Cromwelliana the Journal of the Cromwell Association

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Mobilizing the Metropolis: Politics, Plots and Propaganda in Civil War London, 1642-1644 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3gh4h08w Author Downs, Jordan Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Mobilizing the Metropolis: Politics, Plots and Propaganda in Civil War London, 1642-1644 A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by Jordan Swan Downs December 2015 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Thomas Cogswell, Chairperson Dr. Jonathan Eacott Dr. Randolph Head Dr. J. Sears McGee Copyright by Jordan Swan Downs 2015 The Dissertation of Jordan Swan Downs is approved: ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ___________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements I wish to express my gratitude to all of the people who have helped me to complete this dissertation. This project was made possible due to generous financial support form the History Department at UC Riverside and the College of Humanities and Social Sciences. Other financial support came from the William Andrew’s Clark Memorial Library, the Huntington Library, the Institute of Historical Research in London, and the Santa Barbara Scholarship Foundation. Original material from this dissertation was published by Cambridge University Press in volume 57 of The Historical Journal as “The Curse of Meroz and the English Civil War” (June, 2014). Many librarians have helped me to navigate archives on both sides of the Atlantic. I am especially grateful to those from London’s livery companies, the London Metropolitan Archives, the Guildhall Library, the National Archives, and the British Library, the Bodleian, the Huntington and the William Andrews Clark Memorial Library. -

POLITICS, SOCIETY and CIVIL WAR in WARWICKSHIRE, 162.0-1660 Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History

Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History POLITICS, SOCIETY AND CIVIL WAR IN WARWICKSHIRE, 162.0-1660 Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History Series editors ANTHONY FLETCHER Professor of History, University of Durham JOHN GUY Reader in British History, University of Bristol and JOHN MORRILL Lecturer in History, University of Cambridge, and Fellow and Tutor of Selwyn College This is a new series of monographs and studies covering many aspects of the history of the British Isles between the late fifteenth century and the early eighteenth century. It will include the work of established scholars and pioneering work by a new generation of scholars. It will include both reviews and revisions of major topics and books which open up new historical terrain or which reveal startling new perspectives on familiar subjects. It is envisaged that all the volumes will set detailed research into broader perspectives and the books are intended for the use of students as well as of their teachers. Titles in the series The Common Peace: Participation and the Criminal Law in Seventeenth-Century England CYNTHIA B. HERRUP Politics, Society and Civil War in Warwickshire, 1620—1660 ANN HUGHES London Crowds in the Reign of Charles II: Propaganda and Politics from the Restoration to the Exclusion Crisis TIM HARRIS Criticism and Compliment: The Politics of Literature in the Reign of Charles I KEVIN SHARPE Central Government and the Localities: Hampshire 1649-1689 ANDREW COLEBY POLITICS, SOCIETY AND CIVIL WAR IN WARWICKSHIRE, i620-1660 ANN HUGHES Lecturer in History, University of Manchester The right of the University of Cambridge to print and sell all manner of books was granted by Henry VIII in 1534. -

Fuller Genealogy

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2008 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/fullergenealogy04full aP\/ C. TKfi NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY ASTOR, LENOX )i SOMK Fri.T.F.R (".EXKA l.( ; I S IS r.i i, XKWTox i-Ti.i.i-.i.; i:i.i/..\iii-. 1 II \i;i.uriM.\i WII.I.IA.M HVSI.or iri.l.KK IKSSK KR.WKI.IN l-ri.l.l'.K GENEALOGY OF SOME DESCENDANTS OF THOMAS FULLER OF WOBURN COMPILED BY WILLIAM HYSLOP FULLER OF PALMER. MASS. TO WHICH IS ADDED SUPPLEMENTS TO VOLUMES I. II, III PREVIOUSLY COMPILED AND PUBLISHED PRINTED FOR THE COMPILER 1919 THE NEW YORK tiljD£n foundations' FULLER GENEALOGIES COMPILED AND FOR SALE BY WILLIAM H. FULLER 23 School Street, Palmer, Mass. VOLUME I. Some Descendants of Edward Fuller of the Mayflower. I volume 8 vo., cloth, 25 illustrations, 306 pp. Now only sold as part of the set of 4 volumes. Price, $20.00 for the Set. postpaid. VOLUME IL Some Descendants of Dr. Samuel Fuller of the Mayflower. 1 volume 8 vo., cloth, 31 illustrations, 263 pp. Price, postpaid, $5.00. VOLUME III. Some Descendants of Captain Matthew Fuller, also of John Fuller of Newton, John Fuller of Lynn, John Fuller of Ipswich, and Robert Fuller of Dorchester and Dedham, with supplements to Volumes I and II. 8 vo., cloth, 14 illustrations, 325 pp. Price $5.00, postpaid. VOLUME IV. /Some Descendants of Thomas Fuller of Woburn, with Supplements to the previous volumes. Price $6.00, postpaid. PREFACE In compiling the "Genealogy of Some Descendants of Thomas Fuller of Woburn," I have been greatly assisted by the work of the late Elizabeth Abercrombie, whose volume is an authority on the genealogy of the descendants of Joseph^ Fuller, No. -

John Darby and the Whig Canon

JOHN DARBY AND THE WHIG CANON I A celebrated series of books by the English commonwealthmen of the seventeenth century was published between 1698 and 1700. The series included major editions of works by John Milton, Algernon Sidney, and James Harrington, and the civil war memoirs of Edmund Ludlow, Denzil Holles, John Berkeley, and Thomas Fairfax. Collectively these texts have become known as the ‘whig canon’.1 Over the following century this set of writings would profoundly shape the development of republican thought on both sides of the Atlantic.2 The texts of the whig canon would be cited approvingly by thinkers as diverse as Bolingbroke and the founding fathers of the American constitution.3 At their original moment of publication, however, the series was designed to bolster opposition to the consolidation of power by the court whigs under William III. By reasserting ‘true whig’ principles against the corruption of the apostates who made their peace with the court, these historic works were made to chime with the political challenges faced by the opposition in the present moment: attacking the maintenance of standing armies by the state, inveighing against priestcraft, and asserting the primacy of the ancient constitution. 1 Caroline Robbins, The eighteenth-century commonwealthman (Cambridge, MA, 1959), p. 32. 2 J. G. A. Pocock, ‘The varieties of whiggism from exclusion to reform: a history of ideology and discourse’, in Virtue, commerce, and history: essays on political thought and history, chiefly in the eighteenth century (Cambridge, 1985), pp. 215-310; Robbins, Commonwealthman; Blair Worden, Roundhead reputations: the English civil wars and the passions of posterity (London, 2001); Alan Craig Houston, Algernon Sidney and the republican heritage in England and America (Princeton, 1991). -

Cropredy Bridge by MISS M

Cropredy Bridge By MISS M. R. TOYNBEE and J. J. LEEMING I IE bridge over the River Chenveff at Cropredy was rebuilt by the Oxford shire County Council in J937. The structure standing at that time was for T the most part comparatively modern, for the bridge, as will be explained later, has been thoroughly altered and reconstructed at least twice (in J780 and 1886) within the last 160 years. The historical associations of the bridge, especiaffy during the Civil War period, have rendered it famous, and an object of pilgrimage, and it seems there fore suitable, on the occasion of its reconstruction, to collect together such details as are known about its origin and history, and to add to them a short account of the Civil War battle of 1644, the historical occurrence for which the site is chiefly famous. The general history of the bridge, and the account of the battle, have been written by Miss Toynbee; the account of the 1937 reconstruction is by Mr. Leeming, who, as engineer on the staff of the Oxfordshire County Council, was in charge of the work. HISTORY OF TIlE BRIDGE' The first record of the existence of a bridge at Cropredy dates, so far as it has been possible to discover, from the year 1312. That there was a bridge in existence before 1312 appears to be pretty certain. Cropredy was a place of some importance in the :\1iddle Ages. It formed part of the possessions of the See of Lincoln, and is entered in Domesday Book as such. 'The Bishop of Lincoln holds Cropelie. -

The Lives of the Chief Justices of England

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com Cui.U.K. &3o 1 THE LIVES OK THE CHIEF JUSTICES ENGLAND. FROM THE NORMAN CONQUEST TILL THE DEATH OF LORD TENTERDEN. By JOHN LOKD CAMPBELL, LL.D. F.E.S.E.: AUTHOR OF 'THE LIVES OF THE LOKD CHANCELLORS OF ENGLANd.' THIRD EDITION. IN FOUR VOLUMES.— Vol. II. LONDON: JOHN MUEKAY, ALBEMAELE STEEET. 1874. The right of Translation is reserved. Uniform with the present Work. LIVES OF THE LOED CHANCELLOBS, AND Keepers op the Great Skal op England, from the Earliest Times till the Reign of George the Fourth. By John Lord Campbell, LL.D. Fourth Edition. 10 vols. Crown 8vo. 6s. ' each. " A work of sterling merit — one of very great labour, of richly diversified interest, and, we arc satisfied, of lasting value and estimation. We doubt If there be half-a-dozen living men who could produce a Biographical Series on such a scale, at all likely to command so much applause from the candid among the iearned as well as from the curious of the laity." — Quarterly Review. &ONdON: PRINTEd BT WILLIAM CLOWES ANd SONS, STAMFORd STREET ANd CHARING CROSS. CONTENTS OF THE SECOND VOLUME. CHAPTER XI.— continued. LIVES OF THE CHIEF JUSTICES FROM THE DISMISSAL OF SIR EDWARD COKE TILL THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH. Sir Nicholas Hyde, Page 1. His Reputation as a Lawyer, 1. His Con duct as Chief Justice of the King's Bench, 2. -

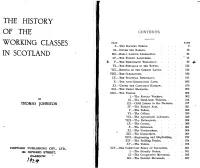

The History of the Working Classes in Scotland

THE HISTORY OF THE CONTENTS. CHAP. WORKING CLASSES I.—THE SLAVERY PERIOD, II.—UNDER THE BARONS, IN SCOTLAND III.—EARLY LABOUR LEGISLATION, IV.—THE FORCED LABOURERS, . $£■ V.—THE DEMOCRATIC THEOCRACY, VI.—THE STRUGGLE IN THE TOWNS, VII.—EEIVING oi" THE COMMON LANDS, VIII.—THE CLEARANCES, IX.—THE POLITICAL DEMOCRACY, X.—THE ANTI-COMBINATION LAWS, XI.—UNDER THE CAPITALIST HARROW, XII.—THE GREAT MASSACRE, XIII.—THE UNIONS, I.—The Factory Workers, BY II.—The Hand-loom Weavers, . THOMAS JOHNSTON III.—Child Labour in the Factories, IV.—The Factory Acts, . V.—The Bakers, VI.-—The Colliers, . VII.—The Agricultural Labourers, VIII.—The Railwaymen, IX.—The Carters, . X.—The Sailormen, XI.—The Woodworkers, XII.—The Ironworkers, XIII.—Engineering and Shipbuilding, XIV.—The Building Trades, XV.—The Tailors, . PORWARD PUBLISHING COY., LTD., XIV.—THE COMMUNIST SEEDS OF SALVATION, I.—The Friendly Orders, 164 HOWARD STREET, II.—The Co-operative Movement, GLASGOW. III.—The Socialist Movement, . tfLf 84 THE HISTORY OF THE WORKING GLASSES. their freedom in the courts, it followed, as a general rule, that the slave was only liberated by death. The result of all these restric CHAPTER V, tions was that coal-mining remained unpopular and the mine-owners in Scotland were still forced to pay higher wages for labour than were THE DEMOCRATIC THEOCRACY. their English confreres. And so the liberating Act of 1799, which " The Solemn League and Covenant finally abolished slavery in the coal mines and saltpans of Scotland, Whiles brings a sigh and whiles a tear; was urged upon Parliament by the more far-seeing coalowners them But Sacred Freedom, too, was there, selves. -

The Morehead Family of North Carolina and Virginia

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from State Library of North Carolina http://www.archive.org/details/moreheadfamilyofOOmore THIS COPY IS NUMBER OF AN EDITION OF FIFTY COPIES PRINTED IN FEBRUARY, NINETEEN HUNDRED AND TWENTY-ONE AND IS PRESENTED TO <f^ tatc £lbraru ,6valclgk,?l . C. THE MOREHEAD FAMILY ; RaleigM 1 1 ;, fHE U ii/ FAMILY GOVERNOR JOHN MOTLEY MOREHEAD , ^VHNMO 1796-1866HEHEAD Portrait by William Garl Broiine, 1S59 IVATfeLY PRINTf NEWYOEF- 1921 ! L ±J G J: ..•i,\\iVn yd Library Worth Carolina State Raleigh THE MOREHEAD FAMILY OF NORTH CAROLINA AND VIRGINIA JOHN MOTLEY MOREHEAD (III) '/ ', PRIVATELY PRINTED NEW YORK 1921 an CopjTight, 1921, by John Motley Morehead (HI) CONTENTS CHAPTER ' PAGE I The Moreheads of England, Scotland and Ireland . 3 II David jNIorehead of London 24 III The Moreheads of the Northern Neck, Virginia . 32 IV The Moreheads of the Northern Piedmont Region 37 V The Moreheads of the South Piedmont Region, Virginia 44 VI The Moreheads of North Carolina 51 VII The Lindsay Family 94 VIII The Harper Family 99 IX The Motley Family 102 X The Forrest Family 106 XI The Ellington Family 107 XII The Norman Family 108 XIII The Gray Family Ill XIV The Connally Family 115 XV The Graves Family 118 XVI The Lathrop Family 124 The Turner Family (See Chapter IV) 37 The Williams Family (See Chapter XIV) . .115 The Lanier Family (See Chapter XIV) .... 115 The Kerr Family (See Chapter XV) 118 r '^' ^ A 7 (.. ?:• 'J- k s ILLUSTRATIONS PAGE Coat of Arms of the Morehead Family .... Facing page lu Governor John Motley Morehead Frontispiece Mrs. -

White Priory Murders

THE WHITE PRIORY MURDERS John Dickson Carr Writing as Carter Dickson CHAPTER ONE Certain Reflections in the Mirror "HUMPH," SAID H. M., "SO YOU'RE MY NEPHEW, HEY?" HE continued to peer morosely over the tops of his glasses, his mouth turned down sourly and his big hands folded over his big stomach. His swivel chair squeaked behind the desk. He sniffed. 'Well, have a cigar, then. And some whisky. - What's so blasted funny, hey? You got a cheek, you have. What're you grinnin' at, curse you?" The nephew of Sir Henry Merrivale had come very close to laughing in Sir Henry Merrivale's face. It was, unfortu- nately, the way nearly everybody treated the great H. M., including all his subordinates at the War Office, and this was a very sore point with him. Mr. James Boynton Bennett could not help knowing it. When you are a young man just arrived from over the water, and you sit for the first time in the office of an eminent uncle who once managed all the sleight-of-hand known as the British Military Intelligence Department, then some little tact is indicated. H. M., although largely ornamental in these slack days, still worked a few wires. There was sport, and often danger, that came out of an unsettled Europe. Bennett's father, who was H. M.'s brother-in-law and enough of a somebody at Washington to know, had given him some extra-family hints before Bennett sailed. "Don't," said the elder Bennett, "don't, under any circumstances, use any ceremony with him. -

The Levellers' Conception of Legitimate Authority

Araucaria. Revista Iberoamericana de Filosofía, Política y Humanidades ISSN: 1575-6823 ISSN: 2340-2199 [email protected] Universidad de Sevilla España The Levellers’ Conception of Legitimate Authority Ostrensky, Eunice The Levellers’ Conception of Legitimate Authority Araucaria. Revista Iberoamericana de Filosofía, Política y Humanidades, vol. 20, no. 39, 2018 Universidad de Sevilla, España Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=28264625008 This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International. PDF generated from XML JATS4R by Redalyc Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative e Levellers’ Conception of Legitimate Authority A Concepção de Autoridade Legítima dos Levellers Eunice Ostrensky [email protected] Universidade de São Paulo, Brasil Abstract: is article examines the Levellers’ doctrine of legitimate authority, by showing how it emerged as a critique of theories of absolute sovereignty. For the Levellers, any arbitrary power is tyrannical, insofar as it reduces human beings to an unnatural condition. Legitimate authority is necessarily founded on the people, who creates the constitutional order and remains the locus of political power. e Levellers also contend that parliamentary representation is not the only mechanism by which the people may acquire a political being; rather the people outside Parliament are the collective agent able to transform and control institutions and policies. In this sense, the Levellers hold that a highly participative community should exert sovereignty, and that decentralized government is a means to achieve that goal. Araucaria. Revista Iberoamericana de Keywords: Limited Sovereignty, Constitution, People, Law, Rights. Filosofía, Política y Humanidades, vol. Resumo: Este artigo analisa como os Levellers desenvolveram uma doutrina da 20, no. -

The 1641 Lords' Subcommittee on Religious Innovation

A “Theological Junto”: the 1641 Lords’ subcommittee on religious innovation Introduction During the spring of 1641, a series of meetings took place at Westminster, between a handful of prominent Puritan ministers and several of their Conformist counterparts. Officially, these men were merely acting as theological advisers to a House of Lords committee: but both the significance, and the missed potential, of their meetings was recognised by contemporary commentators and has been underlined in recent scholarship. Writing in 1655, Thomas Fuller suggested that “the moderation and mutual compliance of these divines might have produced much good if not interrupted.” Their suggestions for reform “might, under God, have been a means, not only to have checked, but choked our civil war in the infancy thereof.”1 A Conformist member of the sub-committee agreed with him. In his biography of John Williams, completed in 1658, but only published in 1693, John Hacket claimed that, during these meetings, “peace came... near to the birth.”2 Peter Heylyn was more critical of the sub-committee, in his biography of William Laud, published in 1671; but even he was quite clear about it importance. He wrote: Some hoped for a great Reformation to be prepared by them, and settled by the grand committee both in doctrine and discipline, and others as much feared (the affections of the men considered) that doctrinal Calvinism being once settled, more alterations would be made in the public liturgy... till it was brought more near the form of Gallic churches, after the platform of Geneva.3 A number of Non-conformists also looked back on the sub-committee as a missed opportunity. -

The Royalist and Parliamentarian War Effort in Shropshire During the First and Second English Civil Wars, 1642-1648

The Royalist and Parliamentarian War Effort in Shropshire During the First and Second English Civil Wars, 1642-1648 Item Type Thesis or dissertation Authors Worton, Jonathan Citation Worton, J. (2015). The royalist and parliamentarian war effort in Shropshire during the first and second English civil wars, 1642-1648. (Doctoral dissertation). University of Chester, United Kingdom. Publisher University of Chester Download date 24/09/2021 00:57:51 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10034/612966 The Royalist and Parliamentarian War Effort in Shropshire During the First and Second English Civil Wars, 1642-1648 Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of The University of Chester For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Jonathan Worton June 2015 ABSTRACT The Royalist and Parliamentarian War Effort in Shropshire During the First and Second English Civil Wars, 1642-1648 Jonathan Worton Addressing the military organisation of both Royalists and Parliamentarians, the subject of this thesis is an examination of war effort during the mid-seventeenth century English Civil Wars by taking the example of Shropshire. The county was contested during the First Civil War of 1642-6 and also saw armed conflict on a smaller scale during the Second Civil War of 1648. This detailed study provides a comprehensive bipartisan analysis of military endeavour, in terms of organisation and of the engagements fought. Drawing on numerous primary sources, it explores: leadership and administration; recruitment and the armed forces; military finance; supply and logistics; and the nature and conduct of the fighting.