Best Practices for the Safe Use of Glutaraldehyde in Health Care

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EH&S COVID-19 Chemical Disinfectant Safety Information

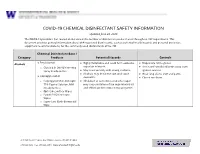

COVID-19 CHEMICAL DISINFECTANT SAFETY INFORMATION Updated June 24, 2020 The COVID-19 pandemic has caused an increase in the number of disinfection products used throughout UW departments. This document provides general information about EPA-registered disinfectants, such as potential health hazards and personal protective equipment recommendations, for the commonly used disinfectants at the UW. Chemical Disinfectant Base / Category Products Potential Hazards Controls ● Ethyl alcohol Highly flammable and could form explosive Disposable nitrile gloves Alcohols ● ● vapor/air mixtures. ● Use in well-ventilated areas away from o Clorox 4 in One Disinfecting Spray Ready-to-Use ● May react violently with strong oxidants. ignition sources ● Alcohols may de-fat the skin and cause ● Wear long sleeve shirt and pants ● Isopropyl alcohol dermatitis. ● Closed toe shoes o Isopropyl Alcohol Antiseptic ● Inhalation of concentrated alcohol vapor 75% Topical Solution, MM may cause irritation of the respiratory tract (Ready to Use) and effects on the central nervous system. o Opti-Cide Surface Wipes o Powell PII Disinfectant Wipes o Super Sani Cloth Germicidal Wipe 201 Hall Health Center, Box 354400, Seattle, WA 98195-4400 206.543.7262 ᅵ fax 206.543.3351ᅵ www.ehs.washington.edu ● Formaldehyde Formaldehyde in gas form is extremely Disposable nitrile gloves for Aldehydes ● ● flammable. It forms explosive mixtures with concentrations 10% or less ● Paraformaldehyde air. ● Medium or heavyweight nitrile, neoprene, ● Glutaraldehyde ● It should only be used in well-ventilated natural rubber, or PVC gloves for ● Ortho-phthalaldehyde (OPA) areas. concentrated solutions ● The chemicals are irritating, toxic to humans ● Protective clothing to minimize skin upon contact or inhalation of high contact concentrations. -

Comparison of Effectiveness Disinfection of 2%

ORIGINAL RESEARCH Journal of Dentomaxillofacial Science (J Dentomaxillofac Sci ) December 2018, Volume 3, Number 3: 169-171 P-ISSN.2503-0817, E-ISSN.2503-0825 Comparison of effectiveness disinfection of 2% Original Research glutaraldehyde and 4.8% chloroxylenol on tooth extraction instruments in the Department of Oral CrossMark http://dx.doi.org/10.15562/jdmfs.v3i2.794 Maxillofacial Surgery, Faculty of Dentistry, University of North Sumatera Month: December Ahyar Riza,* Isnandar, Indra B. Siregar, Bernard Volume No.: 3 Abstract Objective: To compare disinfecting effectiveness of 2% glutaraldehyde while the control group was treated with 4.8% chloroxylenol. Each Issue: 2 and 4.8% chloroxylenol on tooth extraction instruments at the instrument was pre-cleaned using a brush, water and soap for both Department of Oral Surgery, Faculty of Dentistry, University of North groups underwent the disinfection process. Sumatera. Results: The results were statistically analyzed using Mann-Whitney Material and Methods: This was an experimental study with post- Test. The comparison between glutaraldehyde and chloroxylenol First page No.: 147 test only control group design approach. Purposive technique is showed a significant difference to the total bacteria count on applied to collect samples which are lower molar extraction forceps. In instrument after disinfection (p=0.014 < 0.05). this study, sample were divided into 2 groups and each consisting of 18 Conclusion: 2% glutaraldehyde was more effective than 4.8% P-ISSN.2503-0817 instruments. The treatment group was treated with 2% glutaraldehyde chloroxylenol at disinfecting lower molar extraction forceps. Keyword: Disinfection, Glutaraldehyde, Chloroxylenol, Forceps E-ISSN.2503-0825 Cite this Article: Riza A, Siregar IB, Isnandar, Bernard. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2014/0004156A1 Mellstedt Et Al

US 2014.0004156A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2014/0004156A1 Mellstedt et al. (43) Pub. Date: Jan. 2, 2014 (54) BOLOGICAL INHIBITORS OF ROR1 Publication Classification CAPABLE OF INDUCING CELL, DEATH (51) Int. C. (76) Inventors: Hakan Mellstedt, Stockholm (SE): C07K 6/28 (2006.01) Hodjattallah Rabbani, Stockholm (SE); CI2N IS/II3 (2006.01) Ingrid Teige, Lund (SE) (52) U.S. C. CPC ............ C07K 16/28 (2013.01); CI2N 15/1138 (21) Appl. No.: 13/516,925 (2013.01) USPC ...... 424/400; 530/387.9; 536/24.5:536/23.1; (22) PCT Filed: Dec. 10, 2010 435/320.1; 435/325; 435/375; 424/139.1; (86). PCT No.: PCT/EP2010/007524 514/44. A:536/23.53; 435/331 S371 (c)(1), (57) ABSTRACT (2), (4) Date: Mar. 1, 2013 The invention relates to antibodies and siRNA molecules for (30) Foreign Application Priority Data inducing cell death by the specific binding of ROR1, domains thereof of nucleotide molecules encoding ROR1. There are Dec. 18, 2009 (GB) ................................... O922143.3 also provided methods involving and uses of the antibodies Jun. 3, 2010 (GB) ................................... 1OO93O7.8 and siRNA molecules of the invention. Patent Application Publication Jan. 2, 2014 Sheet 1 of 25 US 2014/0004156A1 L/S.*L/SdXL|-WLIXCRIO6] N Patent Application Publication Jan. 2, 2014 Sheet 2 of 25 US 2014/0004156A1 a bi-saw exit-8 ext: xx x: i. s: s x 8. : xxx xx . ex* x8. gri syst {{..} : twic s yxi-xxii. 33. 8 M. : : ised-east x 8. Patent Application Publication Jan. -

Chemical Disinfectants | Disinfection & Sterilization Guidelines | Guidelines Library | Infection Control | CDC 3/19/20, 14:52

Chemical Disinfectants | Disinfection & Sterilization Guidelines | Guidelines Library | Infection Control | CDC 3/19/20, 14:52 Infection Control Chemical Disinfectants Guideline for Disinfection and Sterilization in Healthcare Facilities (2008) Alcohol Overview. In the healthcare setting, “alcohol” refers to two water-soluble chemical compounds—ethyl alcohol and isopropyl alcohol —that have generally underrated germicidal characteristics 482. FDA has not cleared any liquid chemical sterilant or high- level disinfectant with alcohol as the main active ingredient. These alcohols are rapidly bactericidal rather than bacteriostatic against vegetative forms of bacteria; they also are tuberculocidal, fungicidal, and virucidal but do not destroy bacterial spores. Their cidal activity drops sharply when diluted below 50% concentration, and the optimum bactericidal concentration is 60%–90% solutions in water (volume/volume) 483, 484. Mode of Action. The most feasible explanation for the antimicrobial action of alcohol is denaturation of proteins. This mechanism is supported by the observation that absolute ethyl alcohol, a dehydrating agent, is less bactericidal than mixtures of alcohol and water because proteins are denatured more quickly in the presence of water 484, 485. Protein denaturation also is consistent with observations that alcohol destroys the dehydrogenases of Escherichia coli 486, and that ethyl alcohol increases the lag phase of Enterobacter aerogenes 487 and that the lag phase e!ect could be reversed by adding certain amino acids. The bacteriostatic action was believed caused by inhibition of the production of metabolites essential for rapid cell division. Microbicidal Activity. Methyl alcohol (methanol) has the weakest bactericidal action of the alcohols and thus seldom is used in healthcare 488. The bactericidal activity of various concentrations of ethyl alcohol (ethanol) was examined against a variety of microorganisms in exposure periods ranging from 10 seconds to 1 hour 483. -

Guideline for Disinfection and Sterilization in Healthcare Facilities, 2008

Guideline for Disinfection and Sterilization in Healthcare Facilities, 2008 Guideline for Disinfection and Sterilization in Healthcare Facilities, 2008 William A. Rutala, Ph.D., M.P.H.1,2, David J. Weber, M.D., M.P.H.1,2, and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC)3 1Hospital Epidemiology University of North Carolina Health Care System Chapel Hill, NC 27514 2Division of Infectious Diseases University of North Carolina School of Medicine Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7030 1 Guideline for Disinfection and Sterilization in Healthcare Facilities, 2008 3HICPAC Members Robert A. Weinstein, MD (Chair) Cook County Hospital Chicago, IL Jane D. Siegel, MD (Co-Chair) University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Dallas, TX Michele L. Pearson, MD (Executive Secretary) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Atlanta, GA Raymond Y.W. Chinn, MD Sharp Memorial Hospital San Diego, CA Alfred DeMaria, Jr, MD Massachusetts Department of Public Health Jamaica Plain, MA James T. Lee, MD, PhD University of Minnesota Minneapolis, MN William A. Rutala, PhD, MPH University of North Carolina Health Care System Chapel Hill, NC William E. Scheckler, MD University of Wisconsin Madison, WI Beth H. Stover, RN Kosair Children’s Hospital Louisville, KY Marjorie A. Underwood, RN, BSN CIC Mt. Diablo Medical Center Concord, CA This guideline discusses use of products by healthcare personnel in healthcare settings such as hospitals, ambulatory care and home care; the recommendations are not intended for consumer use of the products discussed. 2 -

FACT SHEET Chemical Disinfectants

FACT SHEET Chemical Disinfectants In the laboratory setting, chemical disinfection is the most common method employed to decontaminate surfaces and disinfect waste liquids. In most laboratories, dilutions of household bleach is the preferred method but there are many alternatives that may be considered and could be more appropriate for some agents or situations. There are numerous commercially available products that have been approved by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). EPA Registered Sterilizers, Tuberculocides, and Antimicrobial Products Against Certain Human Public Health Bacteria and Viruses can be found at https://www.epa.gov/pesticide- registration/selected-epa-registered-disinfectants Most EPA-registered disinfectants have a 10-minute label claim. However, OEHS Biosafety recommends a 15-20 minute contact time for disinfection/decontamination. General Considerations Prior to using a chemical disinfectant always consult the manufacturer’s instructions to determine the efficacy of the disinfectant against the biohazards in your lab and be sure to allow for sufficient contact time. In addition, consult the Safety Data Sheet for information regarding hazards, the appropriate protective equipment for handling the disinfectant and disposal of disinfected treated materials. Federal law requires all applicable label instructions on EPA-registered products to be followed (e.g., use-dilution, shelf life, storage, material compatibility, safe use, and disposal). Do not attempt to use a chemical disinfectant for a purpose it was not designed for. • When choosing a disinfectant consider the following: • The microorganisms present • The item to be disinfected or surface(s) • Corrosivity or hazards associated with the chemicals in the disinfectant • Ease of use 1. Organism Sensitivity and Resistant Organisms The innate characteristics of microorganisms often determine its sensitivity to chemical disinfection (Table 1). -

Evaluation of Glutaraldehyde, Chloramine-T, Bronopol, Incimaxx

re Rese tu arc ul h c & a u D Grasteau et al., J Aquac Res Development 2015, 6:12 q e A v f e l o o l p a http://dx.doi.org/10.4172/2155-9546.1000382 m Aquaculture n r e u n o t J ISSN: 2155-9546 Research & Development Research Article Article OpenOpen Access Access Evaluation of Glutaraldehyde, Chloramine-T, Bronopol, Incimaxx Aquatic® and Hydrogen Peroxide as Biocides against Flavobacterium psychrophilum for Sanitization of Rainbow Trout Eyed Eggs Alexandra Grasteau1, Thomas Guiraud1, Patrick Daniel2, Ségolène Calvez3, Valérie Chesneau4 and Michel Le Hénaff1* 1Bordeaux University, CNRS UMR EPOC, Talence, France 2Laboratoire des Pyrénées et des Landes, Mont de Marsan, France 3LUNAM University, Oniris, UMR INRA BioEpAR, Nantes, France 4Groupement de Défense Sanitaire Aquacole d'Aquitaine, Mont de Marsan, France Abstract The effective conditions of glutaraldehyde, chloramine-T, bronopol, Incimaxx Aquatic® and hydrogen peroxide as some biocides commonly used by the aquaculture industry were investigated against F. psychrophilum in sanitization of rainbow trout eyed eggs. Bacteriostatic tests as well as bactericidal tests using ethidium monoazide bromide PCR assays were conducted in vitro on Flavobacterium psychrophilum while impacts of chemical treatments were studied in vivo on 240 [°C × days] rainbow trout eyed eggs. A 20-min contact time with bronopol (up to 2,000 ppm), chloramine-T (up to 1,200 ppm), glutaraldehyde (up to 1,500 ppm), hydrogen peroxide (up to 1,500 ppm) or with Incimaxx Aquatic® (up to 185 ppm, eq. peracetic acid) was effective against F. psychrophilum and did not affect the eyed eggs/fry viability. -

Guideline for Use of High Level Disinfectants & Sterilants For

Guideline for Use of High Level Disinfectants & Sterilants for Reprocessing Flexible Gastrointestinal Endoscopes Guideline for Use of High Level Disinfectants & Sterilants for Reprocessing Flex. Gastrointestinal Endoscopes Acknowledgements Copyright © 2013. Society of Gastroenterology Nurses and Associates, Inc. (SGNA). First published 1998, 2003, 2006, 2007, 2010 & 2013. This document was prepared and written by the SGNA Practice Committee and adopted by the SGNA Board of Directors. It is published as a service to SGNA members. SGNA Practice Committee 2013-14 Michelle R. Juan, MSN, RN, CGRN - Chair Ann Herrin, BSN, RN, CGRN - Co-chair Catherine Concert, DNP, RN, FNP-BC, CGRN Judy Lindsay, MA, BSN, RN, CGRN Midolie Loyola, MSN, RN, CGRN Beja Mlinarich, BSN, RN, CAPA Marilee Schmelzer, PhD, RN Sharon Yorde, BSN, RN, CGRN Kristine Barman, BSN, RN, CGRN Cynthia M. Friis, Med, BSN, RN-BC Reprints are available for purchase from SGNA Headquarters. To order, contact: Department of Membership Services Society of Gastroenterology Nurses and Associates, Inc. 330 North Wabash Chicago, IL 60611-4267 Tel: (800) 245-SGNA or (312) 321-5165 Fax: (312) 673-6694 Online: www.SGNA.org Email: [email protected] Disclaimer The Society of Gastroenterology Nurses and Associates, Inc. (SGNA) presents this guideline for use in developing institutional policies, procedures, and/or protocols. Information contained in this guideline is based on current published data and current practice at the time of publication. The Society of Gastroenterology Nurses and Associates, Inc. assumes no responsibility for the practices or recommendations of any member or other practitioner, or for the policies and practices of any practice setting. Nurses and associates function within the limits of state licensure, state nurse practice act, and/or institutional policy. -

Paul-Ehrlich-Institut Bundesinstitut Für Impfstoffe Und Biomedizinische Arzneimittel Federal Institute for Vaccines and Biomedicines

Paul-Ehrlich-Institut Bundesinstitut für Impfstoffe und biomedizinische Arzneimittel Federal Institute for Vaccines and Biomedicines PAUL-EHRLICH-INSTITUT Paul-Ehrlich-Straße 51-59 D-63225 Langen MUTUAL RECOGNITION PROCEDURE MUMS PRODUCT PUBLICLY AVAILABLE ASSESSMENT REPORT FOR A VETERINARY MEDICINAL PRODUCT CLOSTRIPORC A Clostridium perfringens type A – toxoid vaccine, for pigs (pregnant sows and gilts) 1/14 Clostriporc A DE/V/0262/001/MR IDT Mutual Recognition Procedure Public assessment report ______________________________________________________________________ PRODUCT SUMMARY EU Procedure number DE/V/0262/001/MR Name, strength and Clostriporc A pharmaceutical form Clostridium perfringens type A – toxoid vaccine, for pigs (pregnant sows and gilts) Suspension for injection for subcutaneous use Applicant IDT Biologika GmbH Am Pharmapark 06861 Dessau-Roßlau Germany Active substance(s) One vaccine dose (2 ml) contains: Immunologically active substance Clostridium perfringens type A toxoids: alpha toxoid min. 125 rU*/ ml beta2 toxoid min. 770 rU* /ml * toxoid content in relative units per ml, determined in ELISA against an internal standard Adjuvant Montanide Gel 37.4-51.5 mmol/l titratable acrylate units Excipients Thiomersal 0.2 mg ATC Vetcode QI09AB12 Target species pigs (pregnant sows and gilts) Indication for use For the passive immunisation of piglets by active immunisation of pregnant sows and gilts to reduce clinical signs during the first days of life caused by Clostridium perfringens type A expressing alpha and beta2 toxins. This protection was proven in a challenge test with toxins on sucklers on the first day of life. Serological data show that neutralising antibodies are present up to the 4th week after birth. 2/14 Clostriporc A DE/V/0262/001/MR IDT Mutual Recognition Procedure Public assessment report ______________________________________________________________________ Summary of Product Characteristics 1. -

Glutaraldehyde

Right to Know Hazardous Substance Fact Sheet Common Name: GLUTARALDEHYDE Synonyms: 1,3-Diformylpropane; Glutaral; Cidex®; Procide® CAS Number: 111-30-8 Chemical Name: Pentanedial RTK Substance Number: 0960 Date: January 2000 Revision: April 2010 DOT Number: UN 2810 Description and Use EMERGENCY RESPONDERS >>>> SEE LAST PAGE Glutaraldehyde is a colorless glass-like crystal that is usually Hazard Summary in a 2% to 50% water solution. It is used for cold sterilization of Hazard Rating NJDOH NFPA dental and medical equipment and as a preservative, biocide, HEALTH 2 - hardener, and tanning agent. FLAMMABILITY 0 - REACTIVITY 0 - f ODOR THRESHOLD = 0.04 ppm POISONOUS GASES ARE PRODUCED IN FIRE f Odor thresholds vary greatly. Do not rely on odor alone to DOES NOT BURN determine potentially hazardous exposures. Hazard Rating Key: 0=minimal; 1=slight; 2=moderate; 3=serious; 4=severe Reasons for Citation f Glutaraldehyde can affect you when inhaled and by passing f Glutaraldehyde is on the Right to Know Hazardous through the skin. Substance List because it is cited by ACGIH, DOT and f Contact with the liquid and vapor can severely irritate and NIOSH. burn the skin and eyes. f Inhaling Glutaraldehyde can irritate the nose, throat and lungs causing coughing, wheezing and/or shortness of breath. f Glutaraldehyde can cause headache, nausea and vomiting. f Glutaraldehyde may cause a skin allergy and an asthma- like allergy. SEE GLOSSARY ON PAGE 5. Workplace Exposure Limits FIRST AID NIOSH: The recommended airborne exposure limit (REL) is Eye Contact f Immediately flush with large amounts of water for at least 15 0.2 ppm, which should not be exceeded at any time. -

Disinfection 101

Disinfection 101 Last Modified: May 2008 Author: Glenda Dvorak, DVM, MS, MPH Portions Reviewed By: James Roth, DVM, PhD, DACVM; Sandra Amass, DVM, PhD, DABVP Center for Food Security and Public Health 2160 Veterinary Medicine Ames, IA 50011 515-294-7189 www.cfsph.iastate.edu Disinfection 101 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction......................................................................................................................... 3 Disinfectants Defined............................................................................................................ 3 Disinfectant Labels ............................................................................................................... 4 Label Claims ................................................................................................................................ 4 Other Important Information on a Product Label............................................................................. 5 Considerations and assessment for a disinfection action plan .................................................. 5 Microorganism considerations........................................................................................................ 5 Disinfectant considerations............................................................................................................ 6 Environmental considerations ........................................................................................................ 7 Physical Disinfection .................................................................................................................... -

Lignin-Based Hydrogels: Synthesis and Applications

polymers Review Lignin-Based Hydrogels: Synthesis and Applications Diana Rico-García 1, Leire Ruiz-Rubio 2,3,* , Leyre Pérez-Alvarez 2,3 , Saira L. Hernández-Olmos 1, Guillermo L. Guerrero-Ramírez 1 and José Luis Vilas-Vilela 2,3 1 Chemistry Department, University Center of Exact Sciences and Engineering, University of Guadalajara, 44430 Guadalajara, Mexico; [email protected] (D.R.-G.); [email protected] (S.L.H.-O.); [email protected] (G.L.G.-R.) 2 Macromolecular Chemistry Group (LQM), Physical Chemistry Department, Faculty of Science and Technology, University of the Basque Country, 48940 Leioa, Spain; [email protected] (L.P.-A.); [email protected] (J.L.V.-V.) 3 BCMaterials, Basque Center for Materials, Applications and Nanostructures, UPV/EHU Science Park, 48940 Leioa, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-946017972 Received: 19 November 2019; Accepted: 19 December 2019; Published: 3 January 2020 Abstract: Polymers obtained from biomass are an interesting alternative to petro-based polymers due to their low cost of production, biocompatibility, and biodegradability. This is the case of lignin, which is the second most abundant biopolymer in plants. As a consequence, the exploitation of lignin for the production of new materials with improved properties is currently considered as one of the main challenging issues, especially for the paper industry. Regarding its chemical structure, lignin is a crosslinked polymer that contains many functional hydrophilic and active groups, such as hydroxyls, carbonyls and methoxyls, which provides a great potential to be employed in the synthesis of biodegradable hydrogels, materials that are recognized for their interesting applicability in biomedicine, soil and water treatment, and agriculture, among others.