Downloaded License

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

!Lay, 1911 N11.1

11al. XX11JJJ !lay, 1911 N11.1 Official Organ of l(appa Rappa 6amma Voluine X'XVIII MAY, 19H Number2 6oard of Editors Editor-in-Chief- Mrs. Ralph T. C. Jackson "Hearthstone," Dighton, Mass. Exchange Editor- Mrs. Howard B. Mullin . 842 Ackerman Ave., Syracuse, N.Y (!lnutruta INAUGURAL ADDREss-Virginia C. Gildersleeve . IOI FRIENDS-A Song-Cora Call Whitley ............... .. I07 THE INSTALLATION OF Miss GILDERSLEEVE-Eleanor 1\lfyers w8 PROFESSIONAL OPPORTUNITIES IN HOME ECONOMICS- Flo?'a Rose ............ ................... III THE KAPPA TouR . I I6 PARTHENON . ............... ... .... .. .... .. .. II8 TRuE PAN- HELLENISM ......... ................ I r8 A BROADER FRATERNITY LIFE ....... .. .. ... ...... I I9 WHAT THE WoMEN ARE DOING AT MICHIGAN . .... .. I20 INITIATION REQUIREMENTS . I22 PosT-PLEDGE DAY REFLECTIONS ... .. ... ....... I24 THE SENIOR's Vmw PoiNT ........ ....... ..... I25 THE BLASEE FRATERNITY GIRLS . .......... .. ....... 'I27 EDITORIAL . I 29 CHAPTER LETTERS ...... .. ....... .. ....... ......... I30 ALUMNAE AssociATION REPORTS . .. ..... ... .. ....... I6o I N MEMORIAM . 163 ALUMNAE PERSONALS . I64 ExcHANGES ....... .. ........................... I7I CoLLEGE NoTES .. .. .. .... ........ ........... ... .. .. I83 MAGAZINE NoTES . .............................. ..... I86 Subscription price, one dollar per year. Published four times a year in February, May, October and December by Georg-e Banta, Official Printer to Kappa Kappa Gamma, t65-167 Main Street, Menasha, ·wisconsin. Entered as second class matter November 3, 1910, at the postoffice at Menasha, 'liTis., under the Act of March 3, 1879. Material intended for publication must reach the editor before the first of January, April, September and November. 1J1 rateruity mtrednry ~ranll Qloundl Grand President- MRs . A. H. RoTH, 262 West T enth Street, Erie, Pa. G1·and S ecretary--EvA PowELL, 921 Myrtle Street, Oakland, Cal. Grand Treasnrer-MRs. PARKER. KOLBE, 108 South Union Street, Akron, Ohio Grand Registrar-JuLIETTE G. -

A New National Defense: Feminism, Education, and the Quest for “Scientific Brainpower,” 1940-1965

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository A New National Defense: Feminism, Education, and the Quest for “Scientific Brainpower,” 1940-1965 Laura Micheletti Puaca A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2007 Approved by: Jacquelyn Dowd Hall James Leloudis Peter Filene Jerma Jackson Catherine Marshall ©2007 Laura Micheletti Puaca ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii To my parents, Richard and Ann Micheletti, for their unconditional love and encouragement. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS While working on this dissertation, I enjoyed the support and assistance of numerous individuals and organizations. First, I would like to acknowledge those institutions that generously funded my work. A Mowry Research Award from the University of North Carolina’s Department of History and an Off-Campus Research Fellowship from the University of North Carolina’s Graduate School supported this project’s early stages. A Schlesinger Library Dissertation Grant from the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University, as well as a Woodrow Wilson Dissertation Fellowship in Women’s Studies, allowed me to carry out the final phases of research. Likewise, I benefited enormously from a Spencer Foundation Dissertation Fellowship for Research Related to Education, which made possible an uninterrupted year of writing. I am also grateful to the archivists and librarians who assisted me as I made my way though countless documents. The staff at the American Association of University Women Archives, the Columbia University Archives, the Columbia University Rare Book and Manuscript Library, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Archives, the National Federation of Business and Professional Women’s Clubs Archives, the National Archives at College Park, and the Rare and Manuscript Collection at Cornell University provided invaluable guidance. -

The Story of the US Naval Training School (WR) at Hunter College

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Lehman College 1993 Making Waves in the Bronx: The Story of the U.S. Naval Training School (WR) at Hunter College Janet Butler Munch CUNY Lehman College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/le_pubs/195 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] \ 8/:PJ:ORD PARK /3'/(. ·v·o. U.S. NAVAL TRAINING SCHOOL (WR) MAKING WAVES IN THE BRONX: BRONX, NEW YORK 63, N,Y. * THE STORY OF THE U.S. NAVAL t TRAINING SCHOOL .(WR) AT HUNTER COLLEGE Janet Butler Munch Severe manpower shortages, which resulted from fighting a war on two fronts, forced U.S. Navy officials to enlist women in· World War II. Precedent already existed for women serving in the ~ Navy since 11,275 womenl had contributed to the war effort in LJ ::i World War I. Women at that time received no formal indoctrina ~ ~ tion nor was any fom1al organization established. ~ 'q: There was considerable opposition to admitting women into ~ "this man's Navy" during World War II and a Women's Reserve LJ::::=========='J ~ had few champions among the Navy's higher echelons. Congress, WEST /9SYI STREET 0 public interest, and even advocacy from the National Federation Ir========~~IQ of Business and Professional Women's Clubs pressured the Navy ARMORY ..., IN 80llN/J$ ON .SPl:C'JAJ. -

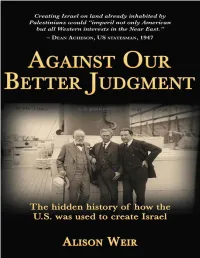

Against Our Better Judgment: the Hidden History of How the U.S. Was

Against Our Better Judgment The hidden history of how the U.S. was used to create Israel ALISON WEIR Copyright © 2014 Alison Weir All rights reserved. DEDICATION To Laila, Sarah, and Peter CONTENTS Aknowledgments Preface Chapter One: How the U.S. “Special Relationship” with Israel came about Chapter Two: The beginnings Chapter Three: Louis Brandeis, Zionism, and the “Parushim” Chapter Four: World War I & the Balfour Declaration Chapter Five: Paris Peace Conference 1919: Zionists defeat calls for self- determination Chapter Six: Forging an “ingathering” of all Jews Chapter Seven: The modern Israel Lobby is born Chapter Eight: Zionist Colonization Efforts in Palestine Chapter Nine: Truman Accedes to Pro-Israel Lobby Chapter Ten: Pro-Israel Pressure on General Assembly Members Chapter Eleven: Massacres and the Conquest of Palestine Chapter Twelve: U.S. front groups for Zionist militarism Chapter Thirteen: Infiltrating displaced person’s camps in Europe to funnel people to Palestine Chapter Fourteen: Palestinian refugees Chapter Fifteen: Zionist influence in the media Chapter Sixteen: Dorothy Thompson, played by Katharine Hepburn & Lauren Bacall Works Cited Further Reading Endnotes ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am extremely grateful to Katy, who plowed through my piles of obscure books and beyond to check it; to Sarah, whose design so enhanced it; to Monica, whose splendid work kept things together; and to the special, encouraging friends (you know who you are) who have made this all possible. Above all, I am profoundly grateful to the authors and editors who have produced superb work on this issue for so many years, many receiving little personal gain despite the excellence and dedication of their labors. -

50 Years of Funding GWI Thanks VGIF for Its Continuing Support

Photo courtesy Louise McLeod courtesyPhoto Louise 1969 - 2019 50 years of Funding GWI thanks VGIF for its continuing support Graduate Women International Chemin du Grand-Montfleury, 48 CH-1290 Versoix, Switzerland Tel: +41 (0) 22 731 23 80 www.graduatewomen.org The Global Impact of VGIF Funding and IFUW / GWI 1969 - 2019 Argentina Finland Nigeria Australia France Pakistan Austria Ghana Philippines Burkina Faso Hungary Russia Burundi India Rwanda Cambodia Ireland Sierra Leone Cameroon Kenya South Africa Canada Korea Sri Lanka Croatia Japan Turkey Egypt Mexico Uganda El Salvador Nepal Vanuatu Estonia Netherlands Zimbabwe Fiji New Zealand GWI thanks VGIF for 50 years of continuing support ©2019 Page 2 VGIF and IFUW / GWI In 1964, the International Federation of University Women (IFUW) held a seminar at Makere University in Kampala, Uganda. Eighteen women representing university women or college graduates from Sub-Sahara Africa joined with seven colleagues from Europe and North and South America to discuss the special needs of women in Africa. They were particularly concerned with the long-range ways and means by which women might achieve a more signifi- cant role in the development of Africa. IFUW members and leaders continued to discuss the role university wom- en might play in providing leadership to identify pressing needs and then do something about these needs not only in Africa but also in Asia and in South America. Their premise was that "if comparatively small sums of money might be available to national or local associations of university women or other women's groups, universities or individuals to undertake imaginative and constructive programs planned by them in their countries or areas; much could be accomplished by broad educational means." 1969 Dr. -

The Roots of the U.S.-Israel Relationship: How the Cold War Tensions Played a Role in U.S

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2013 The Roots of the U.S.-Israel Relationship: How the Cold War Tensions Played a Role in U.S. Foreign Policy in the Middle East Ariel Gomberg Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the History Commons, International Relations Commons, and the Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies Commons Recommended Citation Gomberg, Ariel, "The Roots of the U.S.-Israel Relationship: How the Cold War Tensions Played a Role in U.S. Foreign Policy in the Middle East" (2013). Honors Theses. 670. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/670 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Roots of the U.S.-Israel Relationship: How the Cold War Tensions Played A Role in U.S. Foreign Policy in the Middle East By, Ariel R. Gomberg Senior Thesis Submitted In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in the Department of History UNION COLLEGE June, 2013 Abstract Today the relationship between the United States and Israel includes multiple bi-lateral initiatives in the military, industrial, and private sectors. Israel is Americas most established ally in the Middle East and the two countries are known to possess a “special relationship” highly valued by the United States. Although diplomatic relations between the two countries drive both American and Israeli foreign policy in the Middle East today, following the establishment of the State of Israel the United States originally did not advance major aid and benefits to the new state. -

MINUTES the First Regular Meeting of the University Senate for the Year 1932-33 Was Held in the Library of the Engineering Building, Thursday, October 20, 1932

Year 1932-33 No.1 UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA THE SENATE MINUTES The first regular meeting of the University Senate for the year 1932-33 was held in the Library of the Engineering Building, Thursday, October 20, 1932. Seventy-two members responded to roll call. The following items were presented for consideration by the Committee on Business and Rules and action was taken as indicated. I. THE MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF FEBRUARY 18, 1932 Approved II. SENATE ROSTER FOR 1932-33 Voting List Akerman, John. D. Blitz, Anne D. Alderman, W. H. Boardman, C. W. Allison, John H. Bollman, J. L. (Rochester) Alway, Frederick J. Boss, Andrew Anderson, John E. Boss, William Anderson, William Boyd, Willard L. Appleby, W. R. Boyden, Edward A. Arjona, Carlos Boynton, Ruth E. Arnal, Leon E. Braasch, W. F. (Rochester) Arny, Albert C. Brekhus, Peter J. Bachman, Gustav Brierley, Wilfrid G. Bailey, Clyde H. *Brink, Raymond W. Balfour, D. C. (Rochester) Brooke, William E. Barton, Francis B. Brown, Clara Bass, Frederic H. Brown, Edgar D. Bassett, Louis B. Brueckner, Leo J. Beach, Joseph Bryant, John M. Bell, Elexious T. Buchta, J. W. Benjamin, Harold R. Burkhard, Oscar C. *Berglund, Hilding Burr, George O. tBierman, B. W. Burt, Alfred L. Biester, Alice Burton, S. Chatwood Bieter, Raymond N. Bush, Jol:n N. D. Bird, Charles Bussey, William H. Blakey, Roy G. Butters, Frederic K. Blegen, Theodore Casey, Ralph D. Chapin, F. Stuart French, Robert W. Cherry, Wilbur Garey, L. F. Cheyney, Edward G. Garver, Frederic B. ( Child, Alice M. Geiger, Isaac W. Christensen, Jonas J. Glockler, George Christianson, Peter Goldstein, Harriet Clawson, Benjamin J. -

History of the Commission on the Status of Women1

Short History of the Commission on the Status of Women1 1946: Birth of the Commission on Status of Women United Nations commitments to the advancement of women began with the signing of the UN Charter in San Francisco in 1945. Of the 160 signatories, only four were women - Minerva Bernardino (Dominican Republic), Virginia Gildersleeve (United States), Bertha Lutz (Brazil) and Wu Yi-Fang (China) – but they succeeded in inscribing women’s rights in the founding document of the United Nations, which reaffirms in its preamble “faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity of the human person, in the equal rights of men and women and of Nations large and small”. During the inaugural meetings of the UN General Assembly in London in February 1946, Eleanor Roosevelt, a United States delegate, read an open letter addressed to “the women of the world”: “To this end, we call on the Governments of the world to encourage women everywhere to take a more active part in national and international affairs, and on women who are conscious of their opportunities to come forward and share in the work of peace and reconstruction as they did in war and resistance.” A few days later, a Sub-commission dedicated to the Status of Women was established under the Commission on Human Rights. Many women delegates and representatives of non-governmental organizations believed nevertheless that a separate body specifically dedicated to women’s issues was necessary. The first Chairperson of the Sub- Commission, Bodil Begtrup (Denmark), also requested the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) in May 1946 for a change to full commission status: “Women’s problems have now for the first time in history to be studied internationally as such and to be given the social importance they ought to have. -

Introduction to Radical Teacher's 100Th Issue

RT 100 Anniversary Issue ISSN: 1941-0832 Introduction to Radical Teacher’s 100th Issue by Michael Bennett, Linda Dittmar, and Paul Lauter RT 100 Anniversary Issue RADICAL TEACHER 1 http://radicalteacher.library.pitt.edu No. 100 (Fall 2014) DOI 10.5195/rt.2014.146 o acknowledge and celebrate the 100th issue of goals, or some of them; but the provenance suggested a Radical Teacher, we are reprinting selected kind of sectarianism we wished then, and now, to avoid. essays from our very first issue (December T In the second issue, the subtitle of The Radical 1975) through our last year as a print journal (2012). Teacher was gone. Beginning with the third issue, the Though the selection process was never entirely clear or definite article disappeared. Our first book review, of agreed upon, we have tried to choose articles that reflect Editorial Group member Dick Ohmann’s English in America, Radical Teacher’s focus on class, race, and appeared in issue 3, along with a spirited exchange gender/sexuality, as well as on the socio-economic between the author and other board members concerning contexts of education and educational institutions, audience: the efficacy of reaching out to liberals as primarily but not exclusively in the United States. We also opposed to rallying fellow radicals. A feature called “News wanted some essays that emphasized theory and some for Educational Workers” began with issue 4. Both this that emphasized practice, always hoping that these foci feature and book reviews have been part of the journal came together as praxis. We tried to balance historical ever since. -

Lobbies, Refugees, and Governments| a Study of the Role of the Displaced Persons in the Creation of the State of Israel

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1988 Lobbies, refugees, and governments| A study of the role of the displaced persons in the creation of the state of Israel James Daryl Clowes The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Clowes, James Daryl, "Lobbies, refugees, and governments| A study of the role of the displaced persons in the creation of the state of Israel" (1988). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 2867. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/2867 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 THIS IS AN UNPUBLISHED MANUSCRIPT IN WHICH COPYRIGHT SUBSISTS. ANY FURTHER REPRINTING OF ITS CONTENTS MUST BE APPROVED BY THE AUTHOR, MANSFIELD LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA DATE : 1988 LOBBIES, REFUGEES, and GOVERNMENTS: A Study of the Role of the Displaced Persons in the Creation of the State of Israel By James Daryl Clowes B.A., University of Montana, 1981 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Montana 1988 Approved Chairman, Board of xammers De"Sn, Graduate ScnSol ' '^ x 11 i / •• -C/ 5P Date UMI Number: EP34336 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. -

Dennis Historical Society Newsletter the Untold Story

Dennis Historical Society Newsletter May 2018 Volume 41, No5 Dennis Historical Society – copyright 2018 Internet: www.dennishistoricalsociety.org E-mail: [email protected] Next Board Meeting, Tuesday, May 8th, 2:00 pm, Dennis Memorial Library, 1020 Old Bass River Road Dennis Members Welcome! Please send information & stories for the newsletter to Dave Talbott at the DHS Website email address: [email protected] The Untold Story Code Girls by Liza Mundy is the untold story of the American Women Code Breakers of World War II. Recruited from small Southern towns and posh New England colleges, more than 10,000 American women served in the U.S. Army and Navy as code breakers during World War II. The story of their work, which helped shorten the war and save thousands of lives, has not been told until now. Many of us have watched the PBS television series “The Bletchley Circle” and know of the wartime code breaking efforts in England. Now thanks to our own Bob Poskitt, we will learn about such efforts in the United States, and a connection to our Society! Two women quoted in the book are Elizabeth Reynard and her cousin, Virginia Gildersleeve, ladies very important in the founding of the Dennis Historical Society. Elizabeth was a retired Barnard College professor when she purchased the Captain Theophilus Baker House and Buildings at the corner of Main Street and Trotting Park Road in South Dennis in the 1950s. She named the house “Jericho” after the city in the Bible whose “walls were falling down.” Following her death in January 1962, the restoration of the house and grounds was continued by Virginia Gildersleeve, Dean Emeritus of Barnard, who then gifted the property to the Town of Dennis in 1962. -

Dzvinka Stefanyshyn Professor Jacoby Annie Nathan Meyer and Barnard College’S Exclusivity

Dzvinka Stefanyshyn Professor Jacoby Annie Nathan Meyer and Barnard College’s Exclusivity Since its founding years, Columbia University has always been a center of wealth and intellect in the city of New York. In 1774, its founders had wanted to establish an institution that was exclusive to wealthy white males, yet be a pillar of one of the most influential colleges in the world. Illuminating this sense of exclusion, the university made it no secret that it would not allow women nor Blacks to enter its gates as students. These exclusions, however, were not unique to Columbia University. It was merely a reflection of the kind of society that individuals lived in at the time – beginning with ideals of white supremacism in the Colonial period that extended out into the early twentieth century. As the nation was evolving, breaking free from British rule, some groups such as women sought change in the education system. Yet, even with the founding of women’s colleges that began to take root in the northeastern states, New York City was lacking such an institution. Today, there are several prominent women’s colleges in the United States, which are called the Seven Sisters. The first of the Seven Sisters was Mount Holyoke, founded in 1837 by Mary Lyon. It first served as a female seminary that was meant to promote higher education amongst women during the first half of the 19th century. Mount Holyoke Female Seminary was initially chartered as a teaching seminary in 1836, but with the institution officially became a College after fundraising from the Trustees and introduction of entrance exams.