History of the Commission on the Status of Women1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

!Lay, 1911 N11.1

11al. XX11JJJ !lay, 1911 N11.1 Official Organ of l(appa Rappa 6amma Voluine X'XVIII MAY, 19H Number2 6oard of Editors Editor-in-Chief- Mrs. Ralph T. C. Jackson "Hearthstone," Dighton, Mass. Exchange Editor- Mrs. Howard B. Mullin . 842 Ackerman Ave., Syracuse, N.Y (!lnutruta INAUGURAL ADDREss-Virginia C. Gildersleeve . IOI FRIENDS-A Song-Cora Call Whitley ............... .. I07 THE INSTALLATION OF Miss GILDERSLEEVE-Eleanor 1\lfyers w8 PROFESSIONAL OPPORTUNITIES IN HOME ECONOMICS- Flo?'a Rose ............ ................... III THE KAPPA TouR . I I6 PARTHENON . ............... ... .... .. .... .. .. II8 TRuE PAN- HELLENISM ......... ................ I r8 A BROADER FRATERNITY LIFE ....... .. .. ... ...... I I9 WHAT THE WoMEN ARE DOING AT MICHIGAN . .... .. I20 INITIATION REQUIREMENTS . I22 PosT-PLEDGE DAY REFLECTIONS ... .. ... ....... I24 THE SENIOR's Vmw PoiNT ........ ....... ..... I25 THE BLASEE FRATERNITY GIRLS . .......... .. ....... 'I27 EDITORIAL . I 29 CHAPTER LETTERS ...... .. ....... .. ....... ......... I30 ALUMNAE AssociATION REPORTS . .. ..... ... .. ....... I6o I N MEMORIAM . 163 ALUMNAE PERSONALS . I64 ExcHANGES ....... .. ........................... I7I CoLLEGE NoTES .. .. .. .... ........ ........... ... .. .. I83 MAGAZINE NoTES . .............................. ..... I86 Subscription price, one dollar per year. Published four times a year in February, May, October and December by Georg-e Banta, Official Printer to Kappa Kappa Gamma, t65-167 Main Street, Menasha, ·wisconsin. Entered as second class matter November 3, 1910, at the postoffice at Menasha, 'liTis., under the Act of March 3, 1879. Material intended for publication must reach the editor before the first of January, April, September and November. 1J1 rateruity mtrednry ~ranll Qloundl Grand President- MRs . A. H. RoTH, 262 West T enth Street, Erie, Pa. G1·and S ecretary--EvA PowELL, 921 Myrtle Street, Oakland, Cal. Grand Treasnrer-MRs. PARKER. KOLBE, 108 South Union Street, Akron, Ohio Grand Registrar-JuLIETTE G. -

Equality – Development – Peace: Women 60 Years with the United Nations - Hilkka Pietila

PEACE, LITERATURE, AND ART – Vol. II - Equality – Development – Peace: Women 60 Years With the United Nations - Hilkka Pietila EQUALITY – DEVELOPMENT – PEACE: WOMEN 60 YEARS WITH THE UNITED NATIONS Hilkka Pietila Independent researcher and author; Associated with Institute of Development Studies, University of Helsinki, Finland Keywords: United Nations, equality, development, peace, women, empowerment, gender mainstreaming, platform for action, implementation, human rights, gender equality, violence against women, reproductive health and rights, trafficking in women and girls, world conferences, war crimes, peace tables. Contents 1. Prologue – Women in the League of Nations 1.1 Women Were Ready to Act 1.2. The Process Continuing – Experiences Transferring 2. The Founding Mothers of the United Nations 3. New Dimensions in the UN – Economic, Social and Human Rights Issues 3.1. Women’s Site in the UN - Commission on the Status of Women 3.2. Women’s Voice at the Global Arena - the UN World Conferences on Women 4. Human Rights are Women’s Rights 4.1 Traffic in Persons -Women 4.2. A New Human Right - Right to Family Planning 4.3. Convention on the Rights of Women 5. Women Going Global - Beijing Conference 1995 5.1 All issues are women’s issues 5.2. Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing 1995 5.3. Empowerment of Women and Gender Mainstreaming 5.4. From the Battle Field to the Peace Table 6. Celebrating Beijing+10 and Mexico City+30 6.1. Five-year Reviews and Appraisals emerged from Mexico City 6.2. The Global Census Taken for Beijing+10 6.3 Beijing+10 and Millennium Development Goals 6.4. -

A New National Defense: Feminism, Education, and the Quest for “Scientific Brainpower,” 1940-1965

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository A New National Defense: Feminism, Education, and the Quest for “Scientific Brainpower,” 1940-1965 Laura Micheletti Puaca A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2007 Approved by: Jacquelyn Dowd Hall James Leloudis Peter Filene Jerma Jackson Catherine Marshall ©2007 Laura Micheletti Puaca ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii To my parents, Richard and Ann Micheletti, for their unconditional love and encouragement. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS While working on this dissertation, I enjoyed the support and assistance of numerous individuals and organizations. First, I would like to acknowledge those institutions that generously funded my work. A Mowry Research Award from the University of North Carolina’s Department of History and an Off-Campus Research Fellowship from the University of North Carolina’s Graduate School supported this project’s early stages. A Schlesinger Library Dissertation Grant from the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University, as well as a Woodrow Wilson Dissertation Fellowship in Women’s Studies, allowed me to carry out the final phases of research. Likewise, I benefited enormously from a Spencer Foundation Dissertation Fellowship for Research Related to Education, which made possible an uninterrupted year of writing. I am also grateful to the archivists and librarians who assisted me as I made my way though countless documents. The staff at the American Association of University Women Archives, the Columbia University Archives, the Columbia University Rare Book and Manuscript Library, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Archives, the National Federation of Business and Professional Women’s Clubs Archives, the National Archives at College Park, and the Rare and Manuscript Collection at Cornell University provided invaluable guidance. -

The Story of the US Naval Training School (WR) at Hunter College

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Lehman College 1993 Making Waves in the Bronx: The Story of the U.S. Naval Training School (WR) at Hunter College Janet Butler Munch CUNY Lehman College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/le_pubs/195 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] \ 8/:PJ:ORD PARK /3'/(. ·v·o. U.S. NAVAL TRAINING SCHOOL (WR) MAKING WAVES IN THE BRONX: BRONX, NEW YORK 63, N,Y. * THE STORY OF THE U.S. NAVAL t TRAINING SCHOOL .(WR) AT HUNTER COLLEGE Janet Butler Munch Severe manpower shortages, which resulted from fighting a war on two fronts, forced U.S. Navy officials to enlist women in· World War II. Precedent already existed for women serving in the ~ Navy since 11,275 womenl had contributed to the war effort in LJ ::i World War I. Women at that time received no formal indoctrina ~ ~ tion nor was any fom1al organization established. ~ 'q: There was considerable opposition to admitting women into ~ "this man's Navy" during World War II and a Women's Reserve LJ::::=========='J ~ had few champions among the Navy's higher echelons. Congress, WEST /9SYI STREET 0 public interest, and even advocacy from the National Federation Ir========~~IQ of Business and Professional Women's Clubs pressured the Navy ARMORY ..., IN 80llN/J$ ON .SPl:C'JAJ. -

As Desigualdades Entre Mulheres E Homens No Mercado De Trabalho E a Sua Medição: Contributos De Um Novo Indicador Composto Para Os Países Da Ue-28

Carina Raquel Mendes Jordão AS DESIGUALDADES ENTRE MULHERES E HOMENS NO MERCADO DE TRABALHO E A SUA MEDIÇÃO: CONTRIBUTOS DE UM NOVO INDICADOR COMPOSTO PARA OS PAÍSES DA UE-28 Tese de Doutoramento em Sociologia: Relações de Trabalho, Desigualdades Sociais e Sindicalismo, orientada pela Professora Doutora Virgínia Ferreira e pela Professora Doutora Carla Amado e apresentada à Faculdade de Economia da Universidade de Coimbra Coimbra, outubro de 2017 Carina Raquel Mendes Jordão As Desigualdades entre Mulheres e Homens no Mercado de Trabalho e a sua Medição: Contributos de um Novo Indicador Composto para os Países da UE-28 Tese de Doutoramento em Sociologia: Relações de Trabalho, Desigualdades Sociais e Sindicalismo, apresentada à Faculdade de Economia da Universidade de Coimbra para obtenção do grau de Doutora Orientadoras: Prof. Doutora Virgínia Ferreira e Prof. Doutora Carla Amado Coimbra, outubro de 2017 Ilustração da capa: Rute Jordão Para a Simone e para a Rute, as minhas pessoas favoritas. iii AGRADECIMENTOS à Professora Doutora Carla Amado e à Professora Doutora Virgínia Ferreira: agradeço o apoio incondicional com que me brindaram nesta longa e dura caminhada. ao Nelson Filipe, pela presença e apoio técnico, muito obrigada. aos meus familiares, amigas e amigos de toda uma vida e de tantas vidas: obrigada pelo carinho e pela compreensão. do São as Pessoas como Tu São as pessoas como tu que fazem com que o nada queira dizer-nos algo, as coisas vulgares se tornem coisas importantes e as preocupações maiores sejam de facto mais pequenas. São as pessoas como tu que dão outra dimensão aos dias, transformando a chuva em delirante orvalho e fazendo do inverno uma estação de rosas rubras. -

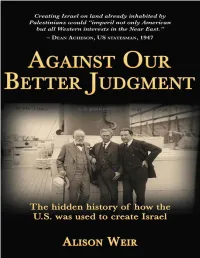

Against Our Better Judgment: the Hidden History of How the U.S. Was

Against Our Better Judgment The hidden history of how the U.S. was used to create Israel ALISON WEIR Copyright © 2014 Alison Weir All rights reserved. DEDICATION To Laila, Sarah, and Peter CONTENTS Aknowledgments Preface Chapter One: How the U.S. “Special Relationship” with Israel came about Chapter Two: The beginnings Chapter Three: Louis Brandeis, Zionism, and the “Parushim” Chapter Four: World War I & the Balfour Declaration Chapter Five: Paris Peace Conference 1919: Zionists defeat calls for self- determination Chapter Six: Forging an “ingathering” of all Jews Chapter Seven: The modern Israel Lobby is born Chapter Eight: Zionist Colonization Efforts in Palestine Chapter Nine: Truman Accedes to Pro-Israel Lobby Chapter Ten: Pro-Israel Pressure on General Assembly Members Chapter Eleven: Massacres and the Conquest of Palestine Chapter Twelve: U.S. front groups for Zionist militarism Chapter Thirteen: Infiltrating displaced person’s camps in Europe to funnel people to Palestine Chapter Fourteen: Palestinian refugees Chapter Fifteen: Zionist influence in the media Chapter Sixteen: Dorothy Thompson, played by Katharine Hepburn & Lauren Bacall Works Cited Further Reading Endnotes ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am extremely grateful to Katy, who plowed through my piles of obscure books and beyond to check it; to Sarah, whose design so enhanced it; to Monica, whose splendid work kept things together; and to the special, encouraging friends (you know who you are) who have made this all possible. Above all, I am profoundly grateful to the authors and editors who have produced superb work on this issue for so many years, many receiving little personal gain despite the excellence and dedication of their labors. -

Volume4 Issue7(1)

Volume 4, Issue 7(1), July 2015 International Journal of Multidisciplinary Educational Research Published by Sucharitha Publications 8-21-4,Saraswathi Nivas,Chinna Waltair Visakhapatnam – 530 017 Andhra Pradesh – India Email: [email protected] Website: www.ijmer.in Editorial Board Editor-in-Chief Dr.K. Victor Babu Faculty, Department of Philosophy Andhra University – Visakhapatnam - 530 003 Andhra Pradesh – India EDITORIAL BOARD MEMBERS Prof. S.Mahendra Dev Prof. Fidel Gutierrez Vivanco Vice Chancellor Founder and President Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Escuela Virtual de Asesoría Filosófica Research Lima Peru Mumbai Prof. Igor Kondrashin Prof.Y.C. Simhadri The Member of The Russian Philosophical Vice Chancellor, Patna University Society Former Director The Russian Humanist Society and Expert of Institute of Constitutional and Parliamentary The UNESCO, Moscow, Russia Studies, New Delhi & Formerly Vice Chancellor of Dr. Zoran Vujisiæ Benaras Hindu University, Andhra University Rector Nagarjuna University, Patna University St. Gregory Nazianzen Orthodox Institute Universidad Rural de Guatemala, GT, U.S.A Prof. (Dr.) Sohan Raj Tater Former Vice Chancellor Singhania University, Rajasthan Prof.U.Shameem Department of Zoology Andhra University Visakhapatnam Prof.K.Sreerama Murty Department of Economics Dr. N.V.S.Suryanarayana Andhra University - Visakhapatnam Dept. of Education, A.U. Campus Vizianagaram Prof. K.R.Rajani Department of Philosophy Dr. Kameswara Sharma YVR Andhra University – Visakhapatnam Asst. Professor Dept. of Zoology Prof. P.D.Satya Paul Sri. Venkateswara College, Delhi University, Department of Anthropology Delhi Andhra University – Visakhapatnam I Ketut Donder Prof. Josef HÖCHTL Depasar State Institute of Hindu Dharma Department of Political Economy Indonesia University of Vienna, Vienna & Ex. Member of the Austrian Parliament Prof. -

50 Years of Funding GWI Thanks VGIF for Its Continuing Support

Photo courtesy Louise McLeod courtesyPhoto Louise 1969 - 2019 50 years of Funding GWI thanks VGIF for its continuing support Graduate Women International Chemin du Grand-Montfleury, 48 CH-1290 Versoix, Switzerland Tel: +41 (0) 22 731 23 80 www.graduatewomen.org The Global Impact of VGIF Funding and IFUW / GWI 1969 - 2019 Argentina Finland Nigeria Australia France Pakistan Austria Ghana Philippines Burkina Faso Hungary Russia Burundi India Rwanda Cambodia Ireland Sierra Leone Cameroon Kenya South Africa Canada Korea Sri Lanka Croatia Japan Turkey Egypt Mexico Uganda El Salvador Nepal Vanuatu Estonia Netherlands Zimbabwe Fiji New Zealand GWI thanks VGIF for 50 years of continuing support ©2019 Page 2 VGIF and IFUW / GWI In 1964, the International Federation of University Women (IFUW) held a seminar at Makere University in Kampala, Uganda. Eighteen women representing university women or college graduates from Sub-Sahara Africa joined with seven colleagues from Europe and North and South America to discuss the special needs of women in Africa. They were particularly concerned with the long-range ways and means by which women might achieve a more signifi- cant role in the development of Africa. IFUW members and leaders continued to discuss the role university wom- en might play in providing leadership to identify pressing needs and then do something about these needs not only in Africa but also in Asia and in South America. Their premise was that "if comparatively small sums of money might be available to national or local associations of university women or other women's groups, universities or individuals to undertake imaginative and constructive programs planned by them in their countries or areas; much could be accomplished by broad educational means." 1969 Dr. -

The Roots of the U.S.-Israel Relationship: How the Cold War Tensions Played a Role in U.S

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2013 The Roots of the U.S.-Israel Relationship: How the Cold War Tensions Played a Role in U.S. Foreign Policy in the Middle East Ariel Gomberg Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the History Commons, International Relations Commons, and the Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies Commons Recommended Citation Gomberg, Ariel, "The Roots of the U.S.-Israel Relationship: How the Cold War Tensions Played a Role in U.S. Foreign Policy in the Middle East" (2013). Honors Theses. 670. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/670 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Roots of the U.S.-Israel Relationship: How the Cold War Tensions Played A Role in U.S. Foreign Policy in the Middle East By, Ariel R. Gomberg Senior Thesis Submitted In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in the Department of History UNION COLLEGE June, 2013 Abstract Today the relationship between the United States and Israel includes multiple bi-lateral initiatives in the military, industrial, and private sectors. Israel is Americas most established ally in the Middle East and the two countries are known to possess a “special relationship” highly valued by the United States. Although diplomatic relations between the two countries drive both American and Israeli foreign policy in the Middle East today, following the establishment of the State of Israel the United States originally did not advance major aid and benefits to the new state. -

MINUTES the First Regular Meeting of the University Senate for the Year 1932-33 Was Held in the Library of the Engineering Building, Thursday, October 20, 1932

Year 1932-33 No.1 UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA THE SENATE MINUTES The first regular meeting of the University Senate for the year 1932-33 was held in the Library of the Engineering Building, Thursday, October 20, 1932. Seventy-two members responded to roll call. The following items were presented for consideration by the Committee on Business and Rules and action was taken as indicated. I. THE MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF FEBRUARY 18, 1932 Approved II. SENATE ROSTER FOR 1932-33 Voting List Akerman, John. D. Blitz, Anne D. Alderman, W. H. Boardman, C. W. Allison, John H. Bollman, J. L. (Rochester) Alway, Frederick J. Boss, Andrew Anderson, John E. Boss, William Anderson, William Boyd, Willard L. Appleby, W. R. Boyden, Edward A. Arjona, Carlos Boynton, Ruth E. Arnal, Leon E. Braasch, W. F. (Rochester) Arny, Albert C. Brekhus, Peter J. Bachman, Gustav Brierley, Wilfrid G. Bailey, Clyde H. *Brink, Raymond W. Balfour, D. C. (Rochester) Brooke, William E. Barton, Francis B. Brown, Clara Bass, Frederic H. Brown, Edgar D. Bassett, Louis B. Brueckner, Leo J. Beach, Joseph Bryant, John M. Bell, Elexious T. Buchta, J. W. Benjamin, Harold R. Burkhard, Oscar C. *Berglund, Hilding Burr, George O. tBierman, B. W. Burt, Alfred L. Biester, Alice Burton, S. Chatwood Bieter, Raymond N. Bush, Jol:n N. D. Bird, Charles Bussey, William H. Blakey, Roy G. Butters, Frederic K. Blegen, Theodore Casey, Ralph D. Chapin, F. Stuart French, Robert W. Cherry, Wilbur Garey, L. F. Cheyney, Edward G. Garver, Frederic B. ( Child, Alice M. Geiger, Isaac W. Christensen, Jonas J. Glockler, George Christianson, Peter Goldstein, Harriet Clawson, Benjamin J. -

Introduction to Radical Teacher's 100Th Issue

RT 100 Anniversary Issue ISSN: 1941-0832 Introduction to Radical Teacher’s 100th Issue by Michael Bennett, Linda Dittmar, and Paul Lauter RT 100 Anniversary Issue RADICAL TEACHER 1 http://radicalteacher.library.pitt.edu No. 100 (Fall 2014) DOI 10.5195/rt.2014.146 o acknowledge and celebrate the 100th issue of goals, or some of them; but the provenance suggested a Radical Teacher, we are reprinting selected kind of sectarianism we wished then, and now, to avoid. essays from our very first issue (December T In the second issue, the subtitle of The Radical 1975) through our last year as a print journal (2012). Teacher was gone. Beginning with the third issue, the Though the selection process was never entirely clear or definite article disappeared. Our first book review, of agreed upon, we have tried to choose articles that reflect Editorial Group member Dick Ohmann’s English in America, Radical Teacher’s focus on class, race, and appeared in issue 3, along with a spirited exchange gender/sexuality, as well as on the socio-economic between the author and other board members concerning contexts of education and educational institutions, audience: the efficacy of reaching out to liberals as primarily but not exclusively in the United States. We also opposed to rallying fellow radicals. A feature called “News wanted some essays that emphasized theory and some for Educational Workers” began with issue 4. Both this that emphasized practice, always hoping that these foci feature and book reviews have been part of the journal came together as praxis. We tried to balance historical ever since. -

Lobbies, Refugees, and Governments| a Study of the Role of the Displaced Persons in the Creation of the State of Israel

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1988 Lobbies, refugees, and governments| A study of the role of the displaced persons in the creation of the state of Israel James Daryl Clowes The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Clowes, James Daryl, "Lobbies, refugees, and governments| A study of the role of the displaced persons in the creation of the state of Israel" (1988). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 2867. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/2867 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 THIS IS AN UNPUBLISHED MANUSCRIPT IN WHICH COPYRIGHT SUBSISTS. ANY FURTHER REPRINTING OF ITS CONTENTS MUST BE APPROVED BY THE AUTHOR, MANSFIELD LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA DATE : 1988 LOBBIES, REFUGEES, and GOVERNMENTS: A Study of the Role of the Displaced Persons in the Creation of the State of Israel By James Daryl Clowes B.A., University of Montana, 1981 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Montana 1988 Approved Chairman, Board of xammers De"Sn, Graduate ScnSol ' '^ x 11 i / •• -C/ 5P Date UMI Number: EP34336 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted.