The Politics of Eradication and the Future of Lgbt Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STRENGTHENING ECONOMIC SECURITY for CHILDREN LIVING in LGBT FAMILIES January 2012

STRENGTHENING ECONOMIC SECURITY FOR CHILDREN LIVING IN LGBT FAMILIES January 2012 Authors In Partnership With A Companion Report to “All Children Matter: How Legal and Social Inequalities Hurt LGBT Families.” Both reports are co-authored by the Movement Advancement Project, the Family Equality Council, and the Center for American Progress. This report was authored by: This report was developed in partnership with: 2 Movement Advancement Project National Association of Social Workers The Movement Advancement Project (MAP) is an independent National Association of Social Workers (NASW) is the largest think tank that provides rigorous research, insight and membership organization of professional social workers in analysis that help speed equality for LGBT people. MAP works the world, with 145,000 members. NASW works to enhance collaboratively with LGBT organizations, advocates and the professional growth and development of its members, to funders, providing information, analysis and resources that create and maintain professional standards, and to advance help coordinate and strengthen their efforts for maximum sound social policies. The primary mission of the social work impact. MAP also conducts policy research to inform the profession is to enhance human well-being and help meet the public and policymakers about the legal and policy needs of basic human needs of all people, with particular attention to LGBT people and their families. For more information, visit the needs and empowerment of people who are vulnerable, www.lgbtmap.org. oppressed, and living in poverty. For more information, visit www.socialworkers.org. Family Equality Council Family Equality Council works to ensure equality for LGBT families by building community, changing public opinion, Acknowledgments advocating for sound policy and advancing social justice for all families. -

Correctional Staff Attitudes Toward Transgender Individuals

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Graduate School of Professional Psychology: Doctoral Papers and Masters Projects Graduate School of Professional Psychology 2020 Correctional Staff Attitudes Toward Transgender Individuals Neilou Heidari Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/capstone_masters Part of the Clinical Psychology Commons, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, and the Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. TRANSPHOBIA AMONG CORRECTIONAL STAFF Correctional Staff Attitudes Toward Transgender Individuals A DOCTORAL PAPER PRESENTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF PROFESSIONAL PSYCHOLOGY OFFICE OF GRADUATE STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF DENVER IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY BY NEILOU HEIDARI, M.A. JULY 13, 2020 APPROVED: Apryl Alexander, Psy.D., Chair e Ko 'Bfieann hrt, Ph.D. ____________________ Bradley McMillan, Ph.D. TRANSPHOBIA AMONG CORRECTIONAL STAFF 2 Abstract Compared to the general population, transgender individuals face higher rates of victimization, violence, substance use, physical health issues, and mental health problems. Transgender people are more likely to face barriers in finding and maintaining employment and housing due to discrimination. As a result, they are more likely to participate in illegal economies such as sex work and drug distribution. These factors contribute to the overrepresentation of transgender people in jails and prisons in the United States. Specifically, 16% of transgender adults have been incarcerated, compared to 2.7% of the general population. While under custody, transgender individuals are at risk of verbal, physical, and sexual abuse and harassment by correctional staff. -

Hate Crime Laws and Sexual Orientation

The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare Volume 26 Issue 3 September Article 2 September 1999 Hate Crime Laws and Sexual Orientation Elizabeth P. Cramer Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/jssw Part of the Gender and Sexuality Commons, Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons, and the Social Work Commons Recommended Citation Cramer, Elizabeth P. (1999) "Hate Crime Laws and Sexual Orientation," The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare: Vol. 26 : Iss. 3 , Article 2. Available at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/jssw/vol26/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you by the Western Michigan University School of Social Work. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hate Crime Laws and Sexual Orientation ELIZABETH P. CRAMER Virginia Commonwealth University School of Social Work This articleprovides definitionsfor hate crimes, a summary of nationaldata on hate crime incidents, and descriptions of federal and state hate crime laws. The authorpresents variousarguments in supportof and againsthate crime laws, and the inclusion of sexual orientationin such laws. The author contends that it is illogical and a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment to exclude sexual orientationfrom hate crime laws. The perpetratorsof hate crime incidents, regardess of the target group, have similar motives and perpetratesimilar types of assaults; the victims experience similarphysical and psychological harm. Excluding a class of persons who are targets of hate crimes denies them equal protection under the law because the Equal ProtectionClause of the FourteenthAmendment establishes a fundamental right to equal benefit of laws protecting personal security. Laramie, Wyoming, October 7, 1998: A gay college student was brutally beaten by two men who smashed his skull with a pistol butt and lashed him to a split-rail fence. -

Rethinking the Binary

Oppressor and Oppressed: Rethinking the Binary Jasbir Puar Discusses Domestic Violence Narika was founded in Berkeley in 1991 to aid South Asian battered women. Jasbir Puar was a board member from 1995 to 1998, as well as a volunteer and consultant on the Youth Outreach Project through June 1999. She spoke to Munia in March 1998 about addressing questions of same-sex domestic violence in South Asian communities through Narika. M: Tell me about Narika’s same-sex initiatives and how you got to that place. J: Several years ago we tried to put together a support group for South Asian women. We had long discussions about language: in the end we said it was for lesbians, bisexuals, questioning f2m transgendered persons and women who love women. We didn’t get any calls during the time the advertisement ran. My goal was to basically have this space that Trikone didn’t seem to be really addressing. My sense of why the group didn’t come together is that the kinds of communities we live in need different kinds of outreach. We started, for example, doing outreach at Bhangra gigs and at straight, queer, and mixed events. HIV/AIDS organizations generally do this kind of outreach, but not queer domestic violence organizations, whereas South Asian domestic violence organizations might focus on tabling at cultural events. So we kind of hybridized the approaches and it was very successful. M: What other kinds of outreach are needed? J: I t ’s precisely because this kind of support group does ghettoize the issue that it feels manageable. -

Students' Perceptions of Lesbian and Gay Professors1

Inventing a Gay Agenda: Students’ Perceptions of Lesbian and Gay Professors1 Kristin J. Anderson2 and Melinda Kanner University of Houston–Downtown Students’ perceptions of lesbian and gay professors were examined in 2 studies (Ns = 622 and 545). An ethnically diverse sample of undergraduates read and responded to a syllabus for a proposed Psychology of Human Sexuality course. Syllabuses varied according to the political ideology, carefulness, sexual orientation, and gender of the professor. Students rated professors on dimensions such as politi- cal bias, professional competence, and warmth. Lesbian and gay professors were rated as having a political agenda, compared to heterosexual professors with the same syllabus. Student responses differed according to their homonegativity and modern homonegativity scores. The findings from these studies suggest that students may use different criteria to evaluate lesbian, gay, and heterosexual professors’ ability to approach courses objectively.jasp_757 1538..1564 Psychology has a rich history of research on prejudice against people of color in the United States, with recent work concentrating on subtle forms of racism. The work on subtle prejudice against other marginalized groups, such as lesbians and gay men, has received less scholarly attention (Whitley & Kite, 2010). Likewise, the experiences, evaluations, and perceptions of women and people of color in the academy have been subjects of research, but again, fewer studies have examined experimentally students’ perceptions and judgments of lesbian and gay professors. The academic environment in general, and the classroom in particular, are important environments to study discrimination against lesbian and gay professors. For professors, academia is a workplace in which their livelihoods and careers can be threatened with discrimination by students through course evaluations and by supervisors’ performance evaluations. -

Why Indiana Should Pass a Conversion Therapy Ban to Protect and Promote Mental Health Outcomes for Lgbtq Youth

EXTENDING HOOSIER HOSPITALITY TO LGBTQ YOUTH: WHY INDIANA SHOULD PASS A CONVERSION THERAPY BAN TO PROTECT AND PROMOTE MENTAL HEALTH OUTCOMES FOR LGBTQ YOUTH WARREN CANGANY* I. INTRODUCTION My sessions . focused on becoming a “proper woman.” I was told to become more submissive. I remember her saying, “It’s really a blessing we took you out of your leadership roles so guys will be more attracted to you.” The [other] woman focused on changing my physical appearance through feminine clothing and makeup. I soon developed an eating disorder: I don’t have a choice in attending these sessions, I thought, but at least I can control what I eat and throw up.1 Gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender youth, as well as adolescents questioning their gender identity, gender expression, or sexual orientation (“LGBTQ”) “experience significant health and behavioral health disparities. Negative social attitudes and discrimination related to an individual’s LGBTQ identity contribute to these disparities, and lead to individual stressors that affect mental health and well-being.”2 “Today’s LGBTQ youth face a variety of stressors – harassment, family and peer rejection, bullying from their peers, isolation and a lack of a sense of belonging – that have a major impact on their overall well-being.”3 Along with these challenges, LGBTQ youth also face the same age-related developments that accompany adolescence for all youth.4 These challenges include, but are not limited to, processing and expressing gender identity, romantic attraction, and physical changes experienced through puberty.5 However, unlike their heterosexual peers, LGBTQ youth must navigate * J.D. -

Reynold's Certain Aid^ Bill to Lead To

■ '(fCJ V R e m e m b e r School Grand Rrhe$ W ill Be Awarded Tomorrow ^ Avorage Daily CirenlatioB IT tin M«Mth o f jannary, I M l The Weather 1 rotaeaar ef S. Wau0M V. 6,626 « af the Audit ffk lr 'fe n liM and triday. niat a f CT'-rglatlrBie ■nch change fai 7* - ; . Manche$Ur~^'^City of Village Chahh V O L . LX .. NO . 121 an Paga U ) MANT^HESTER, C0NN„ THURSDAY, FEBRUARY-20,'1941 (POURTEBN PAGES) PRICE THREE CBNIB A rm y C h ief Italian Naval* Prisoners Leave ilam ing Tobruk i. l|Reynold’s Certain Aid^ Says Planes To Aid Navy t -i Bill to Lead to War; Unspecified dumber of f-i Latest Type to Rein- 4^ V,. I »■ > force Pacific Fleet; Need No Labor Curb Situation Is *Serious*, f Washington, Feb. 80.— — Gen. Hillman Says ^Strikes (IP) Convinced Enactment of George C Maraball, Army chief of Are Rare Exception in B a by Bonds Measure May Lead* ataff, was reported to have told the Senate Military Affairs Com Defense Industry' and United States Direct* mittee ‘ today that the United To Be Sold No Additional Legis- ly Toward Declara* Stateo Intends to reinforce the Paclflc fleet Immediately with an li^tion Necessary to tion; Calls It *Bill unapecifled number of the latest A s Taxable type o f Arm y and N avy fighting Deal with Them; La For Defenselof British planes. Declining to reveal, even in the bor and Management Empire at Expense Morgenthau Announces secret session of the committee, Praised for Work. -

Women's Studies in the History of Religions

1 Women’s Studies in the History of Religions DAVID KINSLEY On the most archaic levels of culture, living as a human being is in itself a religious act, for alimentation, sexual life, and work have a sacramental value. In other words, to be— or rather, to become—a man means to be “religious.” —Mircea Eliade, A History of Religious Ideas o appreciate the radical impact women’s studies has had on the discipline Tof history of religions, it is necessary first to describe briefly how the his- tory of religions understands its task. The history of religions, which claims to be the objective, scientific study of religion, sets as its task nothing less than the study, in historical and cross- cultural perspective, of all human religious phenomena. It includes in its pur- view, not only sophisticated, literate, philosophical, and theological materials, but also popular expressions of human religiosity such as festivals, life cycle rituals, myths, and practices that are found only in oral traditions. The history of religions seeks to avoid an approach to human religiosity that privileges cer- tain materials as “higher” and others as “lower.” It assumes that all expres- sions of human religiosity are worthy of study. In the words of Mircea Eliade: “For the historian of religions, every manifestation of the sacred is important: every rite, every myth, every belief or divine figure reflects the experience of the sacred and hence implies the notions of being, of meaning, and of truth.”1 History of religions does not seek to evaluate one religion (or religious expression) vis-à-vis another with a view to declaring one superior to the other. -

Download the Playbook

A Guide for Reporting SOUTHERN on LGBT People in STORIES South Carolina WE ARE A PROUD SPONSOR OF THE GLAAD SOUTHERN STORIES PROGRAM 800.789.5401 MGBWHOME.COM GLAAD Southern Stories A Guide for Reporting on LGBT People in South Carolina Getting Started 4 Terms and Definitions 5 South Carolina’s LGBT History 6 When GLAAD’s Accelerating Acceptance report revealed that levels of discomfort towards the LGBT community are as high as 43% in Terms to Avoid 10 America—and spike to 61% in the South—we knew we had to act. To accelerate LGBT acceptance in the U.S. South, GLAAD is telling the stories of LGBT people from across the region through our Southern Stories program. We are amplifying stories of LGBT people who are resilient in the face of inequality and Defamatory Language 11 adversity, and building a culture in which they are able not only to survive, but also to thrive. These are impactful stories with the power to change hearts and minds, but they are too often missed or ignored altogether. In South Carolina, the LGBT community is Best Practices in Media Coverage 12 making sure and steady progress, but the work to achieve full equality and acceptance is far from done. More and more, South Carolina sees communities of faith opening their arms to LGBT people; public officials listening to families, workers, and tax payers Pitfalls to Avoid as they voice their need for equal protections; 13 students creating supportive, inclusive spaces; and allies standing up for their LGBT friends, family members, and neighbors. -

Public Opinion and Discourse on the Intersection of LGBT Issues and Race the Opportunity Agenda

Opinion Research & Media Content Analysis Public Opinion and Discourse on the Intersection of LGBT Issues and Race The Opportunity Agenda Acknowledgments This research was conducted by Loren Siegel (Executive Summary, What Americans Think about LGBT People, Rights and Issues: A Meta-Analysis of Recent Public Opinion, and Coverage of LGBT Issues in African American Print and Online News Media: An Analysis of Media Content); Elena Shore, Editor/Latino Media Monitor of New America Media (Coverage of LGBT Issues in Latino Print and Online News Media: An Analysis of Media Content); and Cheryl Contee, Austen Levihn- Coon, Kelly Rand, Adriana Dakin, and Catherine Saddlemire of Fission Strategy (Online Discourse about LGBT Issues in African American and Latino Communities: An Analysis of Web 2.0 Content). Loren Siegel acted as Editor-at-Large of the report, with assistance from staff of The Opportunity Agenda. Christopher Moore designed the report. The Opportunity Agenda’s research on the intersection of LGBT rights and racial justice is funded by the Arcus Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are those of The Opportunity Agenda. Special thanks to those who contributed to this project, including Sharda Sekaran, Shareeza Bhola, Rashad Robinson, Kenyon Farrow, Juan Battle, Sharon Lettman, Donna Payne, and Urvashi Vaid. About The Opportunity Agenda The Opportunity Agenda was founded in 2004 with the mission of building the national will to expand opportunity in America. Focused on moving hearts, minds, and policy over time, the organization works with social justice groups, leaders, and movements to advance solutions that expand opportunity for everyone. Through active partnerships, The Opportunity Agenda synthesizes and translates research on barriers to opportunity and corresponding solutions; uses communications and media to understand and influence public opinion; and identifies and advocates for policies that improve people’s lives. -

Lawrence V. Texas

No. INTHE SUPREME COURT OF TIlE UNITED STATES JOHN GEDDES LAWRENCE AND TYRON GARNER, Petitioners, V. STATE OF TEXAS Respondent. On Petition For A Writ Of Certiorari To The Court Of Appeals Of Texas Fourteenth District PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI Paul M. Smith Ruth E. Harlow William M. Hohengarten Counsel of Record Daniel Mach Patricia M. Logue JENNER& BLOCK, LLC Susan L. Sommer 601 13th Street, N.W. LAMBDALEGALDEFENSE Washington, DC 20005 AND EDUCATION FUND, INC. (202) 639-6000 120 Wall Street, Suite 1500 New York, NY 10005 Mitchell Katine (212) 809-8585 WILLIAMS, BIRNBERG & ANDERSEN,L.L.P. 6671 Southwest Freeway, Suite 303 Houston, Texas 77074 (713) 981-9595 Counsel for Petitioners i QUESTIONS PRESENTED 1. Whether Petitioners' criminal convictions under the Texas "Homosexual Conduct" law - which criminalizes sexual intimacy by same-sex couples, but not identical behavior by different-sex couples - violate the Fourteenth Amendment guarantee of equal protection of the laws? 2. Whether Petitioners' criminal convictions for adult consensual sexual intimacy in the home violate their vital interests in liberty and privacy protected by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment? 3. Whether Bowers v. Hardwick, 478 U.S. 186 (1986), should be overruled? ii PARTIES Petitioners are John Geddes Lawrence and Tyron Garner. Respondent is the State of Texas. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE QUESTIONS PRESENTED ........................... i PARTIES ........................................... ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .......................... vi OPINIONS AND ORDERS BELOW ................... 1 JURISDICTION ..................................... 1 STATUTORY AND CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS .. 2 STATEMENT OF THE CASE ......................... 2 A. The Homosexual Conduct Law ............ 2 B. Petitioners' Arrests, Convictions, and Appeals ................................ 5 REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT .............. -

Final Version

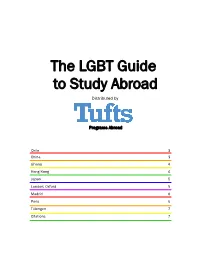

The LGBT Guide to Study Abroad Distributed by Programs Abroad Chile 3 China 3 Ghana 4 Hong Kong 4 Japan 5 London; Oxford 5 Madrid 6 Paris 6 Tübingen 7 Citations 7 Dear Student, The Pew Research Center conducted a world-wide survey between March and May of 2013 on the subject of homo- sexuality. They asked 37,653 participants in 39 countries, “Should society accept homosexuality?” The results, summariZed in this graphic, are revealing. There is a huge variance by region; some countries are extremely divided on the issue. Others have been, and continue to be, widely accepting of homosexuality. This information is relevant not only to residents of these countries, but to travelers and students who will be studying abroad. Students going abroad should be prepared for noted differences in attitudes toward individuals. Before depar- ture, it can be helpful for LGBT students to research cur- rent events pertaining to LGBT rights, general tolerance of LGBT persons, legal protection of LGBT individuals, LGBT organizations and support systems, and norms in the host culture’s dating scene. We hope that the following summaries will provide a starting point for the LGBT student’s exploration of their destination’s culture. If students are in homestay situations, they should consider the implications of coming out to their host family. Students may choose to conceal their sexual orientation to avoid tension in the student-host family relationship. Other times, students have used their time away from their home culture as an opportunity to come out. Some students have even described coming out overseas as a liberating experience, akin to a “second” coming out.