Newspaper Content in Occupied Lille, Roubaix, and Tourcoing Candice Addie Quinn Marquette University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Capital Implodes and Workers Explode in Flanders, 1789-1914

................................................................. CAPITAL IMPLODES AND WORKERS EXPLODE IN FLANDERS, 1789-1914 Charles Tilly University of Michigan July 1983 . --------- ---- --------------- --- ....................... - ---------- CRSO Working Paper [I296 Copies available through: Center for Research on Social Organization University of Michigan 330 Packard Street Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109 CAPITAL IMPLODES AND WORKERS EXPLODE IN FLANDERS, 1789-1914 Charles Tilly University of Michigan July 1983 Flanders in 1789 In Lille, on 23 July 1789, the Marechaussee of Flanders interrogated Charles Louis Monique. Monique, a threadmaker and native of Tournai, lived in the lodging house kept by M. Paul. Asked what he had done on the night of 21-22 July, Monique replied that he had spent the night in his lodging house and I' . around 4:30 A.M. he got up and left his room to go to work. Going through the rue des Malades . he saw a lot of tumult around the house of Mr. Martel. People were throwing all the furniture and goods out the window." . Asked where he got the eleven gold -louis, the other money, and the elegant walking stick he was carrying when arrested, he claimed to have found them all on the street, among M. Martel's effects. The police didn't believe his claims. They had him tried immediately, and hanged him the same day (A.M. Lille 14336, 18040). According to the account of that tumultuous night authorized by the Magistracy (city council) of Lille on 8 August, anonymous letters had warned that there would be trouble on 22 July. On the 21st, two members of the Magistracy went to see the comte de Boistelle, provincial military commander; they proposed to form a civic militia. -

New Life Old Cities

New Life in Old Cities by Mason Gaffney Robert Schalkenbach Foundation New York Acknowledgments Yisroel Pensack gave lavishly of his time, talent and editorial experience to upgrade and clarify my prose. I am also indebted to Robert Andelson, Clifford Cobb, Richard Biddle, Dick Netzer, Jeffrey Smith, Heather Remoff, Daniel Sullivan, Herbert Barry, William Batt, Nicolaus Tideman, Robert Piper, Robert Fitch, Michael Hudson, Joshua Vincent and Ed O’Donnell for editorial and substantive corrections and additions, most of which I have used. My greatest debt is to Mary M. Cleveland, whose holistic mind and conscientious gentle prodding, reaching across a continent, have guided me to integrate the parts into a coherent whole. I bear sole responsibility for the final product. Mason Gaffney New Life in Old Cities Third Edition Designed by Lindy Davies Paperback ISBN 978-1-952489-01-3 Copyright © 2006, 2014, 2020 Robert Schalkenbach Foundation New York City Tel.: 212-683-6424 www.schalkenbach.org Email: [email protected] CONTENTS Introduction New York City Reborn, 1920-31 Growth Spurts in Some Other Cities L’Envoi Appendices Bibliography About the Author Mason Gaffney recently retired from active teaching at the University of California, Riverside. Prior to Riverside, he was a Professor of Economics at several Universities, a journalist with TIME, Inc., a researcher with Resources for the Future, Inc., the head of the British Columbia Institute for Economic Policy Analysis, which he founded, and an economic consultant to several businesses and government agencies. His most recent book is The Mason Gaffney Reader: Essays on Solving the Unsolvable. He is also the author of After the Crash: Designing a Depression-Free Economy (2009) and, with Fred Harrison, of The Corruption of Economics (1994) as well as numerous scholarly articles. -

Dans Le NORD-PAS DE CALAIS

dans le NORD-PAS DE CALAIS Les associations au cœur de l’opération Une Jonquille pour Curie Le Club Service Soroptimist de Cambrai mettra en vente des produits dérivés jonquille lors du Salon des métiers d'arts le 21 et 22 mars de 10h à 19h. CAMBRAI, salle de la Manutention, rue des Capucins – 59400 Cambrai Le Lycée Professionnel Professeur Clerc d’Outreau organise pendant toute la semaine de nombreuses manifestations dans le cadre d’Une Jonquille pour Curie. MERCREDI 18 MARS Le lycée organise : de 9h00 à 12h00 un cross inter-lycées sur l’axe Liane, l’un des joyaux de la ville de Boulogne-sur-Mer (boulevard d’Alembert et boulevard Diderot) ainsi qu’une vente de jonquilles et d’objets solidaires. BOULOGNE-SUR-MER, Marché du terroir gourmand, Place Dalton - 62200 Boulogne-sur-Mer JEUDI 19 MARS De 9h30 à 17h00, une randonnée à vélo de 80 km entre Dunkerque et Outreau fera découvrir la région ; les kilomètres parcourus permettront de collecter des dons en faveur de l’Institut Curie De 9h00 à 12h00, une vente de jonquilles et d’objets solidaires aura lieu sur le marché d’Outreau. DUNKERQUE, Départ de la randonnée à vélo : Lycée Guy DEBEYRE, rue du Contre-Torpilleur «Triomphant », 59383 Dunkerque OUTREAU, Marché place de l’Hôtel de Ville – 62230 Outreau VENDREDI 20 MARS Le vendredi 20 mars, de 9H à 12H, le lycée sera également présent sur le marché de Le Portel, au cœur de la ville. LE PORTEL, Place de l’Eglise – 62480 Le Portel DIMANCHE 22 MARS Enfin, dimanche 22 mars, un stand de jonquilles et de produits dérivés sera tenu lors des Foulées du printemps à Nesles. -

World War I Concept Learning Outline Objectives

AP European History: Period 4.1 Teacher’s Edition World War I Concept Learning Outline Objectives I. Long-term causes of World War I 4.1.I.A INT-9 A. Rival alliances: Triple Alliance vs. Triple Entente SP-6/17/18 1. 1871: The balance of power of Europe was upset by the decisive Prussian victory in the Franco-Prussian War and the creation of the German Empire. a. Bismarck thereafter feared French revenge and negotiated treaties to isolate France. b. Bismarck also feared Russia, especially after the Congress of Berlin in 1878 when Russia blamed Germany for not gaining territory in the Balkans. 2. In 1879, the Dual Alliance emerged: Germany and Austria a. Bismarck sought to thwart Russian expansion. b. The Dual Alliance was based on German support for Austria in its struggle with Russia over expansion in the Balkans. c. This became a major feature of European diplomacy until the end of World War I. 3. Triple Alliance, 1881: Italy joined Germany and Austria Italy sought support for its imperialistic ambitions in the Mediterranean and Africa. 4. Russian-German Reinsurance Treaty, 1887 a. It promised the neutrality of both Germany and Russia if either country went to war with another country. b. Kaiser Wilhelm II refused to renew the reinsurance treaty after removing Bismarck in 1890. This can be seen as a huge diplomatic blunder; Russia wanted to renew it but now had no assurances it was safe from a German invasion. France courted Russia; the two became allies. Germany, now out of necessity, developed closer ties to Austria. -

2018-0000023

LETTRE CIRCULAIRE n° 2018-0000023 Montreuil, le 03/08/2018 DRCPM OBJET Sous-direction production, Bénéficiaires du versement transport (art. L. 2333-64 et s. du Code gestion des comptes, Général des Collectivités Territoriales) fiabilisation Texte(s) à annoter : VLU-grands comptes et VT LCIRC-2018-0000005 Affaire suivie par : ANGUELOV Nathalie, Changement d'adresse du Syndicat Mixte des Transports Urbains de la BLAYE DUBOIS Nadine, Sambre (9305904) et (93059011). WINTGENS Claire Le Syndicat Mixte des Transports Urbains de la Sambre (9305904) et (9305911) nous informe de son changement d’adresse. Toute correspondance doit désormais lui être envoyée à l’adresse suivante : 4, avenue de la Gare CS 10159 59605 MAUBEUGE CEDEX Les informations relatives au champ d’application, au taux, au recouvrement et au reversement du versement transport sont regroupées dans le tableau ci-joint. 1/1 CHAMP D'APPLICATION DU VERSEMENT TRANSPORT (Art. L. 2333-64 et s. du Code Général des Collectivités Territoriales) SMTUS IDENTIFIANT N° 9305904 CODE DATE COMMUNES CONCERNEES CODE POSTAL TAUX URSSAF INSEE D'EFFET - ASSEVENT 59021 59600, 59604 - AULNOYE-AYMERIES 59033 59620 - BACHANT 59041 59138 - BERLAIMONT 59068 59145 - BOUSSIERES-SUR-SAMBRE 59103 59330 - BOUSSOIS 59104 59168, 59602 - COLLERET 59151 59680 - ECLAIBES 59187 59330 - ELESMES 59190 59600 - FEIGNIES 59225 59606, 59307, 59750, 59607 - FERRIERE-LA-GRANDE 59230 59680 - FERRIERE-LA-PETITE 59231 59680 - HAUTMONT 59291 59618, 59330 1,80 % 01/06/2009 NORD-PAS-DE- CALAIS - JEUMONT 59324 59572, 59573, 59460, -

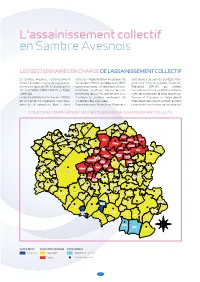

L'assainissement Collectif En Sambre Avesnois

L'assainissement collectif en Sambre Avesnois Les gestionnaires en charge de L’assainissement coLLectif En Sambre Avesnois, l’assainissement partie de l’Agglomération Maubeuge Val sont réunies au sein du Syndicat Inter- collectif est pour une grande majorité des de Sambre (AMVS), qui délègue au SMVS communal d’Assainissement Fourmies- communes (près de 80 %) assuré par le cette compétence. Un règlement d’assai- Wignehies (SIAFW), qui délègue Syndicat Mixte SIDEN-SIAN et sa Régie nissement spécifique s’impose dans les l’assainissement à la société Eau et Force. NOREADE. communes de l’AMVS, permettant ainsi Enfin, les communes de Beaurepaire-sur- SCOTLe Sambre-AvesnoisSyndicat Mixte Val de Sambre (SMVS) d’assurer un meilleur rendement du Sambre et Boulogne sur Helpe gèrent est chargé de la compétence assainisse- traitement des eaux usées. directement leur assainissement en régie Structuresment de compétentes 28 communes, dont et ( 22ou font ) gestionnaires Deux communes, de Fourmies l’assainissement et Wignehies, collectifcommunale, sans passer par un syndicat. structures compétentes et (ou) gestionnaires de L’assainissement coLLectif Houdain- Villers-Sire- lez- Nicole Gussignies Bavay Bettignies Hon- Hergies Gognies- Eth Chaussée Bersillies Vieux-Reng Bettrechies Taisnières- Bellignies sur-Hon Mairieux Bry Jenlain Elesmes Wargnies- La Flamengrie le-Grand Saint-Waast Feignies Jeumont Wargnies- (communeSaint-Waast isolée) Boussois le-Petit Maresches Bavay Assevent Marpent La LonguevilleLa Longueville Maubeuge Villers-Pol Preux-au-Sart (commune -

Sedan Charleville-Mézières

SPECIAL EDITION THE ARDENNES’ ECONOMIC MAGAZINE FRANCE CIAL E P N N S S TAXION ©Amanda Rohde - Zlatko Kostic - Jacob Wackerhausen EXEMPT O E I D I T It’s the moment to invest in the Ardennes ARDENNES : THE GOOD REASONS THE ADVANTAGES - TAX FREE ZONE : HOW-TO-GUIDE AREA CONCERNED - TO WHOM DOES IT APPLY - 200 000€ - THE DIFFERENT EXEMPTIONS ©Michel Tuffery - Charleville-Mézières 2 2008 There has Special edition - a better Ardenne économique économique Ardenne to invest in Jean-Luc Warsmann Deputy for the Ardennes President for the Law Commission at the National Assembly The plan to boost the employment area called « Tax Free Zone » The objective is easy : boost the department’s economic was created by an amendment that I tabled during a cor- fabric either by simplifying the development of existing rective financial tax debate for the year 2006, and which was companies, or by being more competitive than others, voted unanimously at the French National Assembly. encouraging investment projects to be set up in the Ardennes. It allows the reduction of taxes and social security contri- In all countries, companies are demanding a reduction in butions for all investments localized in one of the 362 taxes and social security contributions. Ardennes’ municipalities concerned by this or for all jobs In the 362 Ardennes’ departments this has already been done. created in the same region. Welcome to all project bearers !!!! ©Michel Tuffery - Sedan never been 3 moment the Ardennes Géraud Spire President of the Chamber of Commerce of the Ardennes With this plan to boost the employment market area, French The CCI of the Ardennes is doing all that is possible to and European company directors in the Ardennes, have an guarantee the success of these measures and provide the advantage available which we hope, they will benefit from. -

Routledge Dictionary of Cultural References in Modern French

About the Table of Contents of this eBook. The Table of Contents in this eBook may be off by 1 digit. To correctly navigate chapters, use the bookmark links in the bookmarks panel. The Routledge Dictionary of Cultural References in Modern French The Routledge Dictionary of Cultural References in Modern French reveals the hidden cultural dimension of contemporary French, as used in the press, going beyond the limited and purely lexical approach of traditional bilingual dictionaries. Even foreign learners of French who possess a good level of French often have difficulty in fully understanding French articles, not because of any linguistic shortcomings on their part but because of their inadequate knowledge of the cultural references. This cultural dictionary of French provides the reader with clear and concise expla- nations of the crucial cultural dimension behind the most frequently used words and phrases found in the contemporary French press. This vital background information, gathered here in this innovative and entertaining dictionary, will allow readers to go beyond a superficial understanding of the French press and the French language in general, to see the hidden yet implied cultural significance that is so transparent to the native speaker. Key features: a broad range of cultural references from the historical and literary to the popular and classical, with an in-depth analysis of punning mechanisms. over 3,000 cultural references explained a three-level indicator of frequency over 600 questions to test knowledge before and after reading. The Routledge Dictionary of Cultural References in Modern French is the ideal refer- ence for all undergraduate and postgraduate students of French seeking to enhance their understanding of the French language. -

Directions to FMTC Dunkirk and Port Instructions

Directions to FMTC Dunkirk and port instructions TOTAL (OLEUM) 303 Route du Fortelet 59760 Grande-Synthe France Port access instructions You must register upon arrival at the security (port access / post de gard). You can indicate that you are coming for FMTC / OLEUM. You must hand over your passport or identity card to security. You will receive an access pass and can pass through the entrance gate. When you are through the gate, walk straight on for about 600 meters until you see the OLEUM / FMTC building on your right (see map below). When you leave the site, you can return your access pass to security, after which you will receive your passport or identity card. If you experience problems at the entrance gate, please contact our back office at telephone number +31851307461. Rev. 22-07-2020 1 Route directions Travelling from Dunkirk 1. Take the D601 from Dunkirk towards Grande-Synthe. 2. On the roundabout take the 2nd exit and continue on the D601. 3. Then go right to the Rue du 8 Mai 1945. 4. On the roundabout take the 4th exit to Rue du Comte Jean/D1. 5. Keep following this road and continue on the Route du Fortelet. 6. Take the first exit to the left and your destination (FMTC Dunkirk, TOTAL (OLEUM) is located on your right. Travelling from Calais 1. Take the A16 from Calais towards Grande-Synthe. 2. Keep following this road and eventually take exit 54 towards Dunkerque-Port Est/Grande-Synthe Centre. 3. On the roundabout take the 5th exit to D131. -

Reassessing Marshal Ferdinand Foch

Command in a Coalition War 91 Command in a Coalition War: Reassessing Marshal Ferdinand Foch Elizabeth Greenhalgh* Marshal Ferdinand Foch is remembered, inaccurately, as the unthinking apostle of the offensive, one of the makers of the discredited strategy of the “offensive à outrance” that was responsible for so many French deaths in 1914 and 1915. His acceptance of the German signature on the armistice document presented on behalf of the Entente Allies in 1918 has been overshadowed by postwar conflicts over the peace treaty and then over France’s interwar defense policies. This paper argues that with the archival resources at our disposal it is time to examine what Foch actually did in the years be- tween his prewar professorship at the Ecole Supérieure de Guerre and the postwar disputes at Versailles. I The prewar stereotype of the military leader was influenced by military and diplomat- ic developments on the island of Corsica during the eighteenth century that resulted in the Genoese selling the sovereignty of the island in 1768 to France. This meant that Carlo Buonaparte’s son would be a Frenchman and not Italian, thus altering the face of Europe. The achievements of France’s greatest of “great captains” thus became a benchmark for future French military leaders. A French family from the southwest corner of France near the Pyrenees saw service with Napoleon Bonaparte, and in 1832 one member of that family, named Napoleon Foch for the general, consul and empe- ror, married Mlle Sophie Dupré, the daughter of an Austerlitz veteran. Their second surviving son was named Ferdinand. -

Etude Ornithologique Piémont Vosgien CDEE 14012021 VF

Mise à jour des données ornithologiques du site Natura 2000 du Piémont vosgien 30 novembre 2020 Désignation : Mise à jour des données ornithologiques au sein du site Natura 2000 « Piémont vosgien » Commune(s) : Chaux, Eloie, Etueffont, Giromagny, Grosmagny, Lamadeleine-Val-Des-Anges, Lepuix, Petitmagny, Riervescemont, Rougegoutte, Rougemont-le-Château, Vescemont Département(s) : Territoire de Belfort Région : Bourgogne Franche-Comté Nom du porteur de projet ou organisateur de l'activité / dénomination ou raison sociale, forme juridique et qualité du demandeur : Département du Territoire de Belfort – Direction de l’environnement – Service paysage, aménagement, développement Contacts : Damien Chanteranne Ingénieur départ. 70-90 Centre National de la Propriété Forestière Délégation de Bourgogne – Franche-Comté 6 rue Proudhon 90 000 Belfort Tél : 03 84 58 09 17 – 06 80 58 27 51 Fax : 03 84 58 98 59 Mail : [email protected] Financement : Département du Territoire de Belfort Réalisation : Bonnet Marjolaine, Déforêt Thomas, CD Eau Environnement : Inventaires, rédaction, analyses statistiques, commentaires. Citation : Bonnet M., Déforêt T., 2020 – Mise à jour des données ornithologiques du site Natura 2000 du Piémont vosgien. Département du Territoire de Belfort, CNPF, CD Eau Environnement. 45 pages + annexes RESUME Dans le cadre du suivi ornithologique du site Natura 2000 du Piémont vosgien, une mise à jour des données ornithologiques a été réalisée au printemps 2020. Les résultats sont comparés avec les données du premier inventaire datant de 2009. Ils permettront aussi d’apporter des informations sur l’évolution du peuplement d’oiseaux au sein du site qui serviront à sa gestion. Ce rapport se concentre principalement sur le peuplement d’oiseaux forestiers communs et sur son évolution en relation avec les tendances observées à plus larges échelles. -

Poland – Germany – History

Poland – Germany – History Issue: 18 /2020 26’02’21 The Polish-French Alliance of 1921 By Prof. dr hab. Stanisław Żerko Concluded in February 1921, Poland’s alliance treaty with France, which was intended to afford the former an additional level of protection against German aggression, was the centerpiece of Poland’s foreign policy during the Interwar Period. However, from Poland’s viewpoint, the alliance had all along been fraught with significant shortcomings. With the passage of time, it lost some of its significance as Paris increasingly disregarded Warsaw’s interests. This trend was epitomized by the Locarno conference of 1925, which marked the beginning of the Franco-German rapprochement. By 1933-1934, Poland began to revise its foreign policy with an eye to turning the alliance into a partnership. This effort turned out to be unsuccessful. It was not until the diplomatic crisis of 1939 that the treaty was strengthened and complemented with an Anglo-Polish alliance, which nevertheless failed to avert the German attack on Poland. Despite both France and Great Britain having declared war against the Reich on September 3, 1939, neither provided their Polish ally with due assistance. However, French support was the main factor for an outcome that was generally favorable to Poland, which was to redraw its border with Germany during the Paris peace conference in 1919. It seems that the terms imposed on the Reich in the Treaty of Versailles were all that Poland could ever have hoped to achieve given the balance of power at the time. One should bear in mind that France made a significant contribution to organizing and arming the Polish Army, especially when the Republic of Poland came under threat from Soviet Russia in the summer of 1920.