Hidden Gospels. How the Search for Jesus Lost Its

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adult Sunday School Lesson Nassau Bay Baptist Church December 6, 2020

Adult Sunday School Lesson Nassau Bay Baptist Church December 6, 2020 In this beginning of the Gospel According to Luke, we learn why Luke wrote this account and to whom it was written. Then we learn about the birth of John the Baptist and the experience of his parents, Zacharias and Elizabeth. Read Luke 1:1-4 Luke tells us that many have tried to write a narrative of Jesus’ redemptive life, called a gospel. Attached to these notes is a list of gospels written.1 The dates of these gospels span from ancient to modern, and this list only includes those about which we know or which have survived the millennia. Canon The Canon of Scripture is the list of books that have been received as the text that was inspired by the Holy Spirit and given to the church by God. The New Testament canon was not “closed” officially until about A.D. 400, but the churches already long had focused on books that are now included in our New Testament. Time has proven the value of the Canon. Only four gospels made it into the New Testament Canon, but as Luke tells us, many others were written. Twenty-seven books total were “canonized” and became “canonical” in the New Testament. In the Old Testament, thirty-nine books are included as canonical. Canonical Standards Generally, three standards were held up for inclusion in the Canon. • Apostolicity—Written by an Apostle or very close associate to an Apostle. Luke was a close associate of Paul. • Orthodoxy—Does not contradict previously revealed Scripture, such as the Old Testament. -

Mary Magdalene: Her Image and Relationship to Jesus

Mary Magdalene: Her Image and Relationship to Jesus by Linda Elaine Vogt Turner B.G.S., Simon Fraser University, 2001 PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Liberal Studies Program Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Linda Elaine Vogt Turner 2011 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2011 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for "Fair Dealing." Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. APPROVAL Name: Linda Elaine Vogt Turner Degree: Master of Arts (Liberal Studies) Title of Project: Mary Magdalene: Her Image and Relationship to Jesus Examining Committee: Chair: Dr. June Sturrock, Professor Emeritus, English ______________________________________ Dr. Michael Kenny Senior Supervisor Professor of Anthropology ______________________________________ Dr. Eleanor Stebner Supervisor Associate Professor of Humanities, Graduate Chair, Graduate Liberal Studies ______________________________________ Rev. Dr. Donald Grayston External Examiner Director, Institute for the Humanities, Retired Date Defended/Approved: December 14, 2011 _______________________ ii Declaration of Partial Copyright Licence The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. -

326 Crucifixion.Indd 38 19/03/2015 18:03 the Strange World of Crucifixion Science Photo: © 2005 Frederick Zugibe

THE STRANGE WORLD OF CRUCIFIXION SCIENCE Can the medical facts concerning Jesus’s fi nal moments ever be established? MAX HARTSHORN considers the strange world of crucifi xion research, in which bodies both living and dead have been nailed to the cross in the name of science... ost amputated limbs wind up in FACING PAGE: dr frederick zugibe examining one of the hospital incinerator, but Dr his crucifi ed volunteers. Pierre Barbet had other ideas. Having recently lopped off the After six minutes of hanging, the students’ arm of a “vigorous man,” the blood pressure dropped, breathing became MParisian surgeon squared a large nail in the diffi cult, and their skin turned sickly damp. center of its palm and mounted it as one According to Mödder: “What will set in after might the prized head of a slain beast. 1 the end of the sixth minute can be foreseen Barbet then tied a 100lb (45kg) weight by the physician: unconsciousness, intense to the elbow, causing the palm’s fl esh to pallor, sweating. In short: collapse due to buckle and tear under its pull. After about insuffi cient blood supply to the heart and 10 minutes, the initial wound had stretched brain.” 4 into a gaping hole, and Barbet felt it was Evidence shows that the Nazis carried time to give the whole thing a good shake. out the same type of pseudo-crucifi xion as What was left of the cadaverous palm a deadly form of torture. While imprisoned burst open and fell to the fl oor, raising the at Dachau, Father G Delorey was forced to question: was Jesus Christ really crucifi ed watch as his doomed -

SI SO 13 Pages.Indd

Bears as Bigfoot | Truth | Sirius Matter | Leonardo Mysteries | Balles Prize | Creation Astronomy | Dr. Oz the Magazine for Science and Reason Vol. 37 No. 4 | September/October 2013 The Myth of the Mad Genius SYLVIA BROWNE’S PSYCHIC FAILURES: Why Does Anyone Believe Her? Has Global Warming Stopped? Stardust, Smoke and Mirrors News and ESP Belief Lost Lessons of the Strangling Angel Electrocuting Parasites Published by the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry C I –T Ronald A. Lindsay, President and CEO Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Bar ry Karr, Ex ec u tive Di rect or Benjamin Radford, Research Fellow Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow www.csicop.org James E. Al cock*, psy chol o gist, York Univ., Tor on to Thom as Gi lov ich, psy chol o gist, Cor nell Univ. Jay M. Pasachoff, Field Memorial Professor of Mar cia An gell, MD, former ed i tor-in-chief, David H. Gorski, cancer surgeon and re searcher at Astronomy and director of the Hopkins New Eng land Jour nal of Med i cine Barbara Ann Kar manos Cancer Institute and chief Observatory, Williams College Kimball Atwood IV, MD, physician; author; of breast surgery section, Wayne State Univer- John Pau los, math e ma ti cian, Tem ple Univ. Newton, MA sity School of Medicine. Clifford A. Pickover, scientist, au thor, editor, Steph en Bar rett, MD, psy chi a trist; au thor; con sum er Wendy M. Grossman, writer; founder and first editor, IBM T.J. Watson Re search Center. ad vo cate, Al len town, PA The Skeptic magazine (UK) Massimo Pigliucci, professor of philosophy, Willem Betz, MD, professor of medicine, Univ. -

The Apostle Andrew Including Apelles, Aristobulus, Philologus and Stachys, of the Seventy

The Apostle Andrew Including Apelles, Aristobulus, Philologus and Stachys, of the Seventy November 30, 2016 The Calling of Andrew Andrew was born in Bethsaida, along with his brother Simon (Peter) and the Apostle Philip, of the Twelve (John 1:44). Andrew and Simon’s father, Jonah (Matthew 16:17), is never mentioned during the Gospel narratives. By contrast, James and John worked the fishing business with their father, Zebedee (Matthew 4:21). Some early accounts stated1 that Andrew and Simon were orphans, and that the fishing business, along with having bought their own boat (Luke 5:3), was a necessity for their support. Poverty and hard work were something that they had grown up with from childhood. Andrew had been a follower of John the Baptist, along with others of the Twelve and the Seventy. When John the Baptist pointed out Jesus, saying, “Behold the Lamb of God” (John 1:29, 36), immediately Andrew began to follow Jesus (John 1:37), but as a disciple, not as an Apostle. After this first calling, which occurred in early 27 AD, Andrew along with the others (Peter, James and John) were still part-time fishermen, but hadn’t been called to be Apostles yet. In late 27 AD, Jesus called them as Apostles, and they left everything to travel with Him full time (Matthew 4:20, 22). Shortly after that, they were sent to heal the sick, raise the dead, cleanse lepers and cast out demons by themselves (Matthew 10:1-8). A miracle was associated with this second calling (Luke 5:1-11). -

Syllabus and Text

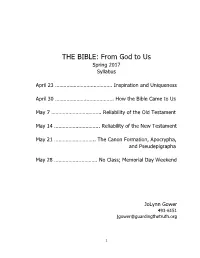

THE BIBLE: From God to Us Spring 2017 Syllabus April 23 …………………………………. Inspiration and Uniqueness April 30 ………………….………………. How the Bible Came to Us May 7 …………………………….. Reliability of the Old Testament May 14 ………………………….. Reliability of the New Testament May 21 ……………………….. The Canon Formation, Apocrypha, and Pseudepigrapha May 28 ………………..………. No Class; Memorial Day Weekend JoLynn Gower 493-6151 [email protected] 1 INSPIRATION AND UNIQUENESS The Bible continues to be the best selling book in the World. But between 1997 and 2007, some speculate that Harry Potter might have surpassed the Bible in sales if it were not for the Gideons. This speaks to the world in which we now find ourselves. There is tremendous interest in things that are “spiritual” but much less interest in the true God revealed in the Bible. The Bible never tries to prove that God exists. He is everywhere assumed to be. Read Exodus 3:14 and write what you learn: ____________________________ _________________________________________________________________ The God who calls Himself “I AM” inspired a divinely authorized book. The process by which the book resulted is “God-breathed.” The Spirit moved men who wrote God-breathed words. Read the following verses and record your thoughts: 2 Timothy 3:16-17__________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________ Do a word study on “scripture” from the above passage, and write the results here: ____________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________ -

BSTS Newsletter No. 39

RECENT PUBLICATIONS Sindon, the official journal of the Centro Internazionale di Sindonologia, nos. 5-6, December 1993; no. 7, June 1994 Review by the Editor These two latest issues have recently been received. No 5-6 includes the following articles: [i] by architect Andrea Bruno about the planning that went into the crystal display case that now protects the Shroud in the Choir of Turin Cathedral; [ii] by Gino Moretto, Secretary of Turin's Centro Internazionale di Sindonologia about the move of the Shroud to its new home; [iii] by Jesuit Michele Casassa about the final stage of the Shroud's journey from Chambery to Twin in 1578; [iv] by Sardinian surgeon Tarquinio Ladu comparing the crucifixion of two missionary priests in Japan in 1597 with what is known of Roman procedure; and [v] by Mario Moroni arguing from experiments that the low inner temperature of the casket in which the Shroud was kept at the time of the 1532 fire, and various types of irradiation considered, cannot have had any effect on the date of the Shroud arrived at by carbon dating. This issue includes fine photos of the new Shroud display case in Turin Cathedral. Issue 7 includes articles: [i] by Monsignor Adolfo Barberis (1884-1967) on the history of devotion to the Holy Face; [ii] by Giuseppe Ghiberti on the claims made in the recent Jesus Conspiracy book by Holger Kersten and Elmar Gruber; [iii] by Milan professor of Forensic Medicine Pierluigi Baima Bollone insisting that the man of the Shroud was definitely dead when his image was imprinted on the cloth; and [iv] memorials to Giuseppe Pia, Father Peter Rinaldi, and other deceased "greats" of this century associated with the Turin Shroud. -

Copyrighted Material

25555 Text 10/7/04 8:56 AM Page 13 1 the enigma of the holy shroud The Shroud of Turin is the holiest object in Christendom. To those who believe, it is proof not only of Jesus the man, but it is also evidence of the Resurrection, the central dogma for hundreds of millions of the faithful. Regarded as the winding sheet, the burial cloth of Jesus, it is revered by many, and on the rare instances when it is displayed, the lines to view the Shroud go on for hours. The Shroud measures fourteen feet three inches long and three feet seven inches wide. It depicts the full image of a six-foot-tall man with the visible consequences of a savage beating and cruel death on the cross, in other words, crucifixion. Belief in the authenticity of the Shroud is not uni- versal. To critics it is a medieval production, created either by paint or by a more remarkable process not to be duplicated until photography was in- vented in the nineteenth century. Nevertheless, a fake. Despite the debate about the Shroud’s authenticity, it has been de- scribed as “one of the most perplexing enigmas of modern time.” This enigma has been the subject of study by an army of chemists, physicists, pathologists, biblical scholars, and art historians. Experts on textiles, pho- tography, medicine, and forensic science have all weighed in with an opin- ion.1 Had theCOPYRIGHTED image on the burial cloth MATERIALbeen that of Charlemagne or Napoleon, the debate might have proceeded along scientific lines. -

Canons of the New Testament

Canons of the New Testament Marcion Irenaeus Origen Eusebius Momsen List 140 CE - Rome 180 CE - Lyons 230 CE - Alexandria 325 CE - Rome 360 CE – St. Gall The Gospel Mark Matthew Matthew Matthew Galatians Luke Mark Mark Mark Corinthians Matthew Luke Luke John Romans John John John Luke Thessalonians Acts Acts Acts Romans Laodiceans Romans Romans Romans 1 Corinthians Colossians 1 Corinthians 1 Corinthians 1 Corinthians 2 Corinthians Philippians 2 Corinthians 2 Corinthians 2 Corinthians Galatians Philemon Galatians Galatians Galatians Ephesians Ephesians Ephesians Ephesians Philippians Philippians Philippians Philippians Colossians Colossians Colossians Colossians 1 Thessalonians 1 Thessalonians 1 Thessalonians 1 Thessalonians 2 Thessalonians 2 Thessalonians 2 Thessalonians 2 Thessalonians 1 Timothy 1 Timothy 1 Timothy 1 Timothy 2 Timothy 2 Timothy 2 Timothy 2 Timothy Titus Titus Titus Titus Philemon James (?) Philemon 1 Peter Acts 1 Peter 1 Peter 1 John Revelation of John 1 John 1 John 1 Clement 1 John Revelation of John Revelation of John Disputed Books 2 John Shepherd Hermas Hebrews 3 John Disputed Books James 1 Peter Hebrews 2 Peter 2 Peter 2 John II Peter 3 John II John Jude III John Revelation of John James Rejected Books Jude Gospel of Peter Epistle of Barnabas Acts of Peter Shepherd of Hermas Preaching of Peter Didache Revelation of Peter Gospel according to the Acts of Paul Shepherd of Hermas Hebrews Second Epistle of Clement Epistle of Barnabas Teachings of the Apostles Gospel of Thomas Gospel of Matthias Gospel of the Hebrews -

The Bible’ in Late Antiquity*

PSEUDEPIGRAPHY, AUTHORSHIP, AND THE RECEPTION OF ‘THE BIBLE’ IN LATE ANTIQUITY* Annette Yoshiko Reed “Who has made the simple folk believe that books belong to Enoch, even though no scriptures existed before Moses? On what basis will they say that there is an apocryphal book of Isaiah? . How could Moses have an apocryphal book?” In his 39th Festal Letter (367 ce), Atha- nasius thus voices his incredulity at the very phenomenon of biblical pseudepigraphy. In his view, the production of books in the names of biblical fi gures can only be a specious and pernicious practice, moti- vated by deceptive aims. “Heretics,” he proclaims, “write these books whenever they want and then grant and bestow upon them dates, so that, by publishing them as if they were ancient, they might have a pretext for deceiving the simple folk!”1 Athanasius expresses these complaints about the pseudepigraphi- cal authors of “apocrypha”2 in the same festal letter so famous for * An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Concordia conference on “The Reception and Interpretation of the Bible in Late Antiquity” in October 2006. The fi nal form has benefi ted much from the questions and suggestions that I received during the conference as well as from the other papers and broader discussions. Warmest thanks to Lorenzo DiTommaso and Lucian Turcescu for the opportunity to participate in such a rich and thought-provoking event. This paper also integrates portions of another conference presentation: “Between ‘Biblical’ and ‘Parabiblical’: Pre-canonical Perspectives on Writing, Reading, and Revelation,” presented at the Society of Biblical Literature Annual Meeting, consultation on “Rethinking the Concept and Categories of ‘Bible’ in Antiquity,” November 2006. -

Shroud News Issue #87 February 1995

A NEWSLETTER ABOUT RESEARCH ON THE HOLY SHROUD OF TURIN published in Australia for Worldwide circulation edited by REX MORGAN, Author of several books on the Shroud Issue Number 87 FEBRUARY 1995 The Holy Shroud in its silver casket now displayed in Turin Cathedral in this glass case during repairs to the Guarini Chapel built for it in 1578 [Pic: Centro Internazionale di Sindonologia, Turin] 2 SHROUD NEWS No 87 (February 1995) EDITORIAL Our first edition for 1995 contains a major article by the Russian scientists Ivanov and Kouznetsov. It was Kouznetsov who caused worldwide interest with his description of this work given in Rome in 1993. It sets out to show reasons for the C14 testing of 1988 being completely incorrect. The article is an important part of the Shroud research record but is pretty heavy going for the non-scientist. Also in this issue Bro. Michael Buttigieg of Malta rebuffs the South African claim last year that the image is a photograph and historian Professor Dan Scavone's review of the book by Picknett and Prince appears to demolish their claim that it was a painting by da Vinci. It is an interesting sidelight that in the advertising brochure for Turin Shroud - In Whose Image? (Picknett and Prince) the photograph of the negative image has been printed backwards. Also in this issue from the pen of Scavone is an important historical article about the Shroud's French period. I have only recently noted that in his excellent book Sindone O No one of Italy's most eminent sindonologists, Professor Pier Luigi Baima Bollone makes the comment that there are numerous Shroud publications in the world ranging from properly printed magazines to simple home-made bulletins. -

The Grail Hunters Timeline: Tracking Searchers for the Holy Grail by George Smart

The Grail Hunters Timeline: Tracking Searchers for the Holy Grail by George Smart Chapter 6: 2006 into the future A complete guide to modern-day Grail researchers, theories, news, books, movies, TV, and explorations. Includes the Knights Templar, Oak Island, Rennes- le-Château, The Da Vinci Code , the Gospel of Judas, Holy Blood, Holy Grail , the Shugborough Monument, the Newport Tower, Rosslyn Chapel, the Jesus Bloodline theory, and much more: year by year, often month by month, for the last 60 years. Key: Books, Articles, and Papers Documentaries, Movies, and DVD’s Vatican News Key Events Items in yellow are questionable and need additional verification. Want to help? January 2006 Picknett and Prince publish The Sion Revelation: The Truth about the Guardians of Christ ’s Sacred Bloodline. German network ZDF shows Terra X: Geheimakte Sakrileg – Der Mythos von Rennes -le - Ch âteau exposes the fraudulent claim of treasure or secrets at Rennes-le-Château, featuring Jean- Luc Chaumeil, Henry Lincoln, Jan Rüdiger (Humboldt University History Professor), Antoine Captier and Claire Corbu, and journalist Jean-Jacques Bedu. Jean-Luc Chaumeil Antoine Captier Jan Rüdiger Henry Lincoln Jean-Jacques Bedu BBC One shows Richard Hammond and The Holy Grail with host Richard Hammond (born 1969), Tom Asbridge, Reverend Robin Griffith-Jones (Master of the Temple Church, London), Ian Robertson, Geoffrey Ashe (Arthurian scholar), Richard Barber (British historian), Simon Cox, Stephen O’Shea, Karen McDermott, Gerald O’Collins (Professor of Christology at Rome's Pontifical Gregorian University), and an uncredited American psychic musing about Rosslyn Chapel. Richard Stephen O’Shea Geoffrey Ashe Gerald Hammond O’Collins February 2006 Andrew Sinclair publishes Rosslyn .