View Local and Traditional Knowledge in the Hay River Watershed ______

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OTC October Newsletter Final Draft

The Office of the Treaty Commissioner (OTC) is mandated to advance the Treaty goal of establishing good relations among all people of Saskatchewan. The Office of the Treaty Commissioner continues to work with First Nation’s, provincial school systems, and other educational institutions to raise the awareness and understanding of Treaties and First Nations People Quarterly Newsletter Also available on our website at Volume 1 Issue 3 www.otc.ca October 2014 Annual Livelihood – Livelihood – OTC OTC All Nations Woodland Challenges in Saskatchewan First Education Speakers Traditional st Nations Economic Family & Youth Cree Gathering the 21 Century Development Bureau Network Gathering By: George E. Lafond By: Milton Tootoosis By: April Roberts By: Brenda Ahenekew By: Jennifer Heimbecker By: Robin Bendig This year’s theme for There is an urgency Participants also The community of “The people of The “Gathering” the Woodland Cree to defining what learned about Stanley Mission Saskatoon, you focused on Gathering was, “pimâcihisowin” ‘branding’ and hosts a spectacular walked with us when preserving and “Strengthening means as we move communicating their three day event the load was heavy, strengthening First Unity, Celebrating forward in the new communities; called the River and for that we will Nations culture, Culture, Promoting age business planning; Gathering. The always cherish you,” traditions and Community and and financial literacy Gathering is held identity by offering Recognizing next to the oldest various ceremonies History.” Church in and workshops. Saskatchewan 3-4 5 6 7 8 9 DID YOU KNOW? Reconciliation with our sister The OTC welcomes Rhett Sangster as Director of province - OTC commends the Reconciliation and Community Partnerships. -

Key Terms and Concepts for Exploring Nîhiyaw Tâpisinowin the Cree Worldview

Key Terms and Concepts for Exploring Nîhiyaw Tâpisinowin the Cree Worldview by Art Napoleon A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Faculty of Humanities, Department of Linguistics and Faculty of Education, Indigenous Education Art Napoleon, 2014 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Key Terms and Concepts for Exploring Nîhiyaw Tâpisinowin the Cree Worldview by Art Napoleon Supervisory Committee Dr. Leslie Saxon, Department of Linguistics Supervisor Dr. Peter Jacob, Department of Linguistics Departmental Member iii ABstract Supervisory Committee Dr. Leslie Saxon, Department of Linguistics Supervisor Dr. Peter Jacob, Department of Linguistics Departmental MemBer Through a review of literature and a qualitative inquiry of Cree language practitioners and knowledge keepers, this study explores traditional concepts related to Cree worldview specifically through the lens of nîhiyawîwin, the Cree language. Avoiding standard dictionary approaches to translations, it provides inside views and perspectives to provide broader translations of key terms related to Cree values and principles, Cree philosophy, Cree cosmology, Cree spirituality, and Cree ceremonialism. It argues the importance of providing connotative, denotative, implied meanings and etymology of key terms to broaden the understanding of nîhiyaw tâpisinowin and the need -

Understanding Aboriginal and Treaty Rights in the Northwest Territories: Chapter 2: Early Treaty-Making in the NWT

Understanding Aboriginal and Treaty Rights in the Northwest Territories: Chapter 2: Early Treaty-making in the NWT he first chapter in this series, Understanding Aboriginal The Royal Proclamation Tand Treaty Rights in the NWT: An Introduction, touched After Great Britain defeated France for control of North briefly on Aboriginal and treaty rights in the NWT. This America, the British understood the importance of chapter looks at the first contact between Aboriginal maintaining peace and good relations with Aboriginal peoples and Europeans. The events relating to this initial peoples. That meant setting out rules about land use contact ultimately shaped early treaty-making in the NWT. and Aboriginal rights. The Royal Proclamation of 1763 Early Contact is the most important statement of British policy towards Aboriginal peoples in North America. The Royal When European explorers set foot in North America Proclamation called for friendly relations with Aboriginal they claimed the land for the European colonial powers peoples and noted that “great frauds and abuses” had they represented. This amounted to European countries occurred in land dealings. The Royal Proclamation also asserting sovereignty over North America. But, in practice, said that only the Crown could legally buy Aboriginal their power was built up over time by settlement, trade, land and any sale had to be made at a “public meeting or warfare, and diplomacy. Diplomacy in these days included assembly of the said Indians to be held for that purpose.” entering into treaties with the indigenous Aboriginal peoples of what would become Canada. Some of the early treaty documents aimed for “peace and friendship” and refer to Aboriginal peoples as “allies” rather than “subjects”, which suggests that these treaties could be interpreted as nation-to-nation agreements. -

Interview Summary

Interview Summary Interviewee: Ronnie Semansha Date: November 4, 2009 Location: Chateh Administration Office Interviewers: Kathrin Janssen, Adena Dinn “This [BC] is our traditional lands” -Ronnie Semansha Hunting and Trapping Ronnie hunts for moose in British Columbia (BC) near Kotcho Lake along the winter access road that spans from Rainbow Lake to Fort Nelson. He once shot a moose adjacent to Cabin Lake. He also uses the Sierra Yoyo Desan road and the winter access road that loops around Kotcho Lake for hunting. He takes this route once a week beginning on Friday afternoons when he is finished work. Ronnie also hunts in the area near Kwokullie Lake; he travels there via the winter access on the 31st baseline. Ronnie strictly hunts for moose in BC, and noted that there are hardly any caribou left. He explained that there used to be lots of caribou in BC but there has been a drop in recent times. Fishing Ronnie noted that there are pickerel in Kotcho Lake and explained that there are all different kinds of fish out there [BC]. Travel Routes Ronnie travels to BC using the winter access roads. He noted that there were two roads that he generally used, one from Rainbow Lake to Fort Nelson and one that cuts North to the Zama area (along the 31st baseline). When he does go out, other community members will often accompany him and everyone chips in a little for gas and supplies. However, he generally goes out for just one day and does not require supplies beyond fuel. Transcript 13 If he cannot travel to a certain area via the winter roads then Ronnie will often use a skidoo and the cutlines to access those areas. -

Prepared For: Prepared By

NOVA Gas Transmission Ltd. Overview of the Hydrostatic Test Program Northwest Mainline Expansion August 2012 APPENDIX C WILDLIFE REVIEW Page C-1 WILDLIFE REVIEW FOR THE NOVA GAS TRANSMISSION LTD. NORTHWEST MAINLINE EXPANSION HYDROSTATIC TEST WATER SOURCES, ACCESS AND BORROW PITS August 2012 7212 Prepared for: Prepared by: NOVA Gas Transmission Ltd. A Wholly Owned Subsidiary of TERA Environmental Consultants TransCanada PipeLines Limited Suite 1100, 815 - 8th Avenue S.W. Calgary, Alberta T2P 3P2 Calgary, Alberta Ph: 403-265-2885 NOVA Gas Transmission Ltd. Wildlife Review Northwest Mainline Expansion August 2012 / 7212 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................. 1 2.0 METHODS ....................................................................................................................................... 2 2.1 Field Data Collection ........................................................................................................... 2 2.2 Traditional Ecological Knowledge ....................................................................................... 2 3.0 RESULTS - KYKLO CREEK SECTION ........................................................................................... 3 3.1 Borrow Pit Sites ................................................................................................................... 3 3.2 Hydrostatic Test Site and Access ...................................................................................... -

Indigenous Languages

INDIGENOUS LANGUAGES PRE-TEACH/PRE-ACTIVITY Have students look at the Indigenous languages and/or language groups that are displayed on the map. Discuss where this data came from (the 2016 census) and what biases or problems this data may have, such as the fear of self-identifying based on historical reasons or current gaps in data. Take some time to look at how censuses are performed, who participates in them, and what they can learn from the data that is and is not collected. Refer to the online and poster map of Indigenous Languages in Canada featured in the 2017 November/December issue of Canadian Geographic, and explore how students feel about the number of speakers each language has and what the current data means for the people who speak each language. Additionally, look at the language families listed and the names of each language used by the federal government in collecting this data. Discuss with students why these may not be the correct names and how they can help in the reconciliation process by using the correct language names. LEARNING OUTCOMES: • Students will learn about the number and • Students will learn about the importance of diversity of languages and language groups language and the ties it has to culture. spoken by Indigenous Peoples in Canada. • Students will become engaged in learning a • Students will learn that Indigenous Peoples local Indigenous language. in Canada speak many languages and that some languages are endangered. INDIGENOUS LANGUAGES Foundational knowledge and perspectives FIRST NATIONS “One of the first acts of colonization and settlement “Our languages are central to our ceremonies, our rela- is to name the newly ‘discovered’ land in the lan- tionships to our lands, the animals, to each other, our guage of the colonizers or the ‘discoverers.’ This is understandings, of our worlds, including the natural done despite the fact that there are already names world, our stories and our laws.” for these places that were given by the original in- habitants. -

Ridington-Dane-Zaa Digital Archive Repatriation Project

Contract Position Description December 10, 2020 Position Title Archival Assistant – Ridington-Dane-zaa Digital Archive Repatriation Project Project Background The Ridington-Dane-zaa Digital Archive (RDA) project is a collaborative digital repatriation initiative between: • The Ridington family ethnographers and their Dane-zaa heritage collection(s)i, • The Dane-zaa (Dene peoples indigenous to the Peace River region) communities whose culture is documented by the Ridington Collection: o Blueberry River First Nation o Doig River First Nation o Halfway River First Nation o Prophet River First Nation • University & industry partners including: o UBC CEDaR Lab as interim platform/portal host and steward o BC Hydro as community archive capacity development funder o Nation Governance Initiative, grant issued to Doig River First Nation by New Relationship Trust to help define Athabaskan / Dane-zaa specific protocols for stewardship including access, use, attribution and sharing (2020-2021) https://www.newrelationshiptrust.ca/funding/nation-governance/ o (potentially) UNBC as interim archival storage for physical master materials. Place for final storage to be determined. Options being explored at this time include: § Tse Kwą̂ Heritage Centre at Charlie Lake, BC § Dene Heritage Centre (in proposal/development stage for Indigenous communities of the Peace River Region) Goal The goal of this project is to digitally archive and catalog the entire Ridington collection so that it can be returned (repatriated) to communities for their use and stewardship. Ridington-Dane-zaa Collection History The Ridington Collection of Dane-zaa audio recordings, images, video recordings, and texts began in 1964 after Robin Ridington and Antonia Mills (Antonia Ridington at the time) had met at Harvard University in 1963 as students, married, and began their field work with the Dane-zaa. -

Local Alberta Treaties, Metis Nation of Alberta Regions, Metis Settlements, and Indigenous Nations Acknowledgements

Local Alberta Treaties, Metis Nation of Alberta Regions, Metis Settlements, and Indigenous Nations Acknowledgements Prepared for the Alberta Council of Women’s Shelters and their members by Lewis Cardinal, March 2018 Contents ACWS Acknowledgments 4 Traditional Land Acknowledgments 4 On Reserve Member Recognition 4 Why we do Treaty Acknowledgments 5 Local Alberta Treaties, Metis Nation of Alberta Regions, Metis Settlements, and Indigenous Nations Acknowledgements 6 Banff 6 Bow Valley Emergency Shelter 6 Brooks 6 Cantera Safe House 6 Calgary 6 Kerby Rotary Shelter 6 YWCA Sheriff King Home 6 The Brenda Strafford Centre for the Prevention of Domestic Violence 7 Discovery House 7 Sonshine Centre 7 Calgary Women’s Emergency Shelter 7 Camrose 8 Camrose Women’s Shelter 8 Cold Lake 8 Dr. Margaret Savage Crisis Centre 8 Joie’s Phoenix House 8 Edmonton 8 SAGE Senior’s Safe House 8 WIN House 9 Lurana Shelter 9 La Salle 9 Wings of Providence 10 Enilda 10 Next Step 10 Sucker Creek Emergency Women’s Shelter 10 Fairview 10 Crossroads Resource Centre 10 Wood Buffalo Region 11 Wood Buffalo Second Stage Housing 11 Unity House 11 Grande Cache 11 Grande Cache Transition House 11 Grande Prairie 11 Odyssey House 11 Serenity Place 12 High Level 12 Safe Home 12 High River 12 2 | Page Rowan House Emergency Shelter 12 Hinton 12 Yellowhead Emergency Shelter 12 Lac La Biche 13 Hope Haven Emergency Shelter 13 Lynne’s House 13 Lethbridge 13 YWCA Harbour House 13 Lloydminster 13 Dolmar House 13 Lloydminster Interval Home 14 Maskwacis 14 Ermineskin Women’s Shelter 14 Medicine Hat 14 Musasa House 14 Phoenix Safe House 14 Morley 14 Eagle’s Nest Stoney Family Shelter 14 Peace River 15 Peace River Regional Women’s Shelter 15 Pincher Creek 15 Pincher Creek Women’s Emergency Shelter 15 Red Deer 15 Central Alberta Women’s Emergency Shelter 15 Rocky Mountain House 15 Mountain Rose Women’s Shelter 15 Sherwood Park 16 A Safe House 16 Slave Lake 16 Northern Haven Women’s Shelter 16 St. -

LANGUAGES of the LAND a RESOURCE MANUAL for ABORIGINAL LANGUAGE ACTIVISTS

LANGUAGES of THE LAND A RESOURCE MANUAL FOR ABORIGINAL LANGUAGE ACTIVISTS Prepared by: Crosscurrent Associates, Hay River Prepared for: NWT Literacy Council, Yellowknife TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory Remarks - NWT Literacy Council . 2 Definitions . 3 Using the Manual . 4 Statements by Aboriginal Language Activists . 5 Things You Need to Know . 9 The Importance of Language . 9 Language Shift. 10 Community Mobilization . 11 Language Assessment. 11 The Status of Aboriginal Languages in the NWT. 13 Chipewyan . 14 Cree . 15 Dogrib . 16 Gwich'in. 17 Inuvialuktun . 18 South Slavey . 19 North Slavey . 20 Aboriginal Language Rights . 21 Taking Action . 23 An Overview of Aboriginal Language Strategies . 23 A Four-Step Approach to Language Retention . 28 Forming a Core Group . 29 Strategic Planning. 30 Setting Realistic Language Goals . 30 Strategic Approaches . 31 Strategic Planning Steps and Questions. 34 Building Community Support and Alliances . 36 Overcoming Common Language Myths . 37 Managing and Coordinating Language Activities . 40 Aboriginal Language Resources . 41 Funding . 41 Language Resources / Agencies . 43 Bibliography . 48 NWT Literacy Council Languages of the Land 1 LANGUAGES of THE LAND A RESOURCE MANUAL FOR ABORIGINAL LANGUAGE ACTIVISTS We gratefully acknowledge the financial assistance received from the Government of the Northwest Territories, Department of Education, Culture and Employment Copyright: NWT Literacy Council, Yellowknife, 1999 Although this manual is copyrighted by the NWT Literacy Council, non-profit organizations have permission to use it for language retention and revitalization purposes. Office of the Languages Commissioner of the Northwest Territories Cover Photo: Ingrid Kritch, Gwich’in Social and Cultural Institute INTRODUCTORY REMARKS - NWT LITERACY COUNCIL The NWT Literacy Council is a territorial-wide organization that supports and promotes literacy in all official languages of the NWT. -

Jtc1/Sc2/Wg2 N3427 L2/08-132

JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3427 L2/08-132 2008-04-08 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation Международная организация по стандартизации Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Proposal to encode 39 Unified Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics in the UCS Source: Michael Everson and Chris Harvey Status: Individual Contribution Action: For consideration by JTC1/SC2/WG2 and UTC Date: 2008-04-08 1. Summary. This document requests 39 additional characters to be added to the UCS and contains the proposal summary form. 1. Syllabics hyphen (U+1400). Many Aboriginal Canadian languages use the character U+1428 CANADIAN SYLLABICS FINAL SHORT HORIZONTAL STROKE, which looks like the Latin script hyphen. Algonquian languages like western dialects of Cree, Oji-Cree, western and northern dialects of Ojibway employ this character to represent /tʃ/, /c/, or /j/, as in Plains Cree ᐊᓄᐦᐨ /anohc/ ‘today’. In Athabaskan languages, like Chipewyan, the sound is /d/ or an alveolar onset, as in Sayisi Dene ᐨᕦᐣᐨᕤ /t’ąt’ú/ ‘how’. To avoid ambiguity between this character and a line-breaking hyphen, a SYLLABICS HYPHEN was developed which resembles an equals sign. Depending on the typeface, the width of the syllabics hyphen can range from a short ᐀ to a much longer ᐀. This hyphen is line-breaking punctuation, and should not be confused with the Blackfoot syllable internal-w final proposed for U+167F. See Figures 1 and 2. 2. DHW- additions for Woods Cree (U+1677..U+167D). ᙷᙸᙹᙺᙻᙼᙽ/ðwē/ /ðwi/ /ðwī/ /ðwo/ /ðwō/ /ðwa/ /ðwā/. The basic syllable structure in Cree is (C)(w)V(C)(C). -

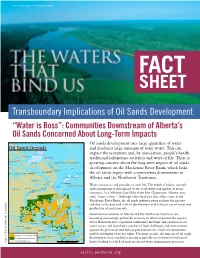

Transboundary Implications of Oil Sands Development “Water Is Boss”: Communities Downstream of Alberta’S Oil Sands Concerned About Long-Term Impacts

Photo: David Dodge, The Pembina Institute FACT SHEET Transboundary Implications of Oil Sands Development “Water is Boss”: Communities Downstream of Alberta’s Oil Sands Concerned About Long-Term Impacts Yellowknife (! Lutselk'e (! Oil sands development uses large quantities of water Oil Sands Deposit and produces large amounts of toxic waste. This can Great Slave Lake impact the ecosystem and, by association, people’s health, Fort Providence (! Fort Resolution (! traditional subsistence activities and ways of life. There is ie River ackenz M Hay River S la Northwest Territories (! v growing concern about the long-term impact of oil sands e R iv e r development on the Mackenzie River Basin, which links Fort Smith (! Fond-du-Lac (! the oil sands region with communities downstream in Lake Athabasca Alberta and the Northwest Territories. er Alberta iv R ce Fort Chipewyan a (! Pe Saskatchewan Water sustains us and provides us with life. The health of plants, animals Lake Claire High Level Fox Lake Rainbow Lake (! (! and communities is determined by the availability and quality of water (! Fort Vermilion (! La Crête (! resources. As a Mikisew Cree Elder from Fort Chipewyan, Alberta, once said, “water is boss.” Although other land uses also affect water in the Mackenzie River Basin, the oil sands industry poses perhaps the greatest risk due to the pace and scale of development and its heavy use of water and Manning Fort McMurray La Loche (! ! (! r ( e production of contaminants. iv R a c s a Buffalo Narrows Peace River b (! a Downstream residents in Alberta and the Northwest Territories are (! h Wabasca t Fairview (! A (! becoming increasingly politically active in an effort to protect the region’s High Prairie water. -

The Cultural Ecology of the Chipewyan / by Donald Stewart Mackay.

ThE CULTURAL ECOLOGY OF TkE CBIPE%YAN UONALD STEhAkT MACKAY b.A., University of british Columbia, 1965 A ThESIS SUBMITTED IN PAhTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE HEObIRCMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the department of Sociology and Anthropology @ EONALD STECART MACKAY, 1978 SIMON F hAShR UNlVERSITY January 1978 All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in, part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name : Donald Stewart Mackay Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: The Cultural Ecology of the Chipewyan Examining Cormnit tee : Chairman : H. Sharp Senior Supervisor- - N. Dyck C.B. Crampton . Fisher Departme'nt of Biological Sciences / ,y/y 1 :, Date Approved: //!,, 1 U The of -- Cultural Ecology .- --------the Chipewyan ----- .- ---A <*PI-: (sign-ir ~re) - Donald Stewart Mackay --- (na~t) March 14, 1978. (date ) AESTRACT This study is concerned with the persistence of human life on the edge of the Canadian Barren Grounds. The Chipewyan make up the largest distinct linguistic and cultural group and are the most easterly among the Northern Athapaskan Indians, or Dene. Over many centuries, the Chipewyan have maintained a form of social life as an edge-of-the-forest people and people of the Barren Grounds to the west of Hudson Bay. The particular aim of this thesis is to attempt, through a survey of the ecological and historical 1iterature , to elucidate something of the traditional adaptive pattern of the Chipewyan in their explcitation of the subarc tic envirorient . Given the fragmentary nature of much of the historical evidence, our limited understanding of the subarctic environment, and the fact that the Chipewyan oecumene (way of looking at life) is largely denied to the modern observer, we acknowledge that this exercise in ecological and historical reconstruction is governed by serious hazards and limitations.