The Bible’ in Late Antiquity*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adult Sunday School Lesson Nassau Bay Baptist Church December 6, 2020

Adult Sunday School Lesson Nassau Bay Baptist Church December 6, 2020 In this beginning of the Gospel According to Luke, we learn why Luke wrote this account and to whom it was written. Then we learn about the birth of John the Baptist and the experience of his parents, Zacharias and Elizabeth. Read Luke 1:1-4 Luke tells us that many have tried to write a narrative of Jesus’ redemptive life, called a gospel. Attached to these notes is a list of gospels written.1 The dates of these gospels span from ancient to modern, and this list only includes those about which we know or which have survived the millennia. Canon The Canon of Scripture is the list of books that have been received as the text that was inspired by the Holy Spirit and given to the church by God. The New Testament canon was not “closed” officially until about A.D. 400, but the churches already long had focused on books that are now included in our New Testament. Time has proven the value of the Canon. Only four gospels made it into the New Testament Canon, but as Luke tells us, many others were written. Twenty-seven books total were “canonized” and became “canonical” in the New Testament. In the Old Testament, thirty-nine books are included as canonical. Canonical Standards Generally, three standards were held up for inclusion in the Canon. • Apostolicity—Written by an Apostle or very close associate to an Apostle. Luke was a close associate of Paul. • Orthodoxy—Does not contradict previously revealed Scripture, such as the Old Testament. -

Hidden Gospels. How the Search for Jesus Lost Its

HIDDEN GOSPELS This page intentionally left blank HIDDEN GOSPELS How the Search for Jesus Lost Its Way PHILIP JENKINS OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Oxford New York Auckland Bangkok Buenos Aires Cape Town Chennai Dares Salaam Delhi Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kolkata Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Sao Paulo Shanghai Taipei Tokyo Toronto Copyright © 2001 by Philip Jenkins First published by Oxford University Press, Inc., 2001 First issued as an Oxford University Press paperback, 2003 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication maybe reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jenkins, Philip, 1952- Hidden Gospels: how the search for Jesus lost its way/Philip Jenkins p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-19-515631-7(pbk.) 1. Apocryphal Gospels. 2. Christianity—Origin. I.Title. BS2851J462001 229.8—dc21 00-040641 Printed in the United States of America Contents Acknowledgments vii 1 Hiding and Seeking 3 2 Fragments of a Faith Forgotten 27 3 The First Gospels? Q and Thomas 54 4 Gospel Truth 82 5 Hiding Jesus: The Church and the Heretics 107 6 Daughters of Sophia 124 7 Into the Mainstream 148 8 The Gospels in the Media 178 9 The Next New Gospel 205 Notes 217 Index 249 This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgments I am grateful to Kathryn Hume and William Petersen for their always valuable advice; needless to say, they take no responsibil- ity for the arguments made here, nor for any errors of fact or faith. -

The Apostle Andrew Including Apelles, Aristobulus, Philologus and Stachys, of the Seventy

The Apostle Andrew Including Apelles, Aristobulus, Philologus and Stachys, of the Seventy November 30, 2016 The Calling of Andrew Andrew was born in Bethsaida, along with his brother Simon (Peter) and the Apostle Philip, of the Twelve (John 1:44). Andrew and Simon’s father, Jonah (Matthew 16:17), is never mentioned during the Gospel narratives. By contrast, James and John worked the fishing business with their father, Zebedee (Matthew 4:21). Some early accounts stated1 that Andrew and Simon were orphans, and that the fishing business, along with having bought their own boat (Luke 5:3), was a necessity for their support. Poverty and hard work were something that they had grown up with from childhood. Andrew had been a follower of John the Baptist, along with others of the Twelve and the Seventy. When John the Baptist pointed out Jesus, saying, “Behold the Lamb of God” (John 1:29, 36), immediately Andrew began to follow Jesus (John 1:37), but as a disciple, not as an Apostle. After this first calling, which occurred in early 27 AD, Andrew along with the others (Peter, James and John) were still part-time fishermen, but hadn’t been called to be Apostles yet. In late 27 AD, Jesus called them as Apostles, and they left everything to travel with Him full time (Matthew 4:20, 22). Shortly after that, they were sent to heal the sick, raise the dead, cleanse lepers and cast out demons by themselves (Matthew 10:1-8). A miracle was associated with this second calling (Luke 5:1-11). -

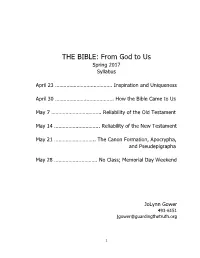

Syllabus and Text

THE BIBLE: From God to Us Spring 2017 Syllabus April 23 …………………………………. Inspiration and Uniqueness April 30 ………………….………………. How the Bible Came to Us May 7 …………………………….. Reliability of the Old Testament May 14 ………………………….. Reliability of the New Testament May 21 ……………………….. The Canon Formation, Apocrypha, and Pseudepigrapha May 28 ………………..………. No Class; Memorial Day Weekend JoLynn Gower 493-6151 [email protected] 1 INSPIRATION AND UNIQUENESS The Bible continues to be the best selling book in the World. But between 1997 and 2007, some speculate that Harry Potter might have surpassed the Bible in sales if it were not for the Gideons. This speaks to the world in which we now find ourselves. There is tremendous interest in things that are “spiritual” but much less interest in the true God revealed in the Bible. The Bible never tries to prove that God exists. He is everywhere assumed to be. Read Exodus 3:14 and write what you learn: ____________________________ _________________________________________________________________ The God who calls Himself “I AM” inspired a divinely authorized book. The process by which the book resulted is “God-breathed.” The Spirit moved men who wrote God-breathed words. Read the following verses and record your thoughts: 2 Timothy 3:16-17__________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________ Do a word study on “scripture” from the above passage, and write the results here: ____________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________ -

Canons of the New Testament

Canons of the New Testament Marcion Irenaeus Origen Eusebius Momsen List 140 CE - Rome 180 CE - Lyons 230 CE - Alexandria 325 CE - Rome 360 CE – St. Gall The Gospel Mark Matthew Matthew Matthew Galatians Luke Mark Mark Mark Corinthians Matthew Luke Luke John Romans John John John Luke Thessalonians Acts Acts Acts Romans Laodiceans Romans Romans Romans 1 Corinthians Colossians 1 Corinthians 1 Corinthians 1 Corinthians 2 Corinthians Philippians 2 Corinthians 2 Corinthians 2 Corinthians Galatians Philemon Galatians Galatians Galatians Ephesians Ephesians Ephesians Ephesians Philippians Philippians Philippians Philippians Colossians Colossians Colossians Colossians 1 Thessalonians 1 Thessalonians 1 Thessalonians 1 Thessalonians 2 Thessalonians 2 Thessalonians 2 Thessalonians 2 Thessalonians 1 Timothy 1 Timothy 1 Timothy 1 Timothy 2 Timothy 2 Timothy 2 Timothy 2 Timothy Titus Titus Titus Titus Philemon James (?) Philemon 1 Peter Acts 1 Peter 1 Peter 1 John Revelation of John 1 John 1 John 1 Clement 1 John Revelation of John Revelation of John Disputed Books 2 John Shepherd Hermas Hebrews 3 John Disputed Books James 1 Peter Hebrews 2 Peter 2 Peter 2 John II Peter 3 John II John Jude III John Revelation of John James Rejected Books Jude Gospel of Peter Epistle of Barnabas Acts of Peter Shepherd of Hermas Preaching of Peter Didache Revelation of Peter Gospel according to the Acts of Paul Shepherd of Hermas Hebrews Second Epistle of Clement Epistle of Barnabas Teachings of the Apostles Gospel of Thomas Gospel of Matthias Gospel of the Hebrews -

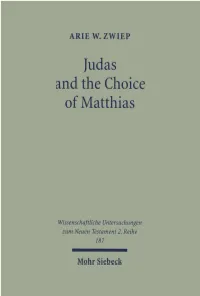

Judas and the Choice of Matthias. a Study on Context and Concern Of

Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament • 2. Reihe Herausgeber/Editor Jörg Frey Mitherausgeber / Associate Editors Friedrich Avemarie • Judith Gundry-Volf Martin Hengel • Otfried Hofius • Hans-Josef Klauck 187 Arie W. Zwiep Judas and the Choice of Matthias A Study on Context and Concern of Acts 1:15-26 Mohr Siebeck ARIE W. ZWIEP, born 1964; Ph.D. University of Durham; currently teaching New Testament at the Evangelische Theologische Hogeschool Ede (formerly Veenendaal) and the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. ISBN 3-16-148452-5 ISSN 0340-9570 (Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 2. Reihe) Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the Internet at http://dnb.ddb.de. © 2004 Mohr Siebeck Tübingen, Germany. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher's written permission. This applies particularly to reproductions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was printed by Druckpartner Rübelmann GmbH in Hemsbach on non-aging paper and bound by Buchbinderei Schaumann in Darmstadt. Printed in Germany. In Honour of My Doktorvater, James D. G. Dunn, Emeritus Professor of Divinity, University of Durham, On the Occasion of His 65 th Birthday Preface In this book I seek to determine the place of Judas Iscariot and his death in the Lukan writings, especially in the episode of the choice of his successor, Acts 1:15-26. It is in a sense to be regarded as a sequel to my Durham doctoral dissertation, The Ascension of the Messiah in Lukan Christology, in which I focused primarily on the first half of the opening chapter of Acts.1 For a number of years I have regarded the section now under investigation, the Judas-Matthias pericope, as one of the most tedious stories in the entire New Testament, an unhappy digression from the more spectacular events of Ascension and Pentecost. -

Apocrypha and Non-Canonical Writings

Apocrypha and non-Canonical Writings Contents Introduction ................................................. 2 Christian Canons .............................................. 2 “Our” Canon ............................................. 2 The Apocrypha ............................................... 3 The View of the Protestant Church .................................... 3 The Old Testament Apocrypha ...................................... 3 Character of the Books ........................................ 3 Historical Apocrypha ......................................... 3 The Legendary Apocrypha ..................................... 3 Apocalyptic Apocrypha ....................................... 3 Didactic Apocrypha ......................................... 4 Reasons for Rejecting the Old Testament Apocrypha ....................... 4 The New Testament Apocrypha ...................................... 5 Categories of the New Testament Apocrypha ........................... 5 Listing of New Testament Apocryphal books ........................... 5 The Pseudepigraphical Writings ...................................... 5 The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha ................................... 6 Apocalyptic Books .......................................... 6 Legendary Books ........................................... 6 Poetical Books ............................................ 6 Didactic (Teaching) Books ...................................... 6 The New Testament Pseudepigrapha ................................... 6 The pseudo-Gospels ........................................ -

The Authority of Scripture: How We Got the New Testament Mako A

The Authority of Scripture: How We Got the New Testament Mako A. Nagasawa, March 18, 2017 Contents Intro: Why Be Concerned? Part One: Criteria for Canonicity Part Two: The Canonical Gospels Part Three: The Gospel of Thomas Part Four: The Gospel of Judas Part Five: The Writing and Canonization of the New Testament Part Six: Discussing the New Testament Canon INTRODUCTION: WHY BE CONCERNED? Q: The DaVinci Code? The story where Jesus has a son by Mary Magdalene? Does Jesus have a skeleton or two in his closet? A: ??? Q: What about the Gospel of Thomas, which Elaine Pagels writes about? Or the Gospel of Judas, which is being ‘rediscovered’? A: ??? Q: Wasn’t the canon a conspiracy of the church hierarchy? A power move? A: ??? PART ONE: CRITERIA FOR CANONICITY 1. Authorship a. Who is supposed to have written this? And when? b. What evidence do we have for authorship? 2. Historical Use a. Did the Christian community broadly come to use this? b. Do we have physical manuscript evidence for it? c. Note: This is important because canonization was not a tops-down imposition achieved by power. Instead, it affirmed a bottoms-up recognition by the broader community, e.g. like a ‘Hall of Fame.’ 3. Content: a. Claim to fulfill the Old Testament story b. Jewish background, language, and ideas Jewish Cultural Assumptions Greco-Roman Cultural Assumptions Our physical bodies are good Physical bodies house the immortal soul, which wants to escape the body Expected ‘resurrection’ – the renewal of the Expected ‘disembodiment’ – the separation of physical world, including our bodies; God’s soul from body true humanity will be raised from the dead Caring for the poor is important Caring for the poor is not important since the body is not important Sexual ethics are important and are derived Have sex with anyone since the body is not from the Genesis creation story important (e.g. -

Early-Christian-Commentary-Sermon

“Here, in a single volume, are virtually all of the written insights on the Sermon on the Mount from those Christians who lived during the first few centuries after the apostles. I am particularly impressed by the thoroughness of Nesch’s research in gleaning these many quotations from the pre-Nicene Christians. This is a reference book that undoubtedly I will be using over and over again. In compiling this important work, Nesch has made a valuable contribution to the Kingdom of God.” – David Bercot, author of A Dictionary of Early Christian Beliefs, and Will the Real Heretics Please Stand Up “The Sermon on the Mount, Jesus' longest passage of teaching, has been beloved by Christians of all generations. But tragically, the interpretation of key portions of the Sermon on the Mount continues to divide the church today. The understanding of the early church has the potential to bring unity over what should be essential hallmarks of the Christian life. I commend Nesch's carefully researched volume to any who love Jesus' teaching and want to see His prayer for unity advanced.” – Finny Kuruvilla, author of King Jesus Claims His Church, and founder of Sattler College “Of many resources we can use to help us in our day, I believe this commentary will be greatly beneficial. It is not new theological ideas we need but to follow Christ and learn how. This volume brother Elliott has compiled will help us in our journey with the Lord.” – Greg Gordon, founder of SermonIndex.net, and author of The Following of Christ EARLY CHRISTIAN COMMENTARY of the SERMON on the MOUNT ELLIOTT NESCH, EDITOR Early Christian Commentary of the Sermon on the Mount. -

The Apostle Matthias

The Apostle Matthias August 9, 2014 GOSPEL: Luke 10:16-21 EPISTLE: Acts 1:12-17, 21-26 Matthias, the Oldest of the Twelve Apostles Matthias was born in Bethlehem1 of the Tribe of Judah, and was originally one of the Seventy. In his younger days, Matthias had been a student of Simeon2 the Host of God, who held the baby Jesus in his arms at the time of Mary’s purification (Luke 2:22-28), which was forty days after childbirth for a male child (Leviticus 12). Simeon prophesied at this time concerning both Jesus and Mary (Luke 2:33-35), and Simeon’s song of departure (i.e. death), called the Nunc Dimittis (Latin: let us depart), has been used as a dismissal in the Church ever since. Since Simeon died shortly after the birth of Christ, Matthias would have to be one of the older Apostles, and he would have been at least 20 years older than Jesus. Matthias’ age and maturity were probably a factor in his being proposed, along with Joseph called Barsabas, to replace Judas (Acts 1:23). Joseph Barsabas, also called Judah (Acts 15:22) and Justus (Acts 1:23), was Jesus’ older stepbrother, and was a prophet and one of the leading men among the Jerusalem Church in 48 AD at the Council of Jerusalem (Acts 15:22,32). Both men were among the oldest and most mature of the Seventy. As a student of Simeon, Matthias would have been very familiar with Simeon’s teaching and his hopes and dreams, which included “waiting for the Consolation of Israel” (Luke 2:25), meaning the Advent of the Messiah. -

Errors About the Old Testament Apocrypha

Chapter 1. Errors about the Old Testament Apocrypha Some people argue that what is known as “the Old Testament Apocrypha” should be regarded as being as part of God’s Holy Scriptures. These Apocryphal writings include Tobit, Judith, Additions to the Book of Esther, The Wisdom of Solomon, Sirach (Ecclesiasticus), Baruch (including the Letter of Jeremiah), Additions to the Book of Daniel (The Prayer of Azariah, The Song of the Three Young Men, Susanna, Bel and the Dragon), 1 Maccabees and 2 Macabees. 1 The above Apocryphal writings must be distinguished from what is called the New Testament Apocrypha. The New Testament Apocryphal writings include Protoevangelium Jacobi (or the so-called Gospel of James), Thomas Gospel of the Infancy, Gospel of Matthias, Gospel of Thomas, Gospel of Bartholomew, Gospel of the Hebrews, the Gospel of the Egyptians, History of Joseph the Carpenter, Acts of Peter, Acts of John, Acts of Thomas, Epistle of the Apostles, Apocalysis Beatae Mariae, Virginis de poenis and the Apocalypse of Paul. Almost all of those today who argue that the above Old Testament Apocryphal writings should be part of the Old Testament do not believe that these New Testament Apocryphal writings should be a part of the New Testament. A false argument One of the main arguments used by those who say we should accept the Old Testament Apocrypha as a part of the Old Testament is that certain church councils decided this should be so. As shown, however, by Chapter 4 “The Church – Highest Authority?” in my book “Highest Authority: Church, Scripture Or Tradition?”, such a reliance on the decisions of certain church councils is very unwise. -

Our Supreme Leader Christ – the Only Begotten Son Through the Holy Spirit Daughter the Leader and the “Underleader” of the Church on Earth

THE HEADSHIP AND PRIESTHOOD OF DEITY THE END OF ALL REPRESENTATIVE KINGSHIP AND PRIESTHOOD OF FALLEN MEN! THE REVELATION OF OUR SUPREME LEADER CHRIST – THE ONLY BEGOTTEN SON THROUGH THE HOLY SPIRIT DAUGHTER THE LEADER AND THE “UNDERLEADER” OF THE CHURCH ON EARTH. 1TG8:26 "No. 8" O jaded soul, So sated with Satanic myth, Sophistic lore, And vapid store; So deadly cloy'd With truth alloy'd; So spent, in sooth, For drossless truth-- Behold: the Bowl Of golden Oil (The Spirit's toil), And Stick, and Tree, or beacon Three—Affinity Of trinity, Divinity, Eternity! O Soul! Awake! Swing wide thy gate!--The King! He brings, in "No. 8," More butter from His kine and sheep; Yea, honey too! O soul, why sleep! Arouse thee from thy deathly swoon, And of the Holy Spirit's boon-- The rare, the fine, the large, the stern delight -- Let feast thy sicklied appetite!-- Behold: The "Hands", the "Sticks", the "Scroll", The "Stars," the "Lion," "Hour," and "Rod"-- The mystic "Seven" that unroll The crowning work on earth of God! Digest thou not this symbol' code? Make Present Truth thy lone abode, And gather up the victuals past, Then make ne'er more such light repast!-- Behold the woman starry crown'd; Herself in light resplendent gown'd Be thou one of this woman's seed, Thou must be true in word and deed. Behold, the locust come to see If victory's seal doth rest on thee, Lest soon the sting of scorpions tail Convulse thy soul and make thee quail With racking, lancinating pain To torment mad thy throbbing brain, Then heaven's horsemen tread thee down, Bereft of life's eternal crown! And under dank eroded sod, A thousand years thou lie a clod.