Contrastive Analysis of American and Arab Nonverbal and Paralinguistic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Protrepticus of Clement of Alexandria: a Commentary

Miguel Herrero de Jáuregui THE PROTREPTICUS OF CLEMENT OF ALEXANDRIA: A COMMENTARY to; ga;r yeu'do" ouj yilh'/ th'/ paraqevsei tajlhqou'" diaskedavnnutai, th'/ de; crhvsei th'" ajlhqeiva" ejkbiazovmenon fugadeuvetai. La falsedad no se dispersa por la simple comparación con la verdad, sino que la práctica de la verdad la fuerza a huir. Protréptico 8.77.3 PREFACIO Una tesis doctoral debe tratar de contribuir al avance del conocimiento humano en su disciplina, y la pretensión de que este comentario al Protréptico tenga la máxima utilidad posible me obliga a escribirla en inglés porque es la única lengua que hoy casi todos los interesados pueden leer. Pero no deja de ser extraño que en la casa de Nebrija se deje de lado la lengua castellana. La deuda que contraigo ahora con el español sólo se paliará si en el futuro puedo, en compensación, “dar a los hombres de mi lengua obras en que mejor puedan emplear su ocio”. Empiezo ahora a saldarla, empleándola para estos agradecimientos, breves en extensión pero no en sinceridad. Mi gratitud va, en primer lugar, al Cardenal Don Gil Álvarez de Albornoz, fundador del Real Colegio de España, a cuya generosidad y previsión debo dos años provechosos y felices en Bolonia. Al Rector, José Guillermo García-Valdecasas, que administra la herencia de Albornoz con ejemplar dedicación, eficacia y amor a la casa. A todas las personas que trabajan en el Colegio y hacen que cumpla con creces los objetivos para los que se fundó. Y a mis compañeros bolonios durante estos dos años. Ha sido un honor muy grato disfrutar con todos ellos de la herencia albornociana. -

Dzhokhar Tsarnaev Had Murdered Krystle Marie Campbell, Lingzi Lu, Martin Richard, and Officer Sean Collier, He Was Here in This Courthouse

United States Court of Appeals For the First Circuit No. 16-6001 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Appellee, v. DZHOKHAR A. TSARNAEV, Defendant, Appellant. APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS [Hon. George A. O'Toole, Jr., U.S. District Judge] Before Torruella, Thompson, and Kayatta, Circuit Judges. Daniel Habib, with whom Deirdre D. von Dornum, David Patton, Mia Eisner-Grynberg, Anthony O'Rourke, Federal Defenders of New York, Inc., Clifford Gardner, Law Offices of Cliff Gardner, Gail K. Johnson, and Johnson & Klein, PLLC were on brief, for appellant. John Remington Graham on brief for James Feltzer, Ph.D., Mary Maxwell, Ph.D., LL.B., and Cesar Baruja, M.D., amici curiae. George H. Kendall, Squire Patton Boggs (US) LLP, Timothy P. O'Toole, and Miller & Chevalier on brief for Eight Distinguished Local Citizens, amici curiae. David A. Ruhnke, Ruhnke & Barrett, Megan Wall-Wolff, Wall- Wolff LLC, Michael J. Iacopino, Brennan Lenehan Iacopino & Hickey, Benjamin Silverman, and Law Office of Benjamin Silverman PLLC on brief for National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, amicus curiae. William A. Glaser, Attorney, Appellate Section, Criminal Division, U.S. Department of Justice, with whom Andrew E. Lelling, United States Attorney, Nadine Pellegrini, Assistant United States Attorney, John C. Demers, Assistant Attorney General, National Security Division, John F. Palmer, Attorney, National Security Division, Brian A. Benczkowski, Assistant Attorney General, and Matthew S. Miner, Deputy Assistant Attorney General, were on brief, for appellee. July 31, 2020 THOMPSON, Circuit Judge. OVERVIEW Together with his older brother Tamerlan, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev detonated two homemade bombs at the 2013 Boston Marathon, thus committing one of the worst domestic terrorist attacks since the 9/11 atrocities.1 Radical jihadists bent on killing Americans, the duo caused battlefield-like carnage. -

This List of Gestures Represents Broad Categories of Emotion: Openness

This list of gestures represents broad categories of emotion: openness, defensiveness, expectancy, suspicion, readiness, cooperation, frustration, confidence, nervousness, boredom, and acceptance. By visualizing the movement of these gestures, you can raise your awareness of the many emotions the body expresses without words. Openness Aggressiveness Smiling Hand on hips Open hands Sitting on edge of chair Unbuttoning coats Moving in closer Defensiveness Cooperation Arms crossed on chest Sitting on edge of chair Locked ankles & clenched fists Hand on the face gestures Chair back as a shield Unbuttoned coat Crossing legs Head titled Expectancy Frustration Hand rubbing Short breaths Crossed fingers “Tsk!” Tightly clenched hands Evaluation Wringing hands Hand to cheek gestures Fist like gestures Head tilted Pointing index finger Stroking chins Palm to back of neck Gestures with glasses Kicking at ground or an imaginary object Pacing Confidence Suspicion & Secretiveness Steepling Sideways glance Hands joined at back Feet or body pointing towards the door Feet on desk Rubbing nose Elevating oneself Rubbing the eye “Cluck” sound Leaning back with hands supporting head Nervousness Clearing throat Boredom “Whew” sound Drumming on table Whistling Head in hand Fidget in chair Blank stare Tugging at ear Hands over mouth while speaking Acceptance Tugging at pants while sitting Hand to chest Jingling money in pocket Touching Moving in closer Dangerous Body Language Abroad by Matthew Link Posted Jul 26th 2010 01:00 PMUpdated Aug 10th 2010 01:17 PM at http://news.travel.aol.com/2010/07/26/dangerous-body-language-abroad/?ncid=AOLCOMMtravsharartl0001&sms_ss=digg You are in a foreign country, and don't speak the language. -

University of Groningen a Cultural History of Gesture Bremmer, JN

University of Groningen A Cultural History Of Gesture Bremmer, J.N.; Roodenburg, H. IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 1991 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Bremmer, J. N., & Roodenburg, H. (1991). A Cultural History Of Gesture. s.n. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 02-10-2021 The 'hand of friendship': shaking hands and other gestures in the Dutch Republic HERMAN ROODENBURG 'I think I can see the precise and distinguishing marks of national characters more in those nonsensical minutiae than in the most important matters of state'. -

IN the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the WESTERN DISTRICT of PENNSYLVANIA DAVID HACKBART, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) V. ) 2:07Cv1

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA DAVID HACKBART, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) 2:07cv157 ) Electronic Filing THE CITY OF PITTSBURGH, and SGT. ) BRIAN ELLEDGE, ) ) Defendant. ) MEMORANDUM OPINION March 23, 2009 I. INTRODUCTION Plaintiff, David Hackbart (“Hackbart”), filed the instant action pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 1983, alleging violation of his rights under the First, Fourth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution of the United States by Defendants, the City of Pittsburgh (the “City”) and Sergeant Brian Elledge (“Elledge”). The parties have filed cross-motions for summary judgment, and the matter is now before the Court. II. STATEMENT OF THE CASE On April 10, 2006, Hackbart was traveling along Murray Avenue in the Squirrel Hill section of the City of Pittsburgh, looking for a place to park his vehicle when he saw an open metered parking space. Plaintiff’s Concise Statement of Undisputed Fact (hereinafter “Pl. CSUF”) ¶¶ 2 - 4; Defendants’ Concise Statement of Material Facts (hereinafter “Def. CSMF”) ¶ 1. As Hackbart was attempting to back into the parking space, a vehicle pulled up behind him and effectively blocked Hackbart’s entry into the parking space. Pl. CSUF ¶ 5; Def. CSMF ¶ 2. The driver of the vehicle behind Hackbart would not back up. Def. CSMF ¶ 6. Frustrated, Hackbart extended his left arm out the window of his vehicle and extended his middle finger to the driver. Pl. CSUF ¶ 6. At that time, Elledge was in uniform traveling along Murray Avenue in the direction opposite of Hackbart, and was driving a marked City of Pittsburgh police vehicle. Pl. -

Unveiling Baubo: the Making of an Ancient Myth for the Degree Field Of

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY Unveiling Baubo: The Making of an Ancient Myth A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Field of Comparative Literary Studies By Frederika Tevebring EVANSTON, ILLINOIS December 2017 2 © Copyright by Frederika Tevebring 2017 All Rights Reserved 3 Abstract “Unveiling Baubo” describes how the mythical figure Baubo was constructed in nineteenth-century German. Associated with the act of exposing herself to the goddess Demeter, Baubo came to epitomize questions about concealment and unveiling in the budding fields of archaeology, philology, psychoanalysis and literary theory. As I show in my dissertation, Baubo did not exist as a coherent mythical figure in antiquity. Rather, the nineteenth-century notion of Baubo was mediated through a disparate array of ancient and contemporary sources centered on the notion of sexual vulgarity. Baubo emerged as a modern amalgam of ancient parts, a myth of a myth invested with the question of what modernity can and should know about ancient Greece. The dissertation centers on the 1989 excavation of the so-called Baubo statuettes, a group of Hellenistic votive figurines discovered at Priene, in modern-day Turkey. The group adheres to a consistent and unique iconography: the face of the female figures is placed directly onto their torso, giving the impression that the vulva and chin merge. Based on the statuettes’ “grotesque- obscene” appearance, archaeologist concluded that they depicted Baubo, the woman who greeted Demeter at Eleusis when the goddess was searching for her abducted daughter Persephone. According to late antique Church Fathers, Demeter refused the locals’ offerings of food and drink until Baubo cheered her up by lifting her skirt, exposing herself to the goddess. -

Many Times We Tend to Use Our Hands to Explain Our Needs and Thoughts

Many times we tend to use our hands to explain our needs and thoughts. The same hand gesture may mean something quite nasty and offensive to a person from a different cultural background. Hand gestures are a very important part of the body language gestures. In this article we shall understand what are hand gestures. What are Hand Gestures? Hand gestures are a way of communicating with others and conveying your feelings. These gestures are most helpful when one is speaking to someone with no language in common. The meanings of hand gestures in different cultures may translate into different things. To explain my point, I take a very common example of former President George W. Bush who had to face a major faux pas during a visit to Australia. He tried to signal a peace sign by waving the two finger or V-sign at the crowd. You may think of this as a simple gesture, but he committed a major error. Instead of his palm facing outwards, it faced inwards. The meaning of this hand gesture in Australia meant he was asking the crowd to go screw themselves! A grave error committed by the then most powerful man in the world. Therefore, it is very important to understand the meanings of gestures before you travel to different countries. Before you communicate with people in different cultures, you need to understand the meaning of gestures. Those considered as a good gestures in one country may be termed as an offensive gesture in some countries. So, if you are a frequent flier to different countries, improve your communication skills by learning the meaning of hand gestures. -

Ascoltare Con Gli Occhi Il Linguaggio Non Verbale E Le Differenze Culturali

Corso di Laurea magistrale in Scienze Del Linguaggio Tesi di Laurea: Ascoltare con gli Occhi Il Linguaggio Non Verbale e le Differenze Culturali Relatore Ch. Prof. Fabio Caon Correlatore Ch. Prof. Graziano Serragiotto Laureando Marco Munari Matricola 820853 Anno Accademico 2014 / 2015 ASCOLTARE CON GLI OCCHI IL LINGUAGGIO NON VERBALE E LE DIFFERENZE CULTURALI INDICE: INTRODUCTION 1. INTERCULTURAL COMMUNICATIVE COMPETENCE 2. NON-VERBAL COMMUNICATION 2.1 KINESICS 2.1.1 FACE AND EMOTIONS 2.1.1.1 HAPPINESS 2.1.1.2 SADNESS 2.1.1.3 FEAR 2.1.1.4 ANGER 2.1.1.5 DISGUST 2.1.1.6 SURPRISE 2.1.1.7 COUNTERFEITING EMOTIONS 2.1.2 THE GAZE 2.1.2.1 GAZE AND MUTUAL GAZE 2.1.2.1.1 REGULATING THE FLOW OF COMMUNICATION 2.1.2.1.2 MONITORING FEEDBACK 2.1.2.1.3 DISPLAYING COGNITIVE ACTIVITY 2.1.2.1.4 EXPRESSING EMOTIONS 2.1.2.1.5 COMMUNICATING THE TYPE OF RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE INTERLOCUTORS 2.1.2.2 DILATION AND CONTRACTION OF PUPILS 2.1.2.3 THE GLANCE AS GUIDE TO THE COGNITIVE PROCESSES 2.1.3 HANDS AND ARMS 2.1.3.1 INDIPENDENT GESTURES 2.1.3.2 DIPENDENT GESTURES 2.1.3.2.1 GESTURES BOUND TO REFERENT/SPEAKER 2.1.3.2.2 GESTURES INDICATIVE OF REFERENT/SPEAKER RELATIONSHIP 2.1.3.2.3 PUNCTUATION GESTURES 2.1.3.2.4 INTERACTIVE GESTURES 2.1.3.3 SELF-HANDLING 2.1.3.4 FREQUENCY OF GESTURES 2.1.3.5 INTERACTIVE SYNCHRONY 2.1.3.6 WIDESPREAD GESTURES 2.1.4 PHYSICAL CONTACT 2.1.5 LEGS AND FEET 2.1.6 DIRECTION OF THE BODY AND POSTURE 2.1.6.1 INTERPERSONAL ATTITUDES 2.1.7 SMELLS AND NOISES OF THE BODY 2.2 PROSSEMICA 2.2.1 LO SPAZIO PERSONALE 2.2.2 INVASIONE DEL TERRITORIO 2.2.3 DENSITÀ ED AFFOLLAMENTO 2.2.4 COMPORTAMENTI SPAZIALI 2.2.4.1 IN ASCENSORE 2.2.4.2 IN MACCHINA 2.2.4.3 DA SEDUTI 2.3 VESTEMICA 2.4 OGGETTEMICA 3 IL LINGUAGGIO PARAVERBALE 3.1 ESPRESSIONE DELLE EMOZIONI 3.2 ATTEGGIAMENTI INTERPERSONALI 3.3 INFORMAZIONI SUL MITTENTE 3.3.1 PERSONALITÀ 3.3.2 CLASSE SOCIALE 3.3.3 SESSO 3.3.4 ETÀ 3.4 PROSODIA E COMPRENSIONE 3.5 PROSODIA E PERSUASIONE 3.6 PROSODIA E TURNI DI PAROLA 3.7 PAUSE E SILENZI 4 NATURAL VS. -

Classical Memories/Modern Identities Paul Allen Miller and Richard H

CLASSICAL MEMORIES/MODERN IDENTITIES Paul Allen Miller and Richard H. Armstrong, Series Editors All Rights Reserved. Copyright © The Ohio State University Press, 2015. Batch 1. All Rights Reserved. Copyright © The Ohio State University Press, 2015. Batch 1. Ancient Sex New Essays EDITED BY RUBY BLONDELL AND KIRK ORMAND THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS • COLUMBUS All Rights Reserved. Copyright © The Ohio State University Press, 2015. Batch 1. Copyright © 2015 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ancient sex : new essays / edited by Ruby Blondell and Kirk Ormand. — 1 Edition. pages cm — (Classical memories/modern identities) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8142-1283-7 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Sex customs—Greece—History. 2. Sex customs—Rome—History. 3. Gender identity in literature. 4. Sex in literature. 5. Homosexuality—Greece—History. I. Blondell, Ruby, 1954– editor. II. Ormand, Kirk, 1962– editor. III. Series: Classical memories/modern identities. HQ13.A53 2015 306.7609495—dc23 2015003866 Cover design by Regina Starace Text design by Juliet Williams Type set in Adobe Garamond Pro Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. Cover image: Bonnassieux, Jean-Marie B., Amor clipping his wings. 1842. Close-up. Marble statue, 145 x 67 x 41 cm. ML135;RF161. Photo: Christian Jean. Musée du Louvre © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY Bryan E. Burns, “Sculpting Antinous” was originally published in Helios 35, no. 2 (Fall 2008). Reprinted with permission. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American Na- tional Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. -

Communications Sent, 1 June to 30 November 2013

A/HRC/31/79 United Nations General Assembly Distr.: General 19 February 2016 English/French/Spanish only Human Rights Council Thirty-first session Agenda items 3, 4, 7, 9 and 10 Promotion and protection of all human rights, civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to development Human rights situations that require the Council’s attention Human rights situation in Palestine and other occupied Arab territories Racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related forms of intolerance, follow-up to and implementation of the Durban Declaration and Programme of Action Technical assistance and capacity-building Communications report of Special Procedures* Communications sent, 1 June to 30 November 2015; Replies received, 1 August 2015 to 31 January 2016 Joint report by the Special Rapporteur on adequate housing as a component of the right to an adequate standard of living, and on the right to non-discrimination in this context; Independent Expert on the enjoyment of human rights by persons with albinism; the Working Group of Experts on people of African descent; the Working Group on arbitrary detention; Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Belarus; the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Cambodia; Independent Expert on the situation of human rights in the Central African Republic; the Special Rapporteur in the field of cultural rights; the Independent expert on the promotion of a democratic and equitable international order; the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human -

Handy Gestures from Around the World and How to Use Them

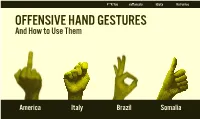

F**K You vaffanculo Idiota Ku Fariiso OFFENSIVE HAND GESTURES And How to Use Them America Italy Brazil Somalia Home Link Link Link F**K You OFFENSIVE HAND Ku Fariiso vaffanculo GESTURES And How to Use Them America Italy Brazil Somalia Idiota Home Link Link Link HANDY GESTURES KU FARIISO F**K YOU And How to Use Them America Italy Brazil Somalia VAFFANCULO IDIOTA Home Link Link Link HANDY GESTURES And How to Use Them America Italy Brazil Somalia KU FARIISO KU F**K YOU VAFFANCULO IDIOTA Home Link Link Link F**K YOU HANDY GESTURES And How to Use Them America Italy Brazil Somalia Home F**K You vaffanculo Idiota Ku Fariiso Handy Gestures From Around The World And How To Use Them America Italy Brazil Greece Home F**K You The Fig Corna Sit on it Handy Gestures From Around The World And How To Use Them America Turkey Brazil Greece Home F**K You The Fig Corna Sit on it The Fig Sign The fig sign is a mildly obscene gesture used in Turkish and Slavic cultures and some other cul- tures that uses two fingers and a thumb. This ges- ture is suposed to represent the female genitalia and most commonly used to deny a request. An- other use of this gesture is for warding off evil eye, jealousy, etc. Home F**K You The Fig Corna Sit on it The Okay Sign In Brazil, the “OK” gesture is Nixon’s visit to Brazil in the ‘50s. roughly equivalent to the fin- While alighting from the aircraft, ger in the US, which means you he lifted both hands to the cam- should not use it when your ho- eras and double-fingered the tel manager asks you how your entire nation. -

Unspoken Diversity: Cultural Differences in Gestures

Qualitative Sociology, Vol. 20, No. 1, 1997 Unspoken Diversity: Cultural Differences in Gestures Dane Archer This paper describes the use of video to explore cultural differences in gestures. Video recordings were used to capture a large sample of international gestures, and these are edited into a documentary video, A World of Gestures: Culture and Nonverbal Communication. This paper describes the approach and methodology used. A number of specific questions are examined: Are there universally understood hand gestures?; Are there universal categories of gestures—i.e., universal messages with unique instances in each society?; Can the exact same gesture have opposite meanings in two cultures?; Can individuals articulate and explain the gestures common in their culture?; How can video methods provide "visual replication" of nuanced behaviors such as gestures?; Are there gender differences in knowing or performing gestures?; and finally, Is global diversity collapsing toward Western gestural forms under the onslaught of cultural imperialism? The research findings suggest that there are both cultural "differences" and also cultural "meta-differences"—more profound differences involving deeply embedded categories of meaning that make cultures unique. KEY WORDS: gestures; culture; cultural differences; nonverbal communication. A BABBLE OF GESTURES Gestures are definitely NOT a universal language, as people who have worked, lived, or studied abroad may have noticed. Travelers sometimes learn this the hard way, committing inadvertent offense by using the cul- turally "wrong" gesture. No sojourner is immune to this hazard, even those traveling with scores of advisers in tow. For example, former President Direct correspondence to Dane Archer, Ph.D., University of California, Santa Cruz, CA 95064.