Upholding the Australian Constitution Volume Nineteen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drug Law Reform: Beyond Prohibition

THE AUSTRALIA INSTITUTE Drug Law Reform Beyond Prohibition Andrew Macintosh Discussion Paper Number 83 February 2006 ISSN 1322-5421 ii © The Australia Institute. This work is copyright. It may be reproduced in whole or in part for study or training purposes only with the written permission of the Australia Institute. Such use must not be for the purposes of sale or commercial exploitation. Subject to the Copyright Act 1968, reproduction, storage in a retrieval system or transmission in any form by any means of any part of the work other than for the purposes above is not permitted without written permission. Requests and inquiries should be directed to the Australia Institute. The Australia Institute iii Table of Contents Tables and Figures v Acknowledgements vi Summary vii 1. Introduction 1 2. Definitional and conceptual issues 4 2.1 What is a drug? 4 2.2 Licit and illicit drugs 4 2.3 Classifying psychoactive drugs 4 2.4 Other useful drug terms 5 2.5 What legislative options exist for drugs? 7 2.6 What do the terms ‘decriminalisation’ and ‘legalisation’ mean? 8 2.7 Diversion programs 9 3. A brief history of Australia’s drug laws 13 4. The theory behind Australia’s drug laws 23 4.1 Why have strict drug laws? 23 4.2 Reducing negative externalities and overcoming market failure 23 4.3 Reducing harm to individuals 28 4.4 Promoting and protecting moral values 30 5. Flaws in the strict prohibition approach 33 5.1 The direct costs of prohibition 33 5.2 The indirect costs of prohibition 34 6. -

Inaugural Speeches in the NSW Parliament Briefing Paper No 4/2013 by Gareth Griffith

Inaugural speeches in the NSW Parliament Briefing Paper No 4/2013 by Gareth Griffith ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The author would like to thank officers from both Houses for their comments on a draft of this paper, in particular Stephanie Hesford and Jonathan Elliott from the Legislative Assembly and Stephen Frappell and Samuel Griffith from the Legislative Council. Thanks, too, to Lenny Roth and Greig Tillotson for their comments and advice. Any errors are the author’s responsibility. ISSN 1325-5142 ISBN 978 0 7313 1900 8 May 2013 © 2013 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior consent from the Manager, NSW Parliamentary Research Service, other than by Members of the New South Wales Parliament in the course of their official duties. Inaugural speeches in the NSW Parliament by Gareth Griffith NSW PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY RESEARCH SERVICE Gareth Griffith (BSc (Econ) (Hons), LLB (Hons), PhD), Manager, Politics & Government/Law .......................................... (02) 9230 2356 Lenny Roth (BCom, LLB), Acting Senior Research Officer, Law ............................................ (02) 9230 3085 Lynsey Blayden (BA, LLB (Hons)), Research Officer, Law ................................................................. (02) 9230 3085 Talina Drabsch (BA, LLB (Hons)), Research Officer, Social Issues/Law ........................................... (02) 9230 2484 Jack Finegan (BA (Hons), MSc), Research Officer, Environment/Planning..................................... (02) 9230 2906 Daniel Montoya (BEnvSc (Hons), PhD), Research Officer, Environment/Planning ..................................... (02) 9230 2003 John Wilkinson (MA, PhD), Research Officer, Economics ...................................................... (02) 9230 2006 Should Members or their staff require further information about this publication please contact the author. -

Koala Protection Act Sent to Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull

23 May 2016 Australian Press Release: Koala Protection Act sent to Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull Koala Foundation The Australian Koala Foundation (AKF) has written to Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, Opposition Leader Bill Shorten, Nationals Leader Barnaby Joyce and Greens Leader Richard A.C.N. 010 922 102 Di Natale today to request their support for a Koala Protection Act. The Koala Protection Act is a piece of national legislation that has been formulated by the AKF in consultation with legal teams in Australia and overseas focusing on protecting Koala habitat. Current legislation focuses on the Koala itself but not their habitat. A draft of the Act was enclosed, along with a Statutory Declaration for all leaders to sign prior to the election that states that they will seek to support the Koala via this legislation should they be re-elected. CEO of the AKF Deborah Tabart OAM said that the Act is based on the USA’s Bald Eagle Act that brought the Bald Eagle back from the brink of extinction. She said as Australia’s national icon, the Koala needs the same strength of purpose. “It is not our intention to offend the leaders by requesting they sign a Statutory Declaration, but rather a determination borne of frustration over the AKF’s 30-year experience,” said Ms Tabart. “Since 1988 when I was appointed as CEO of the AKF I have had conversations and correspondence with the who’s who of Australian politics; Environment Ministers at the Federal level and Premiers at the State level."[see notes below] Ms Tabart said the number of Environment Ministers in each State and the Mayors of the 320 Councils in Koala Habitat that she has also corresponded with is too high to remember. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FIFTY-FIFTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION 9 April 2003 (extract from Book 4) Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor JOHN LANDY, AC, MBE The Lieutenant-Governor Lady SOUTHEY, AM The Ministry Premier and Minister for Multicultural Affairs ....................... The Hon. S. P. Bracks, MP Deputy Premier, Minister for Environment, Minister for Water and Minister for Victorian Communities.............................. The Hon. J. W. Thwaites, MP Minister for Finance and Minister for Consumer Affairs............... The Hon. J. Lenders, MLC Minister for Education Services and Minister for Employment and Youth Affairs....................................................... The Hon. J. M. Allan, MP Minister for Transport and Minister for Major Projects................ The Hon. P. Batchelor, MP Minister for Local Government and Minister for Housing.............. The Hon. C. C. Broad, MLC Treasurer, Minister for Innovation and Minister for State and Regional Development......................................... The Hon. J. M. Brumby, MP Minister for Agriculture........................................... The Hon. R. G. Cameron, MP Minister for Planning, Minister for the Arts and Minister for Women’s Affairs................................... The Hon. M. E. Delahunty, MP Minister for Community Services.................................. The Hon. S. M. Garbutt, MP Minister for Police and Emergency Services and -

Country Week: Bringing the City to the Country?

Country Week: Bringing the City to the Country? Phil McManus and John Connell Recent decades have seen seemingly inexorable population decline in many parts of rural and regional Australia, despite local and national strategies to avert emerging economic and population imbalances (Country Shire Councils Association and Country Urban Councils Association Working Party; Pritchard and McManus). Since 2004 a novel initiative has sought to encourage new migration flows into rural Australia. Country Week, a three-day city fair operating in New South Wales and Queensland, involves rural and regional councils and other organisations publicising the advantages of rural areas and small towns and encouraging households to relocate from cities. Unlike most strategies for regional development, which are usually based on stimulating business activity, Country Week is a private sector initiative (albeit supported by governments), and is targeted at particular households. Country Week seeks to revitalise less obviously attractive regional areas as well as meeting and matching employment demands and opportunities in thriving regional areas. In so doing it has stimulated new ways of conceiving the country, challenged some perceptions of an urban-rural divide and created more flexible images of rural life. Initiated by business groups from Armidale, in northern New South Wales, Country Week Expo has been held on four occasions in Sydney, and in Brisbane for the first time in 2007. The locations varyÐRosehill Gardens Racecourse in western Sydney contrasts with the inner-urban South Bank location in Brisbane. Entry is free to the public. The event is supported by significant political figures from across the political divide. Former Labor Premier of NSW, Morris Iemma, opened the 2006 Expo, which also featured a keynote speech by then Liberal Party Senator Amanda Vanstone, while the Expo has prominent National Party support. -

Vol15no4.Pdf

A new award for young writers Eureka Street is delighted to announce the inaugural Margaret Dooley Young Writers' Award One of the di These arguments ideally address peo pl e who own religious be li ef, and those whose view of the world is secu lar. To reflect ethical ly on public issues is a demanding discipline. h•s field. Margaret and Brendan Dooley have longstanding connection s to the Jesuits and Xavier Co llege . Margaret always appreciated the value of commun ication and education for young people, based on spiritual and personal val ues. She graduated from Sacre Coeur College in 1950, com menced nursing at St Vin ce nt's Hospital and, with Brendan, raised four chil dren. Margaret died in 2004. The Dooley family are pleased to support th is initiative. previously published or unpublished, under the age of 40. Entrants must submit two previously unpublished articles that offer: ethical reflection directed to a non-specialist audience on any serious to pic, appeal to humane values, such as those that are found within, but are not exclusive to, the best of the Christian trad ition , clear argument and elegant expression, and a generosity and courtesy of spirit animating forceful argument. One article shou ld be of no more than 800 words. The second shoul d be of no more than 2000 words. They may take up the sa me, or different, topics. Entries are to be submitted by 5pm Friday, 29 July 2005, to : Margaret Dooley Young Writers' Award, Eureka Street, PO Box 553, Richmond VIC 3121. -

From Constitutional Convention to Republic Referendum: a Guide to the Processes, the Issues and the Participants ISSN 1328-7478

Department of the Parliamentary Library INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES •~J..>t~)~.J&~l<~t~& Research Paper No. 25 1998-99 From Constitutional Convention to Republic Referendum: A Guide to the Processes, the Issues and the Participants ISSN 1328-7478 © Copyright Commonwealth ofAustralia 1999 Except to the exteot of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent of the Department ofthe Parliamentary Library, other than by Senators and Members ofthe Australian Parliament in the course oftheir official duties. This paper has been prepared for general distribntion to Senators and Members ofthe Australian Parliament. While great care is taken to ensure that the paper is accurate and balanced,the paper is written using information publicly available at the time of production. The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Information and Research Services (IRS). Advice on legislation or legal policy issues contained in this paper is provided for use in parliamentary debate and for related parliamentary purposes. This paper is not professional legal opinion. Readers are reminded that the paper is not an official parliamentary or Australian govermnent document. IRS staff are available to discuss the paper's contents with Senators and Members and their staffbut not with members ofthe public. , ,. Published by the Department ofthe Parliamentary Library, 1999 INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES , Research Paper No. 25 1998-99 From Constitutional Convention to Republic Referendum: A Guide to the Processes, the Issues and the Participants Professor John Warhurst Consultant, Politics and Public Administration Group , 29 June 1999 Acknowledgments This is to acknowledge the considerable help that I was given in producing this paper. -

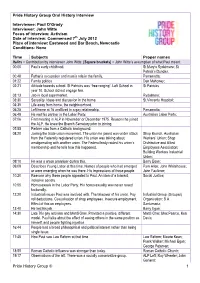

Paul O'grady Interviewer: John Witte Focus O

Pride History Group Oral History Interview Interviewee: Paul O’Grady Interviewer: John Witte Focus of interview: Activism Date of interview: Commenced 7th July 2012 Place of interview: Eastwood and Bar Beach, Newcastle Conditions: None Time Subjects Proper names Italics = Contribution by interviewer John Witte, [Square brackets] = John Witte’s assumption of what Paul meant. 00:00 Paul’s early childhood. St Mary’s Rydalmere; St Patrick’s Dundas; 00:48 Father’s occupation and mum’s role in the family. Parramatta; 01:22 Family politics. Dan Mahoney; 02:21 Attitude towards school. St Patricks was “free ranging”. Left School in St Patricks year 10. School did not engage him. 03:13 Job in local supermarket. Rydalmere; 03:30 Sexuality. Ideas and discussion in the home. St Vincents Hospital; 04:35 Life away from home, the neighbourhood. 05:25 Left home at 16 and lived in a gay relationship. Parramatta; 06:49 He met his partner in the Labor Party. Australian Labor Party; 07:06 First meeting in ALP in November or December 1975. Reasons he joined the ALP. He knew the Branch Secretary prior to joining. 07:55 Partner also from a Catholic background. 08:20 Joining the trade union movement. The union he joined was under attack Shop Branch, Australian from the Federally registered union. His union was talking about Workers’ Union; Shop amalgamating with another union. The Federal body raided his union’s Distributive and Allied membership and he tells how this happened. Employees Association; Building Workers Industrial Union; 09:10 He was a union organiser during this. -

Neville Wran. Australian Biographical Monographs No. 5, by David Clune

158 Neville Wran. Australian Biographical Monographs No. 5, by David Clune. Cleveland (Qld): Connor Court Publishing, 2020. pp. 80, Paperback RRP $19.95 ISBN: 9781922449092 Elaine Thompson Former Associate Professor, University of New South Wales. It’s been many years since I’ve thought about Neville Wran, so I came to this monograph with an oPen mind, limited by two Personal judgements. The first was the belief that Wran was a giant of his time, a real leader and moderniser. The second was the tragedy (farce) of his last years. It was a reminder to us all that there are no guarantees that a great life will be rewarded with a kind death: for Neville Wran that was certainly not the case. Luckily, now with time we remember his leadershiP, his modernising Policies and his largely successful ability to dominate an extraordinarily Powerful Political Party with its deeP factions. David Clune’s monograph, through the use of first-hand materials and comments from Wran’s colleagues, takes us through Wran’s rise to Power, his successes as Premier and his fall via the web of corruPtion and scandal that ended his Premiership. Clune’s narrative is clear and remarkably free of value-judgements. It reminds us just how moribund the Politics and Parliament of NSW were at the time leading uP to Wran’s Government and of all the talent Wran brought with him, which transformed NSW Politics, Policy and Parliament. Of course, there were failures; things left incomPlete and the embedded corruPt culture of NSW Politics largely ignored. Nonetheless, in this monograph we gain a Picture of an extraordinary man leading Australia (via NSW) into the modern era. -

Public Leadership—Perspectives and Practices

Public Leadership Perspectives and Practices Public Leadership Perspectives and Practices Edited by Paul ‘t Hart and John Uhr Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/public_leadership _citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Public leadership pespectives and practices [electronic resource] / editors, Paul ‘t Hart, John Uhr. ISBN: 9781921536304 (pbk.) 9781921536311 (pdf) Series: ANZSOG series Subjects: Leadership Political leadership Civic leaders. Community leadership Other Authors/Contributors: Hart, Paul ‘t. Uhr, John, 1951- Dewey Number: 303.34 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by John Butcher Images comprising the cover graphic used by permission of: Victorian Department of Planning and Community Development Australian Associated Press Australian Broadcasting Corporation Scoop Media Group (www.scoop.co.nz) Cover graphic based on M. C. Escher’s Hand with Reflecting Sphere, 1935 (Lithograph). Printed by University Printing Services, ANU Funding for this monograph series has been provided by the Australia and New Zealand School of Government Research Program. This edition © 2008 ANU E Press John Wanna, Series Editor Professor John Wanna is the Sir John Bunting Chair of Public Administration at the Research School of Social Sciences at The Australian National University. He is the director of research for the Australian and New Zealand School of Government (ANZSOG). -

NSW Legislative Council Hansard Full Day Transcript Page 1 of 3

NSW Legislative Council Hansard Full Day Transcript Page 1 of 3 NSW Legislative Council Hansard Full Day Transcript Extract from NSW Legislative Council Hansard and Papers Tuesday, 21 September 2004. The Hon. ERIC ROOZENDAAL [5.02 p.m.] (Inaugural Speech): I support the Motor Accidents Legislation Amendment Bill. Madam President and honourable members, I am named after my grandfather, a man I never knew. He perished in Auschwitz in 1944. As he was herded into a train, he threw his signet ring to a local railway worker, who later gave it to my grandmother. I proudly wear that ring today. And I hope my grandfather is watching with pride as his grandson joins the oldest Parliament in Australia—a privilege to rival my previous job as head of the oldest branch of the oldest social democratic party in the world. It is therefore with great pride that I deliver my inaugural speech. I am filling the vacancy created by the departure of Tony Burke, who will shortly be elected as a member of the Latham Labor government. I have no doubt Tony will achieve greatness in our national Parliament. I am grateful for his assistance and advice during my transition into the Legislative Council. My presence in this place owes everything to the two great causes to which I have devoted my life: my family and the Labor Party. My beautiful wife, Amanda, and my three wonderful children, Liam, Harry and Jema, are my world. Amanda is a wonderful wife and mother, and, as my partner in life, my rock of support, for which I am eternally grateful. -

Labor's Conflict: Big Business, Workers and the Politics of Class

P1: SJT Trim: 228mm × 152mm Top: 12.653mm Gutter: 21.089mm CUAU095-FM cuau095/Bramble ISBN: 978 0 521 13804 8 September 17, 2010 11:9 LABOR’S CONFLICT Big business, workers and the politics of class Once widely regarded as the workers greatest hope for a better world, the ALP today would rather project itself as a responsible manager of Australian capitalism. Labor’s Conflict provides an insightful account of the transforma- tions in the Party’s policies, performance and structures since its formation. Seasoned political analysts Tom Bramble and Rick Kuhn offer an inci- sive appraisal of the Party’s successes and failures, betrayals and electoral triumphs in terms of its competing ties with bosses and workers. The early chapters outline diverse approaches to understanding the nature of the Party and then assess the ALP’s evolution in response to major social upheavals and events, from the strikes of the 1890s, through two World Wars, the Great Depression, and the post-war boom. The records of the Whitlam, Hawke, Keating, Rudd and Gillard governments are then dissected in detail. The compelling conclusion offers alternatives to the Australian Labor Party, for those interested in progressive change. Tom Bramble is Senior Lecturer in Industrial Relations in the School of Business at the University of Queensland. Rick Kuhn is Reader in Political Science in the School of Politics and Inter- national Relations at the Australian National University. i P1: SJT Trim: 228mm × 152mm Top: 12.653mm Gutter: 21.089mm CUAU095-FM cuau095/Bramble ISBN: 978