Anime: a Critical Introduction, by Rayna Denison

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japanese Film and Television Aaron Gerow

Yale University From the SelectedWorks of Aaron Gerow 2011 Japanese Film and Television Aaron Gerow Available at: https://works.bepress.com/aarongerow/42/ I J Routledge Handbook of Japanese Culture _andSociety "Few books offer such a broad and kaleidoscopic view of the complex and contested society that is contemporary Japan. Students and professionals alike may use this as a stand-alone reference text, or as an invitation to explore the increasingly diverse range of Japan-related titles offered by Routledge." Joy Hendry, Professor of Social Anthropology and Director of the Europe Japan Research Centre at Oxford Brookes University, UK Edited by Victoria Lyon Bestor and "This is the first reference work you should pick up if you want an introduction to contemporary Japanese society and culture. Eminent specialists skillfully pinpoint key developments Theodore C. Bestor, and explain the complex issues that have faced Japan and the Japanese since the end of World with Akiko Yamagata War II." Elise K. Tipton, Honorary Associate Professor of Japanese Studies in the School of Languages and Cultures at the University of Sydney, Australia I I~~?ia~:!!~~:up LONDON AND NEW YORK William H. Coaldrake I , I Further reading ,I Buntrock, Dana 2001 Japanese Architectureas a CollaborativeProcess: Opportunities in a Flexible Construction Culture. London: Spon Press. Coaldmke, William H. 1986-87 Manufactured Housing: the New Japanese Vernacular. Japan Architect 352-54, 357. ' 17 The Japan Foundation, and Architectural Institute of Japan 1997 ContemporaryJapanese Architecture, 1985-96. Tokyo: The Japan Foundation. JSCA 2003 Nihon kenchiku koz6 gijutsu kyokai (ed.), Nihon no kozo gijutsu o kaeta kenchikuhyakusen, Tokyo: Japanese film and television Shokokusha. -

Western Literature in Japanese Film (1910-1938) Alex Pinar

ADVERTIMENT. Lʼaccés als continguts dʼaquesta tesi doctoral i la seva utilització ha de respectar els drets de la persona autora. Pot ser utilitzada per a consulta o estudi personal, així com en activitats o materials dʼinvestigació i docència en els termes establerts a lʼart. 32 del Text Refós de la Llei de Propietat Intel·lectual (RDL 1/1996). Per altres utilitzacions es requereix lʼautorització prèvia i expressa de la persona autora. En qualsevol cas, en la utilització dels seus continguts caldrà indicar de forma clara el nom i cognoms de la persona autora i el títol de la tesi doctoral. No sʼautoritza la seva reproducció o altres formes dʼexplotació efectuades amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva comunicació pública des dʼun lloc aliè al servei TDX. Tampoc sʼautoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant als continguts de la tesi com als seus resums i índexs. ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis doctoral y su utilización debe respetar los derechos de la persona autora. Puede ser utilizada para consulta o estudio personal, así como en actividades o materiales de investigación y docencia en los términos establecidos en el art. 32 del Texto Refundido de la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual (RDL 1/1996). Para otros usos se requiere la autorización previa y expresa de la persona autora. En cualquier caso, en la utilización de sus contenidos se deberá indicar de forma clara el nombre y apellidos de la persona autora y el título de la tesis doctoral. -

Kunigami Diss Final2

OF CLOUDS AND BODIES: FILM AND THE DISLOCATION OF VISION IN BRAZILIAN AND JAPANESE INTERWAR AVANT-GARDES A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by André Keiji Kunigami August, 2018 © 2018 André Keiji Kunigami OF CLOUDS AND BODIES: FILM AND THE DISLOCATION OF VISION IN BRAZILIAN AND JAPANESE INTERWAR AVANT-GARDES André Keiji Kunigami, Ph. D. Cornell University 2018 Of Clouds and Bodies: Film and the Dislocation of Vision in Brazilian and Japanese Interwar Avant-gardes examines the political impact of film in conceptualizations of the body, vision, and movement in the 1920s and 1930s avant-gardes of Brazil and Japan. Through photographs, films, and different textual genres—travel diary, screenplay, theoretical essay, movie criticism, novel—I investigate the similar political role played by film in these “non-Western” avant-gardes in their relation to the idea of modernity, usually equivalent to that of the “West.” I explore racial, political, and historical entanglements that emerge when debates on aesthetic form encounters the filmic medium, theorized and experienced by the so-called “non-Western” spectator. Through avant-garde films such as Mário Peixoto’s Limite (1930), and Kinugasa Teinosuke’s A Page of Madness (1926); the theorizations of Octávio de Faria and Tanizaki Jun’ichirō; and the photographs and writings by Mário de Andrade and Murayama Tomoyoshi, this dissertation follows the clash between the desire for a universal and disembodied vision, and the encounter with filmic perception. I argue that the filmic apparatus, as a technology and a commodity, emphasizes an embodied and localized experience of vision and time that revealed the discourse on cultural-historical iii difference—the distinction between West and Rest, or modern and non-modern—as a suppressive modulator of material power dynamics embedded in racial, class, and gender hierarchies enjoyed by the cosmopolitan elite in the “peripheral” spaces. -

Japanese Art Cinema: an Sample Study

Japanese Art Cinema: An Sample Study Date/Location of Sample Study: 21st June 2012, The Hostry, Norwich Cathedral, Third Thursday Lecture Series, Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Cultures Dr Rayna Denison with Dr Woojeong Joo What is Japanese cinema? Who does it belong to – the people of Japan, or a global audience? Outside of Japan, what does Japanese cinema mean to people? The rather muddled understanding of Japanese cinema, as popular cinema or art cinema still matters, because the representational stakes are high: which films travel to where is important because films often become enmeshed in wider discussions about ‘ideology’ and ‘culture.’ In academia, publishers and scholars have tended to focus on films that are internationally available, which therefore means that only certain films get ‘speak’ the Japanese nation, while others remain invisible to international audiences. Given that our earliest international understandings of ‘Japanese cinema’ came through film festivals and were consequently driven by notions of ‘art cinema,’ it is worth exploring an audience’s understandings of internationally distributed Japanese cinema today against this ‘traditional’ sense of an international Japanese film culture. By focusing on Japanese ‘art cinema’ for this study, we want to unpack a little of what this term means beyond academia (particularly given how infrequently academics engage with this category overtly); to seek out some of the meanings of contemporary Japanese cinema by asking people what they think counts within the category of ‘Japanese art cinema.’ We want to revisit the slippery category of ‘art cinema’ through an exploratory qualitative analysis of a UK sample audience’s responses to a simple question: How would you define ‘Japanese art cinema’? To help clarify the definitions provided, the sample group was also asked to provide exemplar film texts. -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

Yoshioka, Shiro. "Princess Mononoke: a Game Changer." Princess Mononoke: Understanding Studio Ghibli’S Monster Princess

Yoshioka, Shiro. "Princess Mononoke: A Game Changer." Princess Mononoke: Understanding Studio Ghibli’s Monster Princess. By Rayna Denison. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017. 25–40. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 25 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501329753.ch-001>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 25 September 2021, 01:01 UTC. Copyright © Rayna Denison 2018. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 25 Chapter 1 P RINCESS MONONOKE : A GAME CHANGER Shiro Yoshioka If we were to do an overview of the life and works of Hayao Miyazaki, there would be several decisive moments where his agenda for fi lmmaking changed signifi cantly, along with how his fi lms and himself have been treated by the general public and critics in Japan. Among these, Mononokehime ( Princess Mononoke , 1997) and the period leading up to it from the early 1990s, as I argue in this chapter, had a great impact on the rest of Miyazaki’s career. In the fi rst section of this chapter, I discuss how Miyazaki grew sceptical about the style of his fi lmmaking as a result of cataclysmic changes in the political and social situation both in and outside Japan; in essence, he questioned his production of entertainment fi lms featuring adventures with (pseudo- )European settings, and began to look for something more ‘substantial’. Th e result was a grave and complex story about civilization set in medieval Japan, which was based on aca- demic discourses on Japanese history, culture and identity. -

Modern Girls and New Women in Japanese Cinema

ISSN: 1500-0713 ______________________________________________________________ Article Title: Modern Girls and New Women in Japanese Cinema Author(s): Maureen Turim Source: Japanese Studies Review, Vol. XI (2007), pp. 129-141 Stable URL: https://asian.fiu.edu/projects-and-grants/japan- studies-review/journal-archive/volume-xi-2007/turim.pdf MODERN GIRLS AND NEW WOMEN IN JAPANESE CINEMA Maureen Turim University of Florida The ideal traditional woman and the new modern woman vie for viewer sympathy in Japanese film history, even through the sixties. The song of the “pure Japanese woman” sung by Richiko at the family gathering in Gishiki [Ceremonies] by Oshima Nagisa (1968) raises questions about the “pure” Japanese woman, the ideal traditional role. Hanako, the free yet violent spirit of late fifties womanhood who dominates Oshima’s Taiyō no Hakaba [Burial of the Sun] (1960) raises the question of how the moga, the modern girl, filters across the decades to remain an issue of contestation in the late fifties and sixties. These portrayals demand contextualizing in Japanese film history, and indeed, the history of Japanese women from the Meiji period to the present. The purpose of this essay is to examine the earliest portrayals in Japanese film of the new modern woman and her ideal traditional counterpart to provide that context. In her essay “The Modern Girl as Militant,” Miriam Silverberg looks at the history of the “Moga” or Modan gaaru, as Japanese popular culture termed the Japanese cultural heroine who emerged around 1924 and captured the public’s imagination in the late twenties. She is seen as a “glittering decadent middle-class consumer” who “flaunts tradition in the urban playgrounds,” although Silverberg aligns her with a more politically engaged militant of the same period. -

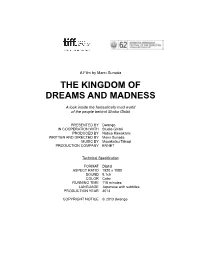

The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness

A Film by Mami Sunada THE KINGDOM OF DREAMS AND MADNESS A look inside the fantastically mad world of the people behind Studio Ghibli PRESENTED BY Dwango IN COOPERATION WITH Studio Ghibli PRODUCED BY Nobuo Kawakami WRITTEN AND DIRECTED BY Mami Sunada MUSIC BY Masakatsu Takagi PRODUCTION COMPANY ENNET Technical Specification FORMAT Digital ASPECT RATIO 1920 x 1080 SOUND 5.1ch COLOR Color RUNNING TIME 118 minutes LANGUAGE Japanese with subtitles PRODUCTION YEAR 2013 COPYRIGHT NOTICE © 2013 dwango ABOUT THE FILM There have been numerous documentaries about Studio Ghibli made for television and for DVD features, but no one had ever conceived of making a theatrical documentary feature about the famed animation studio. That is precisely what filmmaker Mami Sunada set out to do in her first film since her acclaimed directorial debut, Death of a Japanese Salesman. With near-unfettered access inside the studio, Sunada follows the key personnel at Ghibli – director Hayao Miyazaki, producer Toshio Suzuki and the elusive “other” director, Isao Takahata – over the course of approximately one year as the studio rushes to complete their two highly anticipated new films, Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises and Takahata’s The Tale of The Princess Kaguya. The result is a rare glimpse into the inner workings of one of the most celebrated animation studios in the world, and a portrait of their dreams, passion and dedication that borders on madness. DIRECTOR: MAMI SUNADA Born in 1978, Mami Sunada studied documentary filmmaking while at Keio University before apprenticing as a director’s assistant under Hirokazu Kore-eda and others. -

![I'm Going to Be Posting Some Excerpts from the Hideki Anno/Yoshiyuki Tomino Interview from the Char' Counterattack Fan Club Book.Forrefer[...]"](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6918/im-going-to-be-posting-some-excerpts-from-the-hideki-anno-yoshiyuki-tomino-interview-from-the-char-counterattack-fan-club-book-forrefer-1776918.webp)

I'm Going to Be Posting Some Excerpts from the Hideki Anno/Yoshiyuki Tomino Interview from the Char' Counterattack Fan Club Book.Forrefer[...]"

Thread by @khodazat: "I'm going to be posting some excerpts from the Hideki Anno/Yoshiyuki Tomino interview from the Char' Counterattack Fan Club Book.Forrefer[...]" I'm going to be posting some excerpts from the Hideki Anno/Yoshiyuki Tomino interview from the Char's Counterattack Fan Club Book. For reference, the book (released in 1993) wasbasically a doujinshi put together by Hideaki Anno. Beyond the Tomino interview... SGUNDAMIc CHAR'S,COUNDBRS vi Pi +h Panis, BMAF ; th A / mill FR HB*QILUES Rees PROUPT ua FS ROS +EtP—BS Awi— AFI GHA wr TF Pill im LTRS cos8 DHS RMS ShyuyIah mAETIX Rw KA @ TPLPGS) eS PAI BHF2 MAHSEALS GHos500S3Ic\' LUDTIA SY LAU PSSEts ‘= nuun MEFS HA ...1t compiles statements on the film by industry members like Toshio Suzuki, Mamoru Oshii, Haruhiko Mikimoto, Masami Yuki and many more. It's rare and expensive (ranges from $200-500 for a copy) so I haven't read any of it beyond the Tomino interview that was posted online. Also the interview is REALLY LONGso I'm only going to post the excerpts that interest me, not the whole thing. Okay, so withall that out of the way, here's the first excerpt. Anno:So, you know,| really love Char’s Counterattack. Tomino: (bewildered) Oh, thank you. Anno:| waspart of the staff, but even though | looked overall the storyboards,thefirst time | saw it | didn’t really getit. It wasn't until | experienced working as a director in the industry that| felt like | understood. Oguro:It turns out a lot of industry people enjoyed Char’s Counterattack. -

Anime: the Cultural Signification of the Otaku Anime

ANIME: THE CULTURAL SIGNIFICATION OF THE OTAKU ANIME: THE CULTURAL SIGNIFICATION OF THE OTAKU By Jeremy Sullivan, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Jeremy Sullivan, September 2005 MASTER OF ARTS (2005) McMASTER UNIVERSITY (English) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Anime: The Cultural Signification of the Otaku AUTHOR: Jeremy Sullivan, B.A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Dr. Lorraine York NUMBER OF PAGES: v, 103 Abstract Technology has allowed nearly instantaneous communication around the globe and this study examines how cultural transmission occurs through the consumption of television and film. Anime, a term used to refer to a genre of animation that is of Japanese origin, has become immensely popular in North America and has come to simultaneously come to signify a commodifled Japanese youth culture. However, the spectrum of Japanese animation is restricted and controversial anime that includes offensive themes, violent, sexual or illicit material are not televised, or publicized except when associated with negative behaviour. The Otaku are labeled as a socially deviant subculture that is individualistic and amoral. Their struggle for autonomy is represented by their production, circulation and consumption of manga and anime, despite the insistence of the dominant Japanese and North American cultural discourses. This study will examine how publicly circulating definitions, media review, historical relations and censorhip have affected the portrayal of otaku subculture in Japan and internationally. in Acknowledgements A special thanks to my thesis supervisor Lorraine York. Without her patience and guidance this project would not have been possible. -

The University of Chicago Sound Images, Acoustic

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO SOUND IMAGES, ACOUSTIC CULTURE, AND TRANSMEDIALITY IN 1920S-1940S CHINESE CINEMA A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DEVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF CINEMA AND MEDIA STUDIES BY LING ZHANG CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JUNE 2017 Table of Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………………………iii Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………………. x Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Chapter One Sound in Transition and Transmission: The Evocation and Mediation of Acoustic Experience in Two Stars in the Milky Way (1931) ...................................................................................................................................................... 20 Chapter Two Metaphoric Sound, Rhythmic Movement, and Transcultural Transmediality: Liu Na’ou and The Man Who Has a Camera (1933) …………………………………………………. 66 Chapter Three When the Left Eye Meets the Right Ear: Cinematic Fantasia and Comic Soundscape in City Scenes (1935) and 1930s Chinese Film Sound… 114 Chapter Four An Operatic and Poetic Atmosphere (kongqi): Sound Aesthetic and Transmediality in Fei Mu’s Xiqu Films and Spring in a Small Town (1948) … 148 Filmography…………………………………………………………………………………………… 217 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………………… 223 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Over the long process of bringing my dissertation project to fruition, I have accumulated a debt of gratitude to many gracious people who have made that journey enjoyable and inspiring through the contribution of their own intellectual vitality. First and foremost, I want to thank my dissertation committee for its unfailing support and encouragement at each stage of my project. Each member of this small group of accomplished scholars and generous mentors—with diverse personalities, academic backgrounds and critical perspectives—has nurtured me with great patience and expertise in her or his own way. I am very fortunate to have James Lastra as my dissertation co-chair.