Introducing the Da Vinci Code

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adult Sunday School Lesson Nassau Bay Baptist Church December 6, 2020

Adult Sunday School Lesson Nassau Bay Baptist Church December 6, 2020 In this beginning of the Gospel According to Luke, we learn why Luke wrote this account and to whom it was written. Then we learn about the birth of John the Baptist and the experience of his parents, Zacharias and Elizabeth. Read Luke 1:1-4 Luke tells us that many have tried to write a narrative of Jesus’ redemptive life, called a gospel. Attached to these notes is a list of gospels written.1 The dates of these gospels span from ancient to modern, and this list only includes those about which we know or which have survived the millennia. Canon The Canon of Scripture is the list of books that have been received as the text that was inspired by the Holy Spirit and given to the church by God. The New Testament canon was not “closed” officially until about A.D. 400, but the churches already long had focused on books that are now included in our New Testament. Time has proven the value of the Canon. Only four gospels made it into the New Testament Canon, but as Luke tells us, many others were written. Twenty-seven books total were “canonized” and became “canonical” in the New Testament. In the Old Testament, thirty-nine books are included as canonical. Canonical Standards Generally, three standards were held up for inclusion in the Canon. • Apostolicity—Written by an Apostle or very close associate to an Apostle. Luke was a close associate of Paul. • Orthodoxy—Does not contradict previously revealed Scripture, such as the Old Testament. -

The Body/Soul Metaphor the Papal/Imperial Polemic On

THE BODY/SOUL METAPHOR THE PAPAL/IMPERIAL POLEMIC ON ELEVENTH CENTURY CHURCH REFORM by JAMES R. ROBERTS B.A., Catholic University of America, 1953 S.T.L., University of Sr. Thomas, Rome, 1957 J.C.B., Lateran University, Rome, 1961 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in » i THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September, 1977 Co) James R. Roberts, 1977 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 Date Index Chapter Page (Abst*ac't 'i Chronological list of authors examined vii Chapter One: The Background . 1 Chapter Two: The Eleventh Century Setting 47 Conclusion 76 Appendices 79 A: Excursus on Priestly Dignity and Authority vs Royal or Imperial Power 80 B: Excursus: The Gregorians' Defense of the Church's Necessity for Corporal Goods 87 Footnotes 92 ii ABSTRACT An interest in exploring the roots of the Gregorian reform of the Church in the eleventh century led to the reading of the polemical writings by means of which papalists and imperialists contended in the latter decades of the century. -

Download Ancient Apocryphal Gospels

MARKus BOcKMuEhL Ancient Apocryphal Gospels Interpretation Resources for the Use of Scripture in the Church BrockMuehl_Pages.indd 3 11/11/16 9:39 AM © 2017 Markus Bockmuehl First edition Published by Westminster John Knox Press Louisville, Kentucky 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26—10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the pub- lisher. For information, address Westminster John Knox Press, 100 Witherspoon Street, Louisville, Kentucky 40202- 1396. Or contact us online at www.wjkbooks.com. Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright © 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the U.S.A. and are used by permission. Map of Oxyrhynchus is printed with permission by Biblical Archaeology Review. Book design by Drew Stevens Cover design by designpointinc.com Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Bockmuehl, Markus N. A., author. Title: Ancient apocryphal gospels / Markus Bockmuehl. Description: Louisville, KY : Westminster John Knox Press, 2017. | Series: Interpretation: resources for the use of scripture in the church | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016032962 (print) | LCCN 2016044809 (ebook) | ISBN 9780664235895 (hbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781611646801 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Apocryphal Gospels—Criticism, interpretation, etc. | Apocryphal books (New Testament)—Criticism, interpretation, etc. Classification: LCC BS2851 .B63 2017 (print) | LCC BS2851 (ebook) | DDC 229/.8—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016032962 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48- 1992. -

Hidden Gospels. How the Search for Jesus Lost Its

HIDDEN GOSPELS This page intentionally left blank HIDDEN GOSPELS How the Search for Jesus Lost Its Way PHILIP JENKINS OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Oxford New York Auckland Bangkok Buenos Aires Cape Town Chennai Dares Salaam Delhi Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kolkata Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Sao Paulo Shanghai Taipei Tokyo Toronto Copyright © 2001 by Philip Jenkins First published by Oxford University Press, Inc., 2001 First issued as an Oxford University Press paperback, 2003 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication maybe reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jenkins, Philip, 1952- Hidden Gospels: how the search for Jesus lost its way/Philip Jenkins p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-19-515631-7(pbk.) 1. Apocryphal Gospels. 2. Christianity—Origin. I.Title. BS2851J462001 229.8—dc21 00-040641 Printed in the United States of America Contents Acknowledgments vii 1 Hiding and Seeking 3 2 Fragments of a Faith Forgotten 27 3 The First Gospels? Q and Thomas 54 4 Gospel Truth 82 5 Hiding Jesus: The Church and the Heretics 107 6 Daughters of Sophia 124 7 Into the Mainstream 148 8 The Gospels in the Media 178 9 The Next New Gospel 205 Notes 217 Index 249 This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgments I am grateful to Kathryn Hume and William Petersen for their always valuable advice; needless to say, they take no responsibil- ity for the arguments made here, nor for any errors of fact or faith. -

The Apostle Andrew Including Apelles, Aristobulus, Philologus and Stachys, of the Seventy

The Apostle Andrew Including Apelles, Aristobulus, Philologus and Stachys, of the Seventy November 30, 2016 The Calling of Andrew Andrew was born in Bethsaida, along with his brother Simon (Peter) and the Apostle Philip, of the Twelve (John 1:44). Andrew and Simon’s father, Jonah (Matthew 16:17), is never mentioned during the Gospel narratives. By contrast, James and John worked the fishing business with their father, Zebedee (Matthew 4:21). Some early accounts stated1 that Andrew and Simon were orphans, and that the fishing business, along with having bought their own boat (Luke 5:3), was a necessity for their support. Poverty and hard work were something that they had grown up with from childhood. Andrew had been a follower of John the Baptist, along with others of the Twelve and the Seventy. When John the Baptist pointed out Jesus, saying, “Behold the Lamb of God” (John 1:29, 36), immediately Andrew began to follow Jesus (John 1:37), but as a disciple, not as an Apostle. After this first calling, which occurred in early 27 AD, Andrew along with the others (Peter, James and John) were still part-time fishermen, but hadn’t been called to be Apostles yet. In late 27 AD, Jesus called them as Apostles, and they left everything to travel with Him full time (Matthew 4:20, 22). Shortly after that, they were sent to heal the sick, raise the dead, cleanse lepers and cast out demons by themselves (Matthew 10:1-8). A miracle was associated with this second calling (Luke 5:1-11). -

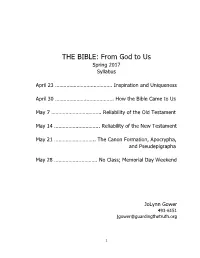

Syllabus and Text

THE BIBLE: From God to Us Spring 2017 Syllabus April 23 …………………………………. Inspiration and Uniqueness April 30 ………………….………………. How the Bible Came to Us May 7 …………………………….. Reliability of the Old Testament May 14 ………………………….. Reliability of the New Testament May 21 ……………………….. The Canon Formation, Apocrypha, and Pseudepigrapha May 28 ………………..………. No Class; Memorial Day Weekend JoLynn Gower 493-6151 [email protected] 1 INSPIRATION AND UNIQUENESS The Bible continues to be the best selling book in the World. But between 1997 and 2007, some speculate that Harry Potter might have surpassed the Bible in sales if it were not for the Gideons. This speaks to the world in which we now find ourselves. There is tremendous interest in things that are “spiritual” but much less interest in the true God revealed in the Bible. The Bible never tries to prove that God exists. He is everywhere assumed to be. Read Exodus 3:14 and write what you learn: ____________________________ _________________________________________________________________ The God who calls Himself “I AM” inspired a divinely authorized book. The process by which the book resulted is “God-breathed.” The Spirit moved men who wrote God-breathed words. Read the following verses and record your thoughts: 2 Timothy 3:16-17__________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________ Do a word study on “scripture” from the above passage, and write the results here: ____________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________ -

Canons of the New Testament

Canons of the New Testament Marcion Irenaeus Origen Eusebius Momsen List 140 CE - Rome 180 CE - Lyons 230 CE - Alexandria 325 CE - Rome 360 CE – St. Gall The Gospel Mark Matthew Matthew Matthew Galatians Luke Mark Mark Mark Corinthians Matthew Luke Luke John Romans John John John Luke Thessalonians Acts Acts Acts Romans Laodiceans Romans Romans Romans 1 Corinthians Colossians 1 Corinthians 1 Corinthians 1 Corinthians 2 Corinthians Philippians 2 Corinthians 2 Corinthians 2 Corinthians Galatians Philemon Galatians Galatians Galatians Ephesians Ephesians Ephesians Ephesians Philippians Philippians Philippians Philippians Colossians Colossians Colossians Colossians 1 Thessalonians 1 Thessalonians 1 Thessalonians 1 Thessalonians 2 Thessalonians 2 Thessalonians 2 Thessalonians 2 Thessalonians 1 Timothy 1 Timothy 1 Timothy 1 Timothy 2 Timothy 2 Timothy 2 Timothy 2 Timothy Titus Titus Titus Titus Philemon James (?) Philemon 1 Peter Acts 1 Peter 1 Peter 1 John Revelation of John 1 John 1 John 1 Clement 1 John Revelation of John Revelation of John Disputed Books 2 John Shepherd Hermas Hebrews 3 John Disputed Books James 1 Peter Hebrews 2 Peter 2 Peter 2 John II Peter 3 John II John Jude III John Revelation of John James Rejected Books Jude Gospel of Peter Epistle of Barnabas Acts of Peter Shepherd of Hermas Preaching of Peter Didache Revelation of Peter Gospel according to the Acts of Paul Shepherd of Hermas Hebrews Second Epistle of Clement Epistle of Barnabas Teachings of the Apostles Gospel of Thomas Gospel of Matthias Gospel of the Hebrews -

The Bible’ in Late Antiquity*

PSEUDEPIGRAPHY, AUTHORSHIP, AND THE RECEPTION OF ‘THE BIBLE’ IN LATE ANTIQUITY* Annette Yoshiko Reed “Who has made the simple folk believe that books belong to Enoch, even though no scriptures existed before Moses? On what basis will they say that there is an apocryphal book of Isaiah? . How could Moses have an apocryphal book?” In his 39th Festal Letter (367 ce), Atha- nasius thus voices his incredulity at the very phenomenon of biblical pseudepigraphy. In his view, the production of books in the names of biblical fi gures can only be a specious and pernicious practice, moti- vated by deceptive aims. “Heretics,” he proclaims, “write these books whenever they want and then grant and bestow upon them dates, so that, by publishing them as if they were ancient, they might have a pretext for deceiving the simple folk!”1 Athanasius expresses these complaints about the pseudepigraphi- cal authors of “apocrypha”2 in the same festal letter so famous for * An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Concordia conference on “The Reception and Interpretation of the Bible in Late Antiquity” in October 2006. The fi nal form has benefi ted much from the questions and suggestions that I received during the conference as well as from the other papers and broader discussions. Warmest thanks to Lorenzo DiTommaso and Lucian Turcescu for the opportunity to participate in such a rich and thought-provoking event. This paper also integrates portions of another conference presentation: “Between ‘Biblical’ and ‘Parabiblical’: Pre-canonical Perspectives on Writing, Reading, and Revelation,” presented at the Society of Biblical Literature Annual Meeting, consultation on “Rethinking the Concept and Categories of ‘Bible’ in Antiquity,” November 2006. -

The Apocryphal and Legendary Life of Christ

Full text of "The Apocryphal and legendary life of Christ; being the whole body of the Apocryphal gospels and other extra canonical literature which pretends to tell of the life and words of Jesus Christ, including much matter which has not before appeared in English. In continuous narrative form, with notes, Scriptural references, prolegomena, and indices" View the book: http://archive.org/details/theapocryphaland00doneuoft THE APOCRYPHAL AND LEGENDARY LIFE OF CHRIST "H. & 5." DOLLAR LIBRARY Similar to this Volume THE TRAINING OF THE TWELVE. By Prof. A. B. Bruce, D.D. THE PARABOLIC TEACHING OF CHRIST. By Prof. A. B. Bruce, D.D. THE MIRACULOUS ELEMENT IN THE GOS PELS. By Prof. A. B. Bruce, D.D. THE HUMILIATION OF CHRIST. By Prof. A. B. Bruce, D.D. THE LIFE OF HENRY DRUMMOND. By Principal George Adam Smith. GESTA CHRISTI. By Charles Loring Brace. THE APOCRYPHAL AND LEGENDARY LIFE OF CHRIST. By J. DeQuincy Donehoo. INDIA: ITS LIFE AND THOUGHT. By John P. Jones, D.D. THE PHILOSOPHY OF THE CHRISTIAN RE LIGION. By Principal A. M. Fairbairn. PULPIT PRAYERS. By Alexander Maclaren, D.D. LECTURES ON THE HISTORY OF PREACH ING. By John Ker, D.D. RELIGIONS OF AUTHORITY AND THE RELI GION OF THE SPIRIT. By Auguste Sabatier. THE LIFE OF CHRIST AS REPRESENTED IN ART. By Dean Frederick W. Farrar. THE APOCRYPHAL AND LEGENDARY LIFE OF CHRIST BEING THE WHOLE BODY OF THE APOCRYPHAL GOSPELS AND OTHER EXTRA CANONICAL LITERATURE WHICH PRETENDS TO TELL OF THE LIFE AND WORDS OF JESUS CHRIST, INCLUDING MUCH MATTER WHICH HAS NOT BEFORE APPEARED IN ENGLISH. -

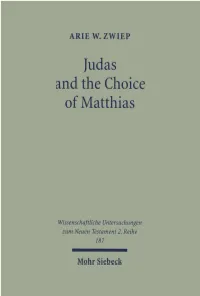

Judas and the Choice of Matthias. a Study on Context and Concern Of

Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament • 2. Reihe Herausgeber/Editor Jörg Frey Mitherausgeber / Associate Editors Friedrich Avemarie • Judith Gundry-Volf Martin Hengel • Otfried Hofius • Hans-Josef Klauck 187 Arie W. Zwiep Judas and the Choice of Matthias A Study on Context and Concern of Acts 1:15-26 Mohr Siebeck ARIE W. ZWIEP, born 1964; Ph.D. University of Durham; currently teaching New Testament at the Evangelische Theologische Hogeschool Ede (formerly Veenendaal) and the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. ISBN 3-16-148452-5 ISSN 0340-9570 (Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 2. Reihe) Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the Internet at http://dnb.ddb.de. © 2004 Mohr Siebeck Tübingen, Germany. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher's written permission. This applies particularly to reproductions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was printed by Druckpartner Rübelmann GmbH in Hemsbach on non-aging paper and bound by Buchbinderei Schaumann in Darmstadt. Printed in Germany. In Honour of My Doktorvater, James D. G. Dunn, Emeritus Professor of Divinity, University of Durham, On the Occasion of His 65 th Birthday Preface In this book I seek to determine the place of Judas Iscariot and his death in the Lukan writings, especially in the episode of the choice of his successor, Acts 1:15-26. It is in a sense to be regarded as a sequel to my Durham doctoral dissertation, The Ascension of the Messiah in Lukan Christology, in which I focused primarily on the first half of the opening chapter of Acts.1 For a number of years I have regarded the section now under investigation, the Judas-Matthias pericope, as one of the most tedious stories in the entire New Testament, an unhappy digression from the more spectacular events of Ascension and Pentecost. -

Apocrypha and Non-Canonical Writings

Apocrypha and non-Canonical Writings Contents Introduction ................................................. 2 Christian Canons .............................................. 2 “Our” Canon ............................................. 2 The Apocrypha ............................................... 3 The View of the Protestant Church .................................... 3 The Old Testament Apocrypha ...................................... 3 Character of the Books ........................................ 3 Historical Apocrypha ......................................... 3 The Legendary Apocrypha ..................................... 3 Apocalyptic Apocrypha ....................................... 3 Didactic Apocrypha ......................................... 4 Reasons for Rejecting the Old Testament Apocrypha ....................... 4 The New Testament Apocrypha ...................................... 5 Categories of the New Testament Apocrypha ........................... 5 Listing of New Testament Apocryphal books ........................... 5 The Pseudepigraphical Writings ...................................... 5 The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha ................................... 6 Apocalyptic Books .......................................... 6 Legendary Books ........................................... 6 Poetical Books ............................................ 6 Didactic (Teaching) Books ...................................... 6 The New Testament Pseudepigrapha ................................... 6 The pseudo-Gospels ........................................ -

The Authority of Scripture: How We Got the New Testament Mako A

The Authority of Scripture: How We Got the New Testament Mako A. Nagasawa, March 18, 2017 Contents Intro: Why Be Concerned? Part One: Criteria for Canonicity Part Two: The Canonical Gospels Part Three: The Gospel of Thomas Part Four: The Gospel of Judas Part Five: The Writing and Canonization of the New Testament Part Six: Discussing the New Testament Canon INTRODUCTION: WHY BE CONCERNED? Q: The DaVinci Code? The story where Jesus has a son by Mary Magdalene? Does Jesus have a skeleton or two in his closet? A: ??? Q: What about the Gospel of Thomas, which Elaine Pagels writes about? Or the Gospel of Judas, which is being ‘rediscovered’? A: ??? Q: Wasn’t the canon a conspiracy of the church hierarchy? A power move? A: ??? PART ONE: CRITERIA FOR CANONICITY 1. Authorship a. Who is supposed to have written this? And when? b. What evidence do we have for authorship? 2. Historical Use a. Did the Christian community broadly come to use this? b. Do we have physical manuscript evidence for it? c. Note: This is important because canonization was not a tops-down imposition achieved by power. Instead, it affirmed a bottoms-up recognition by the broader community, e.g. like a ‘Hall of Fame.’ 3. Content: a. Claim to fulfill the Old Testament story b. Jewish background, language, and ideas Jewish Cultural Assumptions Greco-Roman Cultural Assumptions Our physical bodies are good Physical bodies house the immortal soul, which wants to escape the body Expected ‘resurrection’ – the renewal of the Expected ‘disembodiment’ – the separation of physical world, including our bodies; God’s soul from body true humanity will be raised from the dead Caring for the poor is important Caring for the poor is not important since the body is not important Sexual ethics are important and are derived Have sex with anyone since the body is not from the Genesis creation story important (e.g.