The Iron Rhine Arbitration Case: on the Right Legal Track?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Iron Rhine (Ijzeren Rijn) Arbitration (Belgium- Netherlands) Award of 2005

springer.com Law : Dispute Resolution, Mediation, Arbitration Mcmahon, Belinda (Ed.) The Iron Rhine (IJzeren Rijn) Arbitration (Belgium- Netherlands) Award of 2005 With an Introduction by Colin Warbrick, Professor of Public International Law at the University of Birmingham, UK and a Foreword by Tjaco T. van den Hout, Secretary-General of the Permanent Court of Arbitration The Iron Rhine Arbitration (or “IJzeren Rijn” as it is known in Dutch) (2005) decided a dispute between the Kingdom of Belgium and the Kingdom of The Netherlands concerning the reactivation of the Iron Rhine railway linking the Port of Antwerp, Belgium, to the Rhine Basin in Germany across certain parts of Dutch territory. The Arbitral T.M.C. Asser Press Tribunal was called upon to interpret nineteenth century treaties, which granted certain rights to Belgium on the territory of The Netherlands, and to consider the entitlement of The 1st Edition., X, 318 p. 1st Netherlands to insist on conditions specified under Dutch law, particularly with respect to edition environmental protection, for reactivation of the railway. This unique bi-lingual edition comprises the official English version of the Award rendered in the Iron Rhine Arbitration, and a French translation. In a perceptive introduction, Colin Warbrick, Professor of Public Printed book International Law at the University of Birmingham, has considered the Award in the context of Hardcover its contribution to international and European Community law issues. As Professor Warbrick remarks, the significance of this case -

DSM Invests in Knowledge and Innovation in the Netherlands

Press Information DSM Engineering Plastics 2 Havelock Road, #04-01 059763 Singapore www.dsmep.com May 22, 2012 DSM invests in knowledge and innovation in the Netherlands Royal DSM, the global Life Sciences and Materials Sciences company, today announced that it is going to invest approximately €100 million in three new R&D facilities in Delft and Sittard-Geleen (both in the Netherlands) over the next two years. The investment confirms DSM’s commitment to the Netherlands, where the Life Sciences and Materials Sciences company was founded over 110 years ago. The investment in Delft concerns a new laboratory for biotechnological research as well as a DSM contribution to the recently formed consortium for the Bioprocess Pilot Facility (BPF) for bio-research. In Sittard-Geleen a new materials sciences research building will be realized on the Chemelot Campus. Since the new R&D units will closely collaborate with knowledge institutes, government bodies and other companies (including SMEs), the investments will have a major impact on the strengthening of the Dutch knowledge-based economy, precisely in the fields that the Dutch government has designated as key top sectors for the future. The laboratories in Delft and Sittard-Geleen are expected to open their doors in 2014. Some 700 researchers will be working there on innovative solutions to major global challenges in fields such as energy & climate and food & health. As such, the investments fit in with the Netherlands’ position as a front-runner in the field of sustainability. Feike Sijbesma, CEO and Chairman of the Managing Board of Royal DSM, says the investments demonstrate a clear commitment to DSM’s innovation efforts: “Innovation is one of the key growth drivers of the new DSM, and we are increasingly seeing the importance of open innovation involving cooperation with customers and various other parties. -

SHARE Cross-Border Conference: Participation and Integration of Refugees

SHARE Cross-Border Conference: Participation and Integration of Refugees Click to download the meeting agenda. On 28th September 2015, ICMC Europe and SHARE partners Stichting Vluchtelingen Werk (The Dutch Council for Refugees, Limburg), the city of Aachen, and the city of Sittard-Geleen, organised a one day meeting on participation and integration of refugees in the Meuse-Rhine Euregion. The conference was held in the city of Aachen, and attended by representatives of relevant actors from three neighbouring countries -- the Netherlands, Germany, and Belgium. Participants presented reception and integration programmes in their respective cities and regions. Background and purpose of the conference The unprecedented increase in refugee arrivals to Europe from Syria, Eritrea, Afghanistan, and Iraq, has left many towns and cities in Europe struggling to find ways to provide urgent protection and services for these new arrivals, especially given the lack of legal routes and resettlement opportunities for thousands of refugees. However, over the last three years, the Meuse-Rhine Euregion has received a significant number of refugees and in doing has shown a long standing commitment of civil society and local authorities to the welcome, reception and integration of new refugee arrivals. Across the region, there has been a burst of welcoming initiatives and citizen involvement in areas such as housing, education, employment and active participation in society, contributing to a positive environment for refugee protection and integration. In the current context of increasing refugee arrivals, now more than ever, there needs to be cross- border collaboration and exchange in the Meuse-Rhine Euregion with NGOS and city and civil society actors, to generate support for refugees and share experiences and practices as to what has worked well and where there are still challenges. -

Bulletin Newsletter from the EABH

bulletin Newsletter from the EABH 1/2011 European Association for Banking and Financial History e.V. Editorial Dear Colleagues, Our world inds itself confronted with the consequences of recent catastrophic events in Japan and the subsequent butterly effects. People’s revolutions have taken place in Tunisia and Egypt, signiicantly sup- ported, above all things, by the social network platform facebook. This revolutionary spark spread over most Arabic countries and lead to the abolishment of tyrannies in some places, but to leaders ighting their own people in others. The Euro inds itself struggling with the discrepancy between the European inancial and political uniication process, but remains one of the world’s most stable currencies. In this very instant, where recent inancial disasters lead to worldwide doubts about a inancial system undermined by a concept of mathematics and predictabilities, the rationality that underlies modern social sciences has obviously failed as ideology. I cannot help but relect on a remark by Nassim Nicholas Taleb in his book “Black Swans”: “Our inability to predict outliers that imply the inability to predict the course of history, given the share of these events in the dynamics of history”. Will 2011 change our perception and approach towards history? Should we go on believing in concepts of historical evidence? Is it actually possible to take advantage of former experi- ences if we cannot use probability as a tool to understand the present and predict the future? The only thing that is certain is – we do not know! In situations of uncertainty, the element of risk arises. And if we really can’t predict anything, our ability to evaluate, classify and ultimately reduce risk becomes more important. -

THE IRON RHINE CASE and the ART of TREATY INTERPRETATION the Application of Nineteenth Century Obligations in the Twenty-First Century

1 THE IRON RHINE CASE AND THE ART OF TREATY INTERPRETATION The Application of Nineteenth Century Obligations in the Twenty-first Century Ineke van Bladel * The Iron Rhine is a railway linking the port of Antwerp to the Rhine basin in Germany across Dutch territory. Belgium acquired the right of transit over Dutch territory in a treaty from 1839 and requested a reactivation of the railway in 1998. As they failed to come to an understanding in negotiations, the Nether- lands and Belgium decided to submit the case to arbitration. The Arbitral Tribunal they set up in 2003 under the auspices of the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague faced the problem of the application of a nineteenth- century treaty in the twenty-first century.1 The way in which the Tribunal dealt with this problem is the subject of this contribution. 1THE IRON RHINE:ITS HISTORY AND ITS LEGAL FATE At the Congress of Vienna of 1815, Great Britain, Prussia, Austria and Russia decided to unite the region known before the Napoleonic era as the Austrian * Legal counsel at the International Law Division of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. The author acted as co-agent in the Iron Rhine case. The opinions in this essay are solely the author’s and do not necessarily represent those of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. 1 Arbitration Regarding the Iron Rhine (“IJzeren Rijn”) Railway (Belgium/Netherlands), Award of 24 May 2005. The Award as well as the Rules of Procedure and the pleadings (Memorial, Counter-Memorial, Reply and Rejoinder) are available at http://www.pca- cpa.org. -

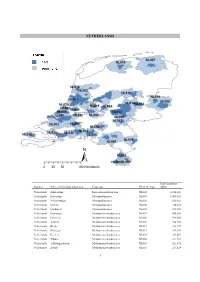

1 Netherlands

NETHERLANDS Total population Country Name of functional urban area Class type ID on the map (2008) Netherlands Amsterdam Large metropolitan area NL002 2,210,410 Netherlands Rotterdam Metropolitan area NL003 1,469,110 Netherlands 's-Gravenhage Metropolitan area NL001 820,021 Netherlands Utrecht Metropolitan area NL004 714,185 Netherlands Eindhoven Metropolitan area NL005 693,033 Netherlands Groningen Medium-sized urban area NL007 458,686 Netherlands Enschede Medium-sized urban area NL008 390,388 Netherlands Arnhem Medium-sized urban area NL009 382,752 Netherlands Breda Medium-sized urban area NL012 333,757 Netherlands Nijmegen Medium-sized urban area NL013 289,165 Netherlands Heerlen Medium-sized urban area NL010 282,697 Netherlands Tilburg Medium-sized urban area NL006 281,151 Netherlands 's-Hertogenbosch Medium-sized urban area NL503 261,478 Netherlands Zwolle Medium-sized urban area NL511 237,524 1 Netherlands Leeuwarden Medium-sized urban area NL015 233,870 Netherlands Apeldoorn Medium-sized urban area NL014 232,141 Netherlands Alkmaar Small urban area NL514 194,441 Netherlands Amersfoort Small urban area NL504 193,576 Netherlands Maastricht Small urban area NL505 186,104 Netherlands Venlo Small urban area NL515 184,715 Netherlands Leiden Small urban area NL507 172,977 Netherlands Sittard-Geleen Small urban area NL016 168,215 Netherlands Dordrecht Small urban area NL506 150,107 Netherlands Haarlem Small urban area NL501 148,373 Netherlands Almelo Small urban area NL519 147,135 Netherlands Roosendaal Small urban area NL020 128,851 Netherlands -

The Relation Between Port Competition and Hinterland Connections

1 THE RELATION BETWEEN PORT COMPETITION AND HINTERLAND CONNECTIONS THE CASE OF THE ‘IRON RHINE’ AND THE ‘BETUWEROUTE’ Hilde Meersman, Tom Pauwels, Eddy Van de Voorde and Thierry Vanelslander Department of Transport and Regional Economics University of Antwerp, Prinsstraat 13, B-2000 Antwerp, Belgium Abstract This paper discusses the relationship between port competition and hinterland connections. The analysis presented is based on expected trends in maritime transport and the likely consequences for seaports. The inauguration of the Betuweroute in 2007 offered the port of Rotterdam additional rail capacity to Germany. The port of Antwerp, meanwhile, is pressing for the reactivation of the Iron Rhine, a direct rail link to that same German hinterland. Research has shown capacity to be the key to success, both in maritime throughput and in hinterland transportation services. Keywords Port competition , hinterland connection, capacity, Iron Rhine, Betuweroute 1. Introduction Within the Hamburg-Le Havre range, the ports of Antwerp and Rotterdam are engaged in a competitive struggle involving two railway lines to the German hinterland. In 2007, the Netherlands inaugurated the so-called Betuweroute, connecting Rotterdam with the Ruhr Area in Germany. Belgium, for its part, intends to reactivate the Iron Rhine, an existing line between Antwerp and the Ruhr. So here we have two transport projects to the same destination zone: a perfect illustration of how port competition can manifest itself on the battlefield of hinterland transportation. In -

Weert, Sittard, Heerlen/Maastricht

richting/direction Weert, Sittard, Heerlen/Maastricht Heerlen EindhovenGeldrop HeezeCentraalMaarheezeWeertRoermondSittard _` _` ` _` _` _` Maastricht _` De informatie op deze vertrekstaat kan zijn gewijzigd. Plan uw reis op ns.nl, in de app of raadpleeg de schermen met actuele vertrekinformatie op dit station. The information on this board may be subject to changes. Check your journey plan on ns.nl or consult the displays with real-time travel information at this station. Vertrektijd/ Treinen rijden op/ Spoor/ Soort trein/ Eindbestemming/ Vertrektijd/ Treinen rijden op/ Spoor/ Soort trein/ Eindbestemming/ Departure Trains run on Platf. Transportation Destination Departure Trains run on Platf. Transportation Destination 16 ma do vr 3 Sprinter Weert via Geldrop 08 ma di wo do vr za zo 1 Intercity Heerlen via Weert-Roermond-Sittard 6 16 di wo 1 Sprinter Weert via Geldrop 17 16 ma di wo do vr za zo 3 Sprinter Weert via Geldrop 29 ma di wo do vr 1 Intercity Maastricht via Weert-Roermond-Sittard 27 ma di wo do vr za zo 1 Intercity Maastricht via Weert-Roermond-Sittard 46 ma di wo do vr 3 Sprinter Weert via Geldrop 38 ma di wo do vr za zo 1 Intercity Heerlen via Weert-Roermond-Sittard 59 ma di wo do vr 1 Intercity Maastricht via Weert-Roermond-Sittard 46 ma di wo do vr za 3 Sprinter Weert via Geldrop 57 ma di wo do vr za zo 1 Intercity Maastricht via Weert-Roermond-Sittard 08 ma di wo do vr 1 Intercity Heerlen via Weert-Roermond-Sittard 7 16 ma di wo do vr za 3 Sprinter Weert via Geldrop 08 ma di wo do vr za zo 1 Intercity Heerlen via Weert-Roermond-Sittard -

Maastricht-Aachen Airport

Arial photo (2003) Maastricht-Aachen Airport 1:20.000 MAASTRICHT-AACHEN AIRPORT 42 MST - MAASTRICHT-AACHEN AIRPORT AIRPORT-ORGANIZATION Name / Address Maastricht Aachen Airport, Vliegveldweg 90, NL-6199 AD Maastricht, Netherlands Website www.maa.nl IATA / ICAO code MST / EHBK Position (LAT/LONG) 50°54´57”N / 005°46´37”E Opening hours 06:00-23:00 hrs (Noise) restrictions Night curfew 23:00-06:00 hrs Ownership NV Luchthaven Maastricht Operator NV Luchthaven Maastricht (civil) users Nederlandse Luchtvaartschool (NLS), European air traffic control center Eurocontrol + General aviation License Article 33 Air traffic law, 28-04-2000* Shareholders** - NV Industriebank LIOF -Provincie Limburg - KVK Limburg-Zuid -Gemeente Maastricht - KvK Aachen (D) -Gemeente Tongeren(B) Comments: *New definite license airfield is planned at the end of 2004. **In 2004 is Holding Businesspark Luchthaven Maastricht (Maastricht Aachen Airport BV and Businesspark MAA BV) sold to a private partner. FINANCE (x €1.000,-, 2003): Company results: 10.677 Company costs: 12.717 -Airport charges 4.028 -Salaries & social costs 8.704 -Rentals & concessions 1.142 -Others (e.g. car parking) 553 Investments: 6.046 REGION Regional profile EURegion Nearest city: Maastricht -Population (x 1.000): 122,2 -Potential market area 1hr by car 2hrs by car 1hr by train 2hrs by train weighted with distance decay (2004, x 1 million pax): 7,3 36,0 3,1 23,5 10,9 Business (airport linked): TechnoPortEurope, Bamford Employment (2003)*: *(Source: Maastricht Aachen Airport, 2004) -Employed direct 171 -

Comparative Cross-Border Study on the Iron Rhine

European Commission Directorate General for Energy and Transport (DG TREN) 1994 TEN-T BUDGET LINE B94/2 Feasibility study Iron Rhine Ministerie van Verkeer en Infrastructuur, Belgium Bundesministerium für Verkehr, Bau-und Wohnungswesen, Germany Ministerie van Verkeer en Waterstaat, the Netherlands Comparative cross-border study on the Iron Rhine Draft Report 14th of May 2001 Colophon Report title: Comparative cross-border study on the Iron Rhine Report characteristic: IJ-Rijn1/WvS/46601 Version: 1.0 With funding of: European Commission Directorate General for Energy and Transport Ministerie van Verkeer en Infrastructuur, Belgium Bundesministerium für Verkehr, Bau-und Wohnungswesen, Germany Ministerie van Verkeer en Waterstaat, the Netherlands Principal: Nationale Maatschappij der Belgische Spoorwegen (SNCB/NMBS) Iron Rhine expert group: ir. D. Demuynck, Nationale Maatschappij der Belgische Spoorwegen ir. P. Van der Haegen, TUC Rail NV ir. J. Peeters, Ministerie van Verkeer en Infrastructuur L. De Ryck, Ministerie van de Vlaamse Gemeenschap ir. K. Heuts, Ministerie van de Vlaamse Gemeenschap ir. G.J.J. Schiphorst, Railinfrabeheer BV drs. D. van Bemmel, Railinfrabeheer BV A. Cardol, Railned BV K. Hohmann, Eisenbahn-Bundesamt ir. dr-ing. A. Hinzen, DB Netz AG Deutsche Bahn Gruppe Drafted by: ARCADIS Berkenweg 7 Postbus 220 3800 AE Amersfoort The Netherlands http://www.arcadis.nl drs.ing.M.B.A.G. Raessen, project manager ir. R.J. van Schie, project manager design ir. R.J. Zijlstra , project manager environment Contents 1 Introduction 11 1.1 -

ANGELET-CV-20-March-2019.Pdf

CURRICULUM VITAE NICOLAS ANGELET I. General information ANGELET, Nicolas Georges Born in Ghent, Belgium, 1 April 1964 Belgian nationality Email: [email protected] [email protected] Tel: +32 477 358 401 II. Education LL.D., Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, 1997 Research at the Max Planck Institute for Foreign Public Law and International Law, Heidelberg, Germany (6 months, 1995-1996) LL.M. in European Law, Université Libre de Bruxelles, 1989 LL.M. in International Law, Université Libre de Bruxelles, 1988 Lic. Jur., University of Ghent, 1986 III. Professional activities : Legal Practice Avocat at the Brussels Bar. Until 31 December 2018, partner and head of the public international law practice with Liedekerke Wolters Waelbroeck Kirkpatrick, Brussels. Associate Tenant, Doughty Street Chambers, United Kingdom. Member of the panel of ICSID conciliators (appointed by Belgium) and arbitrators (appointed by Burundi). Consultancy and litigation in public international law and international business law, notably international investment law, international trade law, public procurement law of international organizations, the law of international organizations, human rights, international humanitarian law, international environmental law, immunities, the law of treaties, the law of state responsibility, the application of international law in the domestic legal order. Litigation in Belgian courts, ICSID arbitration and annulment proceedings, UNCITRAL and ICC arbitral proceedings, arbitration under the aegis of the Permanent Court of Arbitration, International Court of Justice, ICC, European Court of Human Rights, subsidiary organs of the UN Security Council. 1 Cases include the following: Member of the ICSID ad hoc Committee in Víctor Pey Casado and President Allende Foundation v. Chile (ICSID Case No. -

Quickscan Externe Effecten Sittard – Herzogenrath Als Gevolg Van Omrijden Goederentreinen Derde Spoor En Structureel Goederenverkeer

Quickscan externe effecten Sittard – Herzogenrath als gevolg van omrijden goederentreinen Derde Spoor en structureel goederenverkeer Van Eigenaar Rinke Koopman en Rolf Wiemer Kenmerk T20160148-1234481430-13043 Versie 8.0 Datum 27 oktober 2017 Bestand Onderwerp Status Definitief Spoorinfrastructuur Corridors Zuid Quickscan externe effecten 1/26 Inhoudsopgave 1 Inleiding 6 1.1 Context 6 1.2 Opdracht 6 1.3 Doel van de Quickscan 7 1.4 Aanpak 7 1.5 Projectscope 8 2 Uitgangspunten 8 2.1 Algemeen 8 2.1.1 Treinaantallen 9 2.1.2 Vervoer gevaarlijke stoffen 10 2.2 Geluid 10 2.3 Trillingen 11 2.4 Externe veiligheid 11 2.5 Verkeerseffecten 13 3 Onderzoeksresultaten en maatregelen 15 3.1 Geluid op het traject Sittard-Heerlen-Herzogenrath 15 3.1.1 Resultaten 15 3.1.2 Maatregelen 16 3.1.3 Mogelijkheden extra goederenverkeer zonder extra geluidmaatregelen 16 3.2 Trillingen op het traject Sittard-Heerlen-Herzogenrath 17 3.2.1 Resultaten 17 3.3 Externe veiligheid op het traject Sittard-Heerlen-Herzogenrath 18 3.3.1 Resultaten 18 3.3.2 Maatregelen 19 3.4 Vergunbaarheid emplacement Sittard 20 3.4.1 Resultaten 20 3.4.2 Maatregelen 22 3.4.3 Mogelijkheden extra goederenverkeer zonder maatregelen op emplacement Sittard 22 3.5 Overwegbeveiliging 22 3.5.1 Resultaten 22 3.5.2 Maatregelen 23 3.6 Verkeerseffecten 23 3.6.1 Resultaten 23 3.6.2 Maatregelen 24 3.6.3 Mogelijkheden extra goederenverkeer zonder maatregelen voor verkeerseffecten 24 3.7 Effecten van snelheidsverlaging 24 Bijlagen 26 Spoorinfrastructuur Corridors Zuid 2/26 Samenvatting en conclusie Inleiding Het gebruik van het traject ‘ Sittard aansluiting – Herzogenrath’ door goederentreinen kan de komende jaren toenemen door gebruik als omleidingsroute vanwege stremmingen op de Betuweroute en door gebruik als reguliere route voor goederenverkeer.