Transport Statistics Great Britain 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Empire and English Nationalismn

Nations and Nationalism 12 (1), 2006, 1–13. r ASEN 2006 Empire and English nationalismn KRISHAN KUMAR Department of Sociology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, USA Empire and nation: foes or friends? It is more than pious tribute to the great scholar whom we commemorate today that makes me begin with Ernest Gellner. For Gellner’s influential thinking on nationalism, and specifically of its modernity, is central to the question I wish to consider, the relation between nation and empire, and between imperial and national identity. For Gellner, as for many other commentators, nation and empire were and are antithetical. The great empires of the past belonged to the species of the ‘agro-literate’ society, whose central fact is that ‘almost everything in it militates against the definition of political units in terms of cultural bound- aries’ (Gellner 1983: 11; see also Gellner 1998: 14–24). Power and culture go their separate ways. The political form of empire encloses a vastly differ- entiated and internally hierarchical society in which the cosmopolitan culture of the rulers differs sharply from the myriad local cultures of the subordinate strata. Modern empires, such as the Soviet empire, continue this pattern of disjuncture between the dominant culture of the elites and the national or ethnic cultures of the constituent parts. Nationalism, argues Gellner, closes the gap. It insists that the only legitimate political unit is one in which rulers and ruled share the same culture. Its ideal is one state, one culture. Or, to put it another way, its ideal is the national or the ‘nation-state’, since it conceives of the nation essentially in terms of a shared culture linking all members. -

Emigration from Great Britain

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: International Migrations, Volume II: Interpretations Volume Author/Editor: Walter F. Willcox, editor Volume Publisher: NBER Volume ISBN: 0-87014-017-5 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/will31-1 Publication Date: 1931 Chapter Title: Emigration from Great Britain Chapter Author: C. E. Snow Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c5111 Chapter pages in book: (p. 237 - 260) PART III STUDIES OF NATIONALEMIGRATION CURRENTS CHAPTER IX EMIGRATION FROM GREAT BRITAIN.' By DR. C. E. SNOW. General Concerning emigration from Great Britain prior to 1815, only fragmentary statistics are available, for before that date no regular attempt was made to measure the outflow of population.For some years before the treaty of peace with France, under which Canada in 1763 became a colony of the United Kingdom, a certain number of emigrants from Great Britain to the British North Amer- ican colonies were reported, but no reliable figures are available. During the five years 1769—1774 there was an emigration, probably approaching 10,000 persons per annum,2 from Scotland to North America, and substantial numbers also left England for the same destination.It has been estimated by Johnson3 that during the first decade of the nineteenth century the annual emigration from the whole of the United Kingdom to the American Continent ex- ceeded 20,000 persons, the majority going from the Highlands of Scotland and from Ireland. Emigration can be considered from two distinct aspects: (a) from the point of view of the force attracting people to other countries; (b) from the point of view of the force expelling people from their own country. -

H 955 Great Britain

Great Britain H 955 BACKGROUND: The heading Great Britain is used in both descriptive and subject cataloging as the conventional form for the United Kingdom, which comprises England, Northern Ireland, Scotland, and Wales. This instruction sheet describes the usage of Great Britain, in contrast to England, as a subject heading. It also describes the usage of Great Britain, England, Northern Ireland, Scotland, and Wales as geographic subdivisions. 1. Great Britain vs. England as a subject heading. In general assign the subject heading Great Britain, with topical and/or form subdivisions, as appropriate, to works about the United Kingdom as a whole. Assign England, with appropriate subdivision(s), to works limited to that country. Exception: Do not use the subdivisions BHistory or BPolitics and government under England. For a work on the history, politics, or government of England, assign the heading Great Britain, subdivided as required for the work. References in the subject authority file reflect this practice. Use the subdivision BForeign relations under England only in the restricted sense described in the scope note under EnglandBForeign relations in the subject authority file. 2. Geographic subdivision. a. Great Britain. Assign Great Britain directly after topics for works that discuss the topic in relation to Great Britain as a whole. Example: Title: History of the British theatre. 650 #0 $a Theater $z Great Britain $x History. b. England, Scotland, Northern Ireland, and Wales. Assign England, Scotland, Northern Ireland, or Wales directly after topics for works that limit their discussion to the topic in relation to one of the four constituent countries of Great Britain. -

Background, Brexit, and Relations with the United States

The United Kingdom: Background, Brexit, and Relations with the United States Updated April 16, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL33105 SUMMARY RL33105 The United Kingdom: Background, Brexit, and April 16, 2021 Relations with the United States Derek E. Mix Many U.S. officials and Members of Congress view the United Kingdom (UK) as the United Specialist in European States’ closest and most reliable ally. This perception stems from a combination of factors, Affairs including a sense of shared history, values, and culture; a large and mutually beneficial economic relationship; and extensive cooperation on foreign policy and security issues. The UK’s January 2020 withdrawal from the European Union (EU), often referred to as Brexit, is likely to change its international role and outlook in ways that affect U.S.-UK relations. Conservative Party Leads UK Government The government of the UK is led by Prime Minister Boris Johnson of the Conservative Party. Brexit has dominated UK domestic politics since the 2016 referendum on whether to leave the EU. In an early election held in December 2019—called in order to break a political deadlock over how and when the UK would exit the EU—the Conservative Party secured a sizeable parliamentary majority, winning 365 seats in the 650-seat House of Commons. The election results paved the way for Parliament’s approval of a withdrawal agreement negotiated between Johnson’s government and the EU. UK Is Out of the EU, Concludes Trade and Cooperation Agreement On January 31, 2020, the UK’s 47-year EU membership came to an end. -

English Society 1660±1832

ENGLISH SOCIETY 1660±1832 Religion, ideology and politics during the ancien regime J. C. D. CLARK published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, UK www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011±4211, USA www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia Ruiz de AlarcoÂn 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain # Cambridge University Press 2000 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published as English Society 1688±1832,1985. Second edition, published as English Society 1660±1832 ®rst published 2000. Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Baskerville 11/12.5 pt. System 3b2[ce] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Clark, J. C. D. English society, 1660±1832 : religion, ideology, and politics during the ancien regime/J.C.D.Clark. p. cm. Rev. edn of: English society, 1688±1832. 1985. Includes index. isbn 0 521 66180 3 (hbk) ± isbn 0 521 66627 9 (pbk) 1. Great Britain ± Politics and government ± 1660±1714. 2. Great Britain ± Politics and government ± 18th century. 3. Great Britain ± Politics and government ± 1800±1837. 4. Great Britain ± Social conditions. i.Title. ii.Clark,J.C.D.Englishsociety,1688±1832. -

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland Is Situated on the British Isles

Дата: 15.10.2020 Группа: 102Фк Специальность: Лечебное дело Тема: The United Kingdom. England. Scotland. Задание лекции: перевести слова под текстом. Домашнее задание – найти: 1) Столицы стран Великобритании 2) Символы стран Великобритании 3) Флаги стран Великобритании 4) Национальные блюда стран Великобритании The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is situated on the British Isles. The British Isles consist of two large islands, Great Britain and Ireland, and about five thousands small islands. Their total area is over 244 000 square kilometres. The United ingdom is one o! the world"s smaller #ountries. Its population is over $% million. &bout '0 (er#ent o! the (o(ulation is urban. The United ingdom is made up of !our #ountries) *ngland, +ales, ,#otland and -orthern Ireland. Their #a(itals are .ondon, /ardi0, *dinburgh and Bel!ast res(e#tivel1. Great Britain #onsists o! *ngland, ,#otland and +ales and does not include -orthern Ireland. But in everyday s(ee#h 2Great Britain» is used in the meaning o! the 2United ingdom o! Great Britain and -orthern Ireland3. The #a(ital o! the U is .ondon. The British Isles are separated from the /ontinent by the -orth ,ea, the *nglish /hannel and the ,trait o! 4over. The western #oast o! Great Britain is washed by the &tlanti# 5#ean and the Irish ,ea. The surface o! the British Isles varies very mu#h. The north o! ,#otland is mountainous and is #alled 6ighlands. The south, whi#h has beauti!ul valleys and plains, is #alled .owlands. The north and west o! *ngland are mountainous, but the eastern, #entral and south-eastern (arts o! *ngland are a vast (lain. -

The Development of the Railway Network in Britain 1825-19111 Leigh Shaw-Taylor and Xuesheng You 1

The development of the railway network in Britain 1825-19111 Leigh Shaw-Taylor and Xuesheng You 1. Introduction This chapter describes the development of the British railway network during the nineteenth century and indicates some of its effects. It is intended to be a general introduction to the subject and takes advantage of new GIS (Geographical Information System) maps to chart the development of the railway network over time much more accurately and completely than has hitherto been possible. The GIS dataset stems from collaboration by researchers at the University of Cambridge and a Spanish team, led by Professor Jordi Marti-Henneberg, at the University of Lleida. Our GIS dataset derives ultimately from the late Michael Cobb’s definitive work ‘The Railways of Great Britain. A Historical Atlas’. Our account of the development of the British railway system makes no pretence at originality, but the chapter does present some new findings on the economic impact of the railways that results from a project at the University of Cambridge in collaboration with Professor Dan Bogart at the University of California at Irvine.2 Data on railway developments in Scotland are included but we do not discuss these in depth as they fell outside the geographical scope of the research project that underpins this chapter. Also, we focus on the period up to 1911, when the railway network grew close to its maximal extent, because this was the end date of our research project. The organisation of the chapter is as follows. The next section describes the key characteristics of the British transport system before the coming of the railways in the nineteenth century. -

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland: Great Britain

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland: Great Britain Basic Facts: . The “United Kingdom” includes Great Britain (England, Scotland, Wales) and Northern Ireland. Great Britain and Northern Ireland are the two main islands of the United Kingdom. The national capital is London. The flag of the UK represents England, Northern Scotland, the flag of Great Britain, and Northern Ireland. This is sometimes confusing. Let’s look at some different names that are sometimes confused: o England = ___________________ o Britain= ______________________ + __________________ o Great Britain= ________________ + __________________+___________________ o United Kingdom= _____________ +___________________+ _________________+__________________ . In addition to Great Britain and Northern Ireland, the United Kingdom has many small islands. It also has many territories around the world that may not officially be considered part of the United Kingdom but do have a special relationship with the British government. Weather: Great Britain experiences plenty of rainfall, and the weather is often changeable and difficult to predict. Because of this, weather is often a topic for discussion. Because of the abundant rainfall and mild climate, Britain is great environment for plants to grow and is very green. Language: English is the official language for the entire United Kingdom, but some people speak it in different ways, influenced by their family history. (Welsh English, Scottish English, etc.) Other Nationalities: The United Kingdom contains people from many countries. These immigrants sometimes live in communities with other immigrants from the same area. As of 1998, there were 170,000 Chinese living in Britain, mostly from Hong Kong. 1/3 of those Chinese were living in London at the time. -

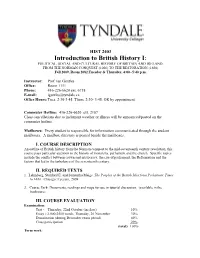

Introduction to British History I

HIST 2403 Introduction to British History I: POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL HISTORY OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND, FROM THE NORMAN CONQUEST (1066) TO THE RESTORATION (1660) Fall 2009, Room 2082,Tuesday & Thursday, 4:00--5:40 p.m. Instructor: Prof. Ian Gentles Office: Room 1111 Phone: 416-226-6620 ext. 6718 E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Tues. 2:30-3:45, Thurs. 2:30- 3:45, OR by appointment Commuter Hotline: 416-226-6620 ext. 2187 Class cancellations due to inclement weather or illness will be announced/posted on the commuter hotline. Mailboxes: Every student is responsible for information communicated through the student mailboxes. A mailbox directory is posted beside the mailboxes. I. COURSE DESCRIPTION An outline of British history from the Norman conquest to the mid-seventeenth century revolution, this course pays particular attention to the history of monarchy, parliament and the church. Specific topics include the conflict between crown and aristocracy, the rise of parliament, the Reformation and the factors that led to the turbulence of the seventeenth century. II. REQUIRED TEXTS 1. Lehmberg, Stanford E. and Samantha Meigs. The Peoples of the British Isles from Prehistoric Times to 1688 . Chicago: Lyceum, 2009 2. Course Pack: Documents, readings and maps for use in tutorial discussion. (available in the bookstore) III. COURSE EVALUATION Examination : Test - Thursday, 22nd October (in class) 10% Essay - 2,000-2500 words, Thursday, 26 November 30% Examination (during December exam period) 40% Class participation 20% (total) 100% Term work : a. You are expected to attend the tutorials, preparing for them through the lectures and through assigned reading. -

The Expansion of England? Rethinking Scotland's Place in The

The expansion of England? Rethinking Scotland’s place in the architectural history of the wider British world G. A. Bremner The principal title of this essay may be taken as a conceit. But it highlights a basic misconstruction that has plagued the political understanding of the British Isles for centuries. It comes from J. R. Seeley’s popular account of the British Empire published in the early 1880s, entitled precisely that, The Expansion of England.1 Although Seeley refers to ‘England’ throughout the book, it is clear he is describing what had become by 1707 the nation state of Britain, or more precisely Great Britain (United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland after 1801). This constant if not stubborn reference to England by Seeley would seem all the more peculiar given that the critical moments of success for the empire in his account are seen to begin with the eighteenth century. Why he refers to England alone is not clear. It might be that he viewed ‘the empire’ as originally, and thus ultimately, an English invention; or simply that the idea of ‘England’ (and its compound referents) was taken for granted as signifying Britain in the minds of his contemporaries.2 Consequently, to the modern reader, there remains a fundamental confusion at the heart of the book’s narrative when, in a single sentence, Seeley can talk of England and then ‘Greater Britain’ without qualification, as if his readers were naturally capable of making this conceptual leap. Seeley was of course not the only one to conflate England with the idea of Britain, or to lump the Scots and the Welsh, let alone the Irish, in with the idea of Englishness.3 After all, one of the proudest and most famous Scots of all, David Livingstone, was prone to 1 J. -

J E Lloyd and the Intellectual Foundations of Welsh History : Emyr

J E Lloyd and the intellectual foundations of Welsh history 1 J E Lloyd’s ‘A History of Wales from the Earliest Times to the Edwardian Conquest’ first published in 1911, has been of central importance to the development of Welsh historiography. This article seeks to assess the validity of the model of Welsh history developed by Lloyd. Initially, his nurturing within the Oxford school of Germanist historians, a school of thought which placed great weight on the importance of race, is considered. Lloyd is then identified as seeking to establish a complementary Welsh school of Brythonic historians. In developing his historical model he not only misinterpreted the archaeological and written records, but also suppressed evidence of the extent to which ‘Wales’ had been assimilated into the Roman Empire. He was able to sustain his model in both the first (1911) and second (1912) editions of his ‘History of Wales’, but by the time the third edition was published in 1939 that was no longer possible. Advances in the understanding of the archaeological record and the discrediting of race as a basis for historical analysis meant that the earlier foundations to his work were too contentious. As a consequence, in 1939 Lloyd abandoned that earlier theoretical framework, and sought to establish a new basis for his work. Whether he replaced those foundations with an appropriate alternative is an issue which has never been satisfactorily addressed by Welsh historians. It is suggested that consideration of that issue could prove advantageous to Welsh History in the contemporary context. In the introduction to his History of Wales, J E Lloyd 2 presented the following account of his approach to the writing of Welsh history: … (I)t has been my endeavour to bring together and to weave into a continuous narrative what may be fairly regarded as the ascertained facts of the history of Wales up to the fall of Llywelyn ap Gruffydd in 1282. -

England-Chapter-1.Pdf

MACMILLAN CULTURAL READERS PRE-INTERMEDIATE LEVEL RACHEL BLADON England MACMILLAN 1 A Short History PH??.? Photo of a section of Hadrian’s Wall. A view which emphasises the size of it. Hadrian’s Wall, built by the Romans Back in England’s oldest times, people lived in big groups called tribes. They were farmers – they grew their food, and kept animals for meat and eggs. They lived in villages, in wooden or mud4 houses, and there was often fighting between the different tribes. Life was simple but dangerous. Then in AD 43, forty thousand Roman soldiers invaded5 England from the area of Europe that is now Italy. The Roman army was very well-organized and had good weapons6. The soldiers built a wall around themselves every night so they were safe. They moved across the country, fighting and winning battles7 against the different tribes, and after four years they controlled8 the south of England. The Romans had to fight for many years before they controlled all of England. They made many changes in the country, such as building towns and cities, and good roads. They brought a new language to England – Latin – and made laws, so people knew what they could and could not do. The religion9 of Christianity came to England in Roman times too. 7 1 The Romans never took control of P Scotland, which is north of England, and Scottish tribes came to fight against them in the north of England again and again. Because of this, in the second century AD, the Romans built a wall to stop the Scottish tribes coming to England.