The Story of the Melbourne Citylink

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City Link's High-Speed Electronic Tolling

CASE PROGRAM 2007-91.1 City Link’s high-speed electronic tolling (A) The tolling systems went live without a glitch at 1 am Monday the 3rd [of January 2000], a national public holiday. Charges now apply at three toll points located at the Tullamarine section, the elevated roadway between Racecourse and Dynon Roads, and the Bolte Bridge… Although fewer motorists were on the road, demand for e-Tags was strong. Since the 23 December announcement [that tolling would begin 3 January] more than 45,000 e-Tags have been ordered, bringing the total sales to date to almost 400,000. The first day of tolling, CityLink’s 132629 hotline fielded more than 20,000 calls. The continued demand throughout the week prompted Transurban to announce the availability of a second hotline for general enquiries… Transurban Managing Director Kim Edwards said the company was pleased with the recent developments and expressed appreciation for the public’s patience during recent delays. “We are thrilled to deliver the completed Western Link to Melbourne’s motorists, who will now get the full benefit of the project’s leading-edge technology and design,” he said. Extract from: fasttrack, Transurban CityLink executive information newsletter, January 2000. In August 2000, Transurban City Link chief executive Kim Edwards announced that his company’s damages claim against the consortium Transfield-Obayashi Joint Venture (TOJV) for delays and difficulties with the 22-km City Link tollway was ________________________________________________________________ This case was prepared from published information by Susan Keyes-Pearce, MBA 1998 and Professor Michael Vitale of the Centre for Management of Information Technology at the University of Melbourne. -

Citylink Groundwater Management

CASE STUDY CityLink Groundwater Management Aquifer About CityLink Groundwater implications for design and construction A layer of soil or rock with relatively higher porosity CityLink is a series of toll-roads that connect major and permeability than freeways radiating outward from the centre of Design of tunnels requires lots of detailed surrounding layers. This Melbourne. It involved the upgrading of significant geological studies to understand the materials that enables usable quantities stretches of existing freeways, the construction of the tunnel will be excavated through and how those of water to be extracted from it. new roads including a bridge over the Yarra River, materials behave. The behavior of the material viaducts and two road tunnels. The latter are and the groundwater within it impacts the design of Fault zone beneath residential areas, the Yarra River, the the tunnel. A challenge for design beneath botanical gardens and sports facilities where surface suburbs and other infrastructure is getting access A area of rock that has construction would be either impossible or to sites to get that information! The initial design of been broken up due to stress, resulting in one unacceptable. the tunnel was based on assumptions of how much block of rock being groundwater would flow into the tunnel, and how displaced from the other. The westbound Domain tunnel is approximately much pressure it would apply on the tunnel walls They are often associated 1.6km long and is shallow. The east-bound Burnley (Figure 2). with higher permeability than the surrounding rock tunnel is 3.4km long part of which is deep beneath the Yarra River. -

A 'Common-Sense Revolution'? the Transformation of the Melbourne City

A ‘COMMON-SENSE REVOLUTION’? THE TRANSFORMATION OF THE MELBOURNE CITY COUNCIL, 1992−9 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy April, 2015 Angela G. Munro Faculty of Business, Government and Law Institute for Governance and Policy Analysis University of Canberra ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis is the culmination of almost fifty years’ interest professionally and as a citizen in local government. Like many Australians, I suspect, I had barely noticed it until I lived in England where I realised what unique attributes it offered, despite the different constitutional arrangements of which it was part. The research question of how the disempowerment and de-democratisation of the Melbourne City Council from 1992−9 was possible was a question with which I had wrestled, in practice, as a citizen during those years. My academic interest was piqued by the Mayor of Stockholm to whom I spoke on November 18, 1993, the day on which the Melbourne City Council was sacked. ‘That couldn’t happen here’, he said. I have found the project a herculean labour, since I recognised the need to go back to 1842 to track the institutional genealogy of the City Council’s development in the pre- history period to 1992 rather than a forensic examination of the seven year study period. I have been exceptionally fortunate to have been supervised by John Halligan, Professor of Public Administration at University of Canberra. An international authority in the field, Professor Halligan has published extensively on Australian systems of government including the capital cities and the Melbourne City Council in particular. -

Upholding the Australian Constitution Volume Nineteen

Chapter Six The Politics of Federalism Ben Davies In 1967 Sir Robert Menzies published Central Power in the Australian Commonwealth. In this book he adopted the labels coined by Lord Bryce to describe the two forces which operate in a federation—the centripetal and the centrifugal. For those uneducated in physics, such as myself, centripetal means those forces which draw power towards the centre, or the Commonwealth, whilst centrifugal forces are those which draw power outwards towards the States. Menzies remarked that these forces are constantly competing against each other, and that the balance between them is never static.1 Not surprisingly, his view in 1967 was that the centripetal forces had well and truly predominated during the previous 66 years of Federation. Of course, he would not need long to reach the same conclusion were he to consider the same question now, 40 years later. Essentially there are three levels on which these two forces exert themselves. The first and most fundamental is the legal level, which describes the constitutional structures which determine the federal balance. On questions of federalism this Society has since its inception quite rightly concentrated most on this level of federalism, as it is at this level that the most profound changes have occurred. It is also the most influential level, as it sets the boundaries within which the other two levels can operate. The second level is what I would call the financial level, and this level concerns itself with the question of the relative financial powers of the States and Commonwealth. In particular, this level is characterised by the ever-increasing financial dominance of the Commonwealth relative to the States, and the “vertical fiscal imbalance” with which the States have had to contend for most of their existence since Federation. -

Letter from Melbourne Is a Monthly Public Affairs Bulletin, a Simple Précis, Distilling and Interpreting Mother Nature

SavingLETTER you time. A monthly newsletter distilling FROM public policy and government decisionsMELBOURNE which affect business opportunities in Australia and beyond. Saving you time. A monthly newsletter distilling public policy and government decisions which affect business opportunities in Australia and beyond. p11-14: Special Melbourne Opera insert Issue 161 Our New Year Edition 16 December 2010 to 13 January 2011 INSIDE Auditing the state’s affairs Auditor (VAGO) also busy Child care and mental health focus Human rights changes Labor leader no socialist. Myki musings. Decision imminent. Comrie leads Victorian floods Federal health challenge/changes And other big (regional) rail inquiry HealthSmart also in the news challenge Baillieu team appointments New water minister busy Windsor still in the news 16 DECEMBER 2010 to 13 JANUARY 2011 14 Collins Street EDITORIAL Melbourne, 3000 Victoria, Australia Our government warming up. P 03 9654 1300 Even some supporters of the Baillieu government have commented that it is getting off to a slow F 03 9654 1165 start. The fact is that all ministers need a chief of staff and specialist and other advisers in order to [email protected] properly interface with the civil service, as they apply their new policies and different administration www.letterfromcanberra.com.au emphases. These folk have to come from somewhere and the better they are, the longer it can take for them to leave their current employment wherever that might be and settle down into a government office in Melbourne. Editor Alistair Urquhart Some stakeholders in various industries are becoming frustrated, finding it difficult to get the Associate Editor Gabriel Phipps Subscription Manager Camilla Orr-Thomson interaction they need with a relevant minister. -

Domain Parklands Master Plan 2019-2039 a City That Cares for the Environment

DOMAIN PARKLANDS MASTER PLAN 2019-2039 A CITY THAT CARES FOR THE ENVIRONMENT Environmental sustainability is the basis of all Future Melbourne goals. It requires current generations to choose how they meet their needs without compromising the ability of future generations to be able to do the same. Acknowledgement of Traditional Owners The City of Melbourne respectfully acknowledges the Traditional Owners of the land, the Boon Wurrung and Woiwurrung (Wurundjeri) people of the Kulin Nation and pays respect to their Elders, past and present. For the Kulin Nation, Melbourne has always been an important meeting place for events of social, educational, sporting and cultural significance. Today we are proud to say that Melbourne is a significant gathering place for all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. melbourne.vic.gov.au CONTENTS A City That Cares For Its Environment 2 4. Master Plan Themes 23 1. Overview 5 4.1 Nurture a diverse landscape and parkland ecology 23 1.1 Why do we need a master plan? 6 4.2 Acknowledge history and cultural heritage 24 1.2 Vision 7 4.3 Support exceptional visitor experience 28 1.3 Domain Parklands Master Plan Snapshot 8 4.4 Improve people movement and access 32 1.4 Preparation of the master plan 9 4.5 Management and partnerships to build resilience 39 1.5 Community and Stakeholder engagement 10 5. Domain Parklands Precincts Plans 41 2. Domain Parklands 11 5.1 Precinct 1 - Alexandra and Queen Victoria Gardens 42 2.1 The history of the site 11 5.2 Precinct 2 - Kings Domain 43 2.2 The Domain Parklands today 12 5.3 Precinct 3 - Yarra Frontage and Government House 44 2.3 Strategic context and influences 12 5.4 Precinct 4 - Visitor Precinct 45 2.4 Landscape Characters 14 5.5 Precinct 5 - Kings Domain South 46 2.5 Land management and status 15 6. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FIFTY-FIFTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION 9 April 2003 (extract from Book 4) Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor JOHN LANDY, AC, MBE The Lieutenant-Governor Lady SOUTHEY, AM The Ministry Premier and Minister for Multicultural Affairs ....................... The Hon. S. P. Bracks, MP Deputy Premier, Minister for Environment, Minister for Water and Minister for Victorian Communities.............................. The Hon. J. W. Thwaites, MP Minister for Finance and Minister for Consumer Affairs............... The Hon. J. Lenders, MLC Minister for Education Services and Minister for Employment and Youth Affairs....................................................... The Hon. J. M. Allan, MP Minister for Transport and Minister for Major Projects................ The Hon. P. Batchelor, MP Minister for Local Government and Minister for Housing.............. The Hon. C. C. Broad, MLC Treasurer, Minister for Innovation and Minister for State and Regional Development......................................... The Hon. J. M. Brumby, MP Minister for Agriculture........................................... The Hon. R. G. Cameron, MP Minister for Planning, Minister for the Arts and Minister for Women’s Affairs................................... The Hon. M. E. Delahunty, MP Minister for Community Services.................................. The Hon. S. M. Garbutt, MP Minister for Police and Emergency Services and -

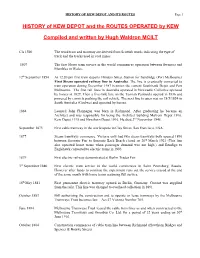

__History of Kew Depot and It's Routes

HISTORY OF KEW DEPOT AND ITS ROUTES Page 1 HISTORY of KEW DEPOT and the ROUTES OPERATED by KEW Compiled and written by Hugh Waldron MCILT CA 1500 The word tram and tramway are derived from Scottish words indicating the type of truck and the tracks used in coal mines. 1807 The first Horse tram service in the world commences operation between Swansea and Mumbles in Wales. 12th September 1854 At 12.20 pm first train departs Flinders Street Station for Sandridge (Port Melbourne) First Steam operated railway line in Australia. The line is eventually converted to tram operation during December 1987 between the current Southbank Depot and Port Melbourne. The first rail lines in Australia operated in Newcastle Collieries operated by horses in 1829. Then a five-mile line on the Tasman Peninsula opened in 1836 and powered by convicts pushing the rail vehicle. The next line to open was on 18/5/1854 in South Australia (Goolwa) and operated by horses. 1864 Leonard John Flannagan was born in Richmond. After graduating he became an Architect and was responsible for being the Architect building Malvern Depot 1910, Kew Depot 1915 and Hawthorn Depot 1916. He died 2nd November 1945. September 1873 First cable tramway in the world opens in Clay Street, San Francisco, USA. 1877 Steam tramways commence. Victoria only had two steam tramways both opened 1890 between Sorrento Pier to Sorrento Back Beach closed on 20th March 1921 (This line also operated horse trams when passenger demand was not high.) and Bendigo to Eaglehawk converted to electric trams in 1903. -

North Melbourne Station Melbourne

2 North Melbourne Station Melbourne e c T r e t s n u M t S Victoria St h g t t r t S S t S u S n l d b V l ic to r a ria i S n e y t o f r h o w t s s t a r D o t o L e S b d b n A A Silk P L l a Miller St u r e n s Spe S nce t r S Miller St R t a i t lw S a l y l P e l w a Dy d t non R S 2 NORTH MELBOURNE t S h g r u b y r D Ire lan d S t Pl s t k S ic d r D o f s t o b b T A a i t L a ne e A n dd a er L ley it S a t T t S e k w a H e n a L n e d d a M R a i lw t a S y n e P d l o R 0 50 100 200 300 Mtetres Image © Data source: DEDJTR, Aerial Imagery, 2015. Vicmap DELWP, Data, 2015 S Fo ey ot nl North Melbournesc Station opened in 1859 and is a ta ray S 0 50 Rd100 200 300 major interchange station servicing the Craigieburn,Metres Flemington Racecourse, Sunbury, Upfield, Werribee Document Path: G:\31\33036\GIS\Maps\Working\31-33036_001_OtherStationSiteFootprints300mAerial_20cm.mxd and Williamstown lines. -

Victoria Harbour Docklands Conservation Management

VICTORIA HARBOUR DOCKLANDS CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN VICTORIA HARBOUR DOCKLANDS Conservation Management Plan Prepared for Places Victoria & City of Melbourne June 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS xi PROJECT TEAM xii 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Background and brief 1 1.2 Melbourne Docklands 1 1.3 Master planning & development 2 1.4 Heritage status 2 1.5 Location 2 1.6 Methodology 2 1.7 Report content 4 1.7.1 Management and development 4 1.7.2 Background and contextual history 4 1.7.3 Physical survey and analysis 4 1.7.4 Heritage significance 4 1.7.5 Conservation policy and strategy 5 1.8 Sources 5 1.9 Historic images and documents 5 2.0 MANAGEMENT 7 2.1 Introduction 7 2.2 Management responsibilities 7 2.2.1 Management history 7 2.2.2 Current management arrangements 7 2.3 Heritage controls 10 2.3.1 Victorian Heritage Register 10 2.3.2 Victorian Heritage Inventory 10 2.3.3 Melbourne Planning Scheme 12 2.3.4 National Trust of Australia (Victoria) 12 2.4 Heritage approvals & statutory obligations 12 2.4.1 Where permits are required 12 2.4.2 Permit exemptions and minor works 12 2.4.3 Heritage Victoria permit process and requirements 13 2.4.4 Heritage impacts 14 2.4.5 Project planning and timing 14 2.4.6 Appeals 15 LOVELL CHEN i 3.0 HISTORY 17 3.1 Introduction 17 3.2 Pre-contact history 17 3.3 Early European occupation 17 3.4 Early Melbourne shipping and port activity 18 3.5 Railways development and expansion 20 3.6 Victoria Dock 21 3.6.1 Planning the dock 21 3.6.2 Constructing the dock 22 3.6.3 West Melbourne Dock opens -

Victoria Government Gazette No

Victoria Government Gazette No. S 207 Friday 22 December 2000 By Authority. Victorian Government Printer SPECIAL Melbourne City Link Act 1995 NOTICE UNDER SECTION 71(1) Under section 71(1)(a) of the Melbourne City Link Act 1995 (Òthe ActÓ), Transurban City Link Limited ABN 65 070 810 678 (the relevant corporation in relation to the Link road) specifies the following toll zones on the Link road: Toll Zone Area on the Link road 4 That part of the Link road being the Domain Tunnel and that part of the Link road leading into that Tunnel between the eastern portal of that Tunnel and Punt Road, other than that part of the Link road - (a) being the eastbound carriageways of the Link road; (b) between Punt Road and the exit to Boulton Parade; and (c) comprising Boulton Parade. 5 That part of the Link road being the Burnley Tunnel and that part of the Link road leading out of that Tunnel between the eastern portal of that Tunnel and Burnley Street. 6 That part of the Link road being the eastbound carriageways between Punt Road and Burnley Street other than that part of the Link road being the Burnley Tunnel and that part of the Link road leading out of that Tunnel between the eastern portal of that Tunnel and Burnley Street. 7 That part of the Link road between Burnley Street and Punt Road and including that part of the Link roadÑ (a) between Punt Road and the exit to Boulton Parade, other than the eastbound carriageways; and (b) comprising Boulton Parade, other than: (i) the eastbound carriageways between Burnley Street and Punt Road; and (ii) that part of the Link road being the Burnley Tunnel and that part of the Link road leading out of that Tunnel between the eastern portal of that Tunnel and Burnley Street. -

East-West Road Travel 32 L Investing in Transport - Overview

31 l east-west road travel 32 l investing in transport - overview Travel patterns in Melbourne are changing. More and more The EWLNA has found that: people are travelling to and from the central city during peak • There is substantial demand for cross city travel, with periods; more people are moving around the city outside these particularly strong growth in travel from the west to the east periods; and more people are making trips across the city. and south-east. The combined impact of these trips is higher traffi c volumes and greater congestion on roads in the city’s inner and middle • Transport options for travel across the city are seriously suburbs, as well as signifi cant bottlenecks on both the road and congested. rail networks. • While the Monash-CityLink-West Gate freeway upgrade will The EWLNA has found a strong and growing demand for relieve pressure along this corridor, the extra capacity being east-west road travel in Melbourne – a demand that existing provided on the route will be fully taken up during peak infrastructure will be unable to meet without a very substantial periods within a relatively short time. increase in congestion. • With the exception of the Monash-CityLink-West Gate Modelling undertaken for the EWLNA confi rms what every freeway, the east-west roads within the EWLNA Study Area person travelling across Melbourne knows: that the increasing are disconnected and poorly suited to effi ciently moving high demand for travel, the escalating urban freight task and the volumes of traffi c across the city. growing number of cars on Melbourne’s roads are generating • Congestion on key east-west routes – and the accompanying greater levels of congestion on major cross city routes.