THE CAVALIER ARMY: Its Organisation and Everyday Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Royalist and Parliamentarian War Effort in Shropshire During the First and Second English Civil Wars, 1642-1648

The Royalist and Parliamentarian War Effort in Shropshire During the First and Second English Civil Wars, 1642-1648 Item Type Thesis or dissertation Authors Worton, Jonathan Citation Worton, J. (2015). The royalist and parliamentarian war effort in Shropshire during the first and second English civil wars, 1642-1648. (Doctoral dissertation). University of Chester, United Kingdom. Publisher University of Chester Download date 24/09/2021 00:57:51 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10034/612966 The Royalist and Parliamentarian War Effort in Shropshire During the First and Second English Civil Wars, 1642-1648 Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of The University of Chester For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Jonathan Worton June 2015 ABSTRACT The Royalist and Parliamentarian War Effort in Shropshire During the First and Second English Civil Wars, 1642-1648 Jonathan Worton Addressing the military organisation of both Royalists and Parliamentarians, the subject of this thesis is an examination of war effort during the mid-seventeenth century English Civil Wars by taking the example of Shropshire. The county was contested during the First Civil War of 1642-6 and also saw armed conflict on a smaller scale during the Second Civil War of 1648. This detailed study provides a comprehensive bipartisan analysis of military endeavour, in terms of organisation and of the engagements fought. Drawing on numerous primary sources, it explores: leadership and administration; recruitment and the armed forces; military finance; supply and logistics; and the nature and conduct of the fighting. -

This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from the King’S Research Portal At

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ The militia of London, 1641-1649 Nagel, Lawson Chase The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 23. Sep. 2021 THE MILITIA OF LONDON, 16Lf].16Lt9 by LAWSON CHASE NAGEL A thesis submitted in the Department of History, King' a Co].].ege, University of Lox4on for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 1982 2 ABSTBAC The Trained Bands and. -

The First and Second Battles of Newbury and the Siege of Donnington

:>> LA A^^. ^4' ^4 ''/' feyi'- • • M'^X. ', ^"'f^ >.7 <>7 '-^ A A '' ^ '' '' ^^'^<^^.gS^$i>^(^*?:5<*%=/^-'<:W:^.'# A (5arttell m«t»eraitg Etbtars 3tl)ara. Netn lark BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF HENRY W. SAGE 1891 The date shows whentiy^^Glume was taken. To renew this *"'"jDli[|^^r" call No. and give to fian. ^^'^^^ home; use rules All Books subject to recall All borrowers must regis- ter in the library to borrow books for home use. All books must be re- turned at end of college year for inspection and repairs. Limited books must be returned within the four week limit and not renewed. Students must return all books before leaving town. Officers should arrange for the return of books -wanted during their absence from town. Volumes of periodicals and of pamphlets are held in the library as much as possible. For special pur- .^ poses they are given out for a limited time. Borrowers should not use their library privileges for the benefit of other persons. Books of special value a^ gift books, when the BV^T wisKes it, are not , nlowed to circulate. Readers are asked to re- port all cases of books ' marked or mutilated. Do not deface books by marks and writlag. Cornell University Library DA 415.M74 1884 First and second battles of Newbu^^ 3 1924 027 971 872 c/-' L(j 1U s^A^ ^yj^" Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. -

Memoirs of a Cavalier by Daniel Defoe</H1>

Memoirs of a Cavalier by Daniel Defoe Memoirs of a Cavalier by Daniel Defoe Produced by Audrey Longhurst, Audrey Longhurst, Leah Moser and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team. MEMOIRS OF A CAVALIER or A Military Journal of the Wars in Germany, and the Wars in England. From the Year 1632 to the Year 1648. By Daniel Defoe Edited with Introduction and Notes by Elizabeth O'Neill 1922 INTRODUCTION. page 1 / 385 Daniel Defoe is, perhaps, best known to us as the author of _Robinson Crusoe_, a book which has been the delight of generations of boys and girls ever since the beginning of the eighteenth century. For it was then that Defoe lived and wrote, being one of the new school of prose writers which grew up at that time and which gave England new forms of literature almost unknown to an earlier age. Defoe was a vigorous pamphleteer, writing first on the Whig side and later for the Tories in the reigns of William III and Anne. He did much to foster the growth of the newspaper, a form of literature which henceforth became popular. He also did much towards the development of the modern novel, though he did not write novels in our sense of the word. His books were more simple than is the modern novel. What he really wrote were long stories told, as is _Robinson Crusoe_, in the first person and with so much detail that it is hard to believe that they are works of imagination and not true stories. "The little art he is truly master of, is of forging a story and imposing it upon the world as truth." So wrote one of his contemporaries. -

Cromwelliana the Journal of the Cromwell Association

Cromwelliana The Journal of The Cromwell Association 1996 CROMWELLIANA 1996 SUMMER SEASON 1996 edited by Peter Gaunt ********** ********** CONTENTS The Cromwell Museum, Grammar School Walk, English Experiments In Infantry Equipment, 1620-1650. Huntingdon. By Keith Roberts. 2 Tel (01480) 425830. 'The Smoke Of War': The Impact Of The Civil War open Tuesday-Friday llam-lpm 2-5pm On Cambridgeshire. By S.L. Sadler. 19 Saturday & Sunday 1 lam-lpm 2-4pm Monday closed The Second Battle Of Newbury: A Reappraisal. By Dr T.J. Halsall. 29 admission free An Additional Aspect To The Interpretation Of Marvell's ********** 'Horatian Ode Upon Cromwell's Return From Ireland', Lines 67-72. By Michele V. Ronnick. 39 Oliver Cromwell's House, 29 St Mary's Street, Cromwell's Protectorate: A Collective Leadership? The Ely. Evidence From Foreign Policy. By Dr T.C. Venning. 42 Tel (01353) 662062. 11 The Protector's Ghost: Political Manipulation Of Oliver open every day 1Oam-6pm Cromwell's Memory In The Final Days Of The Republic. By Mark Speakman. 52 admission charge A Swedish Eighteenth Century Poem In English On ********** Oliver Cromwell. By Bertil Haggman. 63 The Commandery, Cromwellian Britain IX. Newmarket, Suffolk, Or 'When Sidbury, The King Enjoys His Own Again'. By John Sutton. 68 Worcester. Tel (01905) 355071. Select Bibliography Of Publications. By Dr Peter Gaunt. 72 open Monday-Saturday 10am-5pm Book Reviews. Sunday 1.30-5.30pm By Professor Ivan Roots and Dr Peter Gaunt. 79 admission charge The Saga Of Cromwell's Head. By Raymond Tong. 94 The Mind Is The Man. By Raymond Tong. -

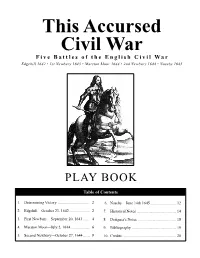

TACW Playbook-3

This Accursed Civil War 1 This Accursed Civil War Five Battles of the English Civil War Edgehill 1642 • 1st Newbury 1643 • Marston Moor 1644 • 2nd Newbury 1644 • Naseby 1645 PLAY BOOK Table of Contents 1. Determining Victory ................................. 2 6. Naseby—June 14th 1645 .......................... 12 2. Edgehill—October 23, 1642 ..................... 2 7. Historical Notes ........................................ 14 3. First Newbury—September 20, 1643 ....... 4 8. Designer's Notes ....................................... 18 4. Marston Moor—July 2, 1644.................... 6 9. Bibliography ............................................. 19 5. Second Newbury—October 27, 1644 ....... 8 10. Credits ....................................................... 20 © 2002 GMT Games 2 This Accursed Civil War Determining Victory Parliament. The King had a clear advantage in numbers and quality of horse. The reverse was the case for Parliament. This Royalists earn VPs for Parliament losses and vice versa. Vic- pattern would continue for some time. tory is determined by subtracting the Royalist VP total from the Parliament VP total. The Victory Points (VPs) are calculated Prelude for the following items: Charles I had raised his standard in Nottingham on August 22nd. Victory The King found his support in the North, Wales and Cornwall; Event Points the Parliament in the South and East. The army of Parliament Eliminated Cavalry Unit ............................................. 10 was at Northampton. The King struck out towards Shrewsbury to gain needed support. Essex moved on Worcester, trying to Per Cavalry Casualty Point place his army between the King and London, as the King's on Map at End ............................................................. 2 army grew at Shrewsbury. By the 12th of October the King felt Eliminated Two-Hex Infantry Unit ............................. 10 he was sufficiently strong to move on London and crush the Eliminated One-Hex Heavy Infantry Unit ................. -

ENGLAND Avon and Berkshire Right: Bath Abbey, Avon

XI\ 1:--ITRC)l)UCTJON r.R Ne\\ m.. n Atlas of the l:ngltsh Civil War (London, 1985) is a useful guide to military events 1ncJud1ng .; co~c 1 se statement of Newman's reinterpretation of. the ~a~tle of M~rston Moor. Royai ((>m111iss1on 011 H1stor1cal A101111me11ts, Newark on Trent; 1'he C1v1/ War S1egeworks (London J964) 1s J supt"rh account, g1v1ng a wealth of detail impossible ro reproduce here, and remain~ cssentJ I reaJ1ng for dedicated explorers. De pHe the research Jnd preparation,~ volu!11e of t~i s kind is b_o~~d to conta!n errors and to omit muc:h "'h1 ·h, on ref1ect1on, 1s "'orthy of 1nclus1on. With the poss1b1ltry of a revised edition in mind \Vt' "·ould be \CCV grateful for having errors and omissions pointed our in as much detail as possible' fh~e should be addrc ed co the publishers at 30, Brunswick Road, Gloucester GLl lJJ. ENGLAND Avon and Berkshire Right: Bath Abbey, Avon. Epiphanius Evesham's fine monument to Sir William Waller's first w1fe,janc (d1633}, was desecrated by Royalist troops during the Civil War and the features of Waller and his wife badly damaged. Below: Donn1ngton Casde, Berks. The huge gatehouse stands before the shattered A\TON rema'1ns of the medieval stronghold. To the lefr 1s part of the earthwork fort thrown up by Sir John Boys's Royalist garrison. b 1 r u1ar Avon passed under Royalist control during the Secured 'or Parliament at the o~t rea: ... od, ... •h; Ki1Zg's hands for two years. -

The Rise of the Anti-Clockwise Newel Stair

The Rise of the Anti-clockwise Newel Stair Newark Castle. Gatehouse, c. 1130-40. The wide anticlockwise spiral stair rising to the audience chamber over gatehouse passage. THE CASTLE STUDIES GROUP JOURNAL NO 25: 2011-12 113 The Rise of the Anti-clockwise Newel Stair The Rise of the Anticlockwise Newel Stair Abstract: The traditional castle story dictates that all wind- ing, newel, turnpike or spiral staircases in medi- eval great towers, keep-gatehouses, tower houses and mural wall towers ascended clockwise. This orthodoxy has it that it offered a real functional military advantage to the defender; a persistent theory that those defending the stair from above had the greatest space in which to use their right- handed sword arm. Conversely, attackers mount- ing an upward assault in a clockwise or right- handed stair rotation would not have unfettered use of their weaponry or have good visibility of their intended victim, as their right sword hand would be too close to the central newel. Fig. 1. Diagrammatic view of Trajan’s Column, Rome, Whilst there may be other good reasons for AD 130, viewed from the east. The interior anticlock- clockwise (CW) stairs, the oft-repeated thesis sup- wise (ACW) stair made from solid marble blocks. porting a military determinism for clockwise stairs is here challenged. The paper presents a Origins and Definitions. corpus of more than 85 examples of anticlockwise The spiral, also known as a vice, helix, helical, (ACW) spiral stairs found in medieval castles in winding, turnpike, or circular stair is an ancient England and Wales dating from the 1070s device, and existing anticlockwise (or counter- through to the 1500s. -

Fantastic Riverside Detached House Set in a Quiet Location at the End of a No

FANTASTIC RIVERSIDE DETACHED HOUSE SET IN A QUIET LOCATION AT THE END OF A NO THROUGH ROAD mitford house donnington village, newbury, berkshire,rg14 2ju FANTASTIC RIVERSIDE DETACHED HOUSE SET IN A QUIET LOCATION AT THE END OF A NO THROUGH ROAD mitford house, donnington village, newbury, berkshire, rg14 2ju Reception hall w drawing room w sitting/family room w kitchen/breakfast room w dining room w study w cloakroom w utility room w master bedroom with en-suite bath/shower room w dressing room w guest bedroom with en-suite basin and shower w 3 further bedrooms w bathroom w double garage w off street parking w large garden leading to river Mileage Central Newbury 1 mile, M4 junction 13 - 3 miles, London Paddington via Newbury from 54 minutes. (All mileages and times are approximate) Situation Historic Donnington Village nestles between the old castle and the river Lambourn and is a beautiful and much sought after village situated in a quiet yet convenient position near the market town of Newbury. Mitford House is located in a conservation area on the edge of the village surrounded by open green belt countryside and the river Lambourn. The property is within easy reach of local shops, a local Waitrose and other supermarkets, offices, fitness centres and many well known good and outstanding state and private schools. The Watermill Theatre is just upstream at Bagnor and there are other theatres and two Donnington golf courses within easy reach. There is a main line railway station in Newbury providing a direct service to London Paddington. -

Shaw House Kitchen Garden Newbury West Berkshire

Shaw House Kitchen Garden Newbury West Berkshire Archaeological Watching Brief for West Berkshire Council CA Project: 770485 CA Report: 16662 November 2016 Shaw House Kitchen Garden Newbury West Berkshire Archaeological Watching Brief CA Project: 770485 CA Report: 16662 Document Control Grid Revision Date Author Checked by Status Reasons for Approved revision by A 17/11/16 Chris Ellis Ray Internal General Edit Richard Kennedy review Greatorex This report is confidential to the client. Cotswold Archaeology accepts no responsibility or liability to any third party to whom this report, or any part of it, is made known. Any such party relies upon this report entirely at their own risk. No part of this report may be reproduced by any means without permission. © Cotswold Archaeology © Cotswold Archaeology Shaw House Kitchen Garden, Newbury, West Berkshire: Archaeological Watching Brief CONTENTS SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................... 2 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 3 2. ARCHAEOLOGICAL BACKGROUND ................................................................ 4 3. AIMS AND OBJECTIVES ................................................................................... 5 4. METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................... 5 5. RESULTS (FIGURES 2-3) ................................................................................ -

SUBTITLE = During and After the Civil

During and After the Civil War The middle of the seventeenth century was of course dominated by the Civil War. Central Berkshire lay in a somewhat precarious position between the Parliamentary strongholds of Windsor and London to the East, and the West country which was largely Royalist. Two of the main royalist fortresses close to Mortimer were Donnington Castle near Newbury, and Basing House. It is likely that the inhabitants of Mortimer favoured the Royalist cause, for the Lord of the Manor at this time, the fifth Marquis of Winchester, was a staunch supporter of King Charles. As the hero of the long siege at Basing House, he came to be called `The Great Loyalist'. Another prominent local landowner, John Lucas, whose family had since the Dissolution occupied the land formerly owned by Reading Abbey, was also imprisoned for his Royalist beliefs, but he escaped and fought at the first Battle of Newbury. As a reward for his efforts he was later created Lord Lucas. At the beginning of the war, Reading was under the control of the Parliamentarians, but the town changed hands several times during the next few years: it was occupied by the Royalist army in November 1642, captured by Parliament after a siege in April 1643, re-occupied by the Royalists in June, abandoned by them in May 1644, and finally held for the remainder of the war by Parliament. Although there is no record of Mortimer itself being the site of any incident, the continual movement of armies throughout the county must have had some impact on the village. -

This Work Is Protected by Copyright and Other Intellectual Property Rights

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Keele Research Repository This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights and duplication or sale of all or part is not permitted, except that material may be duplicated by you for research, private study, criticism/review or educational purposes. Electronic or print copies are for your own personal, non- commercial use and shall not be passed to any other individual. No quotation may be published without proper acknowledgement. For any other use, or to quote extensively from the work, permission must be obtained from the copyright holder/s. The representations of Royalists and Royalism in the press, c. 1637-1646 Paul Alastair Michael Jones PhD History January 2012 Keele University Developing from the recent surge of interest in the Royalist cause during the Civil Wars, this thesis explores the question of how Royalists were portrayed in the press between 1637 and 1646. It addresses the question through textual analysis and specifically examines printed material in an effort to investigate the construction of Royalist identity as well as the peculiarities of Royalist discourse. At its most fundamental level, this thesis seeks to address the issue of Royalist identity, and in doing so suggests that it was predicated on an inconsistent and problematic form of English patriotism. According to the argument presented here, Charles I led a cause that was supposed to protect and champion the core institutions and cultural norms upon which the very nature of Englishness rested. Royalism existed to preserve England from what were perceived as the foreign and anti- English agendas of Parliament.