Oxford Canal Conservation Area Appraisal PDF 11 MB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tiountfee of Oxford and Berks, Or Some Or One of Them

4373 tiountfee of Oxford and Berks, or some or one of said parishes, townships, and extra-parochial or them, or in the parish of South. Hinksey, in other places, or any of them, which it may be neces- the liberty of the city of Oxford, and the county sary to stop up, alter,, or divert by reason of the of Berks, and terminating at or near the poiat construction of the said intended works. of junction of the London and Birmingham and Midland Railways, at or near Rugby, in the And it is farther intended, by such Act or Acts,, parish of Rugby, in the county of Warwick; to vary or extinguish all existing rights of' privi- which said intended railway or railways, and leges in any manner connected with the lands pro- other works connected therewith, will pass from, posed to be purchased or taken for the purposes in, through, or into, or be situate within the of the said undertaking, or which would in any Several parishes, townships, and extra-parochial manner impede or interfere with the construction, or other places following, or some of them (that is maintenance, or use thereof; and to confer other to say), South Hinksey and North Hinksey, in= the rights and privileges. liberty of the city of Oxford, and in the county of Berks, or one of them; Cumner and Botley, in the And it is also intended, by such Act or Acts, county of Berks; St. Aldate, and the liberty of the either to enable the Great Western Railway Com- Grand Pont, in the city of Oxford, and counties of pany to carry into effect the said intended under- Oxford and Berks, or some or one of them; Saint taking^ or otherwise to incorporate a company, for Ebbes, St. -

09/00768/F Ward: Yarnton, Gosford and Water Eaton Date Valid

Application No: Ward: Yarnton, Date Valid: 18 09/00768/F Gosford and Water August 2009 Eaton Applicant: MHJ Ltd and Couling Holdings Site OS Parcel 9875 Adjoining Oxford Canal and North of The Gables, Address: Woodstock Road, Yarnton Proposal: Proposed 97 berth canal boat basin with facilities building; mooring pontoons; service bollards; fuel; pump out; 2 residential managers moorings; entrance structure with two-path bridge, facilities building with WC’s shower and office; 48 car parking spaces and landscaping. 1. Site Description and Proposal 1.1 The application site is located to the south east of Yarnton and south west of Kidlington. It is situated and accessed to the north of the A44, adjacent to the western side of the Oxford Canal. The access runs through the existing industrial buildings located at The Gables and the site is to the north of these buildings. 1.2 The site has a total area of 2.59 hectares and consists of low lying, relatively flat, agricultural land. There are a number of trees and hedgerows that identify the boundary of the site. 1.3 The site is within the Oxford Green Belt, it is adjacent to a classified road and the public tow path, it is within the flood plain, contains BAP Priority Habitats, is part of a proposed Local Wildlife Site and is within 2km of SSSI’s. 1.4 The application consists of the elements set out above in the ‘proposal’. It is not intended that, other than the manager’s moorings, these moorings be used for residential purposes. The submission is supported by an Environmental Statement, Supporting Statement and a Design and Access Statement. -

Four Thousand Ships Passed Through the Lock: Object-Induced Measure Functions on Events

MANFRED KRIFKA FOUR THOUSAND SHIPS PASSED THROUGH THE LOCK: OBJECT-INDUCED MEASURE FUNCTIONS ON EVENTS 1 . INTRODUCTION 1.1. Event-Related and Object-Related Readings The subject of this paper* is certain peculiar readings of sentences like the following ones: (1)a. Four thousand ships passed through the lock last year. b. The library lent out 23,000 books in 1987. C. Sixty tons of radioactive waste were transported through the lock last year. d. The dry cleaners cleaned 5.7 million bags of clothing in 1987. e. 12,000 persons walked through the turnstile yesterday. Take the first example, (la) (it is inspired by the basic text of the LiLog project of IBM Germany, which first drew my attention to these sen- tences). It clearly has two readings. The first one, call it the object-related reading, says that there are four thousand ships which passed through the lock last year. The second one, call it the event-related reading, says that there were four thousand events of passing through the lock by a ship last year. The object-related reading presupposes the existence of (at least) four thousand ships in the world we are talking about. In the event-related reading, there might be fewer ships in the world. In the limiting case, a single ship passing through the lock about 12 times a day would be suffi- cient. We find the same ambiguity in the other examples of (1). The library might contain fewer than 23,000 books, there might be less than sixty tons of radioactive waste, there might be less than 5.7 million bags of clothing, and there might be fewer than 12,000 persons - but the sentences (lb-e) could still be true in their event-related readings. -

Waterway Dimensions

Generated by waterscape.com Dimension Data The data published in this documentis British Waterways’ estimate of the dimensions of our waterways based upon local knowledge and expertise. Whilst British Waterways anticipates that this data is reasonably accurate, we cannot guarantee its precision. Therefore, this data should only be used as a helpful guide and you should always use your own judgement taking into account local circumstances at any particular time. Aire & Calder Navigation Goole to Leeds Lock tail - Bulholme Lock Length Beam Draught Headroom - 6.3m 2.74m - - 20.67ft 8.99ft - Castleford Lock is limiting due to the curvature of the lock chamber. Goole to Leeds Lock tail - Castleford Lock Length Beam Draught Headroom 61m - - - 200.13ft - - - Heck Road Bridge is now lower than Stubbs Bridge (investigations underway), which was previously limiting. A height of 3.6m at Heck should be seen as maximum at the crown during normal water level. Goole to Leeds Lock tail - Heck Road Bridge Length Beam Draught Headroom - - - 3.71m - - - 12.17ft - 1 - Generated by waterscape.com Leeds Lock tail to River Lock tail - Leeds Lock Length Beam Draught Headroom - 5.5m 2.68m - - 18.04ft 8.79ft - Pleasure craft dimensions showing small lock being limiting unless by prior arrangement to access full lock giving an extra 43m. Leeds Lock tail to River Lock tail - Crown Point Bridge Length Beam Draught Headroom - - - 3.62m - - - 11.88ft Crown Point Bridge at summer levels Wakefield Branch - Broadreach Lock Length Beam Draught Headroom - 5.55m 2.7m - - 18.21ft 8.86ft - Pleasure craft dimensions showing small lock being limiting unless by prior arrangement to access full lock giving an extra 43m. -

Crimond, High Street Cropredy

Crimond, High Street Cropredy Crimond, High Street Cropredy, Oxfordshire, OX17 1NG Approximate distances Banbury 5 miles Junction 11 (M40) 6 miles Oxford 26 miles Stratford upon Avon 21 miles Leamington Spa 17 miles Banbury to London Marylebone by rail approx. 55 mins Banbury to Birmingham by rail approx. 50 mins Banbury to Oxford by rail approx. 17 mins A HANDSOME STONE BUILT HOUSE IN AN ENVIABLE POSITION IN THIS HIGHLY DESIRED VILLAGE. Porch, hall, cloakroom, sitting room, dining room, kitchen/breakfast room, utility room, three double bedrooms, bathroom, detached garage, off road parking, garden. £475,000 FREEHOLD Directions * Large sitting room with two windows to front, From Banbury proceed in a northerly direction ornate feature fireplace (which could be unblocked to toward Southam (A423)>. After approximately 3 be an open fire), slidng double glazed patio doors to miles turn right where signposted to Cropredy. Travel the rear garden. through Great Bourton and follow the road into the village. Follow the road passing the Brasenose pub on * Spacious separate dining room with window to the left and then take the first turning right by The front. Green into High Street and follow the road passing the turn for Church Street and the property will be * Kitchen/breakfast room with base and eye level found after a short distance on the right hand side light oak units, integrated dishwasher, integrated and can be recognised by our "For Sale" board. freezer, fitted electric cooker, free standing fridge, Situation work surfaces and breakfast bar, window to front and CROPREDY is a well served village famous for the glazed door to utility, air conditioning unit. -

The Schuylkill Navigation and the Girard Canal

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 1989 The Schuylkill Navigation and the Girard Canal Stuart William Wells University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Wells, Stuart William, "The Schuylkill Navigation and the Girard Canal" (1989). Theses (Historic Preservation). 350. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/350 Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Wells, Stuart William (1989). The Schuylkill Navigation and the Girard Canal. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/350 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Schuylkill Navigation and the Girard Canal Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Wells, Stuart William (1989). The Schuylkill Navigation and the Girard Canal. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This thesis or dissertation is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/350 UNIVERSITY^ PENNSYLVANIA. LIBRARIES THE SCHUYLKILL NAVIGATION AND THE GIRARD CANAL Stuart William -

Coventry Canal

PDF download Boaters' Guides Welcome A note on dimensions data Key to facilities These guides list information we currently The data contained in this guide is our Winding hole (length specified) have on our facilities and stoppages. We estimate of the dimensions of our cannot guarantee complete accuracy and waterways based upon local knowledge Winding hole (full length) so you should also check locally in and expertise. Whilst we anticipate that this advance for anything that is particularly data is reasonably accurate, we cannot vital to your journey. guarantee its precision. Therefore, this Visitor mooring data should only be used as a helpful guide and you should always use your own Information and office judgement taking into account local circumstances at any particular time. Dock and/or slipway Slipway only Services and facilities Water point only Downloaded from canalrivertrust.org.uk on 27 March 2017 1 Trent & Mersey Canal Coventry Canal Trent & Mersey Canal Coventry Canal Fazeley Fradley Coventry Canal 90 Alrewas Croxall Coton in the Elms 18 Overseal 20: Wood End Lock 15: Hunts Lock Fazeley 17 50 16: Keepers Lock 14 Fradley Junction 10 17: Junction Lock 12 16 51: Junction Bridge 88 Edingale13 76 Lullington Fazeley Junction 11 52 15 1 86: Streethay Bridge 19: Shadehouse Lock 84 Whittington 82 Chilcote Huddlesford Junction Elford Haselour Clifton Campville 80 2 78 3 Coventry Canal Thorpe Constantine Coventry Canal Newton Wigginton Newton Regis Austrey 5 4 66 64 8 7 68 Shuttington 70 56 13: Glascote Bottom Lock Glascote 6 Coventry Canal Bitterscote 74 12: Glascote Top Lock 54 52 Weeford Tamworth Fazeley 9 50 Coventry Canal Opening times November 2016 – 31 March Centre and the Barclaycard Arena for the British 2017. -

Premises, Sites Etc Within 30 Miles of Harrington Museum Used for Military Purposes in the 20Th Century

Premises, Sites etc within 30 miles of Harrington Museum used for Military Purposes in the 20th Century The following listing attempts to identify those premises and sites that were used for military purposes during the 20th Century. The listing is very much a works in progress document so if you are aware of any other sites or premises within 30 miles of Harrington, Northamptonshire, then we would very much appreciate receiving details of them. Similarly if you spot any errors, or have further information on those premises/sites that are listed then we would be pleased to hear from you. Please use the reporting sheets at the end of this document and send or email to the Carpetbagger Aviation Museum, Sunnyvale Farm, Harrington, Northampton, NN6 9PF, [email protected] We hope that you find this document of interest. Village/ Town Name of Location / Address Distance to Period used Use Premises Museum Abthorpe SP 646 464 34.8 km World War 2 ANTI AIRCRAFT SEARCHLIGHT BATTERY Northamptonshire The site of a World War II searchlight battery. The site is known to have had a generator and Nissen huts. It was probably constructed between 1939 and 1945 but the site had been destroyed by the time of the Defence of Britain survey. Ailsworth Manor House Cambridgeshire World War 2 HOME GUARD STORE A Company of the 2nd (Peterborough) Battalion Northamptonshire Home Guard used two rooms and a cellar for a company store at the Manor House at Ailsworth Alconbury RAF Alconbury TL 211 767 44.3 km 1938 - 1995 AIRFIELD Huntingdonshire It was previously named 'RAF Abbots Ripton' from 1938 to 9 September 1942 while under RAF Bomber Command control. -

Cropredy Bridge by MISS M

Cropredy Bridge By MISS M. R. TOYNBEE and J. J. LEEMING I IE bridge over the River Chenveff at Cropredy was rebuilt by the Oxford shire County Council in J937. The structure standing at that time was for T the most part comparatively modern, for the bridge, as will be explained later, has been thoroughly altered and reconstructed at least twice (in J780 and 1886) within the last 160 years. The historical associations of the bridge, especiaffy during the Civil War period, have rendered it famous, and an object of pilgrimage, and it seems there fore suitable, on the occasion of its reconstruction, to collect together such details as are known about its origin and history, and to add to them a short account of the Civil War battle of 1644, the historical occurrence for which the site is chiefly famous. The general history of the bridge, and the account of the battle, have been written by Miss Toynbee; the account of the 1937 reconstruction is by Mr. Leeming, who, as engineer on the staff of the Oxfordshire County Council, was in charge of the work. HISTORY OF TIlE BRIDGE' The first record of the existence of a bridge at Cropredy dates, so far as it has been possible to discover, from the year 1312. That there was a bridge in existence before 1312 appears to be pretty certain. Cropredy was a place of some importance in the :\1iddle Ages. It formed part of the possessions of the See of Lincoln, and is entered in Domesday Book as such. 'The Bishop of Lincoln holds Cropelie. -

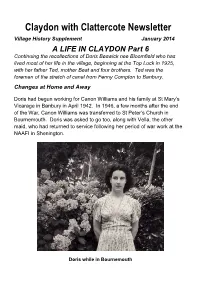

Claydon with Clattercote Newsletter

Claydon with Clattercote Newsletter Village History Supplement January 2014 A LIFE IN CLAYDON Part 6 Continuing the recollections of Doris Beswick nee Bloomfield who has lived most of her life in the village, beginning at the Top Lock in 1925, with her father Ted, mother Beat and four brothers. Ted was the foreman of the stretch of canal from Fenny Compton to Banbury. Changes at Home and Away Doris had begun working for Canon Williams and his family at St Mary’s Vicarage in Banbury in April 1942. In 1946, a few months after the end of the War, Canon Williams was transferred to St Peter’s Church in Bournemouth. Doris was asked to go too, along with Vella, the other maid, who had returned to service following her period of war work at the NAAFI in Shenington. Doris while in Bournemouth The Vicarage in Bournemouth was much smaller than that in Banbury, as was the household. There was only Canon and Mrs Williams and one of their children. In service, there was just Doris and Vella, with Vella taking on the role of cook, but she would also clean the kitchen and help with polishing the silver while Doris was a maid of all trades. As in Banbury, Mrs Williams frequently helped with the chores. With no handyman, Doris took over some of those tasks, such as cleaning the Bishop’s shoes while Mrs Williams relieved Doris of one of her Banbury jobs of cleaning out the grates and setting and lighting the fires. The girls were allowed to take their time off together and the family would organise their meals themselves and do all of the washing up. -

Clifton Past and Present

Clifton Past and Present L.E. Gardner, 1955 Clifton, as its name would imply, stands on the side of a hill – ‘tun’ or ‘ton’ being an old Saxon word denoting an enclosure. In the days before the Norman Conquest, mills were grinding corn for daily bread and Clifton Mill was no exception. Although there is no actual mention by name in the Domesday Survey, Bishop Odo is listed as holding, among other hides and meadows and ploughs, ‘Three Mills of forty one shillings and one hundred ells, in Dadintone’. (According to the Rev. Marshall, an ‘ell’ is a measure of water.) It is quite safe to assume that Clifton Mill was one of these, for the Rev. Marshall, who studied the particulars carefully, writes, ‘The admeasurement assigned for Dadintone (in the survey) comprised, as it would seem, the entire area of the parish, including the two outlying townships’. The earliest mention of the village is in 1271 when Philip Basset, Baron of Wycomb, who died in 1271, gave to the ‘Prior and Convent of St Edbury at Bicester, lands he had of the gift of Roger de Stampford in Cliftone, Heentone and Dadyngtone in Oxfordshire’. Another mention of Clifton is in 1329. On April 12th 1329, King Edward III granted a ‘Charter in behalf of Henry, Bishop of Lincoln and his successors, that they shall have free warren in all their demesne, lands of Bannebury, Cropperze, etc. etc. and Clyfton’. In 1424 the Prior and Bursar of the Convent of Burchester (Bicester) acknowledged the receipt of thirty-seven pounds eight shillings ‘for rent in Dadington, Clyfton and Hampton’. -

Oxfordshire Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by Bride’s Parish Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1635 Gerrard, Ralph --- Eustace, Bridget --- 1635 Saunders, William Caversham Payne, Judith --- 1635 Lydeat, Christopher Alkerton Micolls, Elizabeth --- 1636 Hilton, Robert Bloxham Cook, Mabell --- 1665 Styles, William Whatley Small, Simmelline --- 1674 Fletcher, Theodore Goddington Merry, Alice --- 1680 Jemmett, John Rotherfield Pepper Todmartin, Anne --- 1682 Foster, Daniel --- Anstey, Frances --- 1682 (Blank), Abraham --- Devinton, Mary --- 1683 Hatherill, Anthony --- Matthews, Jane --- 1684 Davis, Henry --- Gomme, Grace --- 1684 Turtle, John --- Gorroway, Joice --- 1688 Yates, Thos Stokenchurch White, Bridgett --- 1688 Tripp, Thos Chinnor Deane, Alice --- 1688 Putress, Ricd Stokenchurch Smith, Dennis --- 1692 Tanner, Wm Kettilton Hand, Alice --- 1692 Whadcocke, Deverey [?] Burrough, War Carter, Elizth --- 1692 Brotherton, Wm Oxford Hicks, Elizth --- 1694 Harwell, Isaac Islip Dagley, Mary --- 1694 Dutton, John Ibston, Bucks White, Elizth --- 1695 Wilkins, Wm Dadington Whetton, Ann --- 1695 Hanwell, Wm Clifton Hawten, Sarah --- 1696 Stilgoe, James Dadington Lane, Frances --- 1696 Crosse, Ralph Dadington Makepeace, Hannah --- 1696 Coleman, Thos Little Barford Clifford, Denis --- 1696 Colly, Robt Fritwell Kilby, Elizth --- 1696 Jordan, Thos Hayford Merry, Mary --- 1696 Barret, Chas Dadington Hestler, Cathe --- 1696 French, Nathl Dadington Byshop, Mary --- Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by