The Employment Ofnegro Troops

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zones PTZ 2017

Zones PTZ 2017 - Maisons Babeau Seguin Pour construire votre maison au meilleur prix, rendez-vous sur le site de Constructeur Maison Babeau Seguin Attention, le PTZ ne sera plus disponible en zone C dès la fin 2017 et la fin 2018 pour la zone B2 Région Liste Communes N° ZONE PTZ Département Commune Région Département 2017 67 Bas-Rhin Adamswiller Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Albé Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Allenwiller Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Alteckendorf Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Altenheim Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Altwiller Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Andlau Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Artolsheim Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Aschbach Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Asswiller Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Auenheim Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Baerendorf Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Balbronn Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Barembach Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Bassemberg Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Batzendorf Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Beinheim Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Bellefosse Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Belmont Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Berg Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Bergbieten Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Bernardvillé Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Berstett Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Berstheim Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Betschdorf Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Bettwiller Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Biblisheim Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Bietlenheim Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Bindernheim Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Birkenwald Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Bischholtz Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Bissert Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Bitschhoffen Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Blancherupt Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Blienschwiller Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Boesenbiesen Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Bolsenheim Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Boofzheim Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin Bootzheim Alsace C 67 Bas-Rhin -

(M Supplément) Administration Générale Et Économie 1800-1870

Archives départementales du Bas-Rhin Répertoire numérique de la sous-série 15 M (M supplément) Administration générale et économie 1800-1870 Dressé en 1980 par Louis Martin Documentaliste aux Archives du Bas-Rhin Remis en forme en 2016 par Dominique Fassel sous la direction d’Adélaïde Zeyer, conservateur du patrimoine Mise à jour du 19 décembre 2019 Sous-série 15 M – Administration générale et économie, 1800-1870 (M complément) Page 2 sur 204 Sous-série 15 M – Administration générale et économie, 1800-1870 (M complément) XV. ADMINISTRATION GENERALE ET ECONOMIE COMPLEMENT Sommaire Introduction Répertoire de la sous-série 15 M Personnel administratif ........................................................................... 15 M 1-7 Elections ................................................................................................... 15 M 8-21 Police générale et administrative............................................................ 15 M 22-212 Distinctions honorifiques ........................................................................ 15 M 213 Hygiène et santé publique ....................................................................... 15 M 214-300 Divisions administratives et territoriales ............................................... 15 M 301-372 Population ................................................................................................ 15 M 373 Etat civil ................................................................................................... 15 M 374-377 Subsistances ............................................................................................ -

Oil HERRLISHEIM by C CB·;-:12Th Arind

i• _-f't,, f . ._,. ... :,.. ~~ :., C ) The Initial Assault- "Oil HERRLISHEIM by C_CB·;-::12th Arind Div ) i ,, . j.. ,,.,,\, .·~·/ The initial assault on Herrli sheim by CCB, ' / 12th Armored Division. Armored School, student research report. Mar 50. ~ -1 r 2. 1 J96§ This Docuntent IS A HOLDING OF THE ARCHIVES SECTION LIBRARY SERVICES FORT LEAVENWORTH, KANSAS I . DOCUMENT NO. N- 2146 .46 COPY NO. _!_ ' A RESEARCH REPORT Prepared at THE ARMORED SCHOOL Fort Knox Kentucky 1949- 1950 <re '4 =#= f 1 , , R-5 01 - □ 8 - I 'IHE INITIAL ASSAULT ON HERRLISHEIM BY COMBAT COMMAND B, 12th ARMORED DIVISION A RESEARCH REPORT PREPARED BY COI\AMITTEE 7, OFFICERS ADVANCED ~OUR.SE THE ARMORED SCHOOL 1949-1950 LIEUTENANT COLONEL GAYNOR vi. HATHNJAY MAJOR "CLARENCE F. SILLS MAJOR LEROY F, CLARK MAJOR GEORGE A. LUCEY ( MAJ OR HAROLD H. DUNvvOODY MAJ OR FRANK J • V IDLAK CAPTAIN VER.NON FILES CAPTAIN vHLLIAM S. PARKINS CAPTAIN RALPH BROWN FORT KNCOC, KENTlCKY MARCH 1950 FOREtfORD Armored warfare played a decisive role in the conduct of vforld War II. The history of th~ conflict will reveal the outstanding contri bution this neWcomer in the team of ground arms offered to all commartiers. Some of the more spectacular actions of now famous armored units are familiar to all students of military history. Contrary to popular be lief, however, not all armored actions consisted of deep slashing drives many miles into enemy territory. Some armored units were forced to engage in the more unspectacular slugging actions against superior enemy forces. One such action, the attack of Combat Comnand B, 12th Armored Division, against HERRLISHEIM, FRANCE, is reviewed in this paper. -

Zonage CLEEBOURG 1/2000

9 10 31 11DER BRISSETISCHE KOPF 29 34 32 35 36 37 N 38 30 183 281 12 114 39 N 282 33 115 13 116 117 243 118 120 157 119 121 123 124 122 28 40 126244 125 172 N 127 283 158 113 112 264 128 141 129130 131 140 132 173 159 133 245246 27 111 41 134 174 136 160 81 135 139 175 82 83 84 261 137 142 176 164 143 85 161 177 178 138 IN 86 139 179 AM SANDBERG 26 138 180 87 140 42 144 181 141 88 163 145 162 142143 IN DER KUCHENBACH 89 274 90 146 163 92 162 137 149 91 265 43 93 94 25 136 147 164 150 9596 n 171 161 i 165 97 260 135 g 170 74 m 151 r 98 160 e 152 148 166 u 253 99 h o 159 C b 167 101 73 100 102 l m 75 IN IN 158 a 44 e 103 r s 168 104 144 u s 109 r 127 i 157 169 155 t 134 153 106 i W 71 à 76 108 156 154 153 d 259 24 105 152 g 126 154 u 72 262 d 151 e CLIMBACH 45 8 247 w 129 155 2 19 77 f ° 150 125 130 n 18 70 o 156 . 149 h D 17 s 124 128 . 78 263 r R 16 79 148 e 69 l 131 7 15 107 l 46 °7 68 237 e 122 123 133 14 147 K 121 132 n 117 e 67 l 13 66 23 DER KASTANIENWALD 120 ta IM SPITELHOF 80 118 n 165 146 116 e 12 IM SPITELHOF 258 115 65 119 m 11 235 166 114 112 te 266 47 r 234 113 111 a 109 p 10 é 64 167 182 d 242 171 170 22 110 te 9 172 8 21 233 174173 48 u 63 108 o 7 22 175 R 23 104 62 103 24 18 6 107 25 232 176 49 26 257 61 272 5 236 106 27 4 105 177 DER BRISSETISCHE KOPF 192 3 29 231 21 70 2 239 1 50 56 59 69 240 52 68 1 n 241 i 2 230 67 100 102 30 m e 63 66 101 h 3 178 31 C IM WOLF 60 l 65 99 IM WOLF 32 a 229 r 267 180181 92 190 64 u 33 r 5 4 248 182 20 79 98 59 l IM STADENBERG 78 e 6 249 252 s 250 238 61 NTa 34 s 7 91 86 58 e 89 91 a 8 228 -

Tourist Sites and the Routes Routes the and Sites Tourist Major the All Shows Map a , Back the Four-À-Chaux Fortress Four-À-Chaux

Rheinau-Honau (Germany). Rheinau-Honau Rheinau-Freistett (Germany), (Germany), Rheinau-Freistett www.tourisme-alsacedunord.fr Drusenheim, Haguenau, Haguenau, Drusenheim, Betschdorf, Drachenbronn, Drachenbronn, Betschdorf, Relax on one of the many terraces. many the of one on Relax Tel. +33 (0)3 88 80 30 70 30 80 88 (0)3 +33 Tel. pools swimming Covered all year round for your shopping. shopping. your for round year all Niederbronn-les-Bains 77 enjoy the attractive pedestrian areas areas pedestrian attractive the enjoy Tel. +33 (0)3 88 06 59 99 59 06 88 (0)3 +33 Tel. , , Wissembourg and Haguenau Tel. +33 (0)3 88 09 84 93 93 84 09 88 (0)3 +33 Tel. Bischwiller, Reichshoffen. Bischwiller, Haguenau Haguenau Morsbronn-les-Bains Haguenau, Wissembourg, Wissembourg, Haguenau, 76 el. +33(0)3 88 94 74 63 74 94 88 +33(0)3 el. T Shopping pools swimmming air Open loisirs-detente-espaces-loisirs.html www.didiland.fr www.didiland.fr air ballooning Seebach ballooning air www.ckbischwiller.e-monsite.com www.brumath.fr/mairie-brumath/ Tel. +33 (0)3 88 09 46 46 46 46 09 88 (0)3 +33 Tel. Ballons-Club de Seebach / Hot Hot / Seebach de Ballons-Club 62 Tel. +33 (0)6 42 52 27 01 27 52 42 (0)6 +33 Tel. 04 04 02 51 88 Tel. +33 (0)3 +33 Tel. www.au-cheval-blanc.fr Morsbronn-les-Bains Morsbronn-les-Bains www.total-jump.fr Bischwiller Brumath Brumath Tel. +33 (0)3 88 94 41 86 86 41 94 88 (0)3 +33 Tel. -

UF00047649 ( .Pdf )

Digitized with the permission of the FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF MILITARY AFFAIRS FLORIDA NATIONAL GUARD SOURCE DOCUMENT ADVISORY Digital images were created from printed source documents that, in many cases , were photocopies of original materials held elsewhere. The quality of these copies was often poor. Digital images reflect the poor quality of the source documents. Where possible images have been manipulated to make them as readable as possible. In many cases such manipulation was not possible. Where available, the originals photocopied for publication have been digitized and have been added, separately, to this collection. Searchable text generated from the digital images , subsequently, is also poor. The researcher is advised not to rely solely upon text-search in this collection. RIGHTS & RESTRICTIONS Items collected here were originally published by the Florida National Guard, many as part of its SPECIAL ARCHIVES PUBLICATION series. Contact the Florida National Guard for additional information. The Florida National Guard reserves all rights to content originating with the Guard . DIGITIZATION Titles from the SPECIAL ARCHIVES PUBLICATION series were digitized by the University of Florida in recognition of those serving in Florida's National Guard , many of whom have given their lives in defense of the State and the Nation. FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF MILITARY AFFAIRS Special Archives Publication Number 136 SUMMARY HISTORIES: WORLDWARII AIRBORNE AND ARMOURED DMSIONS State Arsenal St. Francis Barracks St. Augustine, Florida STATE OF FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF MILITARY AFFAIRS OFFICE OF THE ADJUTANT GENERAL POST OFFICE BOX 1008 STATE ARSENAL, ST. AUGUSTINE 32085-1008 These Special Archives Publications are produced as a service to Florida communities, historians and any other individuals, historical or geneaological societies and both national and state governmental agencies which find the information contained therein of use or value. -

Our Wisconsin Boys in Épinal Military Cemetery, France

Our Wisconsin Boys in Épinal Military Cemetery, France by the students of History 357: The Second World War 1 The Students of History 357: The Second World War University of Wisconsin, Madison Victor Alicea, Victoria Atkinson, Matthew Becka, Amelia Boehme, Ally Boutelle, Elizabeth Braunreuther, Michael Brennan, Ben Caulfield, Kristen Collins, Rachel Conger, Mitch Dannenberg, Megan Dewane, Tony Dewane, Trent Dietsche, Lindsay Dupre, Kelly Fisher, Amanda Hanson, Megan Hatten, Sarah Hogue, Sarah Jensen, Casey Kalman, Ted Knudson, Chris Kozak, Nicole Lederich, Anna Leuman, Katie Lorge, Abigail Miller, Alexandra Niemann, Corinne Nierzwicki, Matt Persike, Alex Pfeil, Andrew Rahn, Emily Rappleye, Cat Roehre, Melanie Ross, Zachary Schwarz, Savannah Simpson, Charles Schellpeper, John Schermetzler, Hannah Strey, Alex Tucker, Charlie Ward, Shuang Wu, Jennifer Zelenko 2 The students of History 357 with Professor Roberts 3 Foreword This project began with an email from Monsieur Joel Houot, a French citizen from the village of Val d’Ajol to Mary Louise Roberts, professor of History at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. Mr. Houot wrote to Professor Roberts, an historian of the American G.I.s in Normandy, to request information about Robert Kellett, an American G.I. buried in Épinal military cemetary, located near his home. The email, reproduced here in French and English, was as follows: Bonjour madame...Je demeure dans le village du Val d'Ajol dans les Vosges, et non loin de la se trouve le cimetière américain du Quéquement à Dinozé-Épinal ou repose 5255 sodats américains tombés pour notre liberté. J'appartiens à une association qui consiste a parrainer une ou plusieurs tombes de soldat...a nous de les honorer et à fleurir leur dernière demeure...Nous avons les noms et le matricule de ces héros et également leur état d'origine...moi même je parraine le lieutenant KELLETT, Robert matricule 01061440 qui a servi au 315 th infantry régiment de la 79 th infantry division, il a été tué le 20 novembre 1944 sur le sol de France... -

Rapport Concernant Modification N°1 Et 2 Du Plan Local D'urbanisme

Dossier N°E20000076/67 Modification n°1 et 2 du plan local d’urbanisme intercommunal du Hattgau Rapport concernant Modification n°1 et 2 du plan local d’urbanisme intercommunal du Hattgau Décision de désignation du Tribunal Administratif de STRASBOURG du 28 juillet 2020, dossier N° 20000076/67 Arrêté de M. le Président de la Communauté de Communes de L’Outre Forêt du 20 Août 2020 Roger LETZELTER Commissaire Enquêteur 20, rue des Sapins 67580 MERTZWILLER Novembre 2020 Dossier N°E20000076/67 Page 1 sur 74 Table des matières Table des matières .................................................................................................................................. 1 GENERALITES ........................................................................................................................................... 3 1. OBJET DE L’ENQUÊTE .................................................................................................................. 3 1.1 MODIFICATION N°1 ............................................................................................................. 3 1.1.1 A Hatten création de deux sous‐secteurs de zone UBh ............................................................. 3 1.1.2 A Hatten régularisation de la limite Nord de la zone IAU1 ........................................................ 3 1.1.3 A Hatten rectification du nom d’une rue ................................................................................... 4 1.1.4 Dans toutes les communes du PLUi : Modification du règlement des sous‐secteurs -

World War Ii Veteran’S Committee, Washington, Dc Under a Generous Grant from the Dodge Jones Foundation 2

W WORLD WWAR IIII A TEACHING LESSON PLAN AND TOOL DESIGNED TO PRESERVE AND DOCUMENT THE WORLD’S GREATEST CONFLICT PREPARED BY THE WORLD WAR II VETERAN’S COMMITTEE, WASHINGTON, DC UNDER A GENEROUS GRANT FROM THE DODGE JONES FOUNDATION 2 INDEX Preface Organization of the World War II Veterans Committee . Tab 1 Educational Standards . Tab 2 National Council for History Standards State of Virginia Standards of Learning Primary Sources Overview . Tab 3 Background Background to European History . Tab 4 Instructors Overview . Tab 5 Pre – 1939 The War 1939 – 1945 Post War 1945 Chronology of World War II . Tab 6 Lesson Plans (Core Curriculum) Lesson Plan Day One: Prior to 1939 . Tab 7 Lesson Plan Day Two: 1939 – 1940 . Tab 8 Lesson Plan Day Three: 1941 – 1942 . Tab 9 Lesson Plan Day Four: 1943 – 1944 . Tab 10 Lesson Plan Day Five: 1944 – 1945 . Tab 11 Lesson Plan Day Six: 1945 . Tab 11.5 Lesson Plan Day Seven: 1945 – Post War . Tab 12 3 (Supplemental Curriculum/American Participation) Supplemental Plan Day One: American Leadership . Tab 13 Supplemental Plan Day Two: American Battlefields . Tab 14 Supplemental Plan Day Three: Unique Experiences . Tab 15 Appendixes A. Suggested Reading List . Tab 16 B. Suggested Video/DVD Sources . Tab 17 C. Suggested Internet Web Sites . Tab 18 D. Original and Primary Source Documents . Tab 19 for Supplemental Instruction United States British German E. Veterans Organizations . Tab 20 F. Military Museums in the United States . Tab 21 G. Glossary of Terms . Tab 22 H. Glossary of Code Names . Tab 23 I. World War II Veterans Questionnaire . -

Stress Characterization and Temporal Evolution of Borehole Failure at The

1 Stress Characterization and Temporal Evolution of Borehole Failure 2 at the Rittershoffen Geothermal Project 3 4 Jérôme Azzola1, Benoît Valley2, Jean Schmittbuhl1, Albert Genter3 5 1Institut de Physique du Globe de Strasbourg/EOST, University of Strasbourg/CNRS, Strasbourg, France 6 2Center for Hydrogeology and Geothermics, University of Neuchâtel, Neuchâtel, Switzerland 7 3ÉS géothermie, Schiltigheim, France 8 Correspondence to: Jérôme Azzola ([email protected]) 9 Abstract. In the Upper Rhine Graben, several innovative projects based on the Enhanced Geothermal System (EGS) 10 technology exploit local deep fractured geothermal reservoirs. The principle underlying this technology consists of increasing 11 the hydraulic performances of the natural fractures using different stimulation methods in order to circulate the natural brine 12 with commercially flow rates. For this purpose, the knowledge of the in-situ stress state is of central importance to predict the 13 response of the rock mass to the different stimulation programs. Here, we propose a characterization of the in-situ stress state 14 from the analysis of Ultrasonic Borehole Imager (UBI) data acquired at different key moments of the reservoir development 15 using a specific image correlation technique. This unique dataset has been obtained from the open hole sections of the two 16 deep wells (GRT-1 and GRT-2, ~2500 m) at the geothermal site of Rittershoffen, France. We based our analysis on the 17 geometry of breakouts and of drilling induced tension fractures (DITF). A transitional stress regime between strike-slip and 18 normal faulting consistently with the neighbour site of Soultz-sous-Forêts is evidenced. The time lapse dataset enables to 19 analyse both in time and space the evolution of the structures over two years after drilling. -

Mise En Page:3

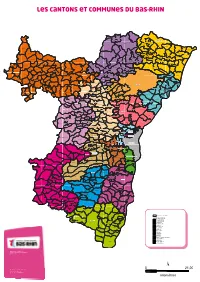

Les cantons et communes du Bas-Rhin WINGENWINGEN NIEDERSTEINBACHNIEDERSTEINBACH SILTZHEIM OBERSTEINBACHOBERSTEINBACH OBERSTEINBACHOBERSTEINBACH WISSEMBOURGWISSEMBOURG ROTTROTT CLIMBACHCLIMBACH CLIMBACHCLIMBACH OBERHOFFEN-LES-WISSEMBOURGOBERHOFFEN-LES-WISSEMBOURG LEMBACHLEMBACHLEMBACH STEINSELTZSTEINSELTZ CLEEBOURGCLEEBOURG DAMBACHDAMBACH SCHLEITHALSCHLEITHAL RIEDSELTZRIEDSELTZ SCHLEITHALSCHLEITHAL HERBITZHEIM SALMBACHSALMBACH SCHEIBENHARDSCHEIBENHARD DRACHENBRONN-BIRLENBACHDRACHENBRONN-BIRLENBACH SCHEIBENHARDSCHEIBENHARD WINDSTEINWINDSTEIN NIEDERLAUTERBACHNIEDERLAUTERBACH LAUTERBOURGLAUTERBOURGLAUTERBOURG INGOLSHEIMINGOLSHEIMINGOLSHEIM SEEBACHSEEBACH KEFFENACHKEFFENACH LOBSANNLOBSANNLOBSANN OERMINGEN LANGENSOULTZBACHLANGENSOULTZBACHLANGENSOULTZBACH LOBSANNLOBSANNLOBSANN SIEGENSIEGEN NEEWILLER-PRES-LAUTERBOURGNEEWILLER-PRES-LAUTERBOURG HUNSPACHHUNSPACH MEMMELSHOFFENMEMMELSHOFFEN DEHLINGEN NIEDERBRONN-LES-BAINSNIEDERBRONN-LES-BAINS GOERSDORFGOERSDORF NIEDERBRONN-LES-BAINSNIEDERBRONN-LES-BAINS LAMPERTSLOCHLAMPERTSLOCHLAMPERTSLOCH OBERLAUTERBACHOBERLAUTERBACH LAMPERTSLOCHLAMPERTSLOCHLAMPERTSLOCH SCHOENENBOURGSCHOENENBOURG OBERLAUTERBACHOBERLAUTERBACH MOTHERNMOTHERN RETSCHWILLERRETSCHWILLER ASCHBACHASCHBACH TRIMBACHTRIMBACH BUTTEN TRIMBACHTRIMBACH WINTZENBACHWINTZENBACH CROETTWILLERCROETTWILLER PREUSCHDORFPREUSCHDORF CROETTWILLERCROETTWILLER KESKASTEL KUTZENHAUSENKUTZENHAUSEN VOELLERDINGEN EBERBACH-SELTZEBERBACH-SELTZ WOERTHWOERTH HOFFENHOFFEN OBERROEDERNOBERROEDERN DIEFFENBACH-LES-WOERTHDIEFFENBACH-LES-WOERTH SOULTZ-SOUS-FORETSSOULTZ-SOUS-FORETS -

Téléchargez La Carte Touristique Du Pays D'alsace Du Nord

> deux fleurs : Bernolsheim, POINT D’INFORMATION OFFICE DE TOURISME 11 Musée historique 17 Musée Krumacker 23 27 31 Fort de Schoenenbourg Les musées Musée du bagage Maison de l’archéologie DU PAYS DE HAGUENAU, DE MOTHERN Betschdorf, Geudertheim, Gries, Exposition thématique sur l’histoire de Histoire de la ville de la préhistoire Plusieurs centaines de malles avec sa maison du néolithique A 30 m sous terre : un ouvrage de FORÊT ET TERRE DE POTIERS Maison de la Wacht Gundershoffen, Herrlisheim, Kilstett, Seltz des Celtes aux Romains jusqu’à 7 Musée de la batellerie aux temps modernes. Visites et de bagages avec des pièces Recherches archéologiques la Ligne Maginot des années 1930, 7 rue du Kabach Kriegsheim, Kuhlendorf, Mertzwiller, l’époque de l’Impératrice Adélaïde. 1 rue des Francs Dans un village de bateliers, audio-guidées. Expositions rares et somptueuses. dans le nord de l’Alsace, de la équipé de tous les éléments d’origine. F-67470 MOTHERN Mothern, Munchhausen, Offwiller, Seltz F-67660 BETSCHDORF un musée aménagé dans une temporaires. Haguenau préhistoire à l’ère industrielle Schoenenbourg Tél. +33 (0)3 88 94 86 67 Reimerswiller, Soultz-sous-forêts, Tél. +33 (0)3 88 05 59 79 Tél. +33 (0)3 88 90 77 50 Haguenau Tél. +33 (0)3 88 93 28 23 et vestiges d’anciens thermes Tél. +33 (0)3 88 80 96 19 [email protected] Wissembourg, Zinswiller péniche consacrée toute entière www.tourisme-seltz.fr [email protected] à leurs vies sur le Rhin. Tél. +33 (0)3 88 90 29 39 www.museedubagage.com romains.