation: Ministry of Health, Ministry of the Interior (through the ANPC), Plan Benin and United Nations Children’s Fund A. Situation analysis Description of the disaster In February 2014, there was an outbreak of the Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) in Guinea, which has spread to Liberia, Mali, Nigeria, Senegal and Sierra Leone causing untold hardship and hundreds of deaths in these countries. As of 27 February 2015, a total of 23,694 cases, and 9,589 deaths, which were attributed to the EVD, had been recorded across the most affected countries of Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), an outbreak of the EVD was also reported, but is considered of a different origin than that which has affected West Africa. Benin, with a population of 10,051,000 (UNCDP 2014) shares a border with Nigeria, which has been affected by the EVD, and therefore the risks presented by the epidemic to the country are high. -

Disposal of Persistent Organic Pollutants and Obsolete Pesticides and Strengthening Life-Cycle Management of Pesticides in Benin”

Project evaluation series Mid-term evaluation of “Disposal of Persistent Organic Pollutants and Obsolete Pesticides and Strengthening Life-cycle Management of Pesticides in Benin” Project evaluation series Mid-term evaluation of “Disposal of persistent organic pollutants and obsolete pesticides and strengthening life-cycle management of pesticides in Benin” GCP/BEN/056/GFF FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2019 Required citation: FAO. 2019. Mid-term evaluation of “Disposal of Persistent Organic Pollutants and Obsolete Pesticides and Strengthening Life-cycle Management of Pesticides in Benin”. Rome. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. © FAO, 2019 Some rights reserved. This work is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo/legalcode/legalcode). Under the terms of this licence, this work may be copied, redistributed and adapted for non-commercial purposes, provided that the work is appropriately cited.