Download Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information As of August 1, 2016 Has Been Used in Preparation of This Directory

Information as of August 1, 2016 has been used in preparation of this directory. PREFACE The Central Intelligence Agency publishes and updates the online directory of Chiefs of State and Cabinet Members of Foreign Governments weekly. The directory is intended to be used primarily as a reference aid and includes as many governments of the world as is considered practical, some of them not officially recognized by the United States. Regimes with which the United States has no diplomatic exchanges are indicated by the initials NDE. Governments are listed in alphabetical order according to the most commonly used version of each country's name. The spelling of the personal names in this directory follows transliteration systems generally agreed upon by US Government agencies, except in the cases in which officials have stated a preference for alternate spellings of their names. NOTE: Although the head of the central bank is listed for each country, in most cases he or she is not a Cabinet member. Ambassadors to the United States and Permanent Representatives to the UN, New York, have also been included. Key To Abbreviations Adm. Admiral Admin. Administrative, Administration Asst. Assistant Brig. Brigadier Capt. Captain Cdr. Commander Cdte. Comandante Chmn. Chairman, Chairwoman Col. Colonel Ctte. Committee Del. Delegate Dep. Deputy Dept. Department Dir. Director Div. Division Dr. Doctor Eng. Engineer Fd. Mar. Field Marshal Fed. Federal Gen. General Govt. Government Intl. International Lt. Lieutenant Maj. Major Mar. Marshal Mbr. Member Min. Minister, Ministry NDE No Diplomatic Exchange Org. Organization Pres. President Prof. Professor RAdm. Rear Admiral Ret. Retired Sec. Secretary VAdm. -

Iran's Nuclear Ambitions From

IDENTITY AND LEGITIMACY: IRAN’S NUCLEAR AMBITIONS FROM NON- TRADITIONAL PERSPECTIVES Pupak Mohebali Doctor of Philosophy University of York Politics June 2017 Abstract This thesis examines the impact of Iranian elites’ conceptions of national identity on decisions affecting Iran's nuclear programme and the P5+1 nuclear negotiations. “Why has the development of an indigenous nuclear fuel cycle been portrayed as a unifying symbol of national identity in Iran, especially since 2002 following the revelation of clandestine nuclear activities”? This is the key research question that explores the Iranian political elites’ perspectives on nuclear policy actions. My main empirical data is elite interviews. Another valuable source of empirical data is a discourse analysis of Iranian leaders’ statements on various aspects of the nuclear programme. The major focus of the thesis is how the discourses of Iranian national identity have been influential in nuclear decision-making among the national elites. In this thesis, I examine Iranian national identity components, including Persian nationalism, Shia Islamic identity, Islamic Revolutionary ideology, and modernity and technological advancement. Traditional rationalist IR approaches, such as realism fail to explain how effective national identity is in the context of foreign policy decision-making. I thus discuss the connection between national identity, prestige and bargaining leverage using a social constructivist approach. According to constructivism, states’ cultures and identities are not established realities, but the outcomes of historical and social processes. The Iranian nuclear programme has a symbolic nature that mingles with socially constructed values. There is the need to look at Iran’s nuclear intentions not necessarily through the lens of a nuclear weapons programme, but rather through the regime’s overall nuclear aspirations. -

Rouhani Meter Second Year Report

ROUHANI AFTER TWO YEARS PERFORMANCE REPORT TABLE OF CONTENT INTRODUCTION 1 FOREIGN POLICY PROMISES 3 The Nuclear File Regional challenges Visa Restrictions ECONOMIC PROMISES 8 Legacy of the previous government Economic sanctions and structural challenges Decrease of inflation Economic growth, improving business environment and increasing employment Privatization Strengthening of national currency Oil and gas production Establishment of social housing Improving wages Critics of the government’s economic record SOCIAL & CULTURAL POLICY PROMISES 15 Universal health coverage Re-launch of the National Orchestra and Tehran’s Symphonic Orchestra Improving of the status of teachers The removal of filters on social media Linguistic rights for minorities in Iran Freedom of expression Promotion of gender rights and elimination of gender inequality DOMESTIC POLITICS Release of political prisoners 21 Reopening the Bureau of Political Parties Elimination of discrimination against ethnic and religious minorities Return of Iranian expatriates to Iran Elimination of gender discrimination Charter of Civil Rights Management Saving Lake Urmia Barriers to fulfilling domestic political promises ROUHANI AFTER TWO YEARS: PERFORMANCE REPORT 1 INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION FOREIGN POLICY PROMISES ECONOMIC PROMISES This report provides Iranians and the international community with a detailed SOCIAL & CULTURALPOLICY PROMISES record of the campaign promises of Iran’s president, Hassan Rouhani, and DOMESTIC POLITICS his administration’s efforts to achieve those promises. It offers an in-depth analysis of the administration’s accomplishments and failures by fact-checking for tangible results. This report is divided into four categories: foreign policy, economic policy, social and cultural policy, and domestic policy, covering the major policy areas in which Rouhani promised to prioritize his work as president. -

General Assembly Distr.: General 14 August 2017

United Nations A/72/322 General Assembly Distr.: General 14 August 2017 Original: English Seventy-second session Item 73 (c) of the provisional agenda* Promotion and protection of human rights: human rights situations and reports of special rapporteurs and representatives Situation of human rights in the Islamic Republic of Iran Note by the Secretary-General** The Secretary-General has the honour to transmit to the General Assembly the report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Islamic Republic of Iran, submitted in accordance with Human Rights Council resolution 34/23. * A/72/150. ** The present report was submitted after the deadline as a result of consultations with the Islamic Republic of Iran. 17-13925 (E) 230817 *1713925* A/72/322 Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Islamic Republic of Iran Summary During its thirty-third session, the Human Rights Council appointed Asma Jahangir as Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Islamic Republic of Iran. The present report outlines the activities carried out by the Special Rapporteur since the issuance of her first report to the Council (A/HRC/34/65), examines ongoing issues and presents some of the most recent and pressing developments in the area of human rights in the country. Contents Page I. Introduction ................................................................... 3 II. Charter on Citizens’ Rights ....................................................... 4 III. Civil and political rights ......................................................... 4 A. Right to take part in the conduct of public affairs ................................ 4 B. Rights to freedom of expression, opinion, information and the press ................. 6 C. -

La Elección De Hassan Rouhani En 2013 Y El Desarrollo De La Política Interna

El Colegio de México Centro de Estudios de Asia y África FACCIONALISMO POLÍTICO EN IRÁN: LA ELECCIÓN DE HASSAN ROUHANI EN 2013 Y EL DESARROLLO DE LA POLÍTICA INTERNA Tesis presentada por DOLORES PATRICIA MARÍN DÍAZ para optar al grado de MAESTRÍA EN ESTUDIOS DE ASIA Y ÁFRICA ESPECIALIDAD: MEDIO ORIENTE DIRECTOR: DR. LUIS MESA DELMONTE Ciudad de México, 2017 Agradecimientos En primer lugar, quisiera agradecer a mi familia, a mis padres Catalina y Patricio, que me han apoyado en cada una de las decisiones que he tomado en la vida, sin que el hecho de estudiar una maestría en la Ciudad de México fuera una excepción. Gracias por su apoyo incondicional y por las incontables muestras de cariño a lo largo de este proceso y de todos los que tuvieron que ocurrir antes para poder llegar hasta aquí. Gracias también a Guille y Diana, que son elementos primordiales de esta familia y que me han apoyado en todo momento. Al profesor Luis Mesa, no sólo por haber dirigido este trabajo de investigación, sino por el interés y esfuerzo que puso como asesor y como maestro y por la pasión contagiosa con la que impregna cada una de sus clases. A él, toda mi admiración y cariño. A los profesores del CEAA, que contribuyeron a mi formación compartiendo sus conocimientos, especialmente al profesor Khalid Chami, quien nos mostró la diversidad de facetas del (los) mundo(s) árabe(s) a las que uno puede tener acceso a través de la lengua; y cuyas enseñanzas trascienden el salón de clases. A mis lectores, la profesora Marcela Álvarez y el profesor Moisés Garduño, por haberse tomado el tiempo para leer y comentar la investigación, y por haber compartido sus conocimientos a lo largo de este camino. -

13683 Wednesday JUNE 10, 2020 Khordad 21, 1399 Shawwal 18, 1441 Lavrov Calls U.S

WWW.TEHRANTIMES.COM I N T E R N A T I O N A L D A I L Y 12 Pages Price 50,000 Rials 1.00 EURO 4.00 AED 42nd year No.13683 Wednesday JUNE 10, 2020 Khordad 21, 1399 Shawwal 18, 1441 Lavrov calls U.S. attempts Why COVID-19 claims fewer Payam Niazmand a Bonhams to offer to impose arms embargo lives in Iran compared to dream can come true works by Iranian on Iran ‘ridiculous’ 2 many other countries? 9 for Persepolis 11 artists 12 CIA spy faces death for gathering intel on Qassem Soleimani: Iran TEHRAN — Iranian Judiciary spokesman provided them with intelligence on se- Iranian Gholamhossein Esmaeili announces a CIA curity issues such as the Guards Quds spy who was gathering intelligence about Force and the location of martyr Qassem the IRGC Quds Force and martyr General Soleimani in exchange for U.S. dollars was Qassem Soleimani has been sentenced sentenced to death by the Revolution Court, to death. and the verdict has been confirmed by the “Recently, a person named Seyed Supreme Court and will be implemented economy Mahmoud Mousavi-Mojed, who had soon,” Esmaeili announced during a press connections with Mossad and CIA and conference on Tuesday. 3 to get back Memoirs of Koniko Yamamura, mother of martyr Mohammad Babai, ready for publication TEHRAN – Iranian writer Hamid He- er whose son was martyred during the sam, the Islamic Revolution Artist of the 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq war, and this book on track in Year in 2018, plans to publish memoirs of will cover the memories of the mother Koniko Yamamura, the mother of martyr of the martyr. -

13706 Thursday JULY 9, 2020 Tir 19, 1399 Dhi Al Qada 17, 1441 U.S

WWW.TEHRANTIMES.COM I N T E R N A T I O N A L D A I L Y 12 Pages Price 50,000 Rials 1.00 EURO 4.00 AED 42nd year No.13706 Thursday JULY 9, 2020 Tir 19, 1399 Dhi Al Qada 17, 1441 U.S. bases might Aircraft engine repair NOC president asks UWW Artists making children’s be shut down center to be set up at to accelerate Ghasemi’s day at Mahak by in future 3 Payam Airport 4 medal reallocation 11 storytelling 12 Iran-EAEU trade taskforce holds first meeting online Iran, Syria sign military TEHRAN — The first meeting of Iran-Eur- remove the barriers existing in the way asian Economic Union (EAEU) trade task- of bilateral trade through mutual coop- force, which was set up to expand trade eration.” between the two sides after they inked a Having the annual trade of over $800 preferential agreement in October 2019, billion, the EAEU members play some was held online. significant role in the global trade, and and security agreement The meeting was participated by the expansion of trade with these countries is head of Iran’s Trade Promotion Organ- very important for Iran, he added. ization (TPO), and Iranian ambassador Iran-EAEU trade stands at over $2 See page 2 to Russia, as well as some other Iranian billion for the moment, which could be and EAEU officials, IRIB reported. increased to $5 million in the short-term Addressing the meeting, TPO Head and to $10 billion in the long-term period, Hamid Zadboum said, “We are trying to Zadboum noted. -

Zarif Holds Talks with Aoun Some Countries in Regard to Humanitarian Issues

‘Iranian refugees in Total inks major gas Infantino offers German experts restore 21516Australia not in 5 deal in Iran condolences after artworks at Tehran suitable condition’ Pourheydari passing museum WWW.TEHRANTIMES.COM I N T E R N A T I O N A L D A I L Y VelayatiVe ururgesg EuEurope to wowork for pepeace in MMideasti 2 16 Pages Price 10,000 Rials 38th year No.12693 Wednesday NOVEMBER 9, 2016 Aban 19, 1395 Safar 9, 1438 Citizenship Rights Charter awaiting thumbs-up: ZZarifarif holdsholds ttalksalks wwithith AAounoun presidential advisor EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW POLITICS TEHRAN — Iranian The visit came days after Aoun desk By Maryam Qarehgozlou&Ali Kushki Foreign Minister was elected president. The post had Mohammad Javad Zarif who made a remained vacant for 29 months due Iran says it has finished a draft of the long-waited-for high-profile visit to Beirut starting on to rivalry between powerbrokers in Citizenship Rights Charter after it underwent a thorough Monday held talks with the newly-elected Lebanon. revision, now awaiting for an approval by the Majlis (Iran’s Lebanese President Michel Aoun as well Immediately after his arrival in Beirut, parliament), government, or cabinet. as the prime minister, parliament Speaker, Foreign Minister Zarif held talks with “An initial draft of the Citizenship Rights Charter was and Hezbollah chief. President Aoun. 2 drawn up just months after President Rouhani took office and made available to the public in November 2013,” Elham Aminzadeh, the presidential advisor on citizenship rights, told the Tehran Times on Monday. Aminzadeh said it took until now to come up with the first and second versions of the charter after having listened to public and expert opinions of a pool of resources. -

Petroleum: an Engine for Global Development

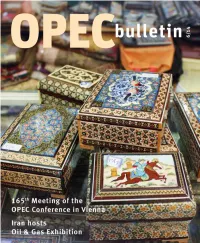

OPEC th International Seminar Petroleum: An Engine for Global Development 3–4 June 2015 Hofburg Palace Vienna, Austria www.opec.org Reasons to be cheerful It was over quite quickly. In fact, the 165th Meeting whilst global oil demand was expected to rise from of the OPEC Conference finished two hours ahead of 90m b/d to 91.1m b/d over the same period. In ad- Commentary schedule. Even the customary press conference, held dition, petroleum stock levels, in terms of days of for- immediately after the Meeting at the Organization’s ward demand cover, remained comfortable. “These Secretariat in Vienna, Austria on June 11 and usually numbers make it clear that the oil market is stable and a busy affair, was most probably completed in record balanced, with adequate supply meeting the steady time. But this brevity of discourse spelled good news growth in demand,” OPEC Conference President, Omar — for OPEC and, in fact, all petroleum industry stake- Ali ElShakmak, Libya’s Acting Oil and Gas Minister, holders. As the much-heralded saying goes — ‘don’t be said in his opening address to the Conference. tempted to tamper with a smooth-running engine’. And Of course, there are still downside risks to the glob- that is exactly what OPEC’s Oil and Energy Ministers al economy, both in the OECD and non-OECD regions, did during their customary mid-year Meeting. They de- and there is continuing concern over some production cided to leave the Organization’s 30 million barrels/ limitations, but with non-OPEC supply growth of 1.4m day oil production ceiling in place and unchanged for b/d forecast over the next year, in general, things are the remainder of 2014. -

Nombramiento Que Expide El Titular Del Ejecutivo Federal a Favor Del C. José Alfonso Zegbe Camarena

DOCUMENTO DE APOYO CON MOTIVO DEL PROCESO DE RATIFICACIÓN DEL H. SENADO DE LA REPÚBLICA, AL NOMBRAMIENTO DEL C. JOSÉ ALFONSO ZEGBE CAMARENA COMO EMBAJADOR EXTRAORDINARIO Y PLENIPOTENCIARIO DE MÉXICO ANTE LA REPÚBLICA ISLÁMICA DE IRÁN Y CONCURRENTE ANTE LA REPÚBLICA ISLÁMICA DE AFGANISTÁN, LA REPÚBLICA KIRGUISA, LA REPÚBLICA ISLÁMICA DE PAKISTÁN, LA REPÚBLICA DE TAYIKISTÁN Y LA REPÚBLICA DE UZBEKISTÁN 2016 Irán (República Islámica del) 23/11/16 Contenido IRÁN (REPÚBLICA ISLÁMICA DEL) A. Datos básicos ............................................................................................................................................... 5 A. 1 Características generales .......................................................................................................................... 5 A.2 Indicadores sociales .................................................................................................................................. 6 A.3 Estructura del Producto Interno Bruto ..................................................................................................... 6 A.4 Coyuntura económica ............................................................................................................................... 7 A.5 Comercio exterior...................................................................................................................................... 7 A.6 Distribución de comercio por países ........................................................................................................ -

The Path Dependent Nature of Factionalism in Post- Khomeini Iran

HH Sheikh Nasser al-Mohammad al-Sabah Publication Series The Path Dependent Nature of Factionalism in Post-Khomeini Iran Ariabarzan Mohammadi Number 13: December 2014 About the Author Dr Ariabarzan Mohammadi is a Visiting Research Fellow with teaching duties in the School of Government and International Affairs at Durham University for 2014-15. Disclaimer The views expressed in the HH Sheikh Nasser al-Mohammad al-Sabah Publication Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the School or of Durham University. These wide ranging Research Working Papers are products of the scholarship under the auspices of the al-Sabah Programme and are disseminated in this early form to encourage debate on the important academic and policy issues of our time. Copyright belongs to the Author(s). Bibliographical references to the HH Sheikh Nasser al-Mohammad al-Sabah Publication Series should be as follows: Author(s), Paper Title (Durham, UK: al-Sabah Number, date). 2 | P a g e The Path Dependent Nature of Factionalism in Post- Khomeini Iran Dr Ariabarzan Mohammadi Abstract The main claim of this paper is that the anti-party system in Iran, or what is known as factionalism, is subject to a path dependent process. The political system in post- Khomeini Iran is not based on political parties. The authoritarian regime in Iran has not developed into a ruling party system as in Egypt under Mubarak. Instead, through its different stages of institutionalisation, the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) has gradually degenerated from what looked like a single party system during the ascendancy of the Islamic Republic Party (IRP) in the first and second Majlis (the Islamic Consultative Assembly of Iran), to an anti-party, factional system that has continued to the present. -

Tehran, Moscow Set Roadmap for Strategic Economic Co-Op

Iran’s parliamentary Japan’s TonenGeneral Iran’s 2016 Olympic Iranian theater 21112group to visit 4 buys first oil uniforms revealed troupe pays tribute NATION Damascus ECONOMY from Iran: sources SPORTS ART& CULTURE to Anton Chekhov WWW.TEHRANTIMES.COM I N T E R N A T I O N A L D A I L Y ‘Iran resolved to open new chapter in cooperation with ASEAN’ 2 12 Pages Price 10,000 Rials 38th year No.12611 Sunday JULY 31, 2016 Mordad 10, 1395 Shawwal 26, 1437 Failed coup Al-Nusra strengthened Turkish Tehran, Moscow set roadmap rebranding unity: ambassador for strategic economic co-op just ‘word EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW By Ali Kushki and Parvin Telli Iran and Russia are to sign a five-year Iranian Communications and Informa- Vaezi and Novak, who co-chaired play’: Iran strategic cooperation plan on more tion Technology Minister Mahmoud the Russian-Iranian intergovernmental TEHRAN — Two weeks after the July 15 coup, the Tehran than 70 industrial projects. Vaezi to Moscow, starting from July 26, commission on trade and economic POLITICAL TEHRAN — Irani- Times sat face-to-face with Turkish ambassador to Tehran The two countries conferred on tak- and his meetings with various Russian cooperation, told reporters about the deskan Foreign Ministry Riza Hakan Tekin to hear his remarks about the pre- and ing bilateral economic partnership into senior officials including Energy Minister outcomes of their meeting in a news spokesman Bahram Qassemi said on post-coup Turkey. a new level during the four-day visit of Alexander Novak. conference on Friday. Thursday that changing the name of Too strong to be defeated by tanks and helicopters, Al-Nusra Front to Jabhat Fatah al-Sh- said the ambassador, hailing the Turkish people’s will.