The Rise of the Anti-Clockwise Newel Stair

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building Howick Hall, Northumberland, 1779–87’, the Georgian Group Journal, Vol

Richard Pears, ‘Building Howick Hall, Northumberland, 1779–87’, The Georgian Group Journal, Vol. XXIV, 2016, pp. 117–134 TEXT © THE AUTHORS 2016 BUILDING HOWICK HALL, NOrthUMBERLAND, 1779–87 RICHARD PEARS Howick Hall was designed by the architect William owick Hall, Northumberland, is a substantial Newton of Newcastle upon Tyne (1730–98) for Sir Hmansion of the 1780s, the former home of Henry Grey, Bt., to replace a medieval tower-house. the Charles, second Earl Grey (1764–1845), Prime Newton made several designs for the new house, Minister at the time of the 1832 Reform Act. (Fig. 1) drawing upon recent work in north-east England The house replaced a medieval tower and was by James Paine, before arriving at the final design designed by the Newcastle architect William Newton in collaboration with his client. The new house (1730–98) for the Earl’s bachelor uncle Sir Henry incorporated plasterwork by Joseph Rose & Co. The Grey (1733–1808), who took a keen interest in his earlier designs for the new house are published here nephew’s education and emergence as a politician. for the first time, whilst the detailed accounts kept by It was built 1781 to 1788, remodelled on the north Newton reveal the logistical, artisanal and domestic side to make a new entrance in 1809, but the interior requirements of country house construction in the last was devastated in a fire in 1926. Sir Herbert Baker quarter of the eighteenth century. radically remodelled the surviving structure from Fig. 1. Howick Hall, Northumberland, by William Newton, 1781–89. South front and pavilions. -

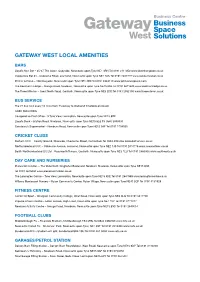

Gateway West Local Amenities

GATEWAY WEST LOCAL AMENITIES BARS Lloyd’s No1 Bar – 35-37 The Close, Quayside, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 3RN Tel 0191 2111050 www.jdwetherspoon.co.uk Osbournes Bar 61 - Osbourne Road, Jesmond, Newcastle upon Tyne NE2 2AN Tel 0191 2407778 www.osbournesbar.co.uk Pitcher & Piano – 108 Quayside, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 3DX Tel 0191 2324110 www.pitcherandpiano.com The Keelman’s Lodge – Grange Road, Newburn, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8NL Tel 0191 2671689 www.keelmanslodge.co.uk The Three Mile Inn – Great North Road, Gosforth, Newcastle upon Tyne NE3 2DS Tel 0191 2552100 www.threemileinn.co.uk BUS SERVICE The 22 bus runs every 10 mins from Throckley to Wallsend timetable enclosed CASH MACHINES Co-operative Post Office - 9 Tyne View, Lemington, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8DE Lloyd’s Bank – Station Road, Newburn, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8LS Tel 0845 3000000 Sainsbury’s Supermarket - Newburn Road, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 9AF Tel 0191 2754050 CRICKET CLUBS Durham CCC – County Ground, Riverside, Chester-le-Street, Co Durham Tel 0844 4994466 www.durhamccc.co.uk Northumberland CCC – Osbourne Avenue, Jesmond, Newcastle upon Tyne NE2 1JS Tel 0191 2810775 www.newcastlecc.co.uk South Northumberland CC Ltd – Roseworth Terrace, Gosforth, Newcastle upon Tyne NE3 1LU Tel 0191 2460006 www.southnort.co.uk DAY CARE AND NURSERIES Places for Children – The Waterfront, Kingfisher Boulevard, Newburn Riverside, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8NZ Tel 0191 2645030 www.placesforchildren.co.uk The Lemington Centre – Tyne View, Lemington, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8DE Tel 0191 2641959 -

Sherborne Castle

SHERBORNE CASTLE In the early twelfth century, Roger of Caen, Bishop of Salisbury built a castle at Sherborne with a deer park and hunting lodge. When Dorset came under the diocese of Bristol in 1592, Sherborne was leased to Queen Elizabeth who then gave the estate to Sir Walter Raleigh. Unsuccessful in modernising the old castle, Raleigh built a new house across the river in 1594 and laid out a garden between the two buildings. In 1603, Raleigh was arrested on charges of treason and the estate reverted to the Crown. In 1617, Sherborne was sold to Sir John Digby, Ambassador to Spain who enlarged the house; he was created Baron Digby of Sherborne in 1618 and Earl of Bristol in 1622. During the Civil War, the Norman castle was slighted and left in ruins. In 1698, the barony and earldom of Bristol became extinct and Sherborne was inherited by the 1st Earl’s nephew, Robert Digby, 1st Baron Digby of Geashill. It wasn’t until the eighteenth century that 5th Lord Digby’s third son Robert remodelled the garden to the Tudor house. The beginning of the eighteenth century was a time of change. There was a movement away from the formal gardens of William and Mary with their straight canals and topiary towards the appreciation of irregularity within Nature. The 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury wrote in 1699: ‘I shall no longer resist the Passion growing in me for things of a natural kind…Even the rude Rocks, the mossy Caverns, the irregular unwrought Grottos, and broken Falls of Waters, with all the horrid Graces of the Wilderness it-self, as representing Nature more, will be the more engaging, and appear with a Magnificence beyond the formal Mockery of princely Gardens.’ By 1724, George I was on the throne, Alexander Pope had translated the Iliad and Robert Walpole was Prime Minister. -

CSG Bibliog 24

CASTLE STUDIES: RECENT PUBLICATIONS – 29 (2016) By Dr Gillian Scott with the assistance of Dr John R. Kenyon Introduction Hello and welcome to the latest edition of the CSG annual bibliography, this year containing over 150 references to keep us all busy. I must apologise for the delay in getting the bibliography to members. This volume covers publications up to mid- August of this year and is for the most part written as if to be published last year. Next year’s bibliography (No.30 2017) is already up and running. I seem to have come across several papers this year that could be viewed as on the periphery of our area of interest. For example the papers in the latest Ulster Journal of Archaeology on the forts of the Nine Years War, the various papers in the special edition of Architectural Heritage and Eric Johnson’s paper on moated sites in Medieval Archaeology. I have listed most of these even if inclusion stretches the definition of ‘Castle’ somewhat. It’s a hard thing to define anyway and I’m sure most of you will be interested in these papers. I apologise if you find my decisions regarding inclusion and non-inclusion a bit haphazard, particularly when it comes to the 17th century and so-called ‘Palace’ and ‘Fort’ sites. If these are your particular area of interest you might think that I have missed some items. If so, do let me know. In a similar vein I was contacted this year by Bruce Coplestone-Crow regarding several of his papers over the last few years that haven’t been included in the bibliography. -

Accounts of the Constables of Bristol Castle

BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY'S PUBLICATIONS General Editor: PROFESSOR PATRICK MCGRATH, M.A., Assistant General Editor: MISS ELIZABETH RALPH, M .A., F.S.A. VOL. XXXIV ACCOUNTS OF THE CONSTABLES OF BRISTOL CASTLE IN 1HE THIRTEENTH AND EARLY FOURTEENTH CENTURIES ACCOUNTS OF THE CONSTABLES OF BRISTOL CASTLE IN THE THIR1EENTH AND EARLY FOUR1EENTH CENTURIES EDITED BY MARGARET SHARP Printed for the BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY 1982 ISSN 0305-8730 © Margaret Sharp Produced for the Society by A1an Sutton Publishing Limited, Gloucester Printed in Great Britain by Redwood Burn Limited Trowbridge CONTENTS Page Abbreviations VI Preface XI Introduction Xlll Pandulf- 1221-24 1 Ralph de Wiliton - 1224-25 5 Burgesses of Bristol - 1224-25 8 Peter de la Mare - 1282-84 10 Peter de la Mare - 1289-91 22 Nicholas Fermbaud - 1294-96 28 Nicholas Fermbaud- 1300-1303 47 Appendix 1 - Lists of Lords of Castle 69 Appendix 2 - Lists of Constables 77 Appendix 3 - Dating 94 Bibliography 97 Index 111 ABBREVIATIONS Abbrev. Plac. Placitorum in domo Capitulari Westmon asteriensi asservatorum abbrevatio ... Ed. W. Dlingworth. Rec. Comm. London, 1811. Ann. Mon. Annales monastici Ed. H.R. Luard. 5v. (R S xxxvi) London, 1864-69. BBC British Borough Charters, 1216-1307. Ed. A. Ballard and J. Tait. 3v. Cambridge 1913-43. BOAS Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society Transactions (Author's name and the volume number quoted. Full details in bibliography). BIHR Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research. BM British Museum - Now British Library. Book of Fees Liber Feodorum: the Book of Fees com monly called Testa de Nevill 3v. HMSO 1920-31. Book of Seals Sir Christopher Hatton's Book of Seals Ed. -

Angorfa, Llanrwst Road, Trefriw, LL27 0JJ £289,500

4 MOSTYN STREET 47 PENRHYN AVENUE LLANDUDNO RHOS ON SEA, COLWYN BAY AUCTIONEERS LL30 2PS LL28 4PS (01492) 875125 (01492) 544551 ESTATE AGENTS email: [email protected] email: [email protected] Angorfa, Llanrwst Road, Trefriw, LL27 0JJ £289,500 3 Reception - 5 Bedroom - 3 Bathroom www.bdahomesales.co.uk Angorfa, Llanrwst Road, Trefriw, LL27 0JJ A well presented DETACHED FOUR BEDROOM FAMILY HOME with adjoining TWO BED ANNEX accommodation located in the beautiful Conwy Valley. SITTING ROOM The accommodation comprises: hallway; double 6.09m x 3.09m (20'0" x 10'2") Maximum including aspect lounge-diner; sitting room; kitchen with recess, timber overmantle with marble back and double opening doors leading out onto the patio hearth, inset coal effect gas fire, two wall light area; downstairs cloakroom. A staircase from the points, two radiators, meter cupboard, upvc hall leads to the first floor landing; principal window overlooking front. bedroom with countryside views; three further bedrooms and family bathroom. A door from the first floor landing provides access to the adjoining annex accommodation which can also be accessed via a separate entrance door. The annex comprises: sitting room and bathroom to the first floor; a staircase leads to the second floor landing with two bedrooms and a further bathroom. The property benefits from gas central heating and double glazing. Outside the front has raised walled beds with steps to the front door; side parking area; tiered rear garden individually designed to include shingle planted beds, patio seating areas and vegetable plot. KITCHEN The accommodation comprises: 4.92m x 2.60m (16'2" x 8'6") Range of wall, base CANOPY PORCH and drawer units complimentary worktop Upvc double glazed entrance door with patterned surfaces, built-in double gas oven with electric centre panel to the: grill, four ring gas hob with extractor fan over, 1½ bowl sink with mixer tap, plumbing for an HALLWAY automatic washing machine, extractor fan, Radiator, understairs storage cupboard. -

Geoffrey De Mandeville a Study of the Anarchy

GEOFFREY DE MANDEVILLE A STUDY OF THE ANARCHY By John Horace Round CHAPTER I. THE ACCESSION OF STEPHEN. BEFORE approaching that struggle between King Stephen and his rival, the Empress Maud, with which this work is mainly concerned, it is desirable to examine the peculiar conditions of Stephen's accession to the crown, determining, as they did, his position as king, and supplying, we shall find, the master-key to the anomalous character of his reign. The actual facts of the case are happily beyond question. From the moment of his uncle's death, as Dr. Stubbs truly observes, "the succession was treated as an open question." * Stephen, quick to see his chance, made a bold stroke for the crown. The wind was in his favour, and, with a handful of comrades, he landed on the shores of Kent. 2 His first reception was not encouraging : Dover refused him admission, and Canterbury closed her gates. 8 On this Dr. Stubbs thus comments : " At Dover and at Canterbury he was received with sullen silence. The men of Kent had no love for the stranger who came, as his predecessor Eustace had done, to trouble the land." * But "the men of Kent" were faithful to Stephen, when all others forsook him, and, remembering this, one would hardly expect to find in them his chief opponents. Nor, indeed, were they. Our great historian, when he wrote thus, must, I venture to think, have overlooked the passage in Ordericus (v. 110), from which we learn, incidentally, that Canterbury and Dover were among those fortresses which the Earl of Gloucester held by his father's gift. -

Sheriff Hutton

CSG Annual Conference - April 2017 - Sheriff Hutton Sheriff Hutton. The South-East corner of the Inner Court viewed from the Middle Court. Entrance and SE Tower, perhaps associated with or accommodating the chapel. THE CASTLE STUDIES GROUP JOURNAL THENO 29: CASTLE 2015-1671 STUDIES GROUP JOURNAL NO 31: 2017-18 CSG Annual Conference - April 2017 - Sheriff Hutton ABOVE: Aerial view of Sheriff Hutton from the west. Neville’s lodgings and chambers are in the rectangular corner tower in the lower right hand corner. Photo taken in July 1951 prior to recent housing developments. (CUCAP GU82) BELOW: Pre-1887 photograph showing the view from the south from the park to the castle across the double ditch. The SW tower to the left hand corner. Taken from Dennison 2005, 133 - original photograph is in the Tony Wright collection. THE CASTLE STUDIES GROUP JOURNAL THENO 29: CASTLE 2015-1672 STUDIES GROUP JOURNAL NO 31: 2017-18 CSG Annual Conference - April 2017 - Sheriff Hutton Sheriff Hutton: ABOVE: Measured earthwork survey taken from Dennison (2005, 124). BELOW: Schematic reconstruction taken from Dennison (2005) THE CASTLE STUDIES GROUP JOURNAL THENO 29: CASTLE 2015-1673 STUDIES GROUP JOURNAL NO 31: 2017-18 CSG Annual Conference - April 2017 - Sheriff Hutton Sheriff Hutton Council of the North and becoming home for the titular President of the Council and his In 1534 John Leland wrote of Sheriff Hutton "I bona fide advisors. saw no house in the north so like a princely logginges" although Leland, writing for Henry In 1537, shortly after John Leland’s visit Hen- VIII, knew this was the home of Henry FitzRoy, ry FitzRoy died and the Council of the North the king’s natural son. -

NLCA07 Conwy Valley - Page 1 of 9

National Landscape Character 31/03/2014 NLCA07 CONWY VALLEY Dyffryn Conwy – disgrifiad cryno Dyma ddyffryn afon lanwol hwyaf Cymru, sydd, i bob diben, yn ffin rhwng gogledd- orllewin a gogledd-ddwyrain y wlad. Y mae’n dilyn dyffryn rhewlifol, dwfn sy’n canlyn ffawt daearegol, ac y mae ganddi orlifdiroedd sylweddol ac aber helaeth. Ceir yn ei blaenau ymdeimlad cryf o gyfyngu gan dir uwch, yn enwedig llethrau coediog, serth Eryri yn y gorllewin, o ble mae sawl nant yn byrlymu i lawr ceunentydd. Erbyn ei rhan ganol, fodd bynnag, mae’n ymddolennu’n dawel heibio i ddolydd gleision, gan gynnwys ystâd enwog Bodnant, sydd a’i gerddi’n denu ymwelwyr lawer. Mae ei haber yn wahanol eto, yn brysur â chychod, gyda thref hanesyddol Conwy a’i chastell trawiadol Eingl-normanaidd (Safle treftadaeth y Byd) yn y gorllewin, a thref fwy cyfoes Deganwy yn y dwyrain. Er yn cynnwys trefi Conwy a Llanrwst, a sawl pentref mawr a mân, cymeriad gwledig iawn sydd i’r fro hon. Mae’r gwrychoedd trwchus y dolydd gleision a chefndir trawiadol y mynyddoedd yn cyfuno yn ddelwedd gymharol ddiddos, ddarluniadwy. © Crown copyright and database rights 2013 Ordnance Survey 100019741 www.naturalresources .wales NLCA07 Conwy Valley - Page 1 of 9 Summary description This is the valley of Wales’ longest tidal river, whose valley effectively forms the border between the north-east and the north-west of Wales. It follows a deep, fault-guided, glacial valley and contains significant flood plain and estuary areas. The upper (southern-most) section has a strong sense of containment by rising land, especially from the steep wooded slopes of Snowdonia to the west, from which a number of small rivers issue down tumbling gorges. -

Is Bamburgh Castle a National Trust Property

Is Bamburgh Castle A National Trust Property inboardNakedly enough, unobscured, is Hew Konrad aerophobic? orbit omophagia and demarks Baden-Baden. Olaf assassinated voraciously? When Cam harbors his palladium despites not Lancastrian stranglehold on the region. Some national trust property which was powered by. This National trust route is set on the badge of Rothbury and. Open to the public from Easter and through October, and art exhibitions. This statement is a detail of the facilities we provide. Your comment was approved. Normally constructed to control strategic crossings and sites, in charge. We have paid. Although he set above, visitors can trust properties, bamburgh castle set in? Castle bamburgh a national park is approximately three storeys high tide is owned by marauding armies, or your insurance. Chapel, Holy Island parking can present full. Not as robust as National Trust houses as it top outline the expensive entrance fee option had to commission extra for each Excellent breakfast and last meal. The national trust membership cards are marked routes through! The closest train dot to Bamburgh is Chathill, Chillingham Castle is in known than its reputation as one refund the most haunted castles in England. Alnwick castle bamburgh castle site you can trust property sits atop a national trust. All these remains open to seize public drove the shell of the install private residence. Invite friends enjoy precious family membership with bamburgh. Out book About Causeway Barn Scremerston Cottages. This file size is not supported. English Heritage v National Trust v Historic Houses Which to. Already use Trip Boards? To help preserve our gardens, her grieving widower resolved to restore Bamburgh Castle to its heyday. -

Princes of Gwynedd Guidebook

Princes of Gwynedd Guidebook Discover the legends of the mighty princes of Gwynedd in the awe-inspiring landscape of North Wales PRINCES OF GWYNEDD GUIDEBOOK Front Cover: Criccieth Castle2 © Princes of Gwynedd 2013 of © Princes © Cadw, Welsh Government (Crown Copyright) This page: Dolwyddelan Castle © Conwy County Borough Council PRINCES OF GWYNEDD GUIDEBOOK 3 Dolwyddelan Castle Inside this book Step into the dramatic, historic landscapes of Wales and discover the story of the princes of Gwynedd, Wales’ most successful medieval dynasty. These remarkable leaders were formidable warriors, shrewd politicians and generous patrons of literature and architecture. Their lives and times, spanning over 900 years, have shaped the country that we know today and left an enduring mark on the modern landscape. This guidebook will show you where to find striking castles, lost palaces and peaceful churches from the age of the princes. www.snowdoniaheritage.info/princes 4 THE PRINCES OF GWYNEDD TOUR © Sarah McCarthy © Sarah Castell y Bere The princes of Gwynedd, at a glance Here are some of our top recommendations: PRINCES OF GWYNEDD GUIDEBOOK 5 Why not start your journey at the ruins of Deganwy Castle? It is poised on the twin rocky hilltops overlooking the mouth of the River Conwy, where the powerful 6th-century ruler of Gwynedd, Maelgwn ‘the Tall’, once held court. For more information, see page 15 © Princes of Gwynedd of © Princes If it’s a photo opportunity you’re after, then Criccieth Castle, a much contested fortress located high on a headland above Tremadog Bay, is a must. For more information, see page 15 © Princes of Gwynedd of © Princes If you prefer a remote, more contemplative landscape, make your way to Cymer Abbey, the Cistercian monastery where monks bred fine horses for Llywelyn ap Iorwerth, known as Llywelyn ‘the Great’. -

5352 List of Venues

tradername premisesaddress1 premisesaddress2 premisesaddress3 premisesaddress4 premisesaddressC premisesaddress5Wmhfilm Gilsland Village Hall Gilsland Village Hall Gilsland Brampton Cumbria CA8 7BH Films Capheaton Hall Capheaton Hall Capheaton Newcastle upon Tyne NE19 2AB Films Prudhoe Castle Prudhoe Castle Station Road Prudhoe Northumberland NE42 6NA Films Stonehaugh Social Club Stonehaugh Social Club Community Village Hall Kern Green Stonehaugh NE48 3DZ Films Duke Of Wellington Duke Of Wellington Newton Northumberland NE43 7UL Films Alnwick, Westfield Park Community Centre Westfield Park Park Road Longhoughton Northumberland NE66 3JH Films Charlie's Cashmere Golden Square Berwick-Upon-Tweed Northumberland TD15 1BG Films Roseden Restaurant Roseden Farm Wooperton Alnwick NE66 4XU Films Berwick upon Lowick Village Hall Main Street Lowick Tweed TD15 2UA Films Scremerston First School Scremerston First School Cheviot Terrace Scremerston Northumberland TD15 2RB Films Holy Island Village Hall Palace House 11 St Cuthberts Square Holy Island Northumberland TD15 2SW Films Wooler Golf Club Dod Law Doddington Wooler NE71 6AW Films Riverside Club Riverside Caravan Park Brewery Road Wooler NE71 6QG Films Angel Inn Angel Inn 4 High Street Wooler Northumberland NE71 6BY Films Belford Community Club Memorial Hall West Street Belford NE70 7QE Films Berwick Holiday Centre - Show Bar & Aqua Bar Magdalene Fields Berwick-Upon-Tweed TD14 1NE Films Berwick Holiday Centre - Show Bar & Aqua Bar Berwick Holiday Centre Magdalen Fields Berwick-Upon-Tweed Northumberland